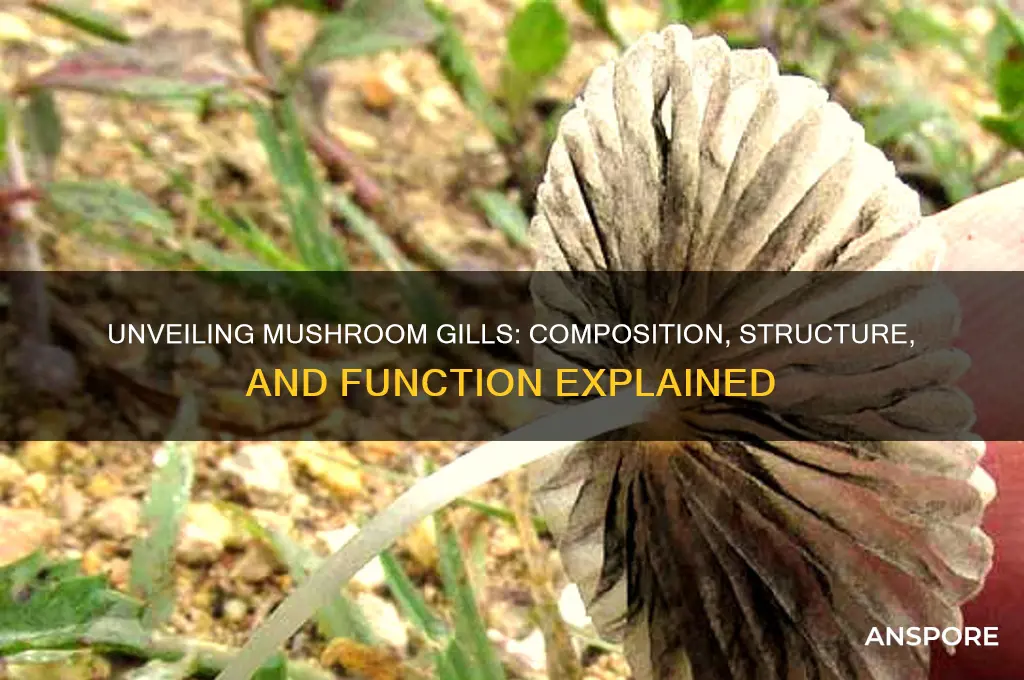

Mushroom gills, also known as lamellae, are the thin, blade-like structures found on the underside of the cap in many mushroom species. These delicate structures play a crucial role in spore production and dispersal. Gills are typically made up of densely packed, microscopic cells that form a thin layer of tissue. This tissue is primarily composed of hyphae, which are filamentous structures characteristic of fungi. The hyphae in the gills are often arranged in a parallel fashion, creating a smooth surface for spore development. Additionally, the gills may contain specialized cells called basidia, which are responsible for producing and releasing spores, ensuring the mushroom's reproductive success. The composition of gills can vary slightly between different mushroom species, but their primary function remains consistent across the fungal kingdom.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Composition | Primarily composed of tightly packed hyphae, which are filamentous structures of fungal cells. |

| Function | Serve as the primary site for spore production and dispersal in most mushroom species. |

| Structure | Thin, blade-like structures radiating from the mushroom's stem, attached to the cap (pileus). |

| Spore Formation | Spores are produced on the surface of the gills, specifically on structures called basidia. |

| Color | Color varies by species, often used for identification (e.g., white, pink, brown, black). |

| Attachment | Gills can be free, attached, notched, or decurrent, depending on how they connect to the stem. |

| Density | Gill spacing (distant, close, or crowded) is a key taxonomic feature. |

| Edge | The gill edge may have specific features like sterigmata or cystidia, aiding in identification. |

| Texture | Can be smooth, waxy, or powdery, depending on the species. |

| Lifespan | Temporary structures that degrade after spore release. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Cellular Structure: Gills consist of densely packed hyphae, the mushroom's filamentous cells

- Spore Production: Gills are the primary site for spore formation and dispersal

- Tissue Composition: Made of soft, thin-walled cells with high moisture content

- Color Variations: Gill color ranges from white to black, aiding species identification

- Attachment Types: Gills attach to the stem in various ways (free, adnate, decurrent)

Cellular Structure: Gills consist of densely packed hyphae, the mushroom's filamentous cells

The gills of a mushroom are a marvel of fungal anatomy, serving as the primary site for spore production and dispersal. At the heart of their structure lies a complex network of hyphae, the filamentous cells that are the building blocks of fungal organisms. These hyphae are densely packed within the gill tissue, forming a highly organized and functional system. Each hypha is a long, slender tube-like structure, typically divided into compartments by cross-walls called septa, though some fungi have continuous, non-septate hyphae. This dense arrangement of hyphae provides the structural integrity and surface area necessary for the gills to perform their reproductive role efficiently.

The cellular structure of mushroom gills is optimized for spore development and release. The hyphae within the gills are not merely stacked but are intricately arranged to form a hymenium, the spore-bearing layer. This layer is where the basidia, specialized club-shaped cells, develop. Each basidium produces spores, which are then released into the environment. The dense packing of hyphae ensures that the hymenium is both robust and maximally exposed, facilitating the efficient dispersal of spores. This arrangement is critical for the mushroom's life cycle, as it relies on spores to colonize new substrates and propagate the species.

The filamentous nature of hyphae allows them to interweave and create a cohesive yet porous structure within the gills. This porosity is essential for gas exchange, enabling the gills to respire and support the metabolic processes required for spore production. Additionally, the hyphae's ability to grow and branch extensively contributes to the gill's flexibility and resilience, allowing it to maintain its shape despite environmental stresses. The dense packing of these filamentous cells also enhances the gill's surface area, further increasing its efficiency in spore dispersal.

Microscopic examination of gill tissue reveals the remarkable uniformity and precision of hyphal arrangement. The hyphae are not randomly distributed but are aligned in a manner that maximizes their functional role. This alignment is maintained by the rigid cell walls of the hyphae, composed primarily of chitin, a tough polysaccharide that provides structural support. The chitinous walls also protect the hyphae from mechanical damage and desiccation, ensuring the longevity and functionality of the gills. Thus, the cellular structure of the gills is a testament to the adaptability and efficiency of fungal biology.

In summary, the gills of a mushroom are composed of densely packed hyphae, the filamentous cells that form the backbone of fungal anatomy. This arrangement is not arbitrary but is finely tuned to support spore production and dispersal. The hyphae's structure, with their chitinous walls and compartmentalized interiors, provides both strength and flexibility, while their dense packing maximizes surface area and functionality. Understanding this cellular structure offers insights into the ingenious ways fungi have evolved to thrive and reproduce in diverse environments.

Mushrooms: Are They Vegetables or Something Else?

You may want to see also

Spore Production: Gills are the primary site for spore formation and dispersal

The gills of a mushroom, often referred to as lamellae, are a crucial component of the fungus's reproductive system. These thin, blade-like structures are typically found radiating from the stem and attached to the underside of the cap. Gills are primarily composed of densely packed hyphae, which are filamentous cells that make up the body of the fungus. This intricate network of hyphae forms a highly efficient surface area for the critical process of spore production.

Spore production is a fundamental aspect of a mushroom's life cycle, and the gills play a central role in this process. As the primary site for spore formation, the gills are where the magic of reproduction happens. The hyphae within the gills develop specialized cells called basidia, which are the spore-bearing structures. Each basidium typically produces four spores, and these spores are the means by which mushrooms reproduce and disperse. The basidia are often club-shaped and are attached to the hyphae, forming a fertile layer on the gill's surface.

The process of spore formation is a delicate and intricate one. Within the basidium, the genetic material is replicated, and through a process called meiosis, spores are produced. These spores are haploid, containing half the number of chromosomes, and are genetically unique. As the spores mature, they are released from the basidium, often with the help of a small drop of liquid that forms at the tip of the basidium, propelling the spores forward. This mechanism ensures that spores are dispersed effectively.

Dispersal is a critical phase in the life of a mushroom, and the gills are strategically designed to facilitate this. The arrangement of gills provides an extensive surface area, allowing for the production of millions of spores. When mature, these spores are released into the air, often in response to environmental triggers such as changes in humidity or air currents. The spores are lightweight and can be carried over long distances, ensuring the mushroom's genetic material can reach new habitats. This dispersal mechanism is vital for the survival and propagation of mushroom species.

The structure of the gills is optimized for efficient spore release. The spacing and arrangement of gills allow for optimal air circulation, aiding in spore dispersal. Some mushrooms even have gills with a waxy or slimy coating, which helps spores slide off more easily. This adaptation ensures that spores are not trapped and can be carried away by the slightest breeze, increasing the chances of successful colonization in new environments. Thus, the gills' role in spore production and dispersal is a fascinating example of nature's ingenuity in fungal reproduction.

Shiitake Mushrooms: Are They Safe or Toxic?

You may want to see also

Tissue Composition: Made of soft, thin-walled cells with high moisture content

The gills of a mushroom, often referred to as lamellae, are a critical component of the fungus's reproductive system. When examining their tissue composition, it becomes evident that these structures are primarily composed of soft, thin-walled cells that contribute to their delicate yet functional nature. These cells, known as hyphae, are the building blocks of fungal tissues and are characterized by their thin cell walls, which are typically made of chitin, a lightweight yet sturdy polysaccharide. This composition allows the gills to maintain structural integrity while remaining flexible, a feature essential for their role in spore production and dispersal.

The high moisture content within these thin-walled cells is another defining aspect of gill tissue composition. This moisture is crucial for maintaining the softness and pliability of the gills, enabling them to support the development and release of spores effectively. The water content also facilitates nutrient transport within the hyphae, ensuring that the gills remain metabolically active during the reproductive phase of the mushroom. This high moisture level is a result of the gills' exposure to the environment, which allows them to absorb and retain water efficiently.

In addition to their soft texture and high moisture content, the thin-walled cells of mushroom gills are highly specialized for their function. These cells are often densely packed with organelles such as mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum, which support the energy-intensive process of spore formation. The thin walls of these cells also minimize diffusion distances, allowing for rapid exchange of gases and nutrients, which is vital for the gills' metabolic processes. This specialization ensures that the gills can perform their reproductive role with maximum efficiency.

The softness of the gill tissue is not merely a passive trait but is actively maintained by the mushroom. The thin-walled cells are constantly hydrated, which prevents them from becoming rigid or brittle. This softness is particularly important during the maturation of spores, as it allows the gills to bend and flex in response to environmental conditions, such as air currents, which aid in spore dispersal. Without this softness, the gills would be less effective in their primary function of releasing spores into the surrounding environment.

Finally, the tissue composition of mushroom gills, characterized by soft, thin-walled cells with high moisture content, reflects a balance between structural support and functional adaptability. The chitinous cell walls provide enough strength to hold the gills in place, while their thinness and moisture content ensure that they remain supple and responsive. This unique composition is a testament to the evolutionary ingenuity of fungi, allowing mushrooms to thrive in diverse ecosystems by efficiently reproducing through their gills. Understanding this tissue composition not only sheds light on the biology of mushrooms but also highlights the intricate relationship between structure and function in the natural world.

Mushrooms Grown on Wheat Substrate: Are They Gluten-Free?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$13.99 $17.99

Color Variations: Gill color ranges from white to black, aiding species identification

The gills of a mushroom, also known as lamellae, are a crucial part of the fungus's structure, primarily composed of tightly packed, thin, blade-like structures that radiate outward from the stem. These gills are made up of fungal tissue, specifically hyphae, which are filamentous cells that form the body of the mushroom. The hyphae in the gills are arranged in a way that maximizes surface area, facilitating the release and dispersal of spores, which are essential for the mushroom's reproduction. When discussing color variations, it’s important to note that gill color is a key characteristic used in identifying mushroom species. Ranging from white to black, with numerous shades in between, gill color can provide valuable clues about the mushroom's identity, toxicity, and habitat.

Gill color is influenced by various factors, including the mushroom's maturity, environmental conditions, and the pigments present in the fungal tissue. For instance, young mushrooms often have lighter-colored gills that darken as the spores mature. White gills are common in many edible species, such as the button mushroom (*Agaricus bisporus*), while darker shades like brown, gray, or black are often seen in species like the shiitake (*Lentinula edodes*) or the deadly destroying angel (*Amanita bisporigera*). The transition from white to black, and the specific hues in between, can be a diagnostic feature for mycologists and foragers alike. For example, gills that start pink and turn brown as spores mature are characteristic of the genus *Cortinarius*, while bright yellow gills may indicate the presence of a *Chanterelle*.

Intermediate colors, such as cream, tan, or olive, are also significant in species identification. These shades often result from the accumulation of specific pigments, such as melanins or carotenoids, in the gill tissue. Melanins, for instance, are responsible for darker colors and are often associated with mushrooms that grow in decaying wood or soil. Carotenoids, on the other hand, produce yellow, orange, or reddish hues and are found in species like the *Lactarius* genus. Understanding these pigmentations and their role in gill coloration can help distinguish between similar-looking species and avoid potentially toxic look-alikes.

The range of gill colors from white to black is not just a visual trait but also a functional adaptation. Darker gills, for example, may absorb more heat, aiding in spore dispersal in cooler environments. Conversely, lighter gills might reflect sunlight, preventing overheating in warmer habitats. This diversity in color also reflects the mushroom's evolutionary history and ecological niche, making gill color a multifaceted characteristic in mycology. For foragers and researchers, documenting gill color accurately—including its initial shade, changes over time, and any patterns or spots—is essential for precise identification and safe consumption.

In summary, the color variations of mushroom gills, spanning from white to black, are a critical tool for species identification. These colors are determined by the mushroom's biology, environment, and developmental stage, with each shade or hue offering insights into the fungus's taxonomy and ecology. By carefully observing and recording gill color, enthusiasts and experts can better navigate the complex world of mushrooms, ensuring both scientific accuracy and safety in foraging practices.

Ketamine and Mushrooms: A Psychedelic Mix

You may want to see also

Attachment Types: Gills attach to the stem in various ways (free, adnate, decurrent)

The gills of a mushroom, also known as lamellae, are a crucial part of the fungus's structure, primarily serving as the site for spore production and dispersal. These delicate, sheet-like structures are typically found radiating outward from the stem (or stipe) beneath the cap (or pileus) of the mushroom. The gills are composed of densely packed hyphae, which are filamentous cells that make up the body of the fungus. These hyphae are often covered in basidia, the specialized spore-bearing cells that give gills their primary function in reproduction. Understanding how gills attach to the stem is essential for mushroom identification, as this characteristic varies significantly among species.

One common attachment type is free gills, where the gills are not attached to the stem at all. In this case, the gills appear to end abruptly without touching the stipe, leaving a clear space between the gill edge and the stem. This type of attachment is often observed in mushrooms of the genus *Agaricus*, such as the common button mushroom. Free gills are relatively easy to identify due to their distinct separation from the stem, making them a key feature for mycologists and foragers alike.

Another attachment type is adnate gills, where the gills are broadly attached to the stem along their entire depth. This creates a strong, seamless connection between the gill and the stipe, giving the mushroom a more robust appearance. Adnate gills are commonly found in species like the *Boletus* genus, where the gills are often closely packed and firmly anchored to the stem. This attachment style can vary in strength, with some gills appearing slightly curved or notched where they meet the stem, but they remain firmly connected.

Decurrent gills represent a third attachment type, where the gills extend downward along the stem, often in a ridge-like or forked manner. This creates a distinctive appearance, as the gills seem to run down the stipe rather than stopping at the base of the cap. Decurrent gills are characteristic of mushrooms in the genus *Pleurotus*, such as the oyster mushroom, where this feature is highly pronounced. The extent of decurrence can vary, from a slight extension to a significant run-down, but it is always a defining feature for identification.

Lastly, some mushrooms exhibit notched or sinuate gills, which are variations of the adnate type. In these cases, the gills are attached to the stem but have a wavy or indented edge where they meet the stipe. This creates a less uniform attachment compared to adnate gills, adding another layer of complexity to mushroom identification. Understanding these attachment types—free, adnate, decurrent, and their variations—is vital for accurately classifying mushrooms and appreciating the diversity of fungal structures in nature. Each attachment style not only aids in identification but also reflects the evolutionary adaptations of mushrooms to their environments.

Mushroom Coffee: Safe Super Drink or Fad?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The gills of a mushroom are made of thin, closely spaced, blade-like structures composed of fungal tissue.

Yes, mushroom gills contain specialized cells called basidia, which produce and release spores for reproduction.

In most edible mushrooms, the gills are safe to eat and are part of the mushroom’s fruiting body, though some species may have gills that are bitter or unpalatable.

The primary function of mushroom gills is to produce and disperse spores, which are essential for the mushroom’s reproduction and propagation.

Not all mushrooms have gills; some have pores, spines, or other structures for spore production, depending on the species and family.