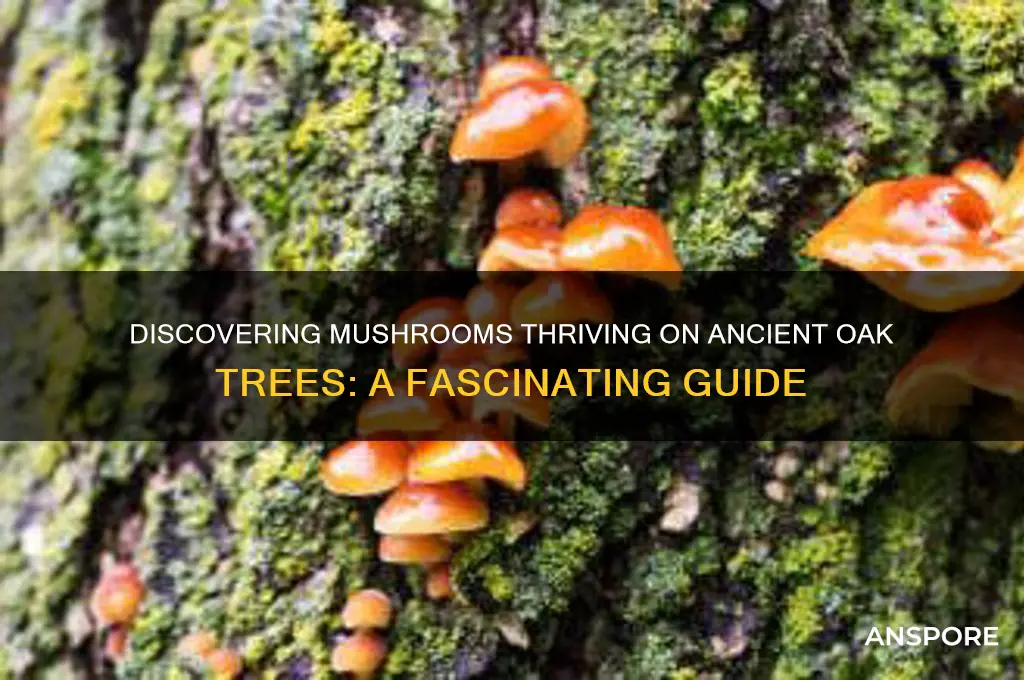

Mushrooms that grow on old oak trees, often referred to as lignicolous or wood-dwelling fungi, are a fascinating group of organisms that play a crucial role in forest ecosystems. These fungi, which include species like the iconic oak bracket (*Inonotus dryadeus*) and the turkey tail (*Trametes versicolor*), thrive on decaying wood, breaking down the tough lignin and cellulose in oak trees as part of the natural decomposition process. Their presence not only signifies the tree’s advanced age and the progression of its life cycle but also highlights the intricate relationship between fungi and their woody hosts. Beyond their ecological importance, these mushrooms are often prized for their unique textures, colors, and, in some cases, medicinal properties, making them a subject of interest for both mycologists and nature enthusiasts alike.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Types of Oak-Loving Mushrooms: Identify common fungi species that thrive on aging oak trees

- Symbiotic Relationships: Explore how mushrooms and oaks mutually benefit in their ecosystem

- Edible vs. Toxic Varieties: Learn which oak tree mushrooms are safe to consume and which are harmful

- Environmental Factors: Understand how climate and soil conditions influence mushroom growth on oaks

- Conservation Efforts: Discover initiatives to protect oak trees and their associated fungal communities

Types of Oak-Loving Mushrooms: Identify common fungi species that thrive on aging oak trees

Oak trees, particularly aging ones, provide a unique and nutrient-rich environment for various fungi species to thrive. These mushrooms often form symbiotic relationships with the trees, breaking down decaying wood and recycling nutrients back into the ecosystem. Identifying the types of mushrooms that grow on old oak trees can be both fascinating and educational. Here are some common fungi species that are frequently found in such habitats.

One of the most recognizable oak-loving mushrooms is the Oyster Mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*). This fungus is not only a favorite among foragers for its culinary uses but also plays a crucial role in decomposing hardwood, including oak. Oyster mushrooms have a distinctive fan-like or shell-shaped cap, ranging in color from light gray to brown. They typically grow in clusters on the bark or exposed wood of aging or dead oak trees. Their ability to break down lignin and cellulose makes them essential in the natural recycling process of forest ecosystems.

Another common species is the Turkey Tail (*Trametes versicolor*). This bracket fungus is known for its striking, banded colors resembling the tail feathers of a turkey. Turkey Tail grows in tiered, fan-shaped formations on oak and other hardwoods. While not typically consumed due to its tough texture, it is highly valued for its medicinal properties, particularly in boosting immune function. Its presence on old oak trees indicates advanced wood decay, as it primarily colonizes dead or dying timber.

The Lion's Mane Mushroom (*Hericium erinaceus*) is a unique and visually striking fungus often found on oak trees. Resembling a cascading clump of icicles or a lion's mane, this mushroom has long, dangling spines instead of gills. It is highly sought after for its culinary and medicinal benefits, including potential neuroprotective properties. Lion's Mane typically grows on mature or decaying oak trees, where it plays a role in breaking down the wood while providing a food source for foragers.

For those interested in identifying mushrooms on old oak trees, the Artist's Conk (*Ganoderma applanatum*) is another notable species. This bracket fungus forms large, brown, shelf-like structures on the trunks of aging oaks. Its name derives from its unique ability to create spore prints when the underside is placed on paper, resembling artistic patterns. While not edible due to its woody texture, Artist's Conk is a sign of significant wood decay and adds to the biodiversity of oak tree ecosystems.

Lastly, the Chicken of the Woods (*Laetiporus sulphureus*) is a vibrant and edible mushroom that frequently grows on oak trees. Its bright orange-yellow, shelf-like clusters are hard to miss and often appear on wounded or decaying oaks. This fungus is a saprophyte, feeding on dead wood and accelerating the decomposition process. Foragers prize it for its chicken-like texture and flavor when cooked, though proper identification is crucial to avoid toxic look-alikes.

Understanding and identifying these oak-loving mushrooms not only enhances your knowledge of forest ecosystems but also highlights the intricate relationships between fungi and aging oak trees. Each species plays a unique role in nutrient cycling and decomposition, contributing to the health and sustainability of woodland environments.

Is Growing Mushrooms at Home Safe or Risky?

You may want to see also

Symbiotic Relationships: Explore how mushrooms and oaks mutually benefit in their ecosystem

In the intricate web of forest ecosystems, the relationship between mushrooms and old oak trees exemplifies a profound symbiotic bond. One of the most common mushrooms found on old oaks is the oak bracket fungus (*Inonotus dryadeus*), which forms distinctive shelf-like structures on decaying wood. These fungi play a crucial role in nutrient cycling by breaking down complex organic matter in the tree, such as lignin and cellulose, into simpler compounds. This process not only aids in the decomposition of dead or dying oak tissue but also releases essential nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus back into the soil, enriching it for the oak and other surrounding plants.

The symbiotic relationship extends beyond decomposition, as mycorrhizal fungi, such as those in the genus *Amanita* or *Boletus*, form a mutualistic partnership with oak roots. These fungi colonize the roots of the oak tree, creating a vast underground network known as the "wood wide web." Through this network, the fungi enhance the oak's ability to absorb water and nutrients, particularly in nutrient-poor soils. In return, the oak tree provides the fungi with carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis, which the fungi cannot synthesize on their own. This exchange ensures the health and resilience of both organisms, especially in challenging environmental conditions.

Mushrooms growing on old oak trees also contribute to the overall biodiversity of the ecosystem. As decomposers, they create microhabitats for insects, bacteria, and other microorganisms, fostering a thriving soil community. This biodiversity, in turn, supports the oak tree by improving soil structure and fertility. Additionally, the presence of mushrooms can indicate a healthy, mature oak forest, as these fungi often thrive in stable, undisturbed environments. Their fruiting bodies also serve as a food source for wildlife, further integrating them into the food web.

The relationship between mushrooms and oaks highlights the concept of ecosystem engineers, where both organisms modify their environment to mutual advantage. For instance, by breaking down dead wood, mushrooms prevent the accumulation of debris, reducing the risk of pests and diseases that could harm the oak. Simultaneously, the oak provides a stable substrate for the mushrooms to grow, ensuring their survival and reproduction. This interdependence underscores the delicate balance of forest ecosystems and the importance of preserving old-growth trees like oaks, which serve as critical habitats for these fungi.

Lastly, the symbiotic relationship between mushrooms and oaks has broader ecological implications, particularly in carbon sequestration. As mushrooms decompose oak wood, they release carbon dioxide, but they also store carbon in their mycelial networks and the soil. This process contributes to the forest's ability to act as a carbon sink, mitigating climate change. Thus, protecting these symbiotic relationships is not only vital for the health of individual oaks and their associated fungi but also for the sustainability of the entire ecosystem. Understanding and conserving these partnerships is essential for maintaining the biodiversity and resilience of forest habitats.

Do Turkey Tail Mushrooms Thrive on Pine Trees? Exploring Growth Habits

You may want to see also

Edible vs. Toxic Varieties: Learn which oak tree mushrooms are safe to consume and which are harmful

Oak trees, particularly old ones, are often hosts to a variety of mushrooms, some of which are edible and prized by foragers, while others are toxic and pose serious health risks. Understanding the difference between these varieties is crucial for anyone interested in mushroom hunting. One of the most well-known edible mushrooms that grow on oak trees is the Lion's Mane mushroom (*Hericium erinaceus*). This distinctive fungus, with its cascading white spines, is not only safe to eat but also highly regarded for its culinary and medicinal properties. It is rich in antioxidants and has been studied for its potential neuroprotective effects. When foraging for Lion's Mane, look for its unique appearance and ensure it is growing on a hardwood tree like oak.

In contrast, Oak Bracket (*Bipolaris maydis*) is a toxic mushroom commonly found on old oak trees. This fungus forms hard, woody brackets that are brown to black in color and can be easily mistaken for other bracket fungi. Ingesting Oak Bracket can lead to severe gastrointestinal distress and, in some cases, liver damage. It is essential to avoid consuming any bracket fungi unless you are absolutely certain of their identification, as many species in this group are toxic. Another toxic variety to watch out for is the Jack-O-Lantern mushroom (*Omphalotus olearius*), which grows in clusters on decaying oak wood. Its bright orange to yellow gills and bioluminescent properties make it visually striking, but it is highly poisonous, causing severe cramps, vomiting, and dehydration.

On the edible side, Oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) are another variety that often grows on oak trees. These mushrooms are easily recognizable by their fan-like caps and creamy white to grayish color. They are not only safe to eat but also delicious, with a mild, anise-like flavor that pairs well with various dishes. Oyster mushrooms are also rich in protein and vitamins, making them a nutritious addition to any meal. However, it is important to distinguish them from the False Oyster (*Phyllogaster brasiliensis*), a toxic look-alike that can cause digestive issues.

Foraging for mushrooms on oak trees requires careful identification and caution. One particularly dangerous toxic variety is the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*), which can sometimes be found near oak trees. This mushroom resembles certain edible species, such as the Paddy Straw mushroom, but is deadly poisonous. It contains amatoxins that can cause severe liver and kidney damage, often leading to death if consumed. Always cross-check multiple identifying features, such as the presence of a cup-like volva at the base and a ring on the stem, to avoid this lethal fungus.

In summary, while oak trees host a variety of mushrooms, it is essential to differentiate between edible and toxic species. Edible varieties like Lion's Mane and Oyster mushrooms offer culinary and health benefits, but toxic species such as Oak Bracket, Jack-O-Lantern, False Oyster, and Death Cap pose significant risks. Always consult a reliable field guide or an experienced forager, and never consume a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identification. Safe foraging practices ensure that you can enjoy the bounty of oak tree mushrooms without endangering your health.

Can Oyster Mushrooms Thrive on Maple Trees? Exploring the Possibility

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Factors: Understand how climate and soil conditions influence mushroom growth on oaks

Mushrooms that grow on old oak trees, often referred to as oak-associated fungi, are significantly influenced by environmental factors, particularly climate and soil conditions. Climate plays a pivotal role in determining the presence and abundance of these mushrooms. Oak-loving species such as the Lion's Mane (*Hericium erinaceus*), Chicken of the Woods (*Laetiporus sulphureus*), and Oak Bracket (*Piptoporus betulinus*) thrive in temperate climates with distinct seasonal changes. These fungi require moderate temperatures, typically ranging between 50°F and 70°F (10°C and 21°C), for optimal growth. Extreme heat or cold can inhibit their development, as many of these species are adapted to the cooler, humid conditions found in deciduous forests where oaks dominate.

Humidity and rainfall are critical climatic factors for mushroom growth on oaks. Most oak-associated fungi are saprotrophic or parasitic, relying on moisture to decompose wood or penetrate tree tissues. Adequate rainfall ensures the substrate (the oak tree) remains damp, facilitating spore germination and mycelial growth. Prolonged droughts can stress the fungi, reducing their ability to colonize and fruit. Conversely, excessive rain can lead to waterlogged soil, depriving the mycelium of oxygen and hindering growth. Therefore, a balanced precipitation pattern is essential for these mushrooms to flourish.

Soil conditions are equally important, as they directly impact the health of the oak tree and, consequently, the fungi that depend on it. Oak trees prefer well-drained, slightly acidic soils with a pH range of 5.0 to 6.5. Mushrooms growing on oaks benefit from these soil conditions, as they often rely on the tree's nutrients. Soil rich in organic matter supports a robust mycorrhizal network, which can indirectly benefit saprotrophic fungi by improving overall tree health. Poor soil drainage or extreme alkalinity can weaken the oak, making it less hospitable for fungi. Additionally, soil compaction can restrict root growth, reducing the tree's ability to uptake water and nutrients, which in turn affects fungal growth.

Light exposure and microclimate variations around the oak tree also influence mushroom development. Many oak-associated fungi prefer shaded environments, as direct sunlight can desiccate delicate fruiting bodies. The microclimate created by the oak's canopy provides the necessary shade and humidity for mushrooms to thrive. Furthermore, the direction of the slope and the tree's position in the landscape can affect moisture retention and temperature, creating localized conditions favorable for specific fungal species. For instance, north-facing slopes in the Northern Hemisphere tend to be cooler and moister, benefiting fungi that require such conditions.

Seasonal changes and their interaction with climate and soil factors are crucial for the life cycle of oak-associated mushrooms. Most of these fungi fruit in late summer to fall, coinciding with cooler temperatures and increased humidity. This timing aligns with the oak tree's physiological processes, such as nutrient redistribution and leaf drop, which can influence fungal activity. Understanding these seasonal patterns helps predict when and where mushrooms are likely to appear on old oak trees. By considering these environmental factors, enthusiasts and researchers can better appreciate the intricate relationship between climate, soil, and mushroom growth on oaks.

Reviving Roots: A Guide to Growing Back-to-the-Roots Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Conservation Efforts: Discover initiatives to protect oak trees and their associated fungal communities

Oak trees, particularly old-growth specimens, are vital ecosystems that support a diverse array of fungal communities, including mushrooms like the oak bracket (*Bipolaris maydis*), beefsteak fungus (*Fistulina hepatica*), and various mycorrhizal species. These fungi play crucial roles in nutrient cycling, tree health, and biodiversity. However, habitat loss, climate change, and invasive species threaten both oak trees and their associated fungi, necessitating targeted conservation efforts. Below are key initiatives aimed at protecting these interconnected ecosystems.

Habitat Preservation and Restoration

One of the most effective conservation strategies is the preservation and restoration of oak woodlands and forests. Organizations like the Woodland Trust and The Nature Conservancy focus on protecting old-growth oak habitats, which are critical for both tree longevity and fungal diversity. These efforts include establishing protected areas, reforestation projects using native oak species, and managing land to mimic natural processes, such as controlled burns to reduce invasive species and promote oak regeneration. Preserving dead and decaying wood is also essential, as it provides substrate for saprotrophic fungi that decompose organic matter and recycle nutrients.

Fungal Conservation Programs

Specific initiatives targeting fungal communities are gaining traction. The Society for the Protection of Underground Networks (SPUN) and similar groups are mapping mycorrhizal networks, which are vital for oak health, as these fungi form symbiotic relationships with tree roots, enhancing nutrient uptake and resilience to stressors. Additionally, citizen science programs, such as the Fungal Diversity Survey, encourage public participation in documenting fungal species associated with oaks, providing valuable data for conservation planning. Efforts to cultivate and reintroduce endangered fungal species, particularly those with mutualistic relationships with oaks, are also underway in controlled environments.

Sustainable Forestry Practices

Adopting sustainable forestry practices is critical to safeguarding oak trees and their fungal partners. This includes selective logging to minimize habitat disruption, retaining veteran trees that host diverse fungal communities, and avoiding the use of fungicides that could harm beneficial fungi. Certification programs like the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) promote responsible forest management, ensuring that oak habitats are maintained while supporting local economies. Educating landowners and foresters about the ecological importance of fungi in oak ecosystems is a key component of these initiatives.

Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation

Climate change poses significant threats to oak trees and their fungal communities, from altered precipitation patterns to increased pest outbreaks. Conservation efforts include planting oak species resilient to changing conditions and restoring wetlands and riparian zones to enhance ecosystem resilience. Research into how fungal communities respond to climate stressors is also underway, with studies focusing on heat-tolerant mycorrhizal species that could support oak survival in warmer climates. Policy advocacy for reducing greenhouse gas emissions complements these on-the-ground efforts.

Public Awareness and Education

Raising awareness about the ecological significance of oak trees and their fungi is essential for garnering support for conservation initiatives. Educational campaigns, nature walks, and workshops highlight the roles of mushrooms in forest health and the cultural value of oaks. Schools and community groups are increasingly involved in tree-planting events and fungal monitoring projects, fostering a sense of stewardship. By engaging the public, conservationists aim to ensure long-term protection for these vital ecosystems.

In summary, protecting oak trees and their associated fungal communities requires a multifaceted approach, combining habitat preservation, fungal-specific conservation, sustainable practices, climate adaptation, and public engagement. These initiatives not only safeguard biodiversity but also maintain the ecological services provided by oak-fungal ecosystems, ensuring their survival for future generations.

Cow Manure for Mushroom Cultivation: Benefits, Risks, and Best Practices

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mushrooms like the Oak Polypore (*Piptoporus quercinus*), Turkey Tail (*Trametes versicolor*), and Lion's Mane (*Hericium erinaceus*) are frequently found on old oak trees.

Not all mushrooms on oak trees are edible. Some, like Lion's Mane, are safe and prized for culinary use, while others, such as certain polypores, are inedible or toxic. Always identify mushrooms accurately before consuming.

Mushrooms grow on old oak trees because the decaying wood provides a nutrient-rich substrate for fungal growth. These fungi play a role in decomposing the tree, returning nutrients to the ecosystem.