Mushroom spines, often referred to as spines or teeth, are unique structures found on certain species of fungi, particularly in the Hydnum and Hydnellum genera. Unlike the gills or pores commonly seen in mushrooms, these spines are tooth-like projections that line the underside of the cap, serving as the primary site for spore production. Their distinctive appearance not only aids in species identification but also plays a crucial role in the mushroom's ecological function, facilitating spore dispersal and nutrient absorption. Understanding the structure and purpose of these spines provides valuable insights into the diversity and adaptability of fungal life.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

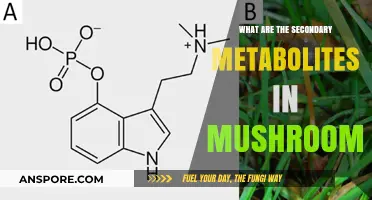

| Definition | Spines, also known as teeth or acanthophyses, are the downward-extending, sharp or pointed structures found on the underside (hymenium) of certain mushroom species, particularly in the Hydnoid and Hydnum genera. |

| Function | Primarily serve as spore-bearing structures, replacing the typical gills or pores found in other mushrooms. |

| Structure | Can vary in shape (e.g., sharp, blunt, forked) and size, depending on the species. |

| Species | Commonly found in mushrooms like Hydnum repandum (Hedgehog mushroom), Hydnellum peckii (Bleeding Tooth fungus), and other Hydnoid fungi. |

| Spore Release | Spores are produced on the surface of the spines and released into the air as the mushroom matures. |

| Texture | Spines can feel brittle, flexible, or rigid, depending on the species and maturity. |

| Color | Ranges from white, cream, yellow, to brown, and even reddish in some species like Hydnellum peckii. |

| Ecological Role | Aid in spore dispersal, contributing to the mushroom's reproductive cycle and ecosystem role as decomposers or mycorrhizal partners. |

| Edibility | Some spine-bearing mushrooms, like Hydnum repandum, are edible and prized for their unique texture and flavor. Others may be inedible or toxic. |

| Identification Key | Presence of spines is a critical feature for identifying Hydnoid fungi, distinguishing them from gilled or pored mushrooms. |

Explore related products

$43.5 $65.95

What You'll Learn

- Types of Mushroom Spines: Different mushrooms have unique spine structures, varying in shape, size, and arrangement

- Function of Spines: Spines aid in spore dispersal, protection, and environmental adaptation in mushroom species

- Spine Formation Process: Spines develop from specialized cells called basidia during mushroom maturation

- Spines in Identification: Spines are key features for classifying and identifying mushroom species accurately

- Ecological Role of Spines: Spines interact with insects and microorganisms, influencing mushroom ecology and survival

Types of Mushroom Spines: Different mushrooms have unique spine structures, varying in shape, size, and arrangement

Mushroom spines, often referred to as "spines" or "teeth," are a distinctive feature found on the underside of certain mushroom caps, replacing the more common gills or pores. These structures are responsible for spore production and dispersal, playing a crucial role in the mushroom's life cycle. The spines can vary widely across different mushroom species, with unique characteristics in shape, size, and arrangement. For instance, some mushrooms have long, slender spines, while others feature short, stubby ones. Understanding these variations is essential for accurate mushroom identification and classification.

One notable type of mushroom spine is found in the genus Hydnum, commonly known as hedgehog mushrooms. These mushrooms have spines that are typically thick, rigid, and closely packed, resembling the quills of a hedgehog. The spines in *Hydnum repandum*, for example, are relatively broad and fork near the base, giving them a distinctive appearance. In contrast, *Hydnellum* species often have finer, more delicate spines that can be brittle to the touch. The arrangement of these spines is usually even and uniform, covering the entire underside of the cap, which aids in efficient spore release.

Another group of mushrooms with unique spine structures is the Hericium genus, often called lion's mane or pom-pom mushrooms. These mushrooms have long, dangling spines that can grow several centimeters in length, giving them a shaggy or hair-like appearance. For example, *Hericium erinaceus* features cascading spines that resemble a lion's mane, while *Hericium americanum* has slightly shorter but equally dense spines. The arrangement of these spines is typically pendulous, hanging from the underside of the mushroom's fruiting body, which maximizes spore dispersal in the wind.

In contrast to the long spines of *Hericium*, some mushrooms have shorter, more stubby spines. The genus Sarcodon is a prime example, with species like *Sarcodon imbricatus* featuring thick, fleshy spines that are often forked or branched. These spines are usually tightly packed and can give the mushroom's underside a rough, bumpy texture. The shape and arrangement of these spines can vary depending on the species, but they generally provide a large surface area for spore production.

Finally, it's worth noting that some mushrooms have spines that are not uniform in size or shape. For instance, *Bankera fuligineoalba* has spines that vary in length and thickness, creating a textured appearance. Additionally, the arrangement of spines can differ, with some mushrooms having them evenly distributed, while others may have clusters or patches. These variations highlight the diversity of mushroom spine structures and their adaptations to different environments and spore dispersal strategies.

In summary, the spines of mushrooms exhibit remarkable diversity in shape, size, and arrangement, reflecting the unique evolutionary adaptations of each species. From the thick, rigid spines of *Hydnum* to the long, cascading spines of *Hericium*, and the stubby, branched spines of *Sarcodon*, each type serves a specific function in spore production and dispersal. Understanding these differences is not only crucial for mycologists but also for foragers and enthusiasts who seek to identify and appreciate the intricate beauty of mushrooms.

Salt's Effect: Can It Kill Mushrooms?

You may want to see also

Function of Spines: Spines aid in spore dispersal, protection, and environmental adaptation in mushroom species

The spines of mushrooms, often found in species like the hydnoid fungi (e.g., *Hydnum* and *Hericium*), serve multiple critical functions that enhance the organism's survival and reproductive success. One of the primary roles of these spines is spore dispersal. Unlike gilled mushrooms that release spores from the underside of their caps, spined mushrooms produce spores on the surface of their spines. This design increases the exposed surface area, allowing for more efficient spore release into the surrounding environment. When air currents or animals brush against the spines, spores are dislodged and carried away, facilitating colonization of new habitats. This mechanism ensures that the mushroom can propagate effectively even in still or low-wind conditions.

In addition to spore dispersal, mushroom spines play a significant role in protection. The spines act as a physical barrier against predators and pathogens. Their sharp or rigid structure can deter grazing animals, such as insects or slugs, which might otherwise consume the mushroom. Furthermore, the spines can trap moisture, creating a humid microenvironment around the spore-bearing surface. This moisture barrier not only protects the spores from desiccation but also inhibits the growth of competing microorganisms, reducing the risk of infection. In this way, spines contribute to the mushroom's overall resilience in its ecosystem.

Another important function of mushroom spines is their role in environmental adaptation. Spines are often highly specialized structures that allow mushrooms to thrive in specific ecological niches. For example, in humid environments, spines can help manage water retention, preventing excessive moisture from damaging the spore-bearing tissue. In drier conditions, the spines' surface area can maximize spore exposure to air, ensuring dispersal even with minimal wind. Additionally, the shape and density of spines can influence how the mushroom interacts with its surroundings, such as by providing anchor points in soil or on wood, enhancing stability in diverse substrates.

The spines also contribute to thermoregulation, a key aspect of environmental adaptation. By increasing the surface area exposed to the air, spines help dissipate heat, preventing the mushroom from overheating in direct sunlight or warm conditions. This is particularly important for species that grow in exposed areas, where temperature fluctuations can be extreme. Conversely, in cooler environments, the spines' structure can trap a layer of still air, providing insulation and protecting the mushroom's reproductive structures from frost or cold damage.

Lastly, the spines of mushrooms demonstrate evolutionary ingenuity in combining multiple functions into a single structure. Their design reflects a balance between the need for efficient spore dispersal, protection from threats, and adaptation to varying environmental conditions. This multifunctionality highlights the spines' significance in the life cycle of spined mushroom species, ensuring their continued survival and proliferation in diverse ecosystems. Understanding these functions not only sheds light on the biology of mushrooms but also underscores the intricate ways in which fungi interact with their environment.

Mushrooms: A Deadly Treat for Dogs' Livers

You may want to see also

Spine Formation Process: Spines develop from specialized cells called basidia during mushroom maturation

The spine formation process in mushrooms is a fascinating aspect of their development, rooted in the activity of specialized cells called basidia. Basidia are the primary spore-bearing cells found in the hymenium, the fertile, spore-producing layer of mushrooms. These cells play a pivotal role in the maturation of mushrooms, particularly in species where spines are a prominent feature. Spines, often referred to as "spine-like structures" or "teeth," are elongated, needle-like projections that replace the typical gills or pores in certain mushroom species. Their development is a highly coordinated process that begins with the differentiation of basidia.

During the early stages of mushroom maturation, basidia undergo a series of cellular changes that prepare them for spine formation. Each basidium typically produces four spores, but in spine-forming species, the basidia elongate and extend outward instead of releasing spores in the conventional manner. This elongation is driven by the rapid division and expansion of cells within the basidium, which eventually gives rise to the spine structure. The process is regulated by genetic and environmental factors, ensuring that spines develop in a manner that maximizes spore dispersal efficiency.

As the basidia continue to elongate, they form a slender, cylindrical structure that constitutes the spine. Unlike gills or pores, which are flat or rounded, spines provide a unique surface area for spore attachment and release. The surface of each spine is lined with basidiospores, which are produced at the tip or along the length of the basidium. This arrangement allows spores to be ejected more effectively into the surrounding environment, often aided by water droplets or air currents. The precise mechanism of spore release from spines varies among species but is generally optimized for the mushroom's ecological niche.

The maturation of spines is closely tied to the overall development of the mushroom fruiting body. As the mushroom grows, the hymenium thickens, and the basidia within it begin their transformation into spines. This process is synchronized with the expansion of the cap and the formation of other structures, such as the stipe (stem). Environmental conditions, such as humidity and temperature, play a critical role in ensuring that spine formation occurs at the appropriate stage of mushroom maturation. For example, adequate moisture is essential for the elongation of basidia and the subsequent development of spines.

In summary, the spine formation process in mushrooms is a specialized adaptation that relies on the activity of basidia during maturation. From the initial differentiation of these cells to their elongation into spines, the process is finely tuned to enhance spore dispersal. Understanding this mechanism not only sheds light on the biology of mushrooms but also highlights the diversity of reproductive strategies in the fungal kingdom. Spines, as a unique feature of certain mushroom species, exemplify the intricate relationship between cellular development and ecological function in fungi.

Slice Shiitake Like a Chef: Simple Cutting Techniques

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spines in Identification: Spines are key features for classifying and identifying mushroom species accurately

Spines in mushroom identification play a crucial role in accurately classifying and distinguishing between species. Unlike the gills or pores found in many mushrooms, spines are unique structures that hang vertically from the underside of the cap, resembling icicles or sharp projections. These spines are not merely decorative; they serve as a primary site for spore production and dispersal. When identifying mushrooms, mycologists and enthusiasts often focus on the characteristics of these spines, including their color, density, length, and shape. For instance, the Lion’s Mane mushroom (*Hericium erinaceus*) is easily recognizable by its long, cascading spines, which are a defining feature of the species. Understanding these traits is essential for precise identification, as similar-looking mushrooms can differ significantly in their spine morphology.

The density and arrangement of spines are particularly important in mushroom classification. Some species have closely packed spines, while others are more sparse, creating a distinct appearance. For example, the Hydnum genus, commonly known as hedgehog mushrooms, features spines that are evenly distributed and short, giving them a bristly texture. In contrast, species like *Hericium americanum* have longer, more pendulous spines that hang freely. Observing whether the spines are forked, branched, or simple can also narrow down the identification. These details are often documented in field guides and taxonomic keys, making them indispensable for accurate classification.

Color is another critical aspect of spines in mushroom identification. Spines can range from white and cream to yellow, brown, or even shades of purple, depending on the species. For instance, the spines of *Hydnellum peckii* are notable for their vivid red or pink color, earning it the common name "Bleeding Tooth Fungus." Changes in spine color with age or environmental conditions can also provide clues to a mushroom's identity. Mycologists often note whether the spines bruise or change color when handled, as this can be a diagnostic feature.

The texture and consistency of spines are additional features that aid in identification. Some spines are brittle and break easily, while others are flexible and resilient. For example, the spines of *Hericium* species are soft and almost spongy, contrasting with the firmer spines of *Hydnum* mushrooms. This tactile characteristic, combined with visual observations, helps differentiate between closely related species. Examining the base of the spines—whether they are attached directly to the cap or arise from a common tissue—further refines the identification process.

In practical terms, spines are often the first feature examined when identifying mushrooms in the field. By comparing observed spine characteristics to those described in reliable guides or databases, one can quickly narrow down the possibilities. For instance, if a mushroom has long, white, cascading spines, it is likely a *Hericium* species. Conversely, short, bristle-like spines suggest a *Hydnum* or similar genus. This systematic approach ensures accuracy and reduces the risk of misidentification, which is crucial for both scientific study and safe foraging.

In conclusion, spines are indispensable features for classifying and identifying mushroom species accurately. Their morphology, arrangement, color, texture, and other characteristics provide a wealth of information that distinguishes one species from another. By carefully observing and documenting these traits, mycologists and enthusiasts can confidently identify mushrooms and contribute to the broader understanding of fungal diversity. Mastery of spine identification is a fundamental skill in the study of mushrooms, bridging the gap between casual observation and precise taxonomy.

Maitake Mushrooms and Dogs: Safety, Benefits, and Risks Explained

You may want to see also

Ecological Role of Spines: Spines interact with insects and microorganisms, influencing mushroom ecology and survival

The spines of mushrooms, often found on species like the hedgehog mushroom (*Hydnum repandum*), serve critical ecological roles by interacting with insects and microorganisms. These structures are not merely decorative; they function as a defense mechanism against herbivores and pests. Insects, such as flies and beetles, are deterred by the physical barrier created by the spines, which makes it difficult for them to feed on the mushroom’s spore-bearing surface. This protective feature ensures the mushroom can mature and release its spores without significant damage, thereby enhancing its reproductive success. Additionally, the spines reduce the risk of fungal tissue being consumed before spore dispersal, which is vital for the mushroom’s survival and propagation in its habitat.

Beyond defense, mushroom spines also influence the behavior of microorganisms, particularly bacteria and fungi. The spines create a microhabitat that can trap moisture and organic debris, fostering conditions conducive to microbial growth. Certain microorganisms may colonize the spines, forming symbiotic relationships that benefit the mushroom. For example, some bacteria produce compounds that inhibit the growth of competing fungi or pathogens, indirectly protecting the mushroom. This microbial interaction highlights how spines contribute to the mushroom’s overall health and resilience in its environment.

Spines further play a role in regulating water retention and dispersal around the mushroom. Their structure can trap water droplets, which helps maintain hydration in drier conditions. This moisture retention is crucial for spore viability and dispersal, as hydrated spores are more likely to germinate successfully upon reaching a suitable substrate. Conversely, in humid environments, the spines can facilitate water runoff, preventing excessive moisture that might otherwise promote the growth of harmful molds or bacteria on the mushroom’s surface.

The ecological role of spines extends to their interaction with spore-dispersing insects. While some insects are deterred, others, such as certain flies and beetles, are attracted to the mushroom for spore dispersal. The spines do not impede these beneficial insects but instead guide their movement across the spore-bearing surface, ensuring efficient spore transfer. This dual function—deterring harmful insects while facilitating interactions with beneficial ones—demonstrates the spines’ adaptive significance in mushroom ecology.

Finally, the spines contribute to the mushroom’s integration into the broader ecosystem. By influencing insect and microbial interactions, they shape the local biodiversity and nutrient cycling processes. For instance, mushrooms with spines may support unique assemblages of decomposers and detritivores, which in turn affect soil health and nutrient availability. This ecological interplay underscores the importance of spines not only for individual mushroom survival but also for the functioning of forest and woodland ecosystems where these fungi thrive. Understanding these roles provides insights into the intricate relationships between fungi, their structures, and the organisms they interact with.

Enhancing Mushroom Potency: Simple Tricks for a Powerful Experience

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The spines of mushrooms, also known as "teeth," are the downward-pointing, needle-like structures found on the underside of certain mushroom caps, such as those in the Hydnum genus. They serve a similar function to gills, aiding in spore dispersal.

Mushroom spines differ from gills in their structure and appearance. While gills are thin, blade-like structures arranged radially, spines are individual, tooth-like projections. Spines are less common and are characteristic of specific mushroom families, like the hedgehog mushrooms.

The primary purpose of mushroom spines is to produce and release spores. As the mushroom matures, spores develop on the surface of the spines and are dispersed into the environment, allowing the fungus to reproduce and spread.