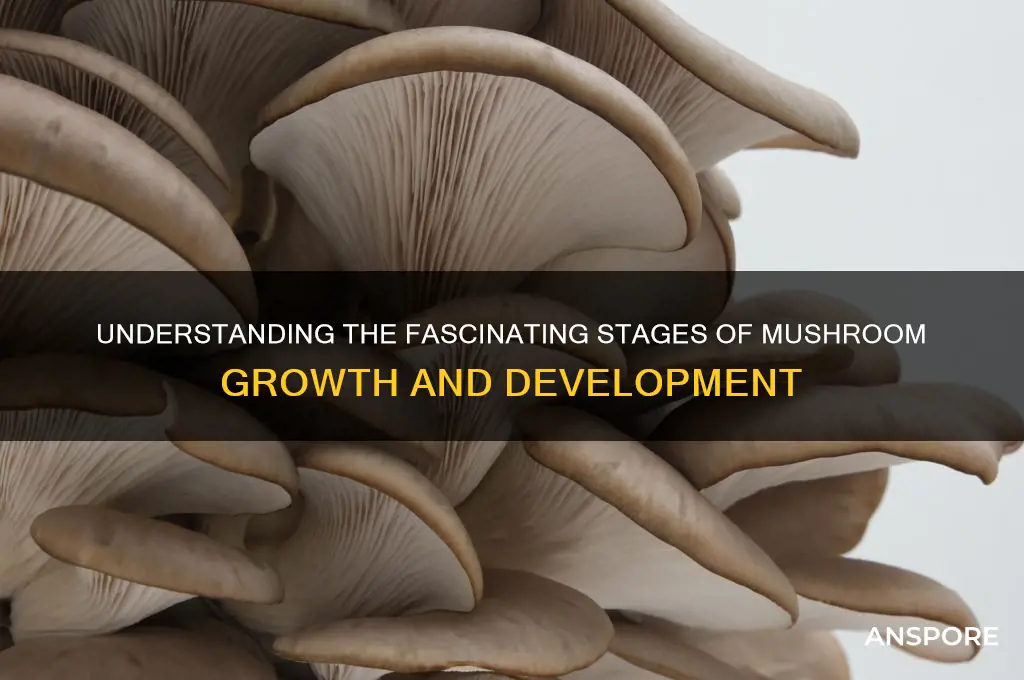

Mushroom growth is a fascinating process that occurs in distinct stages, each crucial for the development of these unique fungi. It begins with spore germination, where microscopic spores land on a suitable substrate and sprout, forming a network of thread-like structures called mycelium. As the mycelium expands and matures, it enters the vegetative growth stage, absorbing nutrients from its environment. Under the right conditions of moisture, temperature, and light, the mycelium initiates pinning, where small mushroom primordia emerge. These primordia then develop into mature mushrooms during the fruiting stage, characterized by the growth of the cap, stem, and gills. Finally, the mushroom releases spores through sporulation, completing the life cycle and ensuring the continuation of the species. Understanding these stages is essential for both cultivation and appreciating the intricate biology of mushrooms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Stage 1: Spore Germination | Spores land on a suitable substrate, absorb water, and germinate into hyphae. |

| Stage 2: Mycelium Growth | Hyphae grow and spread, forming a network called mycelium to absorb nutrients. |

| Stage 3: Primordia Formation | Mycelium aggregates into small, pinhead-like structures called primordia. |

| Stage 4: Fruiting Body Development | Primordia grow into mature mushrooms with a cap, gills, and stem. |

| Stage 5: Sporulation | Gills release spores, which are dispersed to start the cycle again. |

| Environmental Factors | Requires specific humidity, temperature, and substrate conditions for each stage. |

| Duration | Varies by species; typically 1-4 weeks from primordia to mature fruiting body. |

| Substrate | Organic matter like wood, soil, or compost, depending on the mushroom species. |

| Light Requirements | Indirect light is often needed for fruiting body development. |

| Common Species | Button mushrooms, shiitake, oyster mushrooms, and others follow similar stages. |

Explore related products

$14.99

What You'll Learn

- Spawn Run: Mycelium colonizes substrate, forming a dense network for nutrient absorption and growth

- Primordia Formation: Tiny pin-like structures emerge, signaling the start of mushroom development

- Fruiting Stage: Mushrooms grow rapidly, developing caps, gills, and stems for spore production

- Maturation Phase: Mushrooms reach full size, releasing spores to propagate the species

- Senescence: Mushrooms age, collapse, and decompose, returning nutrients to the substrate

Spawn Run: Mycelium colonizes substrate, forming a dense network for nutrient absorption and growth

The spawn run stage is a critical phase in the mushroom cultivation process, where the mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus, colonizes the substrate, establishing a robust foundation for future growth. This stage begins after the substrate, which can be a mixture of materials like straw, wood chips, or grain, has been pasteurized or sterilized to eliminate competing organisms. The mycelium, typically introduced in the form of spawn (grain colonized by mycelium), is mixed or layered into the substrate. Over time, the mycelium extends its hyphae—microscopic, thread-like structures—throughout the substrate, breaking down complex organic matter into simpler nutrients that it can absorb. This colonization process is essential for the mushroom’s lifecycle, as it ensures the mycelium has access to the necessary resources for energy and growth.

During the spawn run, the mycelium forms a dense, white, cobweb-like network that binds the substrate together. This network is highly efficient at absorbing water and nutrients, such as carbohydrates, proteins, and minerals, from the surrounding material. The mycelium’s ability to secrete enzymes plays a key role here, as these enzymes degrade the substrate’s components into forms the fungus can utilize. Temperature and humidity are critical factors during this stage; optimal conditions (typically 70–75°F or 21–24°C and high humidity) encourage rapid and uniform colonization. Proper aeration is also important to prevent the buildup of carbon dioxide, which can inhibit mycelial growth. Cultivators often monitor the substrate closely, ensuring it remains undisturbed to allow the mycelium to spread uninterrupted.

The duration of the spawn run varies depending on factors like the mushroom species, substrate type, and environmental conditions, but it generally takes 1 to 3 weeks. For example, oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) colonize substrates relatively quickly, while shiitake mushrooms (*Lentinula edodes*) may take longer. During this period, the substrate’s appearance changes significantly as the mycelium spreads, often turning completely white. This transformation indicates that the mycelium has successfully established itself and is ready to move into the next stage of growth. Patience is key during the spawn run, as rushing the process can lead to incomplete colonization and poor fruiting.

To support the spawn run, cultivators must maintain a clean and controlled environment to prevent contamination by molds, bacteria, or other fungi. Even a small amount of contamination can outcompete the mycelium for resources, derailing the entire cultivation process. Regular inspection of the substrate for signs of contamination, such as discoloration or unusual odors, is crucial. Additionally, maintaining proper moisture levels is vital, as overly dry conditions can slow colonization, while excessive moisture can lead to anaerobic conditions or mold growth. By carefully managing these factors, cultivators ensure the mycelium thrives and prepares for the next stage: primordia formation and fruiting.

In summary, the spawn run is a foundational stage where the mycelium colonizes the substrate, creating a dense network for nutrient absorption and growth. This phase requires precise control of environmental conditions, including temperature, humidity, and aeration, to support efficient colonization. By successfully completing the spawn run, cultivators set the stage for healthy mushroom development, ensuring a bountiful harvest in the subsequent stages of the cultivation process.

Mushroom Sales in Colorado: What's the Deal?

You may want to see also

Primordia Formation: Tiny pin-like structures emerge, signaling the start of mushroom development

Primordia formation is a critical and fascinating stage in the mushroom growth cycle, marking the transition from invisible mycelial activity to visible fruiting body development. During this phase, the mycelium, which has been silently spreading and colonizing its substrate, begins to aggregate and differentiate into tiny, pin-like structures known as primordia. These structures are the earliest recognizable signs of mushroom formation and typically appear as small, white or light-colored bumps on the substrate surface or within the growing medium. The emergence of primordia is a clear indication that environmental conditions—such as humidity, temperature, and light—have aligned to trigger fruiting.

The process of primordia formation is driven by complex cellular and biochemical changes within the mycelium. As the mycelium senses optimal conditions, it redirects its energy toward vertical growth, initiating the development of these pin-like structures. Each primordium consists of densely packed hyphae that begin to organize into the rudimentary forms of a mushroom’s cap, stem, and gills. This stage is highly sensitive to environmental fluctuations; factors like insufficient humidity or drastic temperature changes can halt or reverse primordia development, underscoring the need for stable growing conditions.

For cultivators, recognizing and nurturing primordia is essential for successful mushroom cultivation. At this stage, maintaining high humidity levels (around 90-95%) is crucial to prevent the primordia from drying out and aborting. Gentle airflow and indirect light can also support healthy development, as they mimic natural conditions that encourage fruiting. Observing primordia allows growers to anticipate the next stages of growth and prepare accordingly, such as adjusting ventilation or providing additional support for larger fruiting bodies.

Primordia formation is a testament to the mushroom’s adaptability and resilience. Despite their minuscule size, these structures represent a significant investment of energy by the mycelium, signaling its commitment to producing spores for reproduction. The successful progression from primordia to mature mushrooms depends on the continued availability of resources and favorable conditions. Thus, this stage serves as a critical checkpoint in the mushroom’s life cycle, bridging the gap between unseen mycelial networks and the visible, spore-producing organisms we recognize as mushrooms.

In summary, primordia formation is a pivotal moment in mushroom development, where tiny pin-like structures emerge as the first visible signs of fruiting. This stage requires precise environmental management and highlights the intricate processes underlying mushroom growth. By understanding and supporting primordia formation, cultivators can ensure the healthy progression of mushrooms through their life cycle, ultimately leading to a successful harvest.

Mushrooms Decriminalized in Oregon: What Does This Mean?

You may want to see also

Fruiting Stage: Mushrooms grow rapidly, developing caps, gills, and stems for spore production

The fruiting stage is a critical and visually striking phase in the mushroom growth cycle, marking the culmination of the fungus's development. During this stage, the mushroom rapidly transforms from a network of mycelium into the recognizable fruiting body we commonly associate with mushrooms. This process is triggered by environmental cues such as changes in temperature, humidity, and light, signaling to the mycelium that conditions are optimal for spore production. As the fruiting stage begins, the mushroom primordia, or "pins," emerge from the substrate, appearing as small, pinhead-like structures. These pins are the initial signs of the mushroom's reproductive effort, and they grow exponentially in size over a short period.

As the fruiting stage progresses, the mushroom develops its characteristic features: the cap, gills, and stem. The cap, or pileus, expands and takes shape, often starting as a rounded structure before flattening or taking on a more convex form depending on the species. Beneath the cap, the gills (or pores in some species) begin to form, serving as the primary site for spore production. These gills are tightly packed and delicate, providing a large surface area for the spores to develop and disperse. Simultaneously, the stem, or stipe, elongates to support the cap and elevate it above the substrate, ensuring that the spores can be effectively released into the surrounding environment.

The rapid growth during the fruiting stage is fueled by the mycelium's stored nutrients and the continued absorption of resources from the substrate. This phase is energetically demanding, as the mushroom invests heavily in developing its reproductive structures. The cap, gills, and stem are not just physical features but are finely tuned for spore dispersal. The gills, in particular, are designed to maximize spore production, with each gill edge lined with basidia—specialized cells that produce and release spores. This intricate development ensures that the mushroom can fulfill its primary goal: propagating the species through the widespread distribution of spores.

Environmental conditions play a pivotal role in the success of the fruiting stage. Optimal humidity is essential to prevent the mushroom from drying out, while adequate airflow ensures that spores can be efficiently released. Light exposure, though not always necessary, can influence the direction and rate of growth in some species. Growers cultivating mushrooms must carefully monitor these conditions to support healthy fruiting bodies. For example, maintaining a humid environment often involves misting or using humidifiers, while proper ventilation ensures that carbon dioxide levels remain low, promoting robust growth.

The fruiting stage is relatively short-lived compared to the earlier stages of mushroom growth, typically lasting from a few days to a couple of weeks. Once the mushroom has fully matured, it begins to release spores, often in vast quantities. This release can occur passively through air currents or actively through mechanisms like the forcible ejection of spores in certain species. After spore release, the mushroom's tissues may begin to degrade, signaling the end of its reproductive mission. However, the mycelium remains viable and can potentially initiate another fruiting cycle under favorable conditions, continuing the lifecycle of the fungus. Understanding and optimizing the fruiting stage is essential for both natural ecosystems and cultivated mushroom production, as it directly impacts the success of spore dispersal and the next generation of mushrooms.

Mushrooms: A Natural PCP Alternative?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Maturation Phase: Mushrooms reach full size, releasing spores to propagate the species

The maturation phase is a critical stage in the mushroom growth cycle, marking the culmination of the fungus's development. During this phase, mushrooms reach their full size and structural maturity, becoming visually prominent and distinct. The caps expand to their maximum diameter, and the gills or pores underneath develop fully, preparing for the next crucial step in the mushroom's life cycle. This stage is not just about physical growth but also about the mushroom's readiness to fulfill its reproductive role. As the mushroom matures, it transitions from a growing organism to a reproductive entity, setting the stage for spore release.

Once the mushroom has attained its full size, the primary focus shifts to spore production and release, a process essential for the propagation of the species. The gills or pores, which have been developing throughout the maturation phase, are now laden with spores. These spores are microscopic reproductive units that serve as the mushroom's seeds. The mushroom's structure is designed to facilitate spore dispersal, often relying on environmental factors like air currents, water, or even passing animals to carry the spores away. This dispersal mechanism ensures that the spores can reach new habitats, increasing the chances of successful colonization and growth.

The release of spores is a highly coordinated process, often triggered by environmental cues such as humidity, temperature, and light. As the mushroom matures, the cells in the gills or pores undergo changes that eventually lead to the discharge of spores. This release can occur in various ways, depending on the mushroom species. Some mushrooms actively eject spores using a forcible discharge mechanism, while others rely on passive methods, such as the spores simply falling off the gills due to gravity or air movement. Regardless of the method, the goal is the same: to disperse spores as widely as possible to ensure the survival and spread of the species.

During the maturation phase, the mushroom's appearance may also change to enhance spore dispersal. For instance, the cap may flatten or even curl upwards to expose the gills more effectively, increasing the surface area for spore release. Additionally, some mushrooms develop a delicate, powdery appearance on their gills as the spores mature, which can aid in their dispersal. These physical changes are adaptations that optimize the mushroom's reproductive success, ensuring that the spores are released efficiently and can travel to new locations.

The maturation phase is not only about the mushroom's individual growth but also about its contribution to the ecosystem. By releasing spores, mushrooms play a vital role in nutrient cycling and ecosystem dynamics. Spores that land in suitable environments will germinate and grow into new mycelium, continuing the life cycle. This phase highlights the mushroom's dual role as both a decomposer and a reproducer, breaking down organic matter while ensuring the continuation of its species. Understanding the maturation phase provides valuable insights into the intricate and fascinating world of mushroom biology and ecology.

Porcini Mushrooms: Secrets of Their Growth

You may want to see also

Senescence: Mushrooms age, collapse, and decompose, returning nutrients to the substrate

As mushrooms reach the final stage of their life cycle, they enter a phase known as senescence, where aging becomes apparent. This process is characterized by a gradual decline in the mushroom's structural integrity and overall vitality. The once firm and resilient fruiting body begins to weaken, marking the beginning of its inevitable collapse. During this stage, the mushroom's cells start to break down, and its tissues become more susceptible to external factors such as moisture loss and physical damage.

The collapse of the mushroom is a critical aspect of senescence, as it facilitates the subsequent decomposition process. As the mushroom's cap and stem lose their rigidity, they may droop, bend, or even disintegrate, exposing the delicate inner tissues to the surrounding environment. This exposure accelerates the breakdown of complex organic compounds, such as proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids, into simpler molecules. The mushroom's own enzymes, as well as microorganisms present in the substrate, play a significant role in this degradation process, effectively recycling the nutrients stored within the mushroom.

Decomposition is a vital part of the senescence stage, as it enables the return of essential nutrients to the substrate. As the mushroom breaks down, it releases a range of organic compounds, including nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, which are essential for the growth and development of future fungal generations. This nutrient recycling process is crucial for maintaining the health and fertility of the substrate, ensuring that the ecosystem can continue to support fungal growth. The decomposing mushroom also provides a food source for various microorganisms, further contributing to the overall nutrient cycling within the environment.

The rate of decomposition during senescence can vary depending on several factors, including the mushroom species, environmental conditions, and the presence of decomposers. In general, mushrooms with thinner, more delicate tissues tend to decompose more rapidly than those with thicker, tougher structures. Environmental factors such as temperature, humidity, and oxygen availability also play a significant role in determining the pace of decomposition. As the mushroom's tissues break down, they become increasingly susceptible to colonization by bacteria, fungi, and other decomposers, which further accelerate the nutrient release process.

As senescence progresses, the mushroom's remains eventually merge with the substrate, completing the nutrient cycle. The released nutrients become available for uptake by the mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus, which can then use these resources to support new growth and development. This closed-loop system ensures that the energy and materials invested in the mushroom's growth are not lost but rather reinvested in the ecosystem. By returning nutrients to the substrate, senescing mushrooms contribute to the overall sustainability and resilience of their environment, highlighting the importance of this often-overlooked stage in the mushroom growth cycle. Understanding the senescence process is crucial for appreciating the complex dynamics of fungal ecosystems and the vital role that mushrooms play in nutrient cycling and energy flow.

Mushrooms and Creatine: Are They Compatible?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The main stages of mushroom growth are mycelium colonization, pinning, fruiting, and maturation.

During mycelium colonization, the mushroom’s network of thread-like cells (mycelium) spreads through the substrate, absorbing nutrients and preparing for fruiting.

The pinning stage is when small, pin-like structures (primordia) begin to form on the substrate, marking the start of mushroom development.

The fruiting stage typically lasts several days, during which the mushroom grows rapidly in size, developing its cap, stem, and gills or pores.