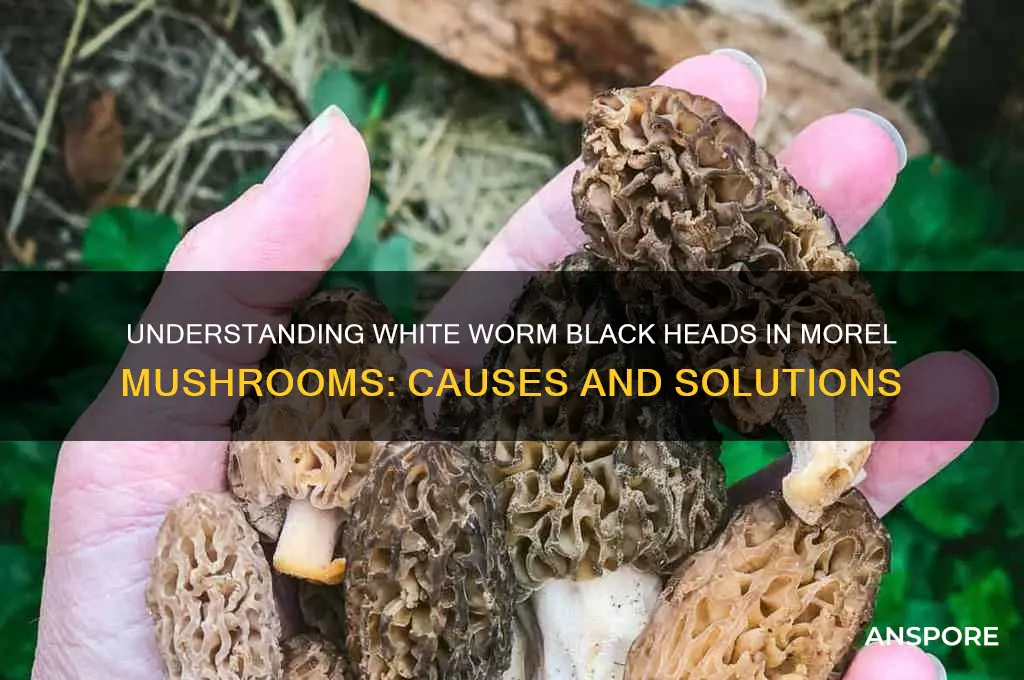

White worm black heads in morel mushrooms refer to a specific condition where the interior of the mushroom becomes infested with larvae, typically from insects like flies or beetles, which leave behind dark, visible spots or black heads as they feed. This issue often occurs when morels are not harvested promptly or are exposed to ideal conditions for insect activity. While the presence of these larvae does not necessarily render the mushroom toxic, it can significantly affect the texture, flavor, and overall quality of the morel, making it less desirable for culinary use. Identifying and avoiding infested mushrooms is crucial for foragers to ensure a safe and enjoyable harvest.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Common Name | White Worm Black Heads |

| Scientific Name | Not a specific species, but refers to a condition in morel mushrooms (Morchella spp.) |

| Cause | Infestation by larvae of insects, most commonly flies (e.g., Drosophila spp.) or beetles |

| Appearance | Small, white larvae visible inside the mushroom's hollow stem or cap; black heads of larvae may be seen protruding |

| Impact on Edibility | Generally considered unsafe to eat due to potential parasites or toxins introduced by the larvae |

| Prevention | Proper harvesting (inspect mushrooms carefully), refrigeration, and cooking thoroughly if consumed |

| Affected Morel Species | Various morel species, including yellow morels (Morchella esculenta) and black morels (Morchella elata) |

| Seasonal Occurrence | More common in warmer, humid conditions during the morel fruiting season |

| Geographic Distribution | Observed in morel-growing regions worldwide, particularly in North America and Europe |

| Identification Tip | Look for movement or small holes in the mushroom, indicating larval presence |

| Alternative Names | Wormy morels, infested morels |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- White Worm Identification: Tiny larvae often found inside morel mushrooms, visible as white worms

- Black Head Cause: Dark spores or decay create black spots, not always harmful to mushrooms

- Edibility Concerns: White worms and black heads may indicate spoilage; avoid if unsure

- Prevention Tips: Proper harvesting and storage reduce worm and black head occurrences in morels

- Impact on Flavor: Worms and black heads can affect texture and taste, altering morel quality

White Worm Identification: Tiny larvae often found inside morel mushrooms, visible as white worms

Morel mushrooms, prized by foragers for their unique flavor and texture, often harbor tiny, white larvae that can be a cause for concern. These larvae, commonly referred to as "white worms," are the immature stage of insects, typically flies or beetles, that lay their eggs within the mushroom’s spongy structure. While their presence may be off-putting, understanding their lifecycle and impact is key to handling them effectively. Most white worms are harmless to humans but indicate that the mushroom may be past its prime or has been compromised.

Identification is straightforward: these larvae are small, usually 1–5 mm in length, and appear as thin, translucent or creamy white worms wriggling within the mushroom’s ridges. They are most visible when the mushroom is cut open or soaked in water, a common practice to dislodge them. If you spot blackheads on these worms, it’s a sign they are mature larvae preparing to pupate, often visible as a darker, hardened segment near their anterior end. This stage is less common but confirms the infestation is advanced.

To remove white worms, start by gently brushing the mushroom’s exterior to dislodge surface debris. Next, soak the morels in salted water (1 tablespoon of salt per liter of water) for 15–20 minutes, agitating occasionally to encourage the larvae to exit. After soaking, rinse thoroughly under running water, ensuring all worms and residue are removed. For heavily infested mushrooms, consider blanching them in boiling water for 30 seconds before soaking, though this may alter their texture slightly. Always inspect cleaned mushrooms under bright light to ensure no larvae remain.

While white worms are not harmful if accidentally ingested, their presence can affect the mushroom’s taste and texture, making early detection crucial. Foragers should prioritize harvesting firm, unblemished morels and avoid those with visible holes or discoloration, as these are more likely to be infested. Storing morels in a breathable container (like a paper bag) in the refrigerator slows larval development but does not prevent it entirely. Consume or preserve (by drying or freezing) fresh morels within 2–3 days to minimize the risk of infestation.

In conclusion, white worms in morel mushrooms are a natural occurrence, but their management is essential for culinary enjoyment. By mastering identification, employing proper cleaning techniques, and practicing timely harvesting and storage, foragers can minimize their impact. While these larvae are not dangerous, their presence serves as a reminder of the delicate balance between nature and the kitchen, encouraging respect for the ingredients we gather.

Cross-Strain Mushroom Techniques: A Beginner's Guide

You may want to see also

Black Head Cause: Dark spores or decay create black spots, not always harmful to mushrooms

Morel mushrooms, prized by foragers for their unique flavor and texture, occasionally exhibit black spots on their caps, a phenomenon colloquially referred to as "black heads." Contrary to common concern, these spots are not always indicative of spoilage or toxicity. Instead, they often result from the presence of dark spores or natural decay processes. Dark spores, particularly from nearby fungi, can settle on morels, creating localized black patches. Similarly, as morels age, their cells may break down, leading to darkened areas that resemble decay but do not necessarily render the mushroom unsafe for consumption.

To distinguish between harmless black spots and problematic issues, examine the mushroom’s overall condition. If the blackened areas are dry, firm, and confined to the surface, they are likely caused by spores or natural aging. However, if the spots are accompanied by a slimy texture, foul odor, or widespread discoloration, the mushroom may be decaying and should be discarded. Foraging best practices dictate inspecting each morel individually, as even mushrooms growing in close proximity can vary in quality.

From a culinary perspective, morels with minor black spots can still be used safely. Simply trim the affected areas before cooking to ensure a visually appealing dish. For preservation, drying morels with surface spores can halt further discoloration and extend their shelf life. When rehydrating dried morels, discard any pieces that develop an off smell or texture, as these may indicate advanced decay. Proper storage in airtight containers in a cool, dry place can also minimize the risk of spoilage.

Understanding the cause of black heads empowers foragers to make informed decisions, reducing waste and maximizing yield. While dark spores and decay are natural occurrences, they serve as reminders of the delicate balance between harvesting and preservation. By focusing on the mushroom’s overall health rather than minor cosmetic imperfections, enthusiasts can confidently enjoy morels in their culinary creations. This nuanced approach not only enhances safety but also deepens appreciation for the complexities of foraging and fungi biology.

Mushrooms: More Animal or Vegetable?

You may want to see also

Edibility Concerns: White worms and black heads may indicate spoilage; avoid if unsure

White worms and black heads in morel mushrooms are often red flags for foragers. These abnormalities can signal spoilage, bacterial growth, or infestation, rendering the mushroom unsafe for consumption. While morels are prized for their earthy flavor and unique texture, their hollow structure makes them susceptible to pests and decay. White worms, typically the larvae of insects like flies, can burrow into the mushroom, compromising its integrity. Black heads, on the other hand, may indicate overmaturity or fungal degradation, which can produce toxins harmful to humans.

Foraging safely requires vigilance. If you encounter a morel with white worms or black heads, err on the side of caution and discard it. Even a single infested mushroom can spoil an entire batch if stored together. To minimize risk, inspect each mushroom carefully before harvesting. Look for signs of discoloration, unusual texture, or visible movement within the ridges. If the mushroom feels soft or emits a foul odor, it’s likely spoiled and should be avoided.

Cooking does not always eliminate the risks associated with spoiled morels. While heat can kill bacteria and larvae, toxins produced by decay or certain fungi may remain stable even after cooking. Consuming contaminated mushrooms can lead to symptoms like nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea. Foraging guides often emphasize the importance of freshness, but even seemingly fresh morels can harbor hidden issues. If you’re unsure about a mushroom’s condition, it’s better to leave it in the wild than risk illness.

Prevention is key when it comes to safe morel consumption. Store harvested mushrooms in breathable containers like paper bags, not plastic, to reduce moisture buildup. Refrigerate them promptly and use within 2–3 days for optimal freshness. If you’re new to foraging, consider going with an experienced guide who can help identify safe specimens. Remember, the thrill of finding morels should never outweigh the importance of safety. When in doubt, throw it out.

Do Portabella Mushrooms Contain Iron? Nutritional Facts Revealed

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Prevention Tips: Proper harvesting and storage reduce worm and black head occurrences in morels

Morel mushrooms, prized for their earthy flavor and unique texture, are often plagued by white worms and black heads, which can detract from their culinary appeal. These issues arise from improper harvesting and storage practices, allowing pests and decay to take hold. By adopting precise techniques, you can significantly reduce these occurrences and preserve the integrity of your morels.

Harvesting with Care: Timing and Technique

Harvest morels when they are mature but not overripe. Overripe morels are more susceptible to worm infestations and black head formation. Look for morels with caps that have just begun to open, avoiding those with fully exposed gills or signs of decay. Use a sharp knife or scissors to cut the stem at the base, leaving the mycelium undisturbed to encourage future growth. Avoid pulling or twisting the mushroom, as this can damage the soil ecosystem and increase vulnerability to pests.

Post-Harvest Handling: Cleaning and Preparation

After harvesting, gently clean morels by brushing off dirt and debris with a soft brush or cloth. Avoid washing them with water, as moisture can accelerate decay and black head formation. For morels with visible wormholes, slice them open to check for larvae. If infested, discard or use for cooking immediately, as freezing or drying can kill any remaining larvae but won’t improve appearance. Store cleaned morels in a breathable container, such as a paper bag or mesh basket, to maintain airflow and prevent moisture buildup.

Storage Strategies: Preserving Quality

Proper storage is critical to preventing worm and black head issues. For short-term storage (up to 3 days), keep morels in the refrigerator, loosely wrapped in a paper towel to absorb excess moisture. For long-term preservation, drying is the most effective method. Slice morels into ¼-inch thick pieces and dehydrate at 125°F (52°C) for 6–8 hours, or until completely dry and brittle. Store dried morels in an airtight container in a cool, dark place. Alternatively, freeze morels by blanching them in boiling water for 2 minutes, plunging into ice water, and then freezing in airtight bags. Properly dried or frozen morels can last up to a year without developing black heads or worm infestations.

Environmental Considerations: Reducing Risk

Harvest morels from clean, unpolluted areas to minimize the risk of contamination. Avoid over-harvesting in a single location, as this can disrupt the ecosystem and increase susceptibility to pests. Rotate harvesting sites annually to allow morel populations to recover. Additionally, monitor weather conditions, as prolonged wet periods can accelerate decay and worm activity. Harvesting after a dry spell can reduce the likelihood of encountering infested mushrooms.

By implementing these harvesting and storage practices, you can enjoy morels that are not only free from white worms and black heads but also retain their exceptional flavor and texture. Attention to detail at every stage—from the forest to the kitchen—ensures a superior mushroom experience.

The Quickest Way to Wash Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Impact on Flavor: Worms and black heads can affect texture and taste, altering morel quality

Morel mushrooms, prized for their earthy flavor and unique texture, can be compromised by the presence of white worms and black heads. These imperfections, often a result of fungal or insect activity, directly impact the mushroom’s culinary appeal. White worms, typically larvae of flies, burrow into the mushroom’s honeycomb-like structure, causing it to soften and lose its characteristic firmness. Black heads, a sign of overmaturity or decay, indicate that the mushroom’s cells are breaking down, releasing enzymes that alter its taste profile. Together, these issues can transform a prized morel into a mushy, off-flavored ingredient, detracting from its desirability in dishes like risottos or sautéed sides.

To mitigate these effects, chefs and foragers must inspect morels carefully before use. A simple yet effective method is to slice the mushroom lengthwise, revealing any hidden larvae or internal decay. If worms are present, submerging the morels in salted water for 15–20 minutes can coax the larvae out, though this may slightly dilute their flavor. For black heads, there’s no rescue—these mushrooms should be discarded, as their enzymatic changes are irreversible. Freezing morels immediately after harvest can also prevent worm infestations, preserving their texture and taste for future use.

The impact of worms and black heads extends beyond texture to flavor. Worms introduce a faint bitterness as they break down the mushroom’s tissues, while black heads contribute a sour or fermented note, overshadowing the morel’s natural nuttiness. This degradation is particularly noticeable in delicate preparations, such as cream-based sauces or raw applications, where the mushroom’s purity is paramount. Foraging best practices, like harvesting younger, firmer specimens and avoiding damp, overgrown areas, can reduce the risk of these issues, ensuring a superior sensory experience.

Comparatively, morels affected by worms or black heads pale in quality to their pristine counterparts. A healthy morel offers a satisfying snap when bitten, releasing a rich, forest-floor aroma. In contrast, compromised mushrooms feel spongy and emit a faintly acrid scent, signaling their decline. For culinary professionals, the difference is critical—a single tainted morel can taint an entire dish. Vigilance in selection and preparation is key, as even the most skilled chef cannot salvage a morel’s flavor once its integrity is lost.

Instructively, home cooks can adopt a few strategies to minimize the impact of these imperfections. First, always clean morels thoroughly, using a brush to remove surface debris before inspecting for internal issues. Second, cook affected mushrooms in heartier dishes, like stews or casseroles, where their altered texture and flavor are less noticeable. Finally, when in doubt, err on the side of caution—discard any morel that feels unusually soft or smells off. By prioritizing quality, even amateur foragers can ensure that their morel creations remain a culinary triumph.

Brown Mushrooms: Are They Safe to Eat?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

White worm black heads refer to morel mushrooms infested by larvae of insects like flies or beetles. The "black heads" are the larvae's posterior ends, visible through the mushroom's honeycomb caps.

While not toxic, morels with larvae are generally avoided due to their unappetizing appearance and potential for spoilage. Thoroughly cleaning and cooking can make them edible, but many foragers discard them.

Prevention is challenging, as larvae infest morels in the wild. Harvesting younger, firmer morels and storing them properly can reduce the risk, but infestation is a natural occurrence.

Larvae-infested morels may have a slightly off flavor or texture due to the presence of the worms. Proper cleaning and cooking can mitigate this, but uninfested morels are preferred for optimal taste.