Yellow mushrooms in plants, often striking in appearance, are a diverse group of fungi that can be found in various ecosystems, ranging from forests to gardens. These mushrooms, characterized by their vibrant yellow hues, belong to different species, some of which are edible and prized for their culinary uses, while others are toxic and can pose risks to humans and animals. Their presence in plant environments is typically associated with decomposing organic matter, as many yellow mushrooms play a crucial role in nutrient cycling by breaking down dead plant material. However, certain species can also form symbiotic relationships with plants, aiding in nutrient uptake, while others may act as pathogens, causing harm to their host plants. Understanding the specific type of yellow mushroom is essential, as it determines their ecological impact and potential uses or dangers.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Identification of Yellow Mushrooms

Yellow mushrooms can be a fascinating yet sometimes perplexing sight in gardens, forests, or other plant-rich areas. Identifying them accurately requires careful observation of their physical characteristics, habitat, and behavior. These mushrooms often belong to various species, each with unique traits that distinguish them from one another. When encountering a yellow mushroom, the first step is to examine its cap, which can vary in shade from pale lemon to vibrant gold. The cap’s shape, texture, and size are crucial identifiers. For instance, some yellow mushrooms, like the Sulphur Tuft (*Hypholoma fasciculare*), have a convex cap that becomes umbonate (with a central bump) as it matures, while others, such as the Golden Wax Cap (*Hygrocybe ceracea*), have a slimy or waxy texture.

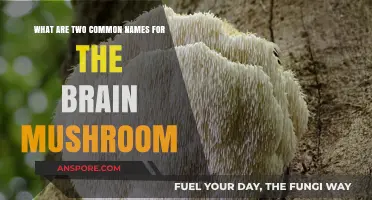

Next, observe the gills or pores underneath the cap, as these structures are vital for identification. Yellow mushrooms may have gills that are closely spaced or widely apart, and their color can range from pale yellow to deep orange. For example, the Witch’s Hat (*Hygrocybe conica*) has bright yellow gills that contrast with its conical cap. In contrast, some species, like the Lion’s Mane (*Hericium americanum*), have spines or teeth instead of gills, though they may not always be yellow, their presence is a distinguishing feature. The stem is another critical component. Note its color, length, thickness, and whether it has a ring or volva (a cup-like structure at the base). For instance, the Yellow Swamp Brittle Gilded (*Chanterelle*) has a smooth, yellow stem with a tapered base, while the Deadly Webcap (*Cortinarius rubellus*) may have a yellowish stem with a cortina (a cobweb-like partial veil).

The habitat of the yellow mushroom provides additional clues for identification. Some species, like the Golden Chanterelle (*Cantharellus cibarius*), thrive in woodland areas under coniferous or deciduous trees, forming symbiotic relationships with plant roots. Others, such as the Yellow Fieldcap (*Bolbitius titubans*), prefer grassy lawns or meadows. Observing whether the mushroom grows singly, in clusters, or in fairy rings can also narrow down its identity. For example, the Sulphur Tuft often grows in dense clusters on decaying wood, while the Witch’s Hat is commonly found in moist, nutrient-rich soil.

Finally, consider the spore print and odor of the mushroom, though these require more advanced techniques. A spore print is obtained by placing the cap gills-down on a piece of paper or glass overnight, revealing the color of the spores. Yellow mushrooms typically produce white, yellow, or cream-colored spores, which can help differentiate between species. Odor is another useful trait; for instance, the Golden Chanterelle has a fruity or apricot-like scent, while the Sulphur Tuft may smell pungent or greenish. Always exercise caution, as some yellow mushrooms, like the Deadly Webcap, are toxic and can be mistaken for edible varieties. Accurate identification is essential to avoid potential harm.

In summary, identifying yellow mushrooms involves a systematic approach: examine the cap, gills or pores, stem, and habitat, and consider additional factors like spore prints and odor. Each species has unique characteristics that, when observed carefully, can lead to a confident identification. Whether you’re a forager, gardener, or nature enthusiast, understanding these features will deepen your appreciation for the diverse world of yellow mushrooms in plants.

Mushroom Cut: A Trendy Haircut for All Ages

You may want to see also

Toxicity and Edibility Risks

Yellow mushrooms found in plants can vary widely in their characteristics, including their toxicity and edibility. While some yellow mushrooms are safe to eat and even prized in culinary traditions, others can be highly toxic, posing serious health risks. It is crucial to approach any yellow mushroom with caution, as misidentification can lead to severe consequences. Unlike cultivated mushrooms, wild yellow mushrooms often lack clear labels, making it essential to rely on accurate identification methods before consumption.

One of the most significant risks associated with yellow mushrooms is their potential toxicity. Certain species, such as the Amanita citrina (False Citron Amanita), contain toxins that can cause gastrointestinal distress, including vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. While this species is not typically fatal, its symptoms can be debilitating. More dangerous is the Amanita muscaria (Fly Agaric), which, although not always yellow, can present yellow or orange hues. This mushroom contains muscimol and ibotenic acid, causing hallucinations, confusion, and in severe cases, seizures or coma. Ingesting toxic yellow mushrooms can lead to long-term health issues or even death if not treated promptly.

Edibility risks are further compounded by the striking resemblance between toxic and edible yellow mushrooms. For example, the Cantharellus tubaeformis (Yellow Chanterelle) is a popular edible species known for its fruity aroma and forked gills. However, it can be confused with the Hygrocybe ceracea (Waxcap), which, while not fatally toxic, can cause mild gastrointestinal discomfort. Similarly, the Leucocoprinus birnbaumii (Yellow Houseplant Mushroom), commonly found in potted plants, is often mistaken for edible varieties but can cause digestive issues in sensitive individuals. These similarities highlight the importance of precise identification, ideally with the help of a mycologist or a reliable field guide.

Another critical aspect of toxicity and edibility risks is the preparation and consumption of yellow mushrooms. Even some edible species, when not properly cooked, can cause adverse reactions. For instance, raw Agaricus xanthodermus (Yellow-staining Mushroom) can lead to digestive problems, though it is generally considered edible when cooked. Additionally, individual sensitivities vary, and what is safe for one person may cause a reaction in another. Cross-contamination with toxic species during foraging or storage is also a risk, emphasizing the need for cleanliness and careful handling.

In conclusion, the toxicity and edibility risks of yellow mushrooms in plants cannot be overstated. While some species are safe and delicious, others are dangerous or even deadly. Proper identification, consultation with experts, and cautious preparation are essential steps to mitigate these risks. When in doubt, it is always safer to avoid consumption altogether, as the consequences of misidentification can be severe. Understanding these risks ensures a safer and more informed approach to interacting with yellow mushrooms in the wild or in cultivated environments.

Discover the Surprising Ingredients in Shirataki Mushroom Noodles

You may want to see also

Common Yellow Mushroom Species

Yellow mushrooms are a vibrant and diverse group of fungi that can be found in various ecosystems, often catching the eye of foragers, gardeners, and nature enthusiasts. While not all yellow mushrooms are safe to consume, understanding common species is essential for identification and safety. Below are some of the most common yellow mushroom species, their characteristics, and their roles in the environment.

One well-known yellow mushroom is the Golden Chanterelle (*Cantharellus cibarius*), a prized edible species found in forests across North America, Europe, and Asia. Its bright yellow to golden color, forked gills, and fruity aroma make it easily recognizable. Chanterelles grow in symbiotic relationships with trees, particularly oak and beech, and are highly sought after for their delicate flavor in culinary dishes. However, caution is advised, as they can be mistaken for the toxic "False Chanterelle" (*Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca*), which has true gills instead of forks.

Another common yellow mushroom is the Sulphur Tuft (*Hypholoma fasciculare*), often found in clusters on decaying wood. Its bright yellow cap and gills contrast with a greenish-yellow stem. While it is not fatally toxic, consuming Sulphur Tuft can cause gastrointestinal distress. This species is widespread in temperate regions and serves as a decomposer, breaking down wood and recycling nutrients in the ecosystem. Its presence often indicates decaying wood in the area.

The Waxcap (*Hygrocybe ceracea*) is a small, bright yellow mushroom commonly found in grasslands and lawns. Its waxy texture and vivid color make it stand out, though it is not typically consumed due to its insubstantial size and mild toxicity. Waxcaps are important indicators of healthy, undisturbed soil and are often associated with biodiverse ecosystems. Their presence is a sign of good soil quality and minimal chemical use.

Lastly, the Lemon Drop Fungus (*Bisporella citrina*) is a unique yellow mushroom that grows on decaying wood, often in a bright, almost fluorescent yellow color. Unlike the others, it is not a typical mushroom but a cup fungus, forming small, cup-like structures. While not edible, it plays a crucial role in wood decomposition and nutrient cycling. Its striking appearance makes it a favorite among mushroom photographers and enthusiasts.

In summary, common yellow mushroom species like the Golden Chanterelle, Sulphur Tuft, Waxcap, and Lemon Drop Fungus each have distinct characteristics and ecological roles. Proper identification is crucial, as some are edible and valuable, while others are toxic or inedible. Observing these mushrooms in their natural habitats provides insights into forest health, soil quality, and the intricate relationships between fungi and their environments. Always consult a field guide or expert before consuming any wild mushrooms.

Mushrooms: Nature's Opiates?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Habitat and Growth Conditions

Yellow mushrooms, often associated with plants, are typically fungi that form symbiotic or parasitic relationships with their host plants. These mushrooms thrive in specific habitats and require particular growth conditions to flourish. Understanding their habitat and growth requirements is essential for both enthusiasts and gardeners who wish to cultivate or manage them effectively.

Forest Environments and Decaying Matter

Yellow mushrooms are commonly found in forested areas, particularly in temperate and tropical regions. They favor environments rich in organic matter, such as decaying wood, leaf litter, and soil humus. Species like the *Laetiporus sulphureus*, also known as the "chicken of the woods," often grow on dead or dying hardwood trees. These mushrooms are saprotrophic, meaning they decompose dead plant material, recycling nutrients back into the ecosystem. Moist, shaded areas with ample fallen logs or stumps provide ideal conditions for their growth.

Soil and Moisture Requirements

The growth of yellow mushrooms is heavily dependent on soil moisture and composition. They thrive in well-drained, nutrient-rich soils with a slightly acidic to neutral pH. Consistent moisture is crucial, as fungi lack the ability to transport water over long distances. Mulch or compost-rich areas around plants can create a microhabitat conducive to mushroom growth. Overwatering or waterlogging, however, can hinder their development, as it may lead to root rot in host plants or suffocate the fungal mycelium.

Symbiotic Relationships with Plants

Some yellow mushrooms form mycorrhizal associations with plants, where the fungus and plant roots exchange nutrients. For example, certain species of *Amanita* mushrooms have symbiotic relationships with trees like oaks and pines. In such cases, the mushrooms grow near the base of the host plant, benefiting from the plant’s carbohydrates while providing essential minerals and water in return. Gardeners can encourage these relationships by planting compatible species together and avoiding excessive use of fungicides.

Temperature and Light Conditions

Yellow mushrooms typically prefer mild to cool temperatures, with optimal growth occurring between 50°F and 70°F (10°C and 21°C). Extreme heat or cold can inhibit their development. While they do not require direct sunlight, indirect or filtered light is beneficial for the host plants, which indirectly supports mushroom growth. Shaded areas, such as under canopies or near shrubs, provide the ideal balance of light and temperature for these fungi.

Seasonal Growth Patterns

The appearance of yellow mushrooms is often seasonal, with peak growth occurring in late summer to early autumn. This timing coincides with increased moisture from rainfall and cooler temperatures, which stimulate fungal activity. In regions with mild winters, some species may also emerge during spring. Monitoring seasonal changes and maintaining consistent environmental conditions can help predict and manage their growth in garden or natural settings.

By understanding and replicating these habitat and growth conditions, individuals can either foster the presence of yellow mushrooms or mitigate their growth if they are unwanted. Whether in a forest or a garden, these fungi play a vital role in ecosystems, making their study both fascinating and practical.

Exploring Mushroom Macros: Unique Nutritional Profiles in Fungi

You may want to see also

Ecological Role in Plant Systems

Yellow mushrooms in plant systems, often associated with mycorrhizal fungi or saprophytic species, play a crucial ecological role in maintaining soil health, nutrient cycling, and plant growth. These fungi form symbiotic relationships with plant roots, particularly through mycorrhizal associations, which enhance the plant’s ability to absorb water and nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen. In this mutualistic relationship, the fungus receives carbohydrates produced by the plant through photosynthesis, while the plant benefits from the fungus’s extensive hyphal network, which increases its access to soil resources. This partnership is especially vital in nutrient-poor soils, where yellow mushrooms, such as species from the *Amanita* or *Cantharellus* genera, contribute significantly to plant survival and productivity.

Beyond mycorrhizal interactions, yellow mushrooms also function as decomposers in plant ecosystems. Saprophytic yellow mushrooms, such as those from the *Hypholoma* genus, break down organic matter like dead plant material, wood, and leaf litter. This decomposition process recycles essential nutrients back into the soil, making them available for uptake by living plants. By accelerating the breakdown of complex organic compounds, these fungi play a key role in nutrient cycling, ensuring the continuous availability of elements like carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus, which are critical for plant growth and ecosystem functioning.

Yellow mushrooms further contribute to soil structure and stability. As their mycelial networks grow, they bind soil particles together, improving soil aggregation and reducing erosion. This enhanced soil structure promotes water retention and infiltration, benefiting plant roots by ensuring a consistent supply of moisture. Additionally, the presence of these fungi can influence soil microbial communities, fostering a diverse and balanced ecosystem that supports overall plant health and resilience against pathogens and environmental stressors.

In forest ecosystems, yellow mushrooms often act as indicators of ecological health. Their presence typically signifies well-established fungal networks and healthy soil conditions, which are essential for the growth of trees and understory plants. For example, yellow chanterelles (*Cantharellus cibarius*) are commonly found in coniferous and deciduous forests, where they contribute to the nutrient dynamics and overall biodiversity of the ecosystem. Their ecological role extends to supporting food webs, as they serve as a food source for various organisms, including insects, small mammals, and microorganisms, thereby linking fungal communities to broader ecosystem processes.

Lastly, yellow mushrooms participate in allelopathic interactions within plant systems, influencing plant community composition and competition. Some species produce secondary metabolites that can inhibit the growth of certain plants or pathogens, indirectly benefiting their host plants. This chemical mediation can shape plant diversity and distribution, ensuring that resources are allocated efficiently within the ecosystem. By fulfilling these diverse ecological roles, yellow mushrooms are integral to the functioning and sustainability of plant systems, highlighting their importance in both natural and managed environments.

The Magic of Reconstituting Dried Mushrooms: A Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yellow mushrooms in plants are fungi that grow in or around plant environments, characterized by their yellow coloration. They are not part of the plant itself but are separate organisms that thrive in moist, organic-rich soil or decaying plant matter.

Not necessarily. Most yellow mushrooms are saprotrophic, meaning they decompose organic material and do not harm living plants. However, some species can indicate poor soil health or excessive moisture. Rarely, certain yellow mushrooms may be toxic if ingested, so avoid handling or consuming them without proper identification.

To reduce yellow mushroom growth, improve soil drainage, reduce overwatering, and remove decaying plant debris. Ensuring proper airflow and sunlight in the area can also discourage fungal growth. If mushrooms persist, it may indicate a need to amend the soil or address underlying moisture issues.