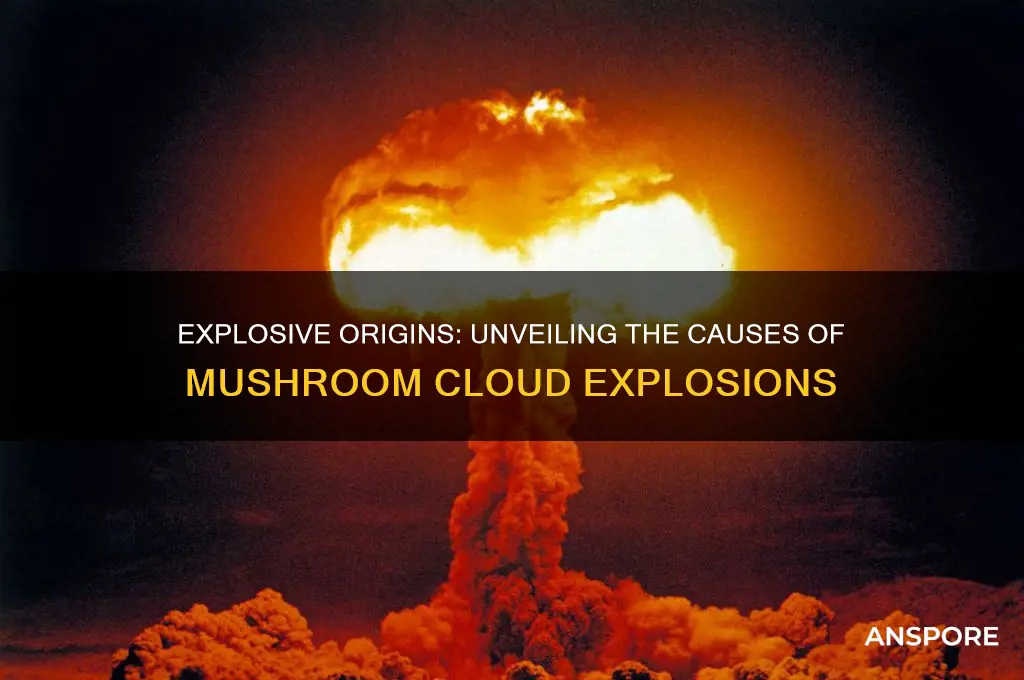

A mushroom cloud explosion, often associated with nuclear detonations, can also result from other high-energy events such as large-scale chemical explosions, volcanic eruptions, or even meteor impacts. In the case of nuclear explosions, the cloud forms due to the rapid heating of air and the subsequent rise of a massive fireball, which cools and flattens at the top while drawing in surrounding air and debris, creating the distinctive mushroom shape. Chemical explosions, like those involving fuel or industrial materials, can produce similar effects if they release enough energy rapidly. Natural phenomena, such as volcanic eruptions, generate mushroom clouds through the forceful expulsion of ash, gas, and rock into the atmosphere. Understanding the causes of these explosions is crucial for assessing risks, mitigating disasters, and comprehending the physics behind such powerful events.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Nuclear Explosions | The most common cause; results from fission or fusion reactions. |

| Explosive Yield | Typically requires yields above 1 kiloton (1,000 tons of TNT equivalent). |

| Fireball Formation | Initial blast creates a fireball with temperatures exceeding 1,000,000°C. |

| Stem Formation | Rising hot gases and debris create a vertical column (stem). |

| Cap Formation | Horizontal spread of debris and condensation forms the cap. |

| Thermodynamic Effects | Rapid expansion and cooling of gases drive the cloud's shape. |

| Volcanic Eruptions | Rare but possible; requires massive explosive eruptions (e.g., Plinian). |

| Meteor Impacts | High-energy impacts can create mushroom clouds due to explosive force. |

| Industrial Explosions | Extremely rare; would require unprecedented scale (e.g., massive fuel detonation). |

| Chemical Explosions | Insufficient energy to produce a mushroom cloud; limited to fireballs. |

| Environmental Factors | Atmospheric conditions (humidity, wind) influence cloud formation. |

| Historical Examples | Atomic bombings (Hiroshima, Nagasaki), nuclear tests (e.g., Trinity). |

Explore related products

$15.49 $19.99

What You'll Learn

- Nuclear Detonations: Atomic bombs create massive energy release, forming iconic mushroom clouds

- Volcanic Eruptions: Explosive eruptions eject ash and gas, mimicking mushroom cloud formations

- Thermobaric Weapons: Fuel-air explosives generate powerful blasts with cloud-like shockwaves

- Meteor Impacts: High-velocity collisions release energy, producing mushroom-shaped debris plumes

- Industrial Explosions: Large-scale chemical or fuel blasts can create similar cloud patterns

Nuclear Detonations: Atomic bombs create massive energy release, forming iconic mushroom clouds

The mushroom cloud, a symbol of immense destructive power, is most famously associated with nuclear detonations. When an atomic bomb explodes, it unleashes a staggering amount of energy in a fraction of a second. This energy is released through nuclear fission, where the nuclei of heavy elements like uranium or plutonium split, triggering a chain reaction. The process generates temperatures exceeding millions of degrees Celsius, creating a fireball that rapidly expands and rises, drawing in surrounding air and debris. As the hot gases cool, they condense, forming the distinctive cap of the mushroom cloud, while the stem consists of dust, smoke, and vaporized materials sucked upward by the rising convection currents.

To understand the scale of this phenomenon, consider the energy released by the first atomic bomb detonated in 1945, codenamed "Little Boy." It yielded approximately 15 kilotons of TNT equivalent, instantly vaporizing everything within a radius of several hundred meters. Modern nuclear weapons can be far more powerful, with yields reaching into the megaton range. For instance, the Tsar Bomba, tested by the Soviet Union in 1961, had a yield of 50 megatons, creating a mushroom cloud visible from hundreds of kilometers away. The height of such clouds can reach tens of kilometers, depending on the bomb's yield and the altitude of the detonation.

While the mushroom cloud is a hallmark of nuclear explosions, its formation is not unique to atomic bombs. Volcanic eruptions, large-scale chemical explosions, and even meteor impacts can produce similar cloud structures under the right conditions. However, nuclear detonations stand out due to their unparalleled energy density and the rapidity of the explosion. The key difference lies in the source of energy: nuclear reactions release millions of times more energy per unit mass than chemical reactions, ensuring that the resulting cloud is both larger and more enduring.

From a practical standpoint, the mushroom cloud serves as a stark visual reminder of the catastrophic consequences of nuclear warfare. Its formation is a complex interplay of physics, chemistry, and meteorology, but its message is simple: the power to destroy on such a scale demands caution and responsibility. Understanding the science behind these clouds can help policymakers, scientists, and the public appreciate the urgency of nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation efforts. As we reflect on the history and potential future of nuclear weapons, the mushroom cloud remains a powerful symbol of both human ingenuity and the fragility of our existence.

Can You Eat Turkey Tail Mushroom? Benefits, Risks, and Preparation Tips

You may want to see also

Volcanic Eruptions: Explosive eruptions eject ash and gas, mimicking mushroom cloud formations

Nature’s most dramatic displays of power often rival human-made catastrophes, and volcanic eruptions stand as a prime example. When a volcano erupts explosively, it unleashes a column of ash, gas, and rock fragments that can rise miles into the atmosphere, forming a structure eerily reminiscent of a mushroom cloud. This phenomenon occurs due to the rapid expansion of volcanic gases, such as water vapor, carbon dioxide, and sulfur dioxide, which are trapped under immense pressure within the magma. When the pressure is released, these gases escape violently, propelling ash and debris skyward in a towering plume. The resulting cloud spreads laterally at high altitudes, creating the distinctive cap-like shape that mirrors nuclear explosions.

To understand the mechanics, consider the role of magma viscosity and gas content. Highly viscous magma, like that found in stratovolcanoes, traps gases more effectively, leading to greater pressure buildup. When this magma nears the surface, the sudden drop in pressure causes it to fragment explosively, ejecting material with tremendous force. For instance, the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens in Washington State produced a mushroom cloud that reached 80,000 feet in less than 15 minutes. Such eruptions are not merely geological events; they are atmospheric disruptors, injecting millions of tons of ash and aerosols into the stratosphere, where they can influence climate patterns for years.

Practical observation of these events requires both caution and preparation. If you live near an active volcano, familiarize yourself with local warning systems and evacuation routes. During an eruption, ashfall can pose respiratory hazards, so keep N95 masks on hand for all household members. Vehicles should be parked indoors to protect engines from abrasive ash, and water sources should be covered to prevent contamination. For scientists and enthusiasts, monitoring tools like seismometers and gas sensors provide critical data on volcanic activity, helping predict eruptions and their potential scale.

Comparatively, while nuclear mushroom clouds result from rapid energy release through fission or fusion, volcanic clouds stem from the release of mechanical and thermal energy stored in magma and gases. Both phenomena highlight the immense power stored beneath the Earth’s surface, whether in the form of radioactive isotopes or molten rock. However, volcanic eruptions offer a unique opportunity for study, as they are natural, recurring events that allow researchers to refine models of explosive processes. By analyzing ash composition and eruption dynamics, scientists can better understand not only volcanic hazards but also analogous processes, such as asteroid impacts or industrial explosions.

In conclusion, volcanic eruptions serve as a vivid reminder of the Earth’s dynamic nature, producing mushroom clouds that rival human-made disasters in scale and impact. From the physics of gas expansion to the practical steps for safety, these events offer both scientific insight and actionable guidance. Whether you’re a researcher, a resident of a volcanic region, or simply an observer of nature’s wonders, understanding these eruptions deepens our appreciation for the forces that shape our planet.

Are Pasture-Grown Mushrooms Safe to Eat? A Foraging Guide

You may want to see also

Thermobaric Weapons: Fuel-air explosives generate powerful blasts with cloud-like shockwaves

Thermobaric weapons, often referred to as fuel-air explosives (FAEs), are a class of devastating munitions designed to maximize blast effects. Unlike conventional explosives that rely on a single detonation, thermobaric weapons employ a two-stage process. First, a dispersing charge spreads a fine cloud of combustible fuel particles into the air. This cloud, often invisible and highly volatile, is then ignited by a second charge, creating a massive fireball and a powerful shockwave. The result is a blast wave that mimics the characteristic mushroom cloud shape, albeit on a smaller scale compared to nuclear explosions.

The destructive power of thermobaric weapons lies in their ability to consume oxygen rapidly, creating a vacuum that enhances the blast's force. This oxygen deprivation, combined with the intense heat and pressure, makes them particularly effective against fortified structures, bunkers, and even personnel in open areas. For instance, a single thermobaric warhead can generate a blast wave capable of leveling buildings and causing severe damage over a wide radius. The Russian military's use of thermobaric weapons in various conflicts has demonstrated their effectiveness in urban warfare, where traditional explosives might be less efficient due to the need for direct impact.

From a tactical perspective, thermobaric weapons offer a unique advantage in modern warfare. Their ability to generate a cloud-like shockwave allows them to penetrate and devastate enclosed spaces, making them ideal for neutralizing enemy positions in complex terrains. However, their use raises significant ethical and humanitarian concerns. The indiscriminate nature of the blast and the potential for widespread collateral damage have led to international scrutiny and calls for regulation. Despite this, thermobaric weapons continue to be developed and deployed by several nations, highlighting the ongoing debate between military utility and ethical responsibility.

For those interested in understanding the technical aspects, the design of thermobaric weapons involves precise engineering. The fuel used is typically a volatile substance like ethylene oxide or propylene oxide, which is aerosolized to create a fine mist. The dispersion mechanism must ensure an optimal cloud density for maximum combustion efficiency. The ignition system, often a high-explosive charge, must be timed perfectly to ignite the cloud at its peak dispersion. This intricate process requires advanced materials and expertise, making thermobaric weapons a sophisticated yet controversial tool in modern arsenals.

In conclusion, thermobaric weapons represent a specialized category of explosives that harness the power of fuel-air mixtures to create devastating mushroom cloud-like explosions. Their unique mechanism of action, combining fuel dispersion and ignition, results in blasts that are both visually striking and highly destructive. While their military applications are undeniable, the ethical implications of their use cannot be ignored. As technology advances, the international community must grapple with the balance between leveraging such powerful tools and ensuring they are used responsibly to minimize harm to civilians and infrastructure.

Mushroom Soy Sauce Magic: Versatile Recipe Ideas to Elevate Your Dishes

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Meteor Impacts: High-velocity collisions release energy, producing mushroom-shaped debris plumes

High-velocity collisions between meteors and Earth’s surface release energy on a scale that defies human imagination. When a meteor strikes, its kinetic energy transforms into thermal and mechanical forces, vaporizing rock and ejecting debris at speeds exceeding 10 kilometers per second. This explosive release creates a characteristic mushroom-shaped plume, similar to those observed in nuclear detonations. The plume’s stem forms as molten material and vaporized rock surge upward, while the cap expands as debris cools and spreads laterally, driven by atmospheric interaction. This phenomenon is not merely theoretical; it’s documented in events like the 1908 Tunguska impact, where an airburst flattened 2,000 square kilometers of forest, leaving a debris cloud visible for days.

To understand the mechanics, consider the energy involved. A meteor just 30 meters in diameter, traveling at 20 kilometers per second, can release energy equivalent to 10 megatons of TNT—over 500 times the yield of the Hiroshima bomb. This energy doesn’t just create a crater; it generates a shockwave that propels debris skyward, forming the plume’s initial column. As this column rises, it cools and interacts with the atmosphere, creating the distinctive cap. The process is akin to a volcanic eruption but far more rapid and violent, with debris reaching altitudes of 50 kilometers or more. For comparison, Mount St. Helens’ 1980 eruption produced a plume that peaked at 24 kilometers, highlighting the sheer scale of meteor impacts.

Practical observation of such events is rare but not impossible. Amateur astronomers and citizen scientists can contribute by monitoring fireball networks, which track meteor trajectories and estimate impact energy. If you witness a fireball, note its duration, brightness, and direction—data that can help scientists model potential debris plumes. For those near impact sites, safety is paramount: stay at least 10 kilometers away from fresh craters, as residual heat and unstable terrain pose risks. Historical impact sites, like Arizona’s Barringer Crater, offer safer opportunities to study plume remnants, such as shocked quartz and melt glass, which provide clues about the explosion’s intensity.

Comparing meteor impacts to other mushroom cloud causes reveals unique distinctions. Nuclear explosions rely on rapid energy release from fission or fusion, creating a plume through heated gases and vaporized ground material. Volcanic eruptions, on the other hand, produce plumes through sustained gas and ash ejection. Meteor impacts combine elements of both: an instantaneous energy release like a nuclear blast, coupled with the debris ejection of a volcanic event. This hybrid mechanism explains why meteor plumes often exhibit thicker stems and more expansive caps than their counterparts, as seen in satellite imagery of the 2013 Chelyabinsk meteor, whose plume persisted for hours.

In conclusion, meteor impacts offer a natural, if infrequent, example of mushroom cloud formation driven by high-velocity collisions. Their plumes are not just visually striking but scientifically valuable, providing insights into Earth’s history and the physics of extreme energy release. By studying these events, we gain a deeper understanding of our planet’s vulnerability to extraterrestrial forces and the processes that shape its surface. Whether through historical analysis, citizen science, or direct observation, the study of meteor-induced plumes remains a critical—and awe-inspiring—field of inquiry.

Mushroom Consumption and Candida: Can Overindulgence Lead to Overgrowth?

You may want to see also

Industrial Explosions: Large-scale chemical or fuel blasts can create similar cloud patterns

Industrial explosions, particularly those involving large-scale chemical or fuel blasts, can produce mushroom cloud patterns strikingly similar to those seen in nuclear detonations. These events occur when a massive amount of energy is released in a confined or semi-confined space, causing a rapid expansion of hot gases and debris. For instance, the 2015 Tianjin port explosion in China, which involved the detonation of hundreds of tons of hazardous chemicals, generated a mushroom cloud visible for miles. The key factor here is the sudden release of energy, often measured in tons of TNT equivalent, which creates a shockwave and lifts particulate matter high into the atmosphere, forming the distinctive cap and stem structure.

Understanding the mechanics of such explosions requires a focus on the materials involved. Chemical plants often store volatile substances like ammonium nitrate, which, when ignited, can release energy at rates comparable to small nuclear blasts. For example, the 1947 Texas City disaster involved the detonation of approximately 2,300 tons of ammonium nitrate, resulting in a mushroom cloud and widespread destruction. To mitigate risks, industrial facilities must adhere to strict safety protocols, including proper storage, ventilation, and emergency response plans. Regular inspections and employee training are critical, as even minor lapses can lead to catastrophic outcomes.

A comparative analysis reveals that while nuclear explosions rely on fission or fusion reactions, industrial blasts derive their energy from rapid chemical reactions. However, the visual and destructive similarities are undeniable. Both phenomena create a rising column of hot gases, which cools and spreads at high altitudes, forming the "cap" of the mushroom cloud. The primary difference lies in the composition of the debris: nuclear explosions release radioactive particles, whereas industrial blasts disperse chemical residues and combustion byproducts. This distinction is crucial for emergency responders, as it dictates the type of protective gear and decontamination procedures required.

From a practical standpoint, preventing industrial mushroom cloud explosions hinges on proactive measures. Facilities handling flammable or reactive materials should implement explosion-proof equipment, such as sealed electrical systems and inert gas blanketing. Additionally, real-time monitoring of temperature, pressure, and chemical concentrations can provide early warnings of potential hazards. In the event of an explosion, evacuation protocols must prioritize downwind areas, as the cloud’s trajectory depends on wind patterns and atmospheric conditions. Post-incident analysis should focus on identifying root causes, whether human error, equipment failure, or regulatory gaps, to prevent recurrence.

Finally, the environmental and health impacts of industrial mushroom clouds cannot be overstated. Chemical plumes can contaminate air, water, and soil, posing long-term risks to ecosystems and human populations. For example, the release of toxic gases like nitrogen oxides or sulfur dioxide can exacerbate respiratory conditions and contribute to acid rain. Communities near industrial sites must be equipped with air quality sensors and emergency shelters. Governments and industries alike must invest in research and technology to minimize the likelihood of such events, ensuring that the lessons of past disasters inform future safety standards.

Can Dogs Safely Eat Shiitake Mushrooms? A Pet Owner's Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A mushroom cloud explosion is a distinctive pyrocumulus cloud formed by the rapid expansion of hot gases and debris following a large explosion, typically associated with nuclear detonations, but also occurring in some large conventional explosions.

In a nuclear blast, the mushroom cloud is caused by the intense heat and energy released by the detonation, which creates a massive fireball. As the hot gases rise, they cool and form a mushroom-shaped cloud composed of water vapor, debris, and radioactive particles.

Yes, extremely large conventional explosions, such as those from massive fuel-air explosives or the destruction of large structures, can produce mushroom clouds. However, these are typically smaller and less defined than those from nuclear explosions.

The environment, particularly atmospheric conditions like humidity, temperature, and wind, influences the shape and size of a mushroom cloud. For example, high humidity can enhance condensation, making the cloud more visible, while wind can distort its shape.

Yes, mushroom cloud explosions are always the result of extremely powerful and destructive events, whether nuclear or large-scale conventional explosions. They are not formed by smaller or less intense blasts.