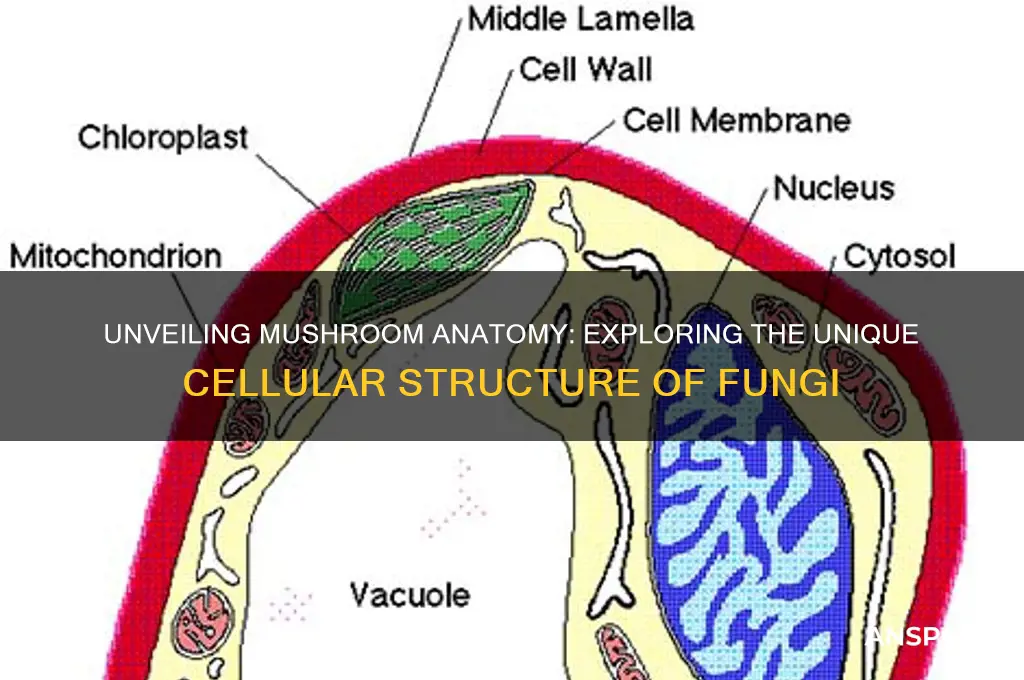

Mushrooms, often mistaken for plants, are actually fungi and are composed of unique cellular structures distinct from both plants and animals. Unlike plant cells, which have rigid cell walls made of cellulose, mushroom cells have walls primarily composed of chitin, a tough, flexible polysaccharide also found in the exoskeletons of insects and crustaceans. These cells are eukaryotic, meaning they contain a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles, but they lack chloroplasts, which is why mushrooms cannot photosynthesize. Instead, mushrooms obtain nutrients by absorbing organic matter from their environment through a network of thread-like structures called hyphae, which collectively form the mycelium. Understanding the cellular composition of mushrooms not only highlights their biological uniqueness but also sheds light on their ecological roles as decomposers and their potential applications in medicine, food, and biotechnology.

Explore related products

$11.99

What You'll Learn

- Hyphal Structure: Mushrooms are composed of thread-like cells called hyphae, forming a network called mycelium

- Cell Wall Composition: Fungal cells have chitin-based walls, unlike plants (cellulose) or animals (no walls)

- Multinucleate Cells: Some mushroom cells contain multiple nuclei, a unique fungal characteristic

- Spores as Cells: Mushroom spores are single cells dispersed for reproduction and colonization

- Vacuoles and Organelles: Fungal cells contain large vacuoles and specialized organelles for nutrient storage and metabolism

Hyphal Structure: Mushrooms are composed of thread-like cells called hyphae, forming a network called mycelium

Mushrooms, unlike plants and animals, are composed of unique cellular structures that define their growth and function. At the core of their composition are thread-like cells called hyphae, which are the fundamental building blocks of fungal organisms. These hyphae are long, slender, and tubular, typically ranging from 2 to 10 micrometers in diameter and growing to several centimeters in length. Each hypha is enclosed by a cell wall, primarily made of chitin, a tough polysaccharide that provides structural support and protection. This chitinous wall distinguishes fungal cells from those of plants (which have cell walls made of cellulose) and animals (which lack cell walls entirely).

Hyphae do not exist in isolation but instead form an intricate, interconnected network called mycelium. This mycelial network is the vegetative part of the fungus and serves as the primary mode of nutrient absorption and growth. As hyphae branch and extend through their substrate (such as soil or decaying matter), they secrete enzymes to break down complex organic materials into simpler compounds, which are then absorbed directly through the hyphal walls. This efficient nutrient acquisition system allows fungi to thrive in diverse environments, from forest floors to decaying logs. The mycelium is often hidden from view, with the mushroom itself being only the fruiting body that emerges under specific conditions to release spores for reproduction.

The structure of hyphae is both simple and highly efficient. Each hypha is typically divided into compartments by cross-walls called septa, which contain pores large enough to allow the flow of cytoplasm, nutrients, and organelles between cells. This interconnectedness ensures that resources are distributed evenly throughout the mycelium. However, not all hyphae are septate; some fungi have coenocytic hyphae, which lack septa and consist of continuous, multinucleate cytoplasm. The presence or absence of septa is a key characteristic used in fungal classification.

The hyphal structure also plays a critical role in the mushroom's ability to adapt and survive. Hyphae can grow rapidly, allowing the mycelium to explore new areas for nutrients. Additionally, the network can repair itself if damaged, as hyphae can regenerate and reconnect. This resilience is one reason fungi are among the most successful decomposers in ecosystems, breaking down tough materials like lignin and cellulose that other organisms cannot. The hyphal network's ability to form symbiotic relationships, such as mycorrhizae with plant roots, further highlights its ecological importance.

In summary, the hyphal structure is the foundation of mushroom anatomy, with thread-like hyphae forming the mycelium—a dynamic, nutrient-absorbing network. This structure not only defines the physical characteristics of fungi but also underpins their ecological roles as decomposers, symbionts, and recyclers of organic matter. Understanding hyphae and mycelium is essential to grasping how mushrooms function and thrive in their environments.

Reishi Mushrooms: HSV2 Treatment?

You may want to see also

Cell Wall Composition: Fungal cells have chitin-based walls, unlike plants (cellulose) or animals (no walls)

Mushrooms, like all fungi, are composed of cells that have a unique structure compared to plants and animals. One of the most distinctive features of fungal cells is their cell wall composition. Unlike plant cells, which have cell walls made of cellulose, and animal cells, which lack cell walls entirely, fungal cells possess cell walls primarily composed of chitin. Chitin is a complex carbohydrate and a derivative of glucose, providing structural support and protection to the fungal cell. This chitin-based cell wall is a defining characteristic of fungi and plays a crucial role in their survival and function.

The presence of chitin in fungal cell walls sets mushrooms apart from other organisms. Chitin is a tough, yet flexible polymer that forms a robust barrier around the cell, protecting it from mechanical stress and environmental threats. This composition is particularly important for mushrooms, as they often grow in diverse and challenging environments, such as decaying wood or soil. The chitin-based cell wall allows fungal cells to maintain their shape and integrity while adapting to their surroundings. In contrast, cellulose in plant cell walls provides rigidity but lacks the flexibility that chitin offers.

Another key aspect of the chitin-based cell wall in mushrooms is its role in fungal growth and development. Chitin acts as a scaffold for the cell, enabling it to expand and divide while maintaining structural stability. During the growth of mushrooms, the cell wall must be dynamically remodeled to accommodate increases in cell size and changes in shape. Chitin’s unique properties allow for this remodeling, ensuring that the cell wall remains intact and functional throughout the mushroom’s life cycle. This is in stark contrast to animal cells, which rely on the cytoskeleton for shape and movement in the absence of a cell wall.

The chitin-based cell wall also has implications for how mushrooms interact with their environment. For example, chitin is resistant to degradation by many enzymes found in other organisms, which helps protect fungal cells from predation and competition. However, certain organisms, such as bacteria and some insects, produce enzymes called chitinases that can break down chitin, highlighting the complex ecological interactions involving mushrooms. This resistance to degradation is one reason why fungi, including mushrooms, are successful decomposers in ecosystems, breaking down organic matter that other organisms cannot.

In summary, the cell walls of mushrooms are composed of chitin, a feature that distinguishes them from plants (cellulose-based walls) and animals (no cell walls). This chitin-based composition provides structural support, flexibility, and protection, enabling mushrooms to thrive in diverse environments. Understanding the unique cell wall composition of fungal cells is essential for appreciating the biology and ecological roles of mushrooms, as well as for applications in fields such as medicine, agriculture, and biotechnology.

Mushrooms and Onions: A Flavorful Match Made in Culinary Heaven?

You may want to see also

Multinucleate Cells: Some mushroom cells contain multiple nuclei, a unique fungal characteristic

Mushrooms, like all fungi, are composed of cells that differ significantly from those of plants and animals. One of the most fascinating aspects of fungal cells is their ability to be multinucleate, meaning some cells contain multiple nuclei within a single cell wall. This characteristic is particularly prominent in certain mushroom species and is a defining feature of fungal biology. Unlike animal and plant cells, which are typically uninucleate (containing one nucleus), multinucleate cells in mushrooms allow for complex genetic interactions and efficient resource distribution within the cell.

The presence of multinucleate cells in mushrooms is a result of their unique life cycle and growth patterns. During the vegetative growth phase, fungal hyphae (thread-like structures that make up the mushroom's body) often undergo nuclear division without cytoplasmic division, a process known as syncytial growth. This results in long, continuous hyphae filled with multiple nuclei. In some cases, these hyphae can fuse together, creating a network of interconnected cells with shared cytoplasm and nuclei, known as a coenocytic structure. This multinucleate condition enhances the mushroom's ability to adapt to its environment, as multiple nuclei can coordinate responses to stressors or nutrient availability.

Multinucleate cells in mushrooms also play a crucial role in their reproductive processes. For example, during the formation of fruiting bodies (the visible part of the mushroom), multinucleate cells differentiate into specialized structures like gills or pores, where spores are produced. The presence of multiple nuclei in these cells ensures efficient genetic recombination and spore development. Additionally, multinucleate cells contribute to the rapid growth and resilience of mushrooms, enabling them to colonize diverse habitats, from forest floors to decaying matter.

The uniqueness of multinucleate cells in mushrooms lies in their contrast to the cellular organization of other eukaryotes. While some organisms, like skeletal muscle cells in animals, exhibit multinucleation, this trait is far more widespread and integral to fungal biology. The ability of mushroom cells to maintain multiple nuclei within a single cell wall highlights the evolutionary innovations of fungi, allowing them to thrive in environments where other organisms struggle. This characteristic is not just a curiosity but a key to understanding the ecological success and diversity of mushrooms.

In summary, multinucleate cells are a hallmark of mushroom biology, reflecting the unique cellular organization and life strategies of fungi. These cells, containing multiple nuclei within a shared cytoplasm, enable efficient growth, resource allocation, and reproductive success. By studying multinucleate cells, scientists gain insights into the fundamental differences between fungal, plant, and animal cells, underscoring the remarkable adaptability and complexity of mushrooms in the natural world.

White Mushrooms: Delicious or Bland?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spores as Cells: Mushroom spores are single cells dispersed for reproduction and colonization

Mushroom spores are a fascinating example of how fungi utilize single cells for reproduction and colonization. Unlike plants and animals, which are composed of multicellular structures, mushrooms and other fungi are primarily made up of thread-like structures called hyphae. However, spores represent a unique cellular form in the fungal life cycle. Each spore is a single, self-contained cell designed to survive harsh conditions and disperse over long distances. This cellular simplicity allows spores to function as both a reproductive unit and a means of colonization, ensuring the survival and spread of the fungal species.

As single cells, mushroom spores are remarkably resilient. They are equipped with a thick cell wall composed of chitin, a durable polysaccharide that protects the spore from desiccation, UV radiation, and other environmental stressors. This protective layer is essential for the spore’s longevity, enabling it to remain dormant for extended periods until conditions are favorable for germination. Inside the spore, the cytoplasm contains the genetic material necessary for growth, encapsulated within a nucleus. This compact cellular structure ensures that the spore can carry all the information required to develop into a new fungal organism when activated.

The dispersal of spores as single cells is a critical strategy for fungal reproduction and colonization. Mushrooms release spores into the environment through various mechanisms, such as wind, water, or animals. Once released, these single cells can travel vast distances, increasing the chances of finding new habitats. Upon landing in a suitable environment with adequate moisture, nutrients, and temperature, the spore germinates, forming a hypha that grows into a network of hyphae, ultimately developing into a new mushroom. This process highlights the dual role of spores as both reproductive agents and pioneers of colonization.

Spores also exhibit remarkable adaptability as single cells. They can remain viable in diverse environments, from soil and decaying matter to extreme conditions like deserts or high altitudes. This adaptability is due to their ability to enter a state of dormancy, reducing metabolic activity to conserve energy. When conditions improve, the spore reactivates, initiating growth. This cellular flexibility ensures that fungi can thrive in a wide range of ecosystems, making them one of the most successful groups of organisms on Earth.

In summary, mushroom spores are single cells that play a pivotal role in fungal reproduction and colonization. Their simple yet robust cellular structure, combined with their resilience and adaptability, enables them to disperse widely and establish new fungal growth in diverse environments. Understanding spores as cells provides insight into the unique biology of mushrooms and their ability to thrive in virtually every corner of the planet. This perspective underscores the importance of cellular specialization in the fungal life cycle and its contribution to the ecological success of mushrooms.

Matsutake Mushrooms: A Forager's Treasure

You may want to see also

Vacuoles and Organelles: Fungal cells contain large vacuoles and specialized organelles for nutrient storage and metabolism

Mushrooms, like all fungi, are composed of eukaryotic cells, which are characterized by their complex internal organization and membrane-bound organelles. One of the most striking features of fungal cells, including those of mushrooms, is the presence of large vacuoles. These vacuoles are dynamic, fluid-filled compartments that play a crucial role in maintaining cell turgor pressure, storing nutrients, and detoxifying harmful substances. In mushrooms, vacuoles can occupy a significant portion of the cell volume, acting as reservoirs for ions, sugars, and secondary metabolites that are essential for growth and survival. Their ability to expand and contract allows fungal cells to adapt to varying environmental conditions, such as changes in water availability or nutrient levels.

In addition to vacuoles, fungal cells contain specialized organelles that support nutrient storage and metabolism. For instance, mitochondria are vital for energy production through cellular respiration, enabling mushrooms to break down stored nutrients like carbohydrates and lipids to fuel their growth and development. Another critical organelle is the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), which is involved in protein synthesis and lipid metabolism. The ER works in conjunction with the Golgi apparatus, which modifies, sorts, and packages proteins and lipids for transport to their final destinations within or outside the cell. These organelles ensure that mushrooms can efficiently process and utilize the nutrients they absorb from their environment.

Fungal cells also possess lysosomes, which are specialized organelles containing digestive enzymes. Lysosomes break down complex molecules, such as proteins and polysaccharides, into simpler forms that can be reused by the cell. This process is particularly important for saprotrophic fungi, including many mushroom species, which obtain nutrients by decomposing organic matter. Additionally, peroxisomes are present in fungal cells, playing a role in detoxification and the breakdown of fatty acids. These organelles work together to maintain cellular homeostasis and support the metabolic demands of mushroom growth.

The cell wall of fungal cells, including mushrooms, is another critical structure composed primarily of chitin, glucans, and other polysaccharides. While not an organelle, the cell wall is essential for nutrient storage and metabolism, as it provides structural support and protects the cell from environmental stresses. It also houses enzymes that facilitate the breakdown of external nutrients, which are then transported into the cell for storage or metabolic use. The interplay between the cell wall and internal organelles highlights the integrated nature of fungal cellular functions.

In summary, the large vacuoles and specialized organelles in fungal cells, such as those found in mushrooms, are key to their ability to store nutrients and maintain metabolic activities. Vacuoles serve as versatile storage compartments, while organelles like mitochondria, the ER, Golgi apparatus, lysosomes, and peroxisomes work in concert to process and utilize nutrients efficiently. Together, these cellular components enable mushrooms to thrive in diverse environments, from forest floors to decomposing organic matter, by optimizing their nutrient storage and metabolic capabilities.

Cleaning Fresh Shiitake Mushrooms: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mushrooms are made of eukaryotic cells, which are complex cells with a nucleus and membrane-bound organelles.

No, mushrooms do not have plant cells. They belong to the kingdom Fungi and have fungal cells, which lack chlorophyll and cell walls made of chitin, not cellulose.

Mushroom cells are part of a multicellular structure. The main body of a mushroom (the fruiting body) is composed of many fungal cells working together.

The cell wall of a mushroom is primarily made of chitin, a tough polysaccharide, unlike plant cell walls, which are made of cellulose.

Yes, mushroom cells are eukaryotic, meaning they contain a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles, similar to animal and plant cells.