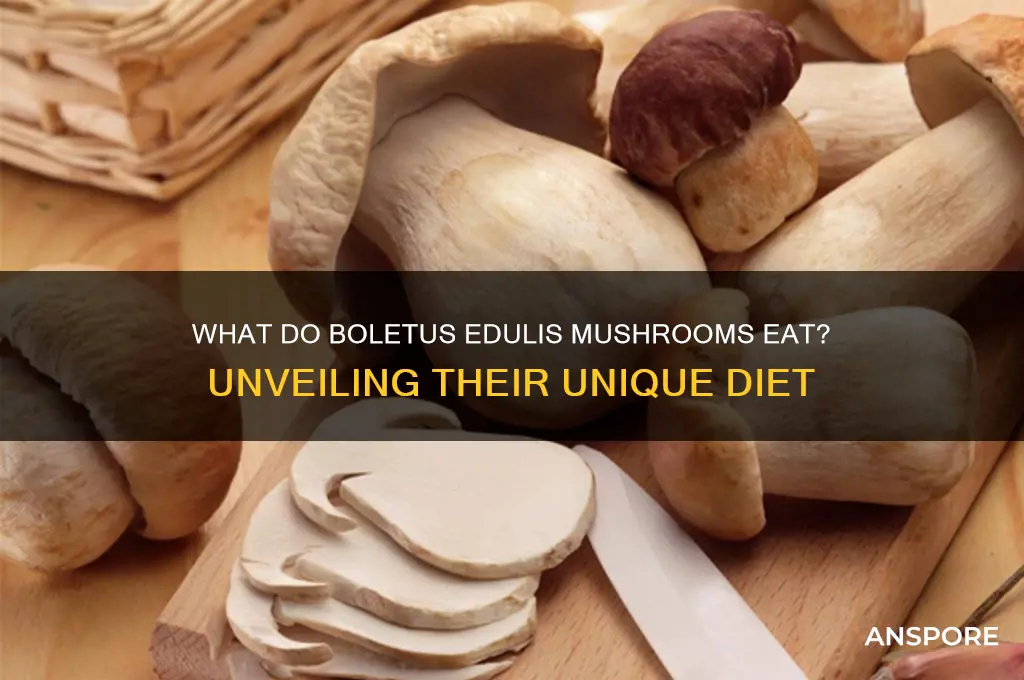

Boletus edulis, commonly known as the porcini or cep mushroom, is a highly prized edible fungus found in various parts of the world, particularly in Europe and North America. Unlike animals, mushrooms do not eat in the traditional sense; instead, they obtain nutrients through a process called mycorrhizal association. Boletus edulis forms a symbiotic relationship with the roots of trees, primarily conifers and deciduous species like oak, beech, and pine. In this relationship, the mushroom absorbs nutrients such as sugars produced by the tree through photosynthesis, while the tree benefits from the mushroom's extensive mycelial network, which enhances its ability to absorb water and minerals from the soil. This mutualistic partnership is essential for the growth and survival of both the mushroom and its host tree.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Mycorrhizal Relationships: Boletus edulis forms symbiotic partnerships with tree roots for nutrients

- Soil Nutrient Absorption: Extracts minerals and organic matter from forest soil

- Tree Sugar Exchange: Receives sugars from trees in exchange for water and nutrients

- Decomposition Role: Helps break down organic debris in its ecosystem

- Forest Ecosystem Contribution: Supports nutrient cycling and tree health in woodlands

Mycorrhizal Relationships: Boletus edulis forms symbiotic partnerships with tree roots for nutrients

Boletus edulis, commonly known as the porcini or cep mushroom, does not "eat" in the traditional sense as animals do. Instead, it forms intricate and mutually beneficial relationships with the roots of trees through a process called mycorrhization. This symbiotic partnership is fundamental to the nutrition and survival of both the mushroom and its host tree. Mycorrhizal relationships are a cornerstone of forest ecosystems, facilitating the exchange of nutrients and enhancing the health and resilience of both fungi and plants.

In this mycorrhizal relationship, Boletus edulis fungi colonize the roots of trees, primarily conifers and deciduous species like oak, beech, and pine. The fungus extends its network of thread-like structures called hyphae into the soil, significantly increasing the surface area available for nutrient absorption. Trees often struggle to access essential nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen directly from the soil, especially in nutrient-poor environments. The hyphae of Boletus edulis act as an extension of the tree’s root system, efficiently extracting these nutrients and delivering them to the tree.

In return for this service, the tree provides the fungus with carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis. Since fungi cannot photosynthesize, they rely on their host plants for this vital energy source. This exchange ensures that both organisms thrive: the tree gains access to hard-to-reach nutrients, while the fungus receives the energy it needs to grow and reproduce. This interdependence highlights the elegance and efficiency of mycorrhizal relationships in nature.

The mycorrhizal network formed by Boletus edulis also plays a critical role in soil health and ecosystem stability. The fungal hyphae bind soil particles together, improving soil structure and water retention. Additionally, these networks can connect multiple trees, facilitating the transfer of nutrients and signals between them. This underground web of life enhances the overall resilience of the forest, enabling trees to better withstand stressors like drought, disease, and nutrient deficiencies.

Understanding the mycorrhizal relationships of Boletus edulis is not only crucial for appreciating its ecological role but also for cultivating this prized edible mushroom. Efforts to grow porcini mushrooms commercially often involve inoculating tree roots with the fungus, mimicking its natural habitat. By fostering these symbiotic partnerships, both forest ecosystems and human cultivators can benefit from the remarkable abilities of Boletus edulis to access and share nutrients in the soil. This intricate dance between fungus and tree underscores the interconnectedness of life in forest ecosystems.

Mushrooms and Gastritis: Safe to Eat or Best Avoided?

You may want to see also

Soil Nutrient Absorption: Extracts minerals and organic matter from forest soil

Boletus edulis, commonly known as the porcini or cep mushroom, is a mycorrhizal fungus that forms symbiotic relationships with the roots of trees. This relationship is fundamental to its ability to extract nutrients from forest soil. Unlike saprophytic fungi that decompose dead organic matter, B. edulis relies on living tree partners to access essential resources. Through its extensive mycelial network, the fungus absorbs minerals and organic compounds directly from the soil, which are then shared with the host tree in exchange for carbohydrates produced via photosynthesis.

The mycelium of Boletus edulis is highly efficient at breaking down complex soil components into usable forms. It secretes enzymes that degrade organic matter, such as fallen leaves, wood debris, and humus, releasing nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. These minerals are critical for the mushroom's growth and are also transferred to the host tree, enhancing its health and resilience. This process not only benefits the fungus and tree but also contributes to nutrient cycling within the forest ecosystem.

In addition to organic matter, Boletus edulis is particularly adept at extracting trace minerals from the soil, including calcium, magnesium, and iron. These minerals are often bound in insoluble forms but are made accessible by the fungus's enzymatic activity. The mycelium's ability to solubilize these nutrients is crucial for both the mushroom's development and the overall fertility of the forest soil. This mineral extraction process ensures that essential elements are not locked away but are actively circulated within the ecosystem.

The fungus's role in soil nutrient absorption extends beyond its immediate needs. By improving soil structure and enhancing nutrient availability, Boletus edulis indirectly supports a wide range of forest organisms. Its mycelial network acts as a conduit for water and nutrients, facilitating their movement through the soil profile. This not only aids the host tree but also benefits neighboring plants and microorganisms, fostering a more robust and diverse forest environment.

Understanding how Boletus edulis extracts minerals and organic matter from forest soil highlights its ecological significance. This process underscores the mushroom's role as a keystone species in forest ecosystems, where it bridges the gap between soil resources and plant nutrition. For foragers and cultivators, recognizing the fungus's reliance on specific soil conditions can inform sustainable harvesting practices and cultivation techniques, ensuring the long-term health of both the mushroom and its forest habitat.

In summary, the nutrient absorption capabilities of Boletus edulis are a testament to its adaptability and importance in forest ecosystems. By extracting minerals and organic matter from the soil, it not only sustains itself and its host tree but also contributes to the overall vitality of the forest. This intricate process exemplifies the interconnectedness of life in woodland environments and emphasizes the need to protect these delicate relationships.

Did Jesus Eat Mushrooms? Exploring Ancient Texts and Theories

You may want to see also

Tree Sugar Exchange: Receives sugars from trees in exchange for water and nutrients

Boletus edulis, commonly known as the porcini or cep mushroom, forms a fascinating and mutually beneficial relationship with trees through a process called mycorrhizal association. In this symbiotic partnership, the mushroom does not "eat" in the traditional sense but rather engages in a sophisticated exchange of resources with its host tree. The key to this relationship is the Tree Sugar Exchange, where the mushroom receives sugars from the tree in return for essential water and nutrients. This exchange is fundamental to the survival and growth of both the mushroom and the tree.

The process begins with the mycelium—the underground network of fungal threads—of Boletus edulis wrapping around the roots of trees, primarily conifers and deciduous species like oak, beech, and pine. Trees produce sugars through photosynthesis, a process that converts sunlight, carbon dioxide, and water into glucose. However, trees often struggle to absorb water and nutrients efficiently from the soil, especially in nutrient-poor environments. This is where Boletus edulis steps in. The mycelium extends far beyond the tree's root system, increasing the surface area available for absorption. In exchange for the sugars provided by the tree, the mushroom delivers water and minerals such as phosphorus, nitrogen, and micronutrients, which it extracts from the soil.

The sugars received from the tree are vital for the growth and reproduction of Boletus edulis. These sugars serve as the primary energy source for the fungus, fueling its metabolic processes and enabling the production of fruiting bodies—the mushrooms we see above ground. Without this sugar exchange, the fungus would lack the energy needed to thrive and reproduce. Similarly, the tree benefits significantly from this partnership, as the enhanced nutrient and water uptake provided by the mycelium improves its overall health and resilience, particularly in challenging environments.

This sugar-for-nutrients exchange is not a one-time transaction but a continuous, dynamic process. The mycelium actively adjusts its activity based on the tree's needs and environmental conditions, ensuring a balanced and sustainable relationship. For example, during dry periods, the fungus may prioritize water absorption to support the tree, while in nutrient-poor soils, it focuses on mining minerals. This adaptability makes the mycorrhizal association between Boletus edulis and trees a highly efficient and resilient ecological interaction.

Understanding the Tree Sugar Exchange highlights the intricate interdependence between fungi and plants in forest ecosystems. Boletus edulis does not "eat" trees but rather participates in a sophisticated barter system where sugars are traded for water and nutrients. This relationship underscores the importance of mycorrhizal fungi in nutrient cycling and ecosystem health, demonstrating how cooperation at the microbial level supports the flourishing of entire forests. By studying this exchange, we gain insights into the hidden networks that sustain life beneath our feet.

Slime After Baking: Safe to Eat Mushrooms or Toss?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Decomposition Role: Helps break down organic debris in its ecosystem

Boletus edulis, commonly known as the porcini or cep mushroom, plays a crucial role in its ecosystem as a decomposer. Unlike plants that produce their own food through photosynthesis, B. edulis obtains nutrients by breaking down organic matter in its environment. This process is essential for nutrient cycling in forests, where the mushroom thrives in symbiotic relationships with trees and other organic debris. By decomposing complex organic materials, B. edulis helps return vital nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon back into the soil, supporting the overall health of the ecosystem.

The primary food source for Boletus edulis is dead or decaying organic material, such as fallen leaves, wood, and plant litter. Its mycelium, a network of thread-like structures, secretes enzymes that break down cellulose, lignin, and other tough plant components into simpler compounds. This ability to decompose lignin, a complex polymer found in wood, is particularly significant, as few organisms can efficiently break it down. By targeting these hard-to-decompose materials, B. edulis accelerates the decomposition process, ensuring that nutrients are not locked away in dead plant matter for extended periods.

In addition to breaking down dead plant material, Boletus edulis also forms mycorrhizal associations with living tree roots. In this symbiotic relationship, the mushroom helps trees absorb water and nutrients from the soil, while the tree provides the mushroom with carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis. Even in this mutualistic role, B. edulis contributes to decomposition indirectly by enhancing the health and longevity of trees, whose fallen leaves and branches eventually become part of the forest floor’s organic debris.

The decomposition activity of Boletus edulis is not limited to its immediate surroundings. As the mycelium spreads through the soil, it creates pathways for nutrient transport, facilitating the movement of organic matter and minerals across the ecosystem. This network also improves soil structure, making it more porous and capable of retaining water, which further supports plant growth and microbial activity. By acting as both a decomposer and a facilitator of nutrient cycling, B. edulis plays a dual role in maintaining the balance of forest ecosystems.

Finally, the decomposition role of Boletus edulis has broader ecological implications. By breaking down organic debris, it prevents the accumulation of dead material, reducing the risk of disease and pest outbreaks in forests. This process also contributes to carbon sequestration, as decomposed organic matter is stored in the soil rather than released into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide. Thus, B. edulis not only sustains its own survival but also supports the resilience and productivity of the entire ecosystem through its decomposition activities.

Do Squirrels Eat Raw Mushrooms? Exploring Their Natural Diet Habits

You may want to see also

Forest Ecosystem Contribution: Supports nutrient cycling and tree health in woodlands

Boletus edulis, commonly known as the porcini or cep mushroom, plays a crucial role in forest ecosystems by forming symbiotic relationships with trees, a process known as mycorrhiza. In this relationship, the mushroom does not "eat" in the traditional sense but rather exchanges nutrients with its host tree. The tree provides carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis, while the mushroom’s extensive mycelial network absorbs essential nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and trace minerals from the soil. This mutualistic partnership is fundamental to the health and productivity of woodland ecosystems, as it enhances nutrient cycling and supports tree vitality.

One of the primary contributions of Boletus edulis to forest ecosystems is its ability to improve nutrient availability for trees. The mycelium of these mushrooms can access nutrients locked in organic matter and mineral forms that tree roots alone cannot efficiently utilize. By breaking down complex compounds and increasing nutrient uptake, the mushroom ensures that trees receive the elements necessary for growth and development. This process not only benefits individual trees but also strengthens the overall resilience of the forest, enabling it to better withstand environmental stressors such as drought or disease.

In addition to nutrient acquisition, Boletus edulis aids in soil structure improvement, which indirectly supports tree health. The mycelial network binds soil particles together, enhancing soil aggregation and porosity. This improves water retention and aeration, creating a more favorable environment for tree roots to grow and thrive. Healthy soil structure also promotes the activity of other beneficial microorganisms, further enriching the soil ecosystem and fostering a balanced nutrient cycle within the forest.

Another critical aspect of Boletus edulis’s role is its involvement in carbon sequestration. As part of the mycorrhizal network, the mushroom helps trees store carbon more efficiently by facilitating nutrient uptake and promoting robust tree growth. Larger, healthier trees can sequester greater amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, contributing to climate regulation. Thus, the presence of Boletus edulis in woodlands not only supports local ecosystem health but also has broader implications for global carbon dynamics.

Finally, the presence of Boletus edulis in a forest ecosystem can serve as an indicator of overall ecological health. These mushrooms thrive in well-balanced, undisturbed environments where trees and soil microorganisms coexist harmoniously. Their abundance reflects effective nutrient cycling and symbiotic relationships, signaling that the forest is functioning optimally. By studying and preserving Boletus edulis and its mycorrhizal associations, forest managers can ensure the long-term sustainability and productivity of woodland ecosystems, maintaining their vital contributions to both local and global ecosystems.

Do Moose Eat Mushrooms? Unveiling Their Unique Dietary Habits

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Boletus edulis mushrooms are mycorrhizal fungi, meaning they form a symbiotic relationship with the roots of trees. They do not "eat" in the traditional sense but instead obtain nutrients by exchanging minerals and water from the soil with carbohydrates produced by the tree through photosynthesis.

Unlike saprotrophic fungi that decompose dead organic matter, Boletus edulis does not break down or consume dead material. Instead, it relies on its mutualistic partnership with living tree roots to acquire nutrients.

No, Boletus edulis cannot survive without a host tree. Its mycorrhizal relationship is essential for its growth and nutrient acquisition, making it dependent on the presence of compatible tree species like oak, beech, or pine.