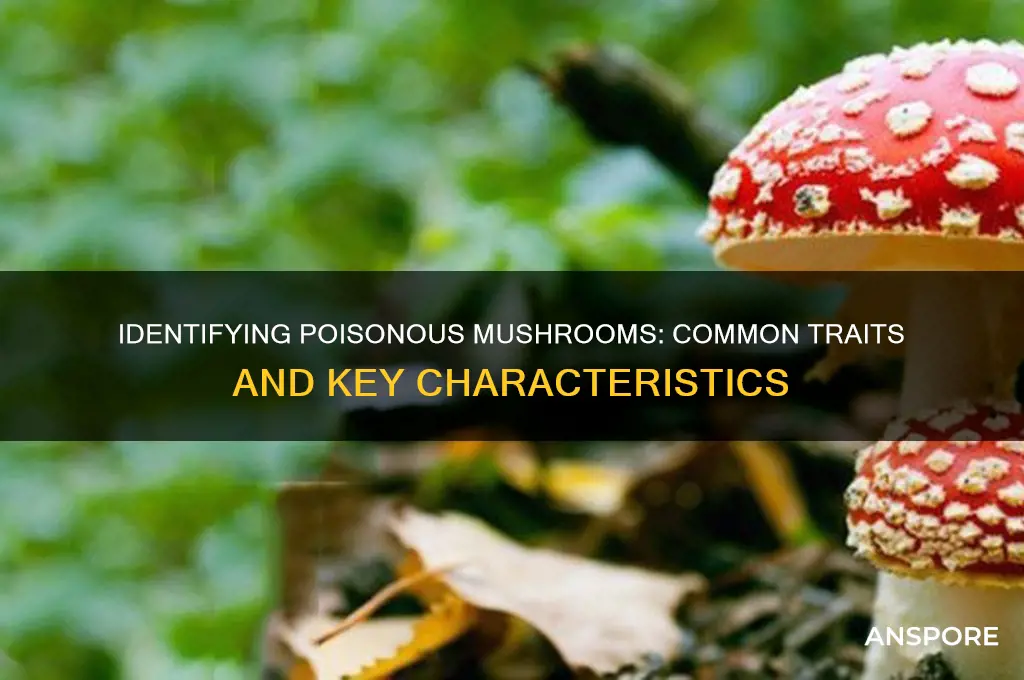

Poisonous mushrooms share several common characteristics that can aid in their identification, though it’s crucial to note that no single feature is foolproof. Many toxic species, such as the Amanita genus (e.g., the Death Cap and Destroying Angel), often have a distinctive cup-like structure at the base of the stem called a volva, which is a remnant of the universal veil. Additionally, they frequently possess a ring on the stem, known as an annulus, and white or colored spores that can be observed through spore prints. Some poisonous mushrooms also exhibit vivid or unusual colors, such as bright red, white, or green, though this is not exclusive to toxic varieties. While these traits can provide clues, accurate identification requires a combination of features, and consuming wild mushrooms without expert guidance is strongly discouraged due to the potential for severe toxicity or fatality.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Distinctive cap colors: Bright reds, whites, or yellows often signal toxicity in many mushroom species

- Gill and stem features: Unique patterns, colors, or structures can indicate poisonous varieties

- Spore print analysis: Toxic mushrooms often produce distinct spore colors when printed

- Habitat preferences: Poisonous species frequently grow near specific trees or in certain environments

- Presence of toxins: Common toxins like amatoxins or muscarine are shared among deadly mushrooms

Distinctive cap colors: Bright reds, whites, or yellows often signal toxicity in many mushroom species

Brightly colored mushrooms often serve as nature’s warning signs, with vivid reds, whites, and yellows frequently indicating toxicity. This phenomenon is not arbitrary; it’s an evolutionary strategy known as aposematism, where organisms develop striking colors to deter predators. For foragers, this means a mushroom’s cap color can be a critical first clue in identifying potential danger. While not all colorful mushrooms are poisonous, and not all poisonous mushrooms are colorful, this pattern is consistent enough to warrant caution. For instance, the Fly Agaric (*Amanita muscaria*), with its iconic red cap and white spots, is both famous and toxic, causing hallucinations and gastrointestinal distress if ingested.

When venturing into the woods, beginners should adopt a simple rule: avoid mushrooms with caps in these bright hues unless positively identified as safe. This doesn’t mean all red, white, or yellow mushrooms are off-limits—edible species like the Chanterelle (*Cantharellus cibarius*) have a golden hue—but it does mean thorough verification is essential. Field guides and mobile apps can aid in this process, but cross-referencing multiple sources is advisable. For families foraging with children, emphasize the "bright equals beware" rule, as kids are naturally drawn to colorful objects. Even touching certain toxic species can cause skin irritation, so gloves are a practical precaution.

The science behind these colors is as fascinating as it is practical. Pigments like carotenoids (yellows and reds) and anthraquinones (bright reds) often correlate with the presence of toxins. For example, the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*), notorious for its pale green or white cap, contains amatoxins that can cause liver failure in doses as small as half a mushroom cap. While its color is less vivid, it underscores the broader principle: unusual or striking coloration should always prompt suspicion. Advanced foragers might note exceptions, such as the edible Sulphur Tuft (*Hypholoma fasciculare*), which has a yellow cap but is easily distinguished by its green spore print—a reminder that color is just one piece of the identification puzzle.

Instructing novice foragers to focus on cap color is a practical starting point, but it’s equally important to stress its limitations. Toxicity can’t be determined by color alone; factors like gill structure, spore color, habitat, and seasonality must also be considered. For instance, the white caps of edible Oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) and the deadly Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*) look similar to the untrained eye but differ drastically in their gill attachment and spore characteristics. Always carry a knife for detailed examination and a basket to avoid damaging specimens. If in doubt, leave it out—no meal is worth the risk of poisoning.

Ultimately, the "bright cap" rule is a valuable heuristic, but it’s not foolproof. Education and experience are the best safeguards against accidental poisoning. Joining a local mycological society or attending foraging workshops can provide hands-on learning and mentorship. For those who prefer self-study, investing in a reputable field guide with detailed photographs and descriptions is essential. Remember, mushrooms don’t come with labels, and nature’s warnings are subtle but consistent. By respecting these cues and approaching foraging with caution, enthusiasts can safely explore the fascinating world of fungi without falling victim to its more dangerous inhabitants.

Are Shiitake Mushrooms Safe for Dogs? Risks and Facts

You may want to see also

Gill and stem features: Unique patterns, colors, or structures can indicate poisonous varieties

The gills and stem of a mushroom are like its fingerprint, offering subtle yet critical clues to its identity. Poisonous varieties often flaunt unique patterns, colors, or structures in these areas, serving as nature’s warning signs. For instance, the deadly Amanita species frequently display white gills and a bulbous stem base with a distinctive cup-like volva, a feature rarely seen in edible mushrooms. Observing these details can be the difference between a safe forage and a dangerous mistake.

Analyzing gill attachment is another key step in identification. Poisonous mushrooms like the Destroying Angel (Amanita bisporigera) often have gills that are free from the stem, meaning they do not attach directly to it. In contrast, many edible mushrooms, such as the common button mushroom (Agaricus bisporus), have gills that are attached or notched at the stem. This simple distinction can narrow down the possibilities significantly. Always carry a magnifying glass to inspect these minute features closely.

Coloration in gills and stems can also signal toxicity. For example, the gills of the Galerina marginata, a highly poisonous species often mistaken for edible mushrooms, turn rusty brown with age. Similarly, the stem of the Fly Agaric (Amanita muscaria), while iconic for its red cap with white dots, also exhibits a yellow or white stem that bruises easily. These color changes are not just aesthetic; they are biochemical indicators of toxins like amatoxins or ibotenic acid. If you notice unusual bruising, discoloration, or vibrant hues, proceed with extreme caution.

Structural anomalies in stems, such as partial veils or rings, are further red flags. Poisonous mushrooms like the Death Cap (Amanita phalloides) often have a membranous ring around the stem, a feature absent in most edible varieties. Additionally, a fragile, easily separable ring, as seen in the Conocybe filaris, is another warning sign. These structures are remnants of the mushroom’s developmental stages and can indicate the presence of toxins. Always document these features with photographs for later reference or expert consultation.

In practice, combining these observations with other identification methods, such as spore prints and habitat analysis, is essential. For beginners, avoid mushrooms with white gills, bulbous stem bases, or rings until you gain expertise. Remember, no single feature guarantees toxicity, but a cluster of suspicious traits should prompt you to err on the side of caution. When in doubt, consult a mycologist or a reliable field guide—your safety is not worth risking for a meal.

Is Lactarius Indigo Mushroom Poisonous? Facts and Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Spore print analysis: Toxic mushrooms often produce distinct spore colors when printed

Toxic mushrooms often leave behind a calling card in the form of their spore prints, a simple yet powerful tool for identification. By placing the cap of a mushroom, gills facing down, on a piece of paper or glass for several hours, you can capture the color of its spores. This method is particularly useful because spore color is a consistent characteristic, unlike features like cap shape or habitat, which can vary due to environmental factors. For instance, the deadly Amanita phalloides, responsible for the majority of mushroom-related fatalities, produces a striking white spore print, a detail that can be crucial in distinguishing it from less harmful lookalikes.

The process of creating a spore print is straightforward but requires patience and precision. Start by selecting a mature mushroom with well-developed gills or pores. Place the cap, gill-side down, on a piece of white paper for light-colored spores or black paper for dark spores. Cover the mushroom with a bowl or glass to maintain humidity and prevent air currents from dispersing the spores. After 2–24 hours, carefully lift the cap to reveal the spore deposit. The color of this print can range from white and cream to shades of brown, black, purple, or even green, each hue narrowing down the mushroom’s possible identity. For example, the toxic Galerina marginata produces a rust-brown spore print, a key feature that differentiates it from edible species like the common ink cap.

While spore print analysis is a valuable technique, it’s not without limitations. Some mushrooms, particularly those with thick or enclosed gills, may not release spores effectively. Additionally, spore color alone is not definitive for identification; it must be combined with other characteristics such as cap color, gill attachment, and habitat. However, when used correctly, spore prints can significantly reduce the margin of error. For instance, the toxic Cortinarius species often produce rusty-brown spore prints, a trait that, when paired with their web-like partial veil, makes them easier to identify and avoid.

For foragers and mycologists alike, understanding spore print analysis is a critical skill. It’s a non-destructive method that preserves the mushroom for further examination and can be performed with minimal equipment. Beginners should practice on common, easily identifiable species before attempting to analyze potentially toxic varieties. Always cross-reference spore print results with other field guides or expert advice, as misidentification can have severe consequences. By mastering this technique, you gain a reliable tool in the quest to distinguish between harmless and harmful fungi, ensuring safer foraging practices.

Toxic Fungi Impact: Understanding Poisonous Mushroom Effects on the Body

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Habitat preferences: Poisonous species frequently grow near specific trees or in certain environments

Poisonous mushrooms often exhibit a striking affinity for particular habitats, a trait that can serve as a crucial identifier for foragers and enthusiasts alike. One notable pattern is their tendency to flourish in the vicinity of specific tree species. For instance, the deadly Amanita phalloides, commonly known as the Death Cap, is frequently found under oak trees, forming a symbiotic relationship with their roots. This mycorrhizal association is not unique to poisonous species, but certain toxic mushrooms have a distinct preference for particular tree partners. The presence of these trees can act as a warning sign, prompting a closer inspection of the surrounding fungal growth.

A Walk in the Woods: Identifying Hotspots

Imagine strolling through a forest, where the dappled sunlight filters through the canopy above. You notice a cluster of mushrooms sprouting at the base of a beech tree. This scenario is not uncommon, as many poisonous mushrooms, such as the Amanita genus, are often found in deciduous woodlands, particularly those with beech, oak, and birch trees. These trees provide the ideal environment for mycorrhizal fungi, which form a mutualistic relationship with the tree roots, exchanging nutrients for carbohydrates. While not all mushrooms in these areas are toxic, the presence of specific tree species can indicate a higher likelihood of encountering poisonous varieties.

The Environmental Factor: Uncovering Hidden Dangers

Habitat preferences of poisonous mushrooms extend beyond tree associations. Certain toxic species thrive in specific environmental conditions, which can be a critical aspect of their identification. For example, the poisonous Galerina marginata, often mistaken for edible species, favors decaying wood, especially conifer stumps and logs. This preference for lignin-rich environments is a key characteristic that distinguishes it from similar-looking edible mushrooms. Understanding these habitat nuances can be a powerful tool for foragers, helping them make informed decisions when collecting mushrooms.

In practical terms, this knowledge can be applied as a precautionary measure. When foraging, pay close attention to the substrate on which mushrooms grow. Are they emerging from the soil, wood, or perhaps even animal dung? Each of these habitats may be indicative of specific mushroom species, some of which could be toxic. For instance, the poisonous Panaeolus species are often found in grassy areas enriched with animal manure, a habitat that should prompt caution. By recognizing these environmental cues, foragers can significantly reduce the risk of accidental poisoning.

A Word of Caution: Look-Alikes and Misidentification

It is essential to emphasize that while habitat preferences provide valuable clues, they should not be the sole basis for identification. Many poisonous mushrooms have non-toxic look-alikes that share similar habitats. The infamous Amanita muscaria, with its bright red cap and white spots, often grows in coniferous and deciduous forests, just like many edible species. Misidentification can have severe consequences, as some toxic mushrooms contain potent toxins like amatoxins, which can cause severe liver damage, even in small doses. Therefore, a comprehensive approach to identification, considering multiple characteristics, is imperative.

In summary, understanding the habitat preferences of poisonous mushrooms is a vital skill for anyone venturing into the world of mycology. By recognizing the specific trees and environments these fungi favor, foragers can make more informed decisions, reducing the risk of accidental poisoning. However, this knowledge should be coupled with a thorough understanding of other identifying features, ensuring a safe and enjoyable mushroom-hunting experience.

Red and White Mushrooms: Are They Poisonous or Safe to Eat?

You may want to see also

Presence of toxins: Common toxins like amatoxins or muscarine are shared among deadly mushrooms

Poisonous mushrooms share a sinister secret: their toxicity often stems from specific chemical compounds, with amatoxins and muscarine being two of the most notorious. These toxins are not unique to a single species but are found across various deadly mushrooms, making them a critical factor in identifying potential threats. Amatoxins, for instance, are cyclic octapeptides primarily found in the Amanita genus, including the infamous Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) and Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*). Even a small amount—as little as half a mushroom—can cause severe liver and kidney damage, leading to organ failure and death within days if left untreated.

Muscarine, another common toxin, is named after the mushroom genus *Clitocybe* but is also present in species like the Inocybe mushrooms. Unlike amatoxins, muscarine acts on the nervous system, causing symptoms such as excessive sweating, salivation, and blurred vision. While muscarine poisoning is rarely fatal, it can be extremely uncomfortable and requires immediate medical attention. The presence of these toxins highlights a critical point: identifying poisonous mushrooms isn’t just about recognizing physical traits but understanding the invisible dangers they carry.

To protect yourself, it’s essential to know that these toxins are heat-stable, meaning cooking or drying the mushrooms does not eliminate their toxicity. For example, amatoxins remain lethal even after boiling, and muscarine retains its effects regardless of preparation. This debunks the myth that poisonous mushrooms can be made safe by cooking. Instead, focus on accurate identification: avoid wild mushrooms unless you are absolutely certain of their species, and consult a mycologist or field guide when in doubt.

Practical tips include teaching children and pets to avoid touching or ingesting wild mushrooms, as even small exposures can be dangerous. If you suspect poisoning, seek medical help immediately and, if possible, bring a sample of the mushroom for identification. Time is critical, especially with amatoxin poisoning, where symptoms may not appear until 6–24 hours after ingestion, creating a false sense of safety. Understanding these toxins not only aids in identification but also emphasizes the importance of caution in the wild.

In summary, the presence of toxins like amatoxins and muscarine is a defining feature of many poisonous mushrooms. Their widespread occurrence across species, combined with their potency and resistance to common cooking methods, underscores the need for vigilance. By recognizing the risks and taking proactive steps, you can enjoy the beauty of fungi without falling victim to their hidden dangers.

Are Shrooms Poisonous? Uncovering the Truth About Magic Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Poisonous mushrooms often share traits like bright or unusual colors (e.g., red, white, or green), a bulbous or sac-like base, a ring on the stem, and gills that are closely spaced or forked. However, these features are not exclusive to toxic species, so caution is always advised.

While some poisonous mushrooms may have a strong, unpleasant odor or bitter taste, relying on smell or taste to identify toxicity is extremely dangerous. Many toxic species are odorless or taste pleasant, making this method unreliable for identification.

Poisonous mushrooms can grow in a variety of habitats, similar to edible ones. They are often found in forests, grasslands, and even urban areas. There is no specific habitat that guarantees the presence or absence of toxic species, so proper identification is crucial.