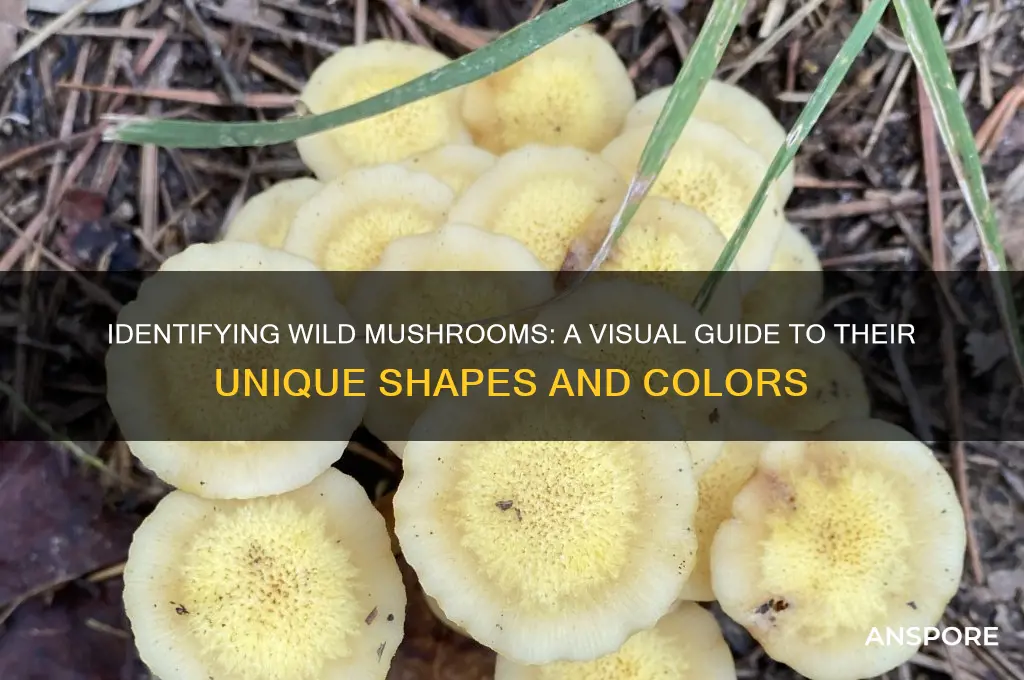

Wild mushrooms exhibit a diverse range of shapes, colors, and textures, making them a fascinating subject for nature enthusiasts and foragers alike. From the iconic red-and-white caps of the fly agaric (*Amanita muscaria*) to the delicate, fan-like gills of the oyster mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), each species has unique characteristics. Some, like the chanterelle, boast wavy, golden caps with forked gills, while others, such as the puffball, start as round, white orbs before releasing spores. Sizes vary dramatically, from tiny, cup-like fairy ring mushrooms to towering, tree-like clusters of lion's mane. Despite their beauty, it’s crucial to approach wild mushrooms with caution, as many are toxic or deadly, and accurate identification is essential.

Explore related products

$7.62 $14.95

What You'll Learn

- Cap shapes: convex, flat, or conical, often with unique textures and colors

- Gills: underside structures, varying in color, spacing, and attachment to the stem

- Stems: size, thickness, and presence of rings or bulbs at the base

- Colors: ranging from white and brown to vibrant reds, blues, and greens

- Textures: smooth, scaly, slimy, or fibrous surfaces on caps and stems

Cap shapes: convex, flat, or conical, often with unique textures and colors

Wild mushrooms exhibit a fascinating diversity in cap shapes, which are key characteristics for identification. Convex caps are among the most common, resembling a rounded dome that curves outward from the center. This shape is often seen in species like the meadow mushroom (*Agaricus campestris*), where the cap starts as a tight bud and expands into a broad, arched surface. Convex caps can vary in texture, ranging from smooth and silky to slightly viscid or even scaly, depending on the species. Colors also vary widely, from pure white and creamy hues to earthy browns, yellows, or even vibrant reds.

Flat caps, or planar caps, are another distinctive shape found in many wild mushrooms. These caps appear as if they have fully expanded and flattened out, often with a slightly depressed center or a shallow funnel-like shape. An example is the birch bolete (*Leccinum scabrum*), which features a broad, flat cap with a velvety texture. Flat caps may also exhibit unique patterns, such as radial streaks, patches of color, or a mottled appearance. Their colors can range from muted grays and greens to rich browns and oranges, often blending seamlessly with their forest habitats.

Conical caps are less common but equally striking, tapering to a distinct point at the center. This shape is characteristic of species like the witch's hat (*Hygrocybe conica*), which has a bright scarlet or orange conical cap with a matte or slightly slimy texture. Conical caps often retain their shape throughout the mushroom's life cycle, though some may flatten slightly with age. Their textures can be smooth, ribbed, or even hairy, adding to their visual appeal. Colors are often bold and eye-catching, making conical-capped mushrooms stand out in their surroundings.

Beyond these primary shapes, many wild mushrooms exhibit unique textures and colors that further distinguish them. For instance, some convex caps may have a velvety or felt-like texture, while others might be slimy or sticky to the touch. Flat caps can display intricate patterns, such as fibrous scales or a cracked appearance, as seen in the shaggy mane (*Coprinus comatus*). Conical caps might feature radial grooves or a powdery coating, enhancing their tactile and visual complexity. Colors can be just as varied, with gradients, streaks, or contrasting edges that serve as additional identification markers.

Understanding cap shapes and their associated textures and colors is essential for both mushroom enthusiasts and foragers. While convex, flat, and conical caps are the most prevalent, intermediate forms and variations are common, reflecting the adaptability and diversity of fungi. Observing these features closely, along with other characteristics like gills, spores, and habitat, can help accurately identify wild mushrooms and appreciate their natural beauty. Always remember, however, that proper identification is crucial, as some mushrooms can be toxic or even deadly.

Mastering Mushroom Cultivation: A Step-by-Step Guide to Growing Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Gills: underside structures, varying in color, spacing, and attachment to the stem

When identifying wild mushrooms, one of the most critical features to examine is the gills, which are the underside structures found on the cap of many mushroom species. Gills serve as the primary site for spore production and dispersal, making them a key characteristic for classification. They vary widely in appearance, including color, spacing, and attachment to the stem, each of which can provide valuable clues about the mushroom's identity. Observing these details carefully is essential for both amateur foragers and experienced mycologists.

Color is one of the most noticeable aspects of gills. Depending on the species, gills can range from pale white or cream to vibrant shades of pink, purple, brown, or even black. For example, the gills of the common *Agaricus* species are often pink when young, turning brown as they mature. In contrast, the gills of the *Amanita muscaria* are white, while those of the *Cortinarius* species can be purple or rusty brown. The color of the gills can change as the mushroom ages, so noting the stage of development is important. Some mushrooms also have gills that bruise or change color when touched, which can be a diagnostic feature.

The spacing of the gills is another crucial characteristic. Gills can be closely packed together, creating a nearly continuous surface, or they can be widely spaced, allowing light to pass through. For instance, the gills of the *Boletus* genus are typically widely spaced, while those of the *Marasmius* genus are often closely crowded. The spacing can also be described as "distant," "moderate," or "close," depending on how many gills fit within a given area. This feature is often best observed by looking at the mushroom from the side or using a magnifying glass for precision.

Attachment to the stem is the third key aspect of gills. Gills can attach to the stem in various ways, including being free (not attached), adnate (broadly attached), adnexed (narrowly attached), decurrent (extending down the stem), or notched. For example, the gills of the *Pleurotus* genus (oyster mushrooms) are decurrent, running down the stem, while those of the *Coprinus* genus are free. The attachment style can significantly influence the overall shape and appearance of the mushroom, making it a vital feature for identification.

In summary, when examining the gills of wild mushrooms, focus on their color, spacing, and attachment to the stem. These features, combined with other characteristics like cap shape and spore color, can help narrow down the mushroom's identity. However, it is crucial to approach mushroom foraging with caution, as some species are toxic or deadly. Always consult reliable field guides or experts when in doubt, and avoid consuming wild mushrooms unless you are absolutely certain of their safety.

Cultivating Magic Mushroom Spores: A Step-by-Step Growing Guide

You may want to see also

Stems: size, thickness, and presence of rings or bulbs at the base

When examining the stems of wild mushrooms, size is a critical characteristic to note. Stems can vary widely, typically ranging from 1 to 10 centimeters in height, though some species may grow taller or shorter. For instance, the stems of *Coprinus comatus* (shaggy mane) are often tall and slender, reaching up to 20 centimeters, while those of *Amanita muscaria* (fly agaric) are generally shorter, around 5 to 20 centimeters. Observing the height of the stem relative to the cap provides valuable clues about the mushroom’s identity.

Thickness is another important feature of mushroom stems. Wild mushroom stems can range from delicate and thread-like, measuring just a few millimeters in diameter, to robust and sturdy, exceeding 2 centimeters. For example, the stems of *Marasmius oreades* (fairy ring mushroom) are thin and wiry, while those of *Boletus edulis* (porcini) are thick and stocky. The thickness often correlates with the mushroom’s overall structure and habitat, as thicker stems typically support larger caps or grow in more challenging environments.

The presence of rings or bulbs at the base of the stem is a distinctive trait that aids in identification. A ring, or annulus, is a remnant of the partial veil that once covered the gills and is often found midway up the stem, as seen in *Agaricus* species (such as the common button mushroom). In contrast, a bulb at the base of the stem is a swollen, often rounded structure, characteristic of many *Amanita* species. For instance, *Amanita phalloides* (death cap) has a prominent bulbous base, which is a key warning sign of its toxicity.

Rings and bulbs serve as protective structures during the mushroom’s development but also act as diagnostic features for foragers and mycologists. The absence of these features is equally important, as it narrows down the possible species. For example, *Cantharellus cibarius* (golden chanterelle) lacks both a ring and a bulb, having a smooth, tapered stem that blends seamlessly into the ground.

When assessing stems, it’s essential to consider these features in combination with other characteristics, such as color, texture, and attachment to the cap. For instance, a stem with a ring and a bulbous base is highly suggestive of an *Amanita*, but further examination of the cap, gills, and habitat is necessary for precise identification. Always handle wild mushrooms with care, especially when noting stem features, as some species are toxic or fragile.

Can Mushrooms Grow from Semen? Unraveling the Myth and Science

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Colors: ranging from white and brown to vibrant reds, blues, and greens

Wild mushrooms exhibit a stunning array of colors, making them a fascinating subject for foragers and nature enthusiasts alike. At the more subdued end of the spectrum, white and brown mushrooms are among the most common. These colors often signify species like the ubiquitous button mushroom or the more elusive chanterelles, which range from pale cream to deep brown. White mushrooms, such as the delicate fairy-ring mushroom, often blend seamlessly with their surroundings, while brown varieties, like the turkey tail fungus, display intricate patterns and textures that mimic the forest floor. These earthy tones provide excellent camouflage, helping the mushrooms thrive in their natural habitats.

Moving beyond the neutral palette, vibrant reds are a striking feature of certain wild mushrooms. The scarlet elf cup, for instance, boasts a bright red interior that contrasts sharply with its darker exterior, making it a standout in damp, woody areas. Similarly, the red-banded polypore displays bold red bands on its cap, adding a splash of color to decaying trees. These red hues often serve as a warning to potential predators, as many red mushrooms are toxic or unpalatable. Foragers must exercise caution when encountering these eye-catching species.

Blues and greens are less common but equally captivating in the mushroom world. The indigo milk cap, with its vivid blue cap, is a prime example of nature's artistry. When damaged, it exudes a blue latex, further enhancing its unique appearance. Green mushrooms, such as the verdigris agaric, often owe their color to algae or environmental factors. These hues are particularly striking in shaded, moist environments, where they seem to glow against the dark backdrop. Both blue and green mushrooms are relatively rare, making their discovery a special treat for mushroom enthusiasts.

The diversity in mushroom colors is not merely aesthetic; it often serves functional purposes, such as attracting spore-dispersing insects or deterring predators. For example, yellow and orange mushrooms, like the sulfur tuft or the chicken of the woods, use their bright colors to stand out in their surroundings, aiding in spore dispersal. These warmer tones are particularly common in species that grow on wood or in open areas where visibility is key. Understanding these color variations can also help foragers distinguish between edible and toxic species, as certain colors are often associated with specific chemical compositions.

Finally, multicolored or patterned mushrooms add another layer of complexity to the fungal color palette. Species like the lattice stinkhorn or the amethyst deceiver showcase intricate patterns and gradients, combining hues of purple, brown, and white. These mushrooms often rely on their unique appearances to attract flies or other insects for spore dispersal. Observing these colorful and patterned species in the wild highlights the incredible diversity and adaptability of mushrooms, making them a rewarding subject for exploration and study.

Mastering Mushroom Sclerotia Growth: Essential Tips for Successful Cultivation

You may want to see also

Textures: smooth, scaly, slimy, or fibrous surfaces on caps and stems

Wild mushrooms exhibit a diverse range of textures on their caps and stems, which can be broadly categorized into smooth, scaly, slimy, or fibrous surfaces. Each texture provides clues about the mushroom's species, habitat, and maturity. Smooth textures are common in many wild mushrooms, where the cap and stem feel even and uninterrupted to the touch. For example, the *Agaricus* genus, which includes the familiar button mushroom, often has a smooth cap, especially when young. This texture is typically accompanied by a matte or slightly shiny appearance, depending on moisture levels in the environment. Smooth surfaces are often indicative of mushrooms that grow in open, well-drained areas, as they are less likely to retain debris or develop surface irregularities.

In contrast, scaly textures are characterized by small, raised bumps or flakes on the cap or stem. The *Boletus* genus, such as the prized porcini (*Boletus edulis*), often features a scaly cap, with the scales becoming more pronounced as the mushroom matures. These scales can range from fine and subtle to coarse and prominent, sometimes resembling the texture of reptile skin. Scaly surfaces are often associated with mushrooms that grow in forested areas, where the scales may help shed water or deter insects. Observing the pattern and size of the scales can aid in identification, as these traits are often species-specific.

Slime-coated mushrooms present a distinct texture, where the cap and sometimes the stem are covered in a gelatinous or sticky layer. The *Exidia* genus, often referred to as "black witch’s butter," is a prime example, with its slimy, glossy appearance. This texture is typically an adaptation to retain moisture in drier environments or to discourage predators. Slimy surfaces can be challenging to handle but are easily recognizable due to their unusual tactile quality. It’s important to note that while some slimy mushrooms are edible, many are not, so caution is advised.

Fibrous textures are another common feature, where the cap or stem has a visibly thread-like or stringy surface. The *Pholiota* genus, for instance, often has a fibrous cap with a felt-like or matted appearance. Similarly, the stems of many mushrooms, such as the *Coprinus* genus, may have a fibrous or hairy texture, which can aid in anchoring the mushroom to its substrate. Fibrous surfaces are often found in mushrooms that grow on wood or in decaying organic matter, where the texture may help with nutrient absorption or structural support. Examining the direction and density of the fibers can provide additional insights into the mushroom's identity.

Understanding these textures—smooth, scaly, slimy, or fibrous—is crucial for accurately identifying wild mushrooms. Each texture not only contributes to the mushroom's visual and tactile characteristics but also reflects its ecological role and evolutionary adaptations. Foraging enthusiasts should pay close attention to these details, as they can distinguish between edible and toxic species. Always remember that texture should be considered alongside other features like color, shape, and habitat for a comprehensive identification.

Growing Mushrooms in Northwest Montana: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Wild mushrooms come in a variety of colors, including white, brown, red, yellow, orange, green, purple, and even blue. The color can vary depending on the species and environmental factors.

No, not all wild mushrooms have a typical cap-and-stem structure. Some, like coral mushrooms, grow in branching formations, while others, like puffballs, are spherical and lack a distinct stem.

Wild mushrooms can have caps that are convex, flat, bell-shaped, or even umbrella-like. Stems can be thick, thin, smooth, or scaly. Some mushrooms also have gills, pores, or spines under the cap.

No, wild mushrooms often grow in clusters, rings, or groups, depending on the species. Some, like fairy ring mushrooms, form circular patterns in the ground.

Wild mushrooms vary widely in size. Some are tiny, less than an inch tall, while others, like the giant puffball, can grow up to a foot in diameter. Most common species range from 1 to 6 inches in height.