Dead morel mushrooms, unlike their vibrant, honeycomb-capped living counterparts, undergo noticeable changes in appearance. As they decay, their distinctive ridged and pitted caps lose their firm texture, becoming soft, spongy, and often collapsing inward. The color shifts from the typical shades of tan, brown, or gray to a darker, duller hue, sometimes even appearing slightly slimy or discolored due to mold or bacterial growth. The stem, once sturdy, may become mushy or hollow, and the entire mushroom may emit a foul odor, signaling decomposition. Dead morels are no longer safe to eat and should be avoided, as they can cause illness.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Color | Fades to grayish-brown or black |

| Texture | Becomes soft, mushy, and collapses |

| Shape | Loses its honeycomb-like structure; cap may flatten or disintegrate |

| Odor | Develops a strong, unpleasant, or rancid smell |

| Spores | May release spores, appearing dusty or powdery |

| Surface | Pitched or ridged surface becomes smooth or slimy |

| Firmness | Turns spongy or squishy to the touch |

| Presence of Bugs | Attracts insects or larvae |

| Edibility | Unsafe to eat; toxic compounds may develop |

| Size | Shrinks or becomes deformed |

| Moisture | Often appears wet or slimy due to decay |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Color Changes: Dead morels turn brown or gray, losing their vibrant yellow, brown, or black hues

- Texture Alterations: They become soft, mushy, or brittle, unlike their firm, spongy living state

- Odor Differences: Dead morels emit a foul, decayed smell, contrasting their mild, earthy aroma when fresh

- Structural Collapse: Caps and stems may collapse or disintegrate, losing their distinctive honeycomb structure

- Mold Presence: White, green, or black mold often grows on dead morels, making them unsafe to eat

Color Changes: Dead morels turn brown or gray, losing their vibrant yellow, brown, or black hues

Dead morels undergo a striking transformation in color as they decay, shifting from their once-vibrant palette to muted tones of brown or gray. This change is a clear indicator of their deterioration, making it essential for foragers to recognize these hues as a warning sign. Fresh morels typically boast shades of yellow, brown, or black, depending on the species, but as they age, these colors fade, leaving behind a dull, lifeless appearance. Understanding this color shift is crucial for anyone seeking to identify edible morels in the wild, as consuming a dead or decaying mushroom can lead to unpleasant digestive issues.

The process of color change in dead morels is not merely aesthetic; it reflects the breakdown of cellular structures within the mushroom. As the morel loses its structural integrity, pigments that once contributed to its vivid appearance begin to degrade. For instance, the yellow hues in *Morchella esculenta* or the dark tones in *Morchella elata* dissipate, replaced by the uniform brown or gray of decay. This transformation occurs rapidly, often within a few days of the mushroom’s prime, making timely harvesting critical. Foragers should inspect the mushroom’s color closely, noting any uniformity or dullness that suggests it is past its edible stage.

To avoid confusion, compare the mushroom in question to known images of fresh and dead morels. Fresh morels have distinct ridges and pits with sharp, contrasting colors, while dead ones appear flattened and monochromatic. A practical tip is to gently press the mushroom’s cap; if it feels soft or mushy, it’s likely decaying. Additionally, dead morels often emit a sour or off-putting odor, further confirming their unsuitability for consumption. By focusing on these color and texture changes, foragers can ensure they only collect mushrooms at their peak.

For those new to morel hunting, a simple rule of thumb is to avoid any mushroom that lacks the vibrant, earthy tones characteristic of fresh specimens. Instead, look for the rich yellows, browns, or blacks that signify a healthy, edible morel. If you encounter a mushroom with a gray or brown hue, leave it behind and continue your search. Remember, the goal is not just to find morels but to find *edible* morels, and color is one of the most reliable indicators of their condition. By mastering this aspect of identification, you’ll enhance both your foraging success and safety.

Indian Pipe: Mushroom or Not?

You may want to see also

Texture Alterations: They become soft, mushy, or brittle, unlike their firm, spongy living state

A morel mushroom's texture is one of its most distinctive features when fresh, characterized by a firm, spongy structure that feels almost honeycomb-like to the touch. This unique texture is not just a sensory delight but also a crucial indicator of the mushroom's vitality. However, as morels age or die, their texture undergoes dramatic changes, transforming from a resilient, springy form to something far less appealing. Understanding these texture alterations is essential for foragers and culinary enthusiasts alike, as it directly impacts both safety and quality.

The first noticeable change in a dead morel is its loss of firmness. Instead of the robust, almost bouncy texture of a living morel, a dead one becomes soft and mushy. This occurs as the mushroom's cellular structure breaks down, releasing moisture and causing the once-rigid walls of its sponge-like interior to collapse. Foraging tip: if a morel compresses easily under gentle pressure, it’s likely past its prime. Avoid harvesting such specimens, as their degraded texture also indicates a higher risk of spoilage or contamination.

In contrast to the softness, some dead morels exhibit brittleness, particularly in drier conditions. As the mushroom loses moisture, its structure becomes fragile, and the once-pliable ridges and pits turn dry and crack-prone. This brittle state is not just unappealing for cooking—it also signals a loss of the mushroom's natural defenses, making it more susceptible to mold or insect infestation. Practical advice: store fresh morels in a breathable container (like a paper bag) in the refrigerator to maintain their optimal texture for 2–3 days. Avoid plastic bags, as they trap moisture and accelerate decay.

For culinary purposes, texture alterations in morels can ruin a dish. A soft, mushy morel will disintegrate during cooking, losing its shape and mouthfeel, while a brittle one may become unpleasantly chewy or powdery. To salvage marginally affected morels, consider drying them for long-term storage. Drying not only preserves their flavor but also transforms their texture into a lightweight, crisp form ideal for rehydration in soups, stews, or sauces. Step-by-step: clean the morels, slice them if large, and dehydrate at 125°F (52°C) for 6–8 hours until completely dry. Store in an airtight container in a cool, dark place for up to a year.

In summary, the texture of a dead morel mushroom is a telltale sign of its condition, shifting from firm and spongy to either soft and mushy or dry and brittle. These changes not only affect its culinary utility but also serve as a warning for potential safety issues. By recognizing these alterations and adapting storage or preparation methods accordingly, foragers and cooks can ensure they make the most of this prized fungus while avoiding waste or risk.

Mushrooms: Nature's Anti-Inflammatory Superfood?

You may want to see also

Odor Differences: Dead morels emit a foul, decayed smell, contrasting their mild, earthy aroma when fresh

A morel's scent is its silent alarm, shifting dramatically from life to death. Fresh morels whisper a mild, earthy aroma, akin to damp forest floor or fresh rain on soil. This subtle fragrance is a forager’s cue, signaling edibility and prime condition. But decay transforms this delicate scent into a pungent warning. Dead morels emit a foul, decayed smell, reminiscent of rotting vegetables or spoiled meat. This olfactory shift is not merely unpleasant—it’s a biological red flag, indicating the breakdown of cellular structures and the proliferation of harmful bacteria.

Foraging requires more than sight; it demands attention to smell. To assess a morel’s freshness, gently crush a small portion between your fingers and inhale. A fresh specimen will release a clean, woodland scent, while a dead one will assault your senses with a putrid odor. This simple test is critical, as consuming morels past their prime can lead to gastrointestinal distress. Always trust your nose over your eyes—even morels that appear structurally intact may be spoiled.

The contrast in aroma is rooted in chemistry. Fresh morels contain volatile organic compounds (VOCs) like aldehydes and ketones, which contribute to their earthy fragrance. As they decompose, enzymes break down proteins and lipids, releasing sulfur compounds and amines responsible for the foul smell. This process accelerates in warm, moist environments, so foragers in humid climates should be particularly vigilant. Storing morels in a cool, dry place can slow decay, but once the odor turns, there’s no reversing the damage.

Practical tip: If you’re unsure about a morel’s freshness, err on the side of caution. Even slightly off-smelling specimens should be discarded. Foraging guides often emphasize visual cues, but odor is equally—if not more—critical. Carry a small container with a tight lid to isolate questionable finds and prevent their smell from contaminating your harvest. Remember, a morel’s scent is its final word on edibility—ignore it at your peril.

In the end, the odor difference between fresh and dead morels is a lesson in nature’s precision. It’s a reminder that foraging is not just about finding food but about understanding the delicate balance of life and decay. By mastering this olfactory distinction, you’ll not only safeguard your health but also deepen your connection to the forest’s rhythms. Let your nose be your guide, and the morels will reveal their secrets—one scent at a time.

Mushroom Cultivation: A Beginner's Guide to Success

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Structural Collapse: Caps and stems may collapse or disintegrate, losing their distinctive honeycomb structure

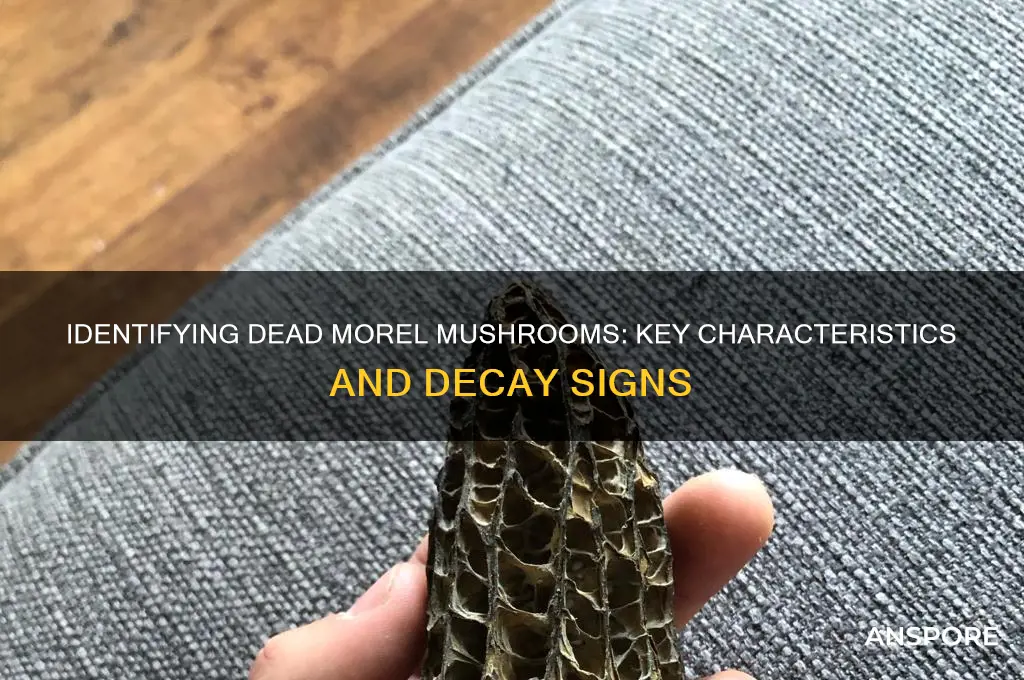

A morel mushroom's allure lies in its intricate, honeycomb-like cap and sturdy stem. But when death claims this fungi, structural collapse becomes its defining feature. The once-rigid cap, a marvel of nature's architecture, begins to sag and crumble, its delicate ridges dissolving into a sad, formless mass. The stem, too, loses its battle against decay, becoming brittle and prone to snapping under the slightest pressure.

This disintegration is a stark reminder of the morel's ephemeral nature, a fleeting beauty that demands timely harvesting.

Imagine a once-grand cathedral, its arches and columns now reduced to rubble. This is the fate of a dead morel. The honeycomb structure, a hallmark of its identity, vanishes, leaving behind a mere shadow of its former self. This collapse isn't merely aesthetic; it signifies a breakdown in the mushroom's cellular structure, rendering it unsuitable for consumption. The very qualities that make morels prized – their texture and flavor – are irrevocably lost in this process.

Foraging enthusiasts must be vigilant, as a morel past its prime can be easily mistaken for its younger, edible counterpart.

The collapse isn't instantaneous. It's a gradual process, a slow surrender to the elements. Initially, the cap may appear slightly softer, its ridges less defined. The stem might feel hollow, lacking the firmness of a fresh morel. As decomposition progresses, the mushroom becomes increasingly fragile, its structure unable to withstand even gentle handling. This vulnerability underscores the importance of careful inspection when foraging. A morel with a compromised structure should be left behind, as its consumption can lead to gastrointestinal discomfort.

Foraging guides often advise against harvesting morels with caps that easily detach from the stem, a clear sign of impending collapse.

Understanding this structural collapse is crucial for both culinary enthusiasts and nature observers. It serves as a reminder of the delicate balance between life and decay, a cycle that governs all living things, even the enigmatic morel mushroom. By recognizing the signs of structural deterioration, we not only ensure a safe and enjoyable culinary experience but also deepen our appreciation for the fleeting beauty of these forest treasures.

Brewing Chaga Mushrooms: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Mold Presence: White, green, or black mold often grows on dead morels, making them unsafe to eat

Dead morels, once prized for their earthy flavor and unique honeycomb texture, can quickly become a hazard when mold takes hold. White, green, or black mold colonies often flourish on these decomposing fungi, rendering them unsafe for consumption. This mold growth is a clear indicator that the morel has passed its prime and should be avoided. The presence of mold not only spoils the mushroom’s texture and taste but also introduces potential health risks, including allergic reactions or toxic effects from mycotoxins.

To identify mold on dead morels, look for fuzzy or powdery patches that contrast with the mushroom’s natural ridges. White mold may appear as a fine, cotton-like layer, while green mold often resembles a slimy, moss-like growth. Black mold, the most alarming, presents as dark, irregular spots or streaks. These colors are not merely aesthetic changes; they signal active fungal decomposition. If you spot any of these signs, discard the morel immediately—no amount of cleaning or cooking can eliminate the toxins produced by mold.

Preventing mold growth begins with proper harvesting and storage. Fresh morels should be cleaned gently with a brush to remove dirt and debris, then stored in breathable containers like paper bags or loosely woven baskets. Avoid airtight plastic bags, as they trap moisture and accelerate decay. For longer preservation, consider drying or freezing morels within 24 hours of harvesting. Drying involves laying them flat in a well-ventilated area or using a dehydrator at 125°F (52°C) until brittle. Frozen morels should be blanched for 2–3 minutes before being sealed in airtight bags.

If you’re foraging, inspect morels closely before collecting. Dead or decaying specimens often feel soft, spongy, or discolored, even before mold appears. Trust your senses: a healthy morel should have a firm yet pliable texture and a fresh, earthy aroma. When in doubt, leave it behind—the risk of consuming moldy mushrooms far outweighs the reward. Remember, mold is nature’s cleanup crew, breaking down organic matter, but it’s not an ingredient you want in your meal.

Finally, educate yourself on the visual cues of mold growth to protect your health and culinary experience. While morels are a forager’s treasure, their delicate nature demands respect and vigilance. By recognizing the signs of mold and adopting proper handling practices, you can safely enjoy these mushrooms while avoiding the pitfalls of decay. Always prioritize caution over curiosity when it comes to wild-harvested foods.

Brain-Like Mushroom: Hallucinogenic or Harmless Look-Alike?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A dead morel mushroom typically turns dark brown or black as it decomposes, losing its characteristic light brown or tan color.

No, a dead morel mushroom often becomes soft, mushy, and loses its distinct honeycomb-like ridges as it breaks down.

A dead morel will still have a hollow stem and lack the wrinkled, brain-like cap of a false morel, though its texture and color will be significantly deteriorated.