Mushroom gills, located on the underside of the cap in many species, play a crucial role in the reproductive process of fungi. These thin, blade-like structures serve as the primary site for spore production and dispersal. As the mushroom matures, the gills release countless microscopic spores into the surrounding environment, which are then carried away by air currents or other means to colonize new areas. Beyond reproduction, gills also contribute to the mushroom's overall structure and stability, providing a large surface area for gas exchange, which is essential for the fungus's metabolic processes. Understanding the function of mushroom gills not only sheds light on fungal biology but also highlights their importance in ecosystems as decomposers and nutrient recyclers.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Function | Spores are produced on the gills and dispersed into the environment, aiding in mushroom reproduction. |

| Structure | Thin, papery, or fleshy sheets radiating from the mushroom's stem, attached to the cap (pileus). |

| Types | Varied shapes (e.g., sinuate, adnate, free) and spacing, depending on mushroom species. |

| Color | Ranges from white, cream, pink, brown, to black, often changing with age or spore maturity. |

| Spore Production | Spores are formed on the gill surface (hymenium) and released when mature. |

| Taxonomic Importance | Gill structure and attachment are key identifiers for classifying mushroom species. |

| Environmental Role | Facilitates spore dispersal, contributing to fungal ecosystem dynamics and decomposition processes. |

| Edibility Indicator | Gill color and structure can help distinguish edible from poisonous mushrooms. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Production: Gills produce and release spores for mushroom reproduction and species propagation

- Surface Area: Gills maximize surface area for efficient spore dispersal and growth

- Classification: Gill structure helps identify mushroom species based on shape, color, and attachment

- Nutrient Exchange: Gills aid in nutrient absorption and gas exchange for mushroom metabolism

- Protection: Gills shield spores from predators and environmental damage during development

Spore Production: Gills produce and release spores for mushroom reproduction and species propagation

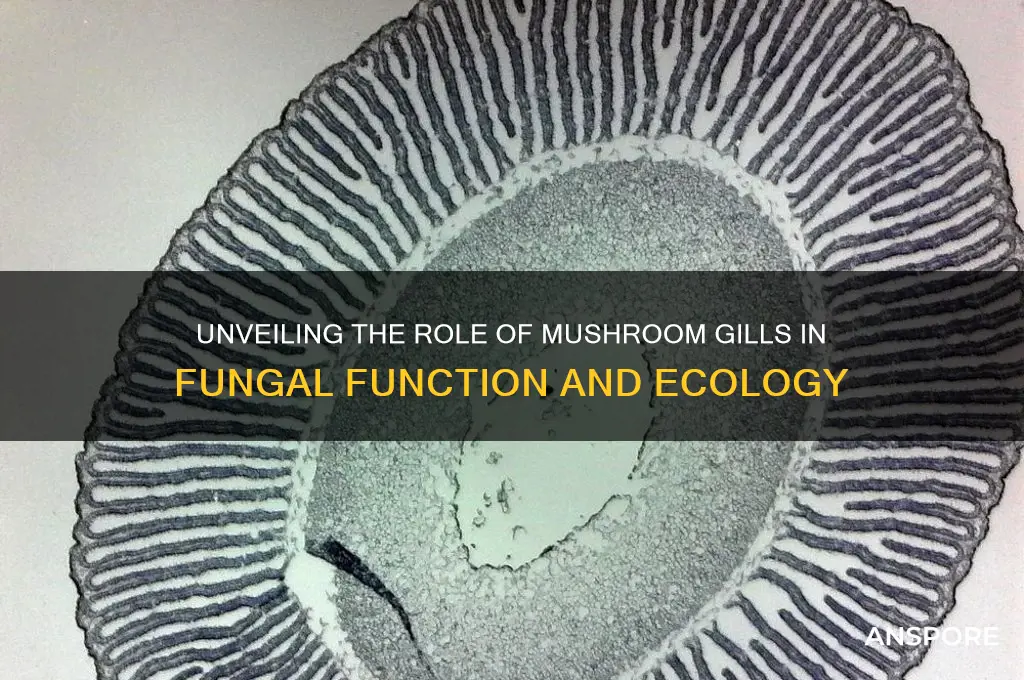

Mushroom gills are essential structures for spore production, playing a critical role in the reproductive cycle of fungi. Located on the underside of the mushroom cap, gills are thin, blade-like structures that maximize surface area, which is crucial for efficient spore dispersal. Each gill is lined with basidia, microscopic, club-shaped cells that produce and bear spores. This anatomical design ensures that mushrooms can generate and release vast quantities of spores, facilitating reproduction and species propagation. Without gills, many mushroom species would lack an effective mechanism for dispersing their genetic material into the environment.

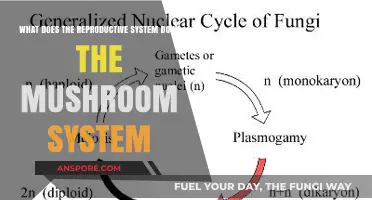

The process of spore production begins within the basidia on the gills. Through a specialized form of cell division called meiosis, each basidium typically produces four spores. These spores are haploid, meaning they contain half the genetic material of the parent mushroom. Once mature, the spores are released from the basidia and become airborne or are carried away by water, animals, or other environmental factors. This dispersal mechanism allows mushrooms to colonize new habitats and ensures the survival and spread of the species. The gill’s structure, with its extensive surface area, enables a single mushroom to produce millions of spores, increasing the likelihood of successful reproduction.

Gills are specifically adapted to optimize spore release. Their thin, papery texture and spacing allow air currents to pass through, carrying spores away from the mushroom. In some species, the gills even dry out as the mushroom matures, further aiding in spore dispersal. This adaptation is particularly important for fungi, which cannot move to find mates or new habitats. Instead, they rely on the wind, water, or animals to transport their spores to suitable environments where they can germinate and grow into new individuals.

The efficiency of gill-based spore production is a key factor in the success of mushrooms as a group. By producing and releasing spores in such large numbers, mushrooms increase their chances of finding favorable conditions for growth. Spores can remain dormant for extended periods, waiting for the right combination of moisture, temperature, and nutrients to sprout. Once germinated, they develop into thread-like structures called hyphae, which eventually form the mycelium—the vegetative part of the fungus. Over time, under the right conditions, the mycelium produces new mushrooms, completing the life cycle.

In summary, gills are indispensable for spore production, the primary means of mushroom reproduction and species propagation. Their structure and function are finely tuned to produce, bear, and release spores efficiently. By maximizing surface area and facilitating dispersal, gills ensure that mushrooms can spread their genetic material far and wide. This reproductive strategy has allowed fungi to thrive in diverse ecosystems worldwide, highlighting the importance of gills in the fungal life cycle. Understanding gill function provides valuable insights into the biology and ecology of mushrooms, underscoring their role as key players in nutrient cycling and ecosystem health.

Discover the Magic of Porcini Mushroom Powder

You may want to see also

Surface Area: Gills maximize surface area for efficient spore dispersal and growth

Mushroom gills are a critical adaptation that significantly enhances the surface area available for spore production and dispersal. This increased surface area is essential for the mushroom's reproductive strategy, as it allows for the efficient release of a large number of spores into the environment. Gills are typically thin, closely spaced, and radially arranged on the underside of the mushroom cap, forming a structure that maximizes exposure to air currents. This design ensures that spores can be easily dislodged and carried away, increasing the likelihood of successful colonization in new locations.

The maximization of surface area through gills directly supports efficient spore dispersal. Each gill edge, or lamella, is lined with basidia—the spore-bearing cells. By increasing the number of gills and their surface area, mushrooms can produce and release a vastly greater quantity of spores compared to a smooth or less structured surface. This is particularly important in fungi, which rely on wind and other environmental factors for spore dissemination. The intricate network of gills creates numerous microenvironments where spores can accumulate and be released in response to even slight air movements, ensuring widespread distribution.

In addition to spore dispersal, the increased surface area provided by gills promotes optimal conditions for spore development and growth. The thin, exposed nature of gills allows for better gas exchange, which is crucial for the metabolic processes involved in spore maturation. Adequate airflow also helps prevent the accumulation of moisture, reducing the risk of mold or bacterial growth that could hinder spore production. This efficient design ensures that mushrooms can fulfill their reproductive role effectively, even in environments with limited resources or suboptimal conditions.

The structural efficiency of gills is further exemplified by their ability to balance spore retention and release. While maximizing surface area for spore production, gills also provide a platform for temporary spore storage. Spores are initially held in place by a thin film of moisture and the slight adhesiveness of their surfaces, allowing them to accumulate until conditions are favorable for dispersal. Once released, the expansive surface area of the gills ensures that spores are projected outward in all directions, maximizing the potential for colonization.

From an evolutionary perspective, the development of gills as a surface area-maximizing structure has been a key factor in the success of agaricomycetes, the group of fungi that includes most gilled mushrooms. This adaptation has allowed them to dominate diverse ecosystems, from forest floors to decaying wood, by ensuring efficient and widespread spore dispersal. The gill structure’s effectiveness in enhancing surface area highlights its role as a specialized organ evolved specifically for reproductive success, making it a fascinating example of biological optimization in the fungal kingdom.

Chanterelle Mushrooms: A Fungi Friend or Foe?

You may want to see also

Classification: Gill structure helps identify mushroom species based on shape, color, and attachment

The gill structure of mushrooms is a critical feature for mycologists and enthusiasts alike when it comes to identifying different species. Shape is one of the primary characteristics examined. Gills can be broadly classified into several types, such as adnate (broadly attached to the stem), sinuate (wavy and attached along a curve), or free (unattached to the stem). For instance, the gills of the *Agaricus* genus are typically free, while those of the *Pleurotus* genus are decurrent, meaning they extend down the stem. Observing the gill shape provides a foundational clue in narrowing down the mushroom’s identity.

Color is another essential aspect of gill structure in mushroom classification. Gill color can vary dramatically, from pale pink in young *Russula* species to deep purple-black in *Coprinus comatus*. Color changes with age or exposure to air can also be diagnostic. For example, the gills of the *Boletus* genus often start as pale yellow and darken to olive-green or brown as the mushroom matures. Documenting gill color at different stages of development is crucial for accurate identification.

Attachment to the stem is a third key feature in gill-based classification. Gills can be attached in various ways, such as adnexed (narrowly attached), notched (with a small notch at the stem), or decurrent (extending down the stem). The attachment style, combined with shape and color, helps differentiate between closely related species. For instance, the gills of *Lactarius* species are typically decurrent, while those of *Cantharellus* are folded and not true gills but "veins," which is a distinguishing feature.

The interplay of shape, color, and attachment in gill structure allows for precise classification. For example, the *Amanita* genus often has white, free gills, while *Cortinarius* species frequently have rusty-brown, adnate gills. These specific combinations of traits are often unique to particular genera or species, making gill examination a cornerstone of mushroom identification. Field guides and identification keys heavily rely on these characteristics to guide users toward the correct species.

In addition to these primary features, the spacing and thickness of gills also play a role in classification. Some mushrooms have closely packed gills, like those in the *Hypsizygus* genus, while others have widely spaced gills, such as *Stropharia*. Gill thickness can range from paper-thin in *Marasmius* species to robust and fleshy in *Portobello* mushrooms. These additional details, combined with shape, color, and attachment, create a comprehensive profile for accurate species identification.

Understanding gill structure is not only a practical skill for mushroom identification but also a window into the ecological role of fungi. Gills are the primary site of spore production, and their structure often reflects adaptations to specific environments or dispersal methods. By carefully examining gill shape, color, attachment, and other features, one can unlock the intricate world of mushroom diversity and contribute to the broader understanding of fungal taxonomy.

Mushroom Stems vs. Caps: Unveiling Their Nutritional Differences

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$26.95

Nutrient Exchange: Gills aid in nutrient absorption and gas exchange for mushroom metabolism

Mushroom gills are essential structures that play a critical role in the nutrient exchange processes vital for the mushroom's survival and growth. These thin, papery structures are highly specialized for maximizing surface area, which is crucial for efficient absorption of nutrients and gases from the surrounding environment. Gills are typically located on the underside of the mushroom cap and are arranged in a radial pattern, allowing for optimal exposure to the substrate and air. This strategic placement ensures that the mushroom can effectively interact with its environment, facilitating the metabolic processes necessary for its development.

The primary function of mushroom gills in nutrient exchange is to absorb water and dissolved minerals from the substrate. As mushrooms lack a vascular system, they rely on passive absorption through their extensive surface area. The gills are composed of densely packed hyphae, the thread-like structures of the fungus, which are permeable to water and nutrients. When the gills come into contact with a moist substrate, water and minerals are drawn into the hyphae through osmosis and diffusion. This process is essential for the mushroom's growth, as it provides the necessary resources for cellular functions, including energy production and structural development.

In addition to nutrient absorption, gills are instrumental in gas exchange, a fundamental aspect of mushroom metabolism. Like all living organisms, mushrooms require oxygen for cellular respiration and produce carbon dioxide as a byproduct. The large surface area of the gills facilitates the diffusion of oxygen into the mushroom's tissues and the release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. This efficient gas exchange is crucial for maintaining the mushroom's metabolic rate and ensuring that its cells receive the oxygen needed for energy production. Without this mechanism, the mushroom's growth and reproductive capabilities would be severely compromised.

The structure of the gills is finely tuned to optimize both nutrient absorption and gas exchange. Their thin, blade-like design minimizes the distance between the external environment and the internal hyphae, reducing the diffusion pathway for gases and nutrients. Furthermore, the spacing between individual gills allows for adequate air circulation, preventing the buildup of carbon dioxide and ensuring a continuous supply of oxygen. This architectural efficiency highlights the evolutionary adaptation of mushrooms to thrive in diverse environments, from forest floors to decaying wood.

Understanding the role of gills in nutrient exchange also sheds light on the ecological significance of mushrooms. As decomposers, mushrooms break down organic matter, recycling nutrients back into the ecosystem. The gills' ability to efficiently absorb and process nutrients enables mushrooms to contribute to nutrient cycling, supporting the health of their habitats. Additionally, the metabolic processes facilitated by gills, including gas exchange, underscore the interconnectedness of fungal life with the broader environment, emphasizing their role as key players in ecosystem dynamics.

In summary, mushroom gills are indispensable for nutrient exchange, serving as the primary interface for nutrient absorption and gas exchange. Their specialized structure maximizes surface area, enabling efficient osmosis, diffusion, and respiration. This functionality not only supports the mushroom's metabolic needs but also highlights its ecological role in nutrient cycling and environmental balance. By examining the gills' role in nutrient exchange, we gain a deeper appreciation for the complexity and importance of these often-overlooked organisms in the natural world.

Mushroom Legality: Exploring the Fungal Grey Area

You may want to see also

Protection: Gills shield spores from predators and environmental damage during development

Mushroom gills play a crucial role in protecting developing spores from predators and environmental damage. Positioned beneath the cap, gills are thin, closely spaced structures that provide a physical barrier against potential threats. This arrangement shields the spores from direct exposure to insects, small invertebrates, and other organisms that might consume them. By housing the spores within the intricate network of gills, mushrooms create a microenvironment that is less accessible to predators, thereby increasing the chances of spore survival and successful dispersal.

In addition to predator protection, gills offer a defense mechanism against environmental stressors such as desiccation, UV radiation, and mechanical damage. The dense arrangement of gills helps retain moisture around the spores, preventing them from drying out in arid conditions. This moisture retention is vital for spore viability, as dehydration can render them non-functional. Furthermore, the gills' structure provides a degree of shading, reducing the impact of harmful UV radiation that could otherwise damage the delicate genetic material within the spores.

The intricate design of gills also minimizes the risk of mechanical damage from wind, rain, or other physical forces. Their flexible yet robust nature allows them to absorb and dissipate energy from external impacts, safeguarding the spores nestled within. This protective function is particularly important during the early stages of spore development, when they are most vulnerable to disruption. By acting as a buffer, gills ensure that spores remain intact and functional until they are ready for dispersal.

Another aspect of gill protection is their role in regulating the microclimate around the spores. The narrow spaces between gills create a stable environment with controlled humidity and temperature levels, which are essential for spore maturation. This microclimate regulation further shields spores from sudden environmental fluctuations that could hinder their development. Thus, gills serve as both a physical and environmental safeguard, optimizing conditions for spore growth and resilience.

Lastly, the protective function of gills extends to their role in preventing premature spore release. By enclosing spores within their structure, gills ensure that they are released only when conditions are favorable for dispersal. This timing is critical, as premature release could expose spores to adverse conditions or predators before they are ready. Through this mechanism, gills act as a strategic defense system, balancing protection with the eventual need for spore dissemination to ensure the mushroom's reproductive success.

Mushroom Magic: PSK Extraction Process in Japan

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mushroom gills serve as the primary site for spore production and dispersal, enabling mushrooms to reproduce.

Mushroom gills contain basidia, specialized cells that produce and release spores through a process called meiosis.

The color of mushroom gills is determined by the type of spores produced and can vary by species, aiding in identification.

Yes, the color, attachment, and structure of mushroom gills are key features used to identify mushroom species, including edible ones.

No, not all mushrooms have gills. Some species have pores, teeth, or other structures instead, depending on their classification.