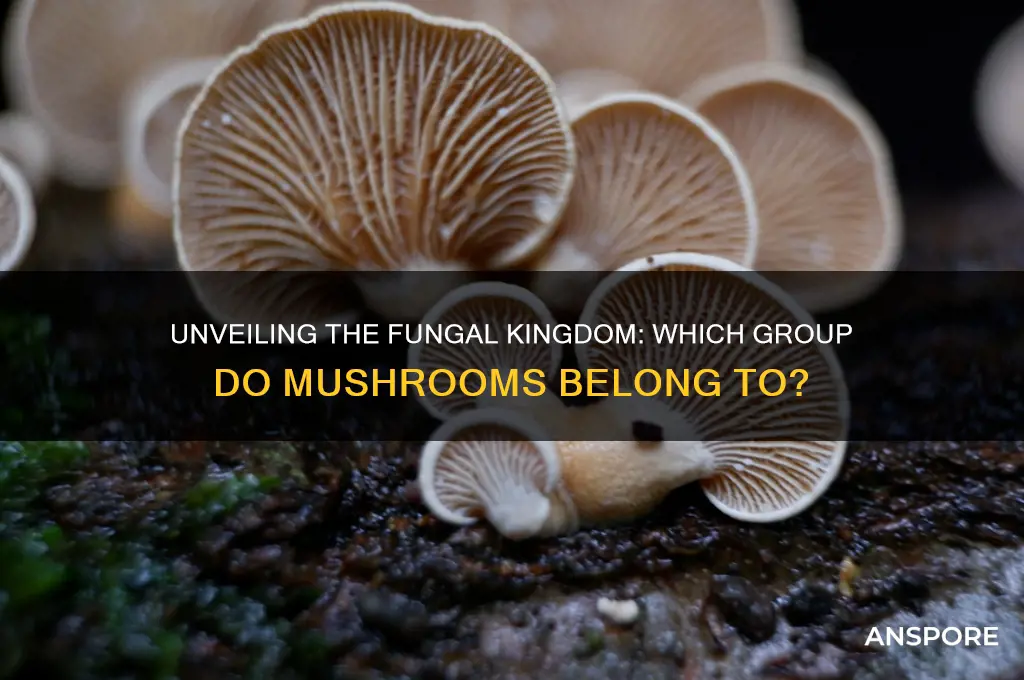

Mushrooms, often recognized for their distinctive caps and stems, belong to the fungal group known as Basidiomycetes, which is one of the largest and most diverse groups within the kingdom Fungi. Basidiomycetes are characterized by the production of basidiospores, which develop on specialized structures called basidia. These fungi play crucial roles in ecosystems, particularly in nutrient cycling and symbiotic relationships with plants. Beyond mushrooms, this group also includes bracket fungi, puffballs, and rusts, highlighting its ecological and biological significance. Understanding the classification of mushrooms within Basidiomycetes provides insight into their evolutionary history and functional roles in nature.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Basidiomycota Classification: Mushrooms primarily belong to the Basidiomycota division, known for basidiospores

- Agaricomycetes Class: Most mushrooms are in the Agaricomycetes class, featuring diverse fruiting bodies

- Basidiocarp Structure: Mushrooms are basidiocarps, the reproductive structures of Basidiomycota fungi

- Gilled vs. Pored: Mushrooms are grouped by gill or pore structures under Agaricomycetes

- Ecology of Mushrooms: Basidiomycota mushrooms play key roles in ecosystems as decomposers and symbionts

Basidiomycota Classification: Mushrooms primarily belong to the Basidiomycota division, known for basidiospores

Mushrooms, a diverse and fascinating group of fungi, are primarily classified within the Basidiomycota division, one of the two largest groups of fungi, the other being Ascomycota. This classification is based on their unique reproductive structures and life cycle. Basidiomycota is distinguished by the production of basidiospores, which are external spores formed on specialized cells called basidia. These spores are crucial for the dispersal and reproduction of mushrooms, making them a defining feature of this fungal group. Understanding this classification is essential for anyone studying mycology, as it provides insights into the evolutionary relationships and ecological roles of mushrooms.

The Basidiomycota division encompasses a wide range of fungi, including not only mushrooms but also puffballs, bracket fungi, rusts, and smuts. However, mushrooms are perhaps the most recognizable members of this group due to their fruiting bodies, which are the visible structures we commonly see above ground. These fruiting bodies are the reproductive organs of the fungus, producing and releasing basidiospores into the environment. The basidia, typically club-shaped structures, bear these spores externally, a characteristic that sets Basidiomycota apart from other fungal groups like Ascomycota, which produce spores internally within asci.

Within the Basidiomycota division, mushrooms are further classified into various orders, such as Agaricales (which includes common button mushrooms and shiitakes), Boletales (porcini and chanterelles), and Russulales (milk-caps and brittlegills). Each order is defined by specific morphological, ecological, and genetic traits. For example, Agaricales are known for their gill-like structures under the cap where basidiospores are produced, while Boletales typically have sponge-like pores instead of gills. This hierarchical classification system helps mycologists organize and study the vast diversity of mushroom species.

The life cycle of Basidiomycota fungi, including mushrooms, involves both haploid and dikaryotic phases, a process known as alternation of generations. After basidiospores germinate, they grow into haploid mycelia, which can then fuse with compatible individuals to form dikaryotic mycelia. This dikaryotic phase eventually produces the fruiting bodies we recognize as mushrooms. The basidia within these fruiting bodies undergo karyogamy (nuclear fusion) and meiosis to form haploid basidiospores, completing the life cycle. This complex reproductive strategy contributes to the genetic diversity and adaptability of mushrooms.

In summary, mushrooms belong to the Basidiomycota division, a classification defined by their production of basidiospores on basidia. This group includes a wide array of fungi, with mushrooms being among the most prominent and ecologically significant members. Their classification into orders like Agaricales and Boletales highlights the diversity within Basidiomycota, while their unique life cycle underscores the evolutionary success of this fungal group. Understanding the Basidiomycota classification is fundamental to appreciating the biology, ecology, and importance of mushrooms in ecosystems worldwide.

Portabella Mushrooms: How Many Make a Serving?

You may want to see also

Agaricomycetes Class: Most mushrooms are in the Agaricomycetes class, featuring diverse fruiting bodies

The Agaricomycetes class is a prominent group within the fungal kingdom, encompassing the majority of what we commonly recognize as mushrooms. This class is characterized by its remarkable diversity in fruiting body structures, which are the visible, above-ground parts of the fungus that produce and disperse spores. These fruiting bodies come in various shapes, sizes, and colors, making Agaricomycetes one of the most visually striking and recognizable fungal groups. From the delicate, lacy forms of coral fungi to the robust, umbrella-shaped caps of agarics, the class showcases an extraordinary range of morphological adaptations.

Agaricomycetes are primarily saprotrophic, meaning they obtain nutrients by decomposing organic matter, particularly wood and plant material. This ecological role is vital in nutrient cycling and ecosystem health, as these fungi break down complex organic compounds, returning essential elements to the soil. The class includes some of the most efficient decomposers in nature, capable of degrading lignin and cellulose, which are major components of plant cell walls and are otherwise difficult to decompose. This ability has led to significant interest in Agaricomycetes for biotechnological applications, such as in biofuel production and paper recycling.

The diversity within Agaricomycetes is not only morphological but also ecological. Species in this class can be found in almost every habitat on Earth, from tropical rainforests to arctic tundra. They form various symbiotic relationships, including mycorrhizal associations with plants, where the fungus enhances the plant's nutrient uptake in exchange for carbohydrates. Some Agaricomycetes are also parasitic, causing diseases in plants and, occasionally, animals. This ecological versatility contributes to the class's success and widespread distribution.

One of the most fascinating aspects of Agaricomycetes is their reproductive strategy. The fruiting bodies are ephemeral structures produced under specific environmental conditions, often after a period of sufficient moisture and temperature. These bodies release spores into the air, which can travel great distances, ensuring the fungus's survival and colonization of new habitats. The study of spore dispersal and the factors triggering fruiting body formation is an active area of research, offering insights into fungal ecology and potential applications in agriculture and conservation.

In summary, the Agaricomycetes class is a diverse and ecologically significant group of fungi, primarily known for its mushroom-forming species. Their ability to decompose complex organic matter, form symbiotic relationships, and produce a wide array of fruiting bodies makes them a subject of great interest in various scientific fields. Understanding Agaricomycetes contributes not only to mycology but also to ecology, biotechnology, and conservation efforts, highlighting their importance in both natural and applied sciences.

Mushrooms: Invasive or Not?

You may want to see also

Basidiocarp Structure: Mushrooms are basidiocarps, the reproductive structures of Basidiomycota fungi

Mushrooms, the familiar fruiting bodies we often see in forests or on supermarket shelves, are technically known as basidiocarps. These structures are the reproductive organs of fungi belonging to the phylum Basidiomycota, one of the most diverse and ecologically significant groups of fungi. Basidiocarps are the visible manifestation of the fungus's life cycle, emerging from a network of thread-like structures called mycelium that grows underground or within decaying organic matter. The primary function of the basidiocarp is to produce and disperse spores, ensuring the continuation of the fungal species.

The structure of a basidiocarp is highly specialized to facilitate spore production and dispersal. A typical mushroom consists of several key parts: the pileus (cap), the stipe (stem), the gills (or pores/teeth in some species), and the veil (a membrane that often covers the gills in young mushrooms). The gills, located on the underside of the cap, are where the spores are produced. In Basidiomycota, spores develop on microscopic, club-shaped structures called basidia, which line the gills. Each basidium typically bears four spores, giving this group its name (from the Greek *basidion*, meaning "little pedestal").

The development of a basidiocarp begins when environmental conditions, such as moisture and temperature, signal the mycelium to allocate resources toward reproductive growth. The mycelium aggregates and forms a primordium, the initial stage of the basidiocarp. As the primordium grows, it differentiates into the cap, stem, and other structures. The gills or pore surfaces expand, providing ample area for basidia to form and spores to mature. Once the spores are fully developed, they are released into the environment, often aided by wind or water, to colonize new habitats.

The diversity of basidiocarp structures reflects the adaptability of Basidiomycota fungi to various ecological niches. For example, some mushrooms have gills (e.g., agarics), while others have pores (e.g., boletes) or spines (e.g., hydnoid fungi). These variations optimize spore dispersal in different environments. Additionally, the size, shape, and color of basidiocarps can vary widely, often serving as key features for identification. Some mushrooms are edible and highly prized, such as the button mushroom (*Agaricus bisporus*), while others are toxic or hallucinogenic, underscoring the importance of accurate identification.

Understanding the structure and function of basidiocarps is crucial for both scientific research and practical applications. Basidiomycota fungi play vital roles in ecosystems as decomposers, mycorrhizal partners, and pathogens. Their basidiocarps are not only essential for their reproductive cycle but also serve as indicators of forest health and biodiversity. Moreover, the study of basidiocarp development has implications for biotechnology, as these structures produce a wide array of bioactive compounds with potential medicinal and industrial uses. In summary, mushrooms, as basidiocarps of Basidiomycota, are marvels of fungal biology, combining structural complexity with ecological and practical significance.

Mushrooms: The World's Future Dominant Species?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Gilled vs. Pored: Mushrooms are grouped by gill or pore structures under Agaricomycetes

Mushrooms, a familiar and diverse group of fungi, belong to the Agaricomycetes, a class within the Basidiomycota division. This classification is primarily based on their reproductive structures, specifically the way they produce and disperse spores. Within the Agaricomycetes, mushrooms are further categorized based on the structure of their spore-bearing surfaces, leading to the distinction between gilled and pored mushrooms. These structures are not just morphological features but are critical for identifying and classifying mushrooms accurately.

Gilled mushrooms, also known as agarics, are perhaps the most recognizable type of mushroom. Their undersides are characterized by thin, blade-like structures called gills, which radiate outward from the stem. These gills are the fruiting body's spore-bearing surface, where basidia (spore-producing cells) are located. When the spores mature, they are released from the gills and dispersed into the environment, often by wind or water. Examples of gilled mushrooms include the common button mushroom (*Agaricus bisporus*) and the iconic fly agaric (*Amanita muscaria*). The arrangement, color, and attachment of the gills to the stem are key features used in identification.

In contrast, pored mushrooms lack gills and instead have a spongy underside composed of tiny, tube-like structures called pores. These pores open at the surface and contain the basidia, which produce and release spores. Pored mushrooms are commonly known as boletes and polypores. Boletes, such as the king bolete (*Boletus edulis*), typically have a fleshy cap and a spongy pore surface, while polypores, like the turkey tail (*Trametes versicolor*), often have a tougher, woody texture and grow in shelf-like formations. The size, shape, and color of the pores, as well as the overall structure of the fruiting body, are essential for distinguishing pored mushrooms.

The distinction between gilled and pored mushrooms is not merely superficial; it reflects deeper evolutionary relationships within the Agaricomycetes. Gilled mushrooms are primarily found in the order Agaricales, which includes many edible and ecologically significant species. Pored mushrooms, on the other hand, are distributed across multiple orders, including Boletales and Polyporales, each with unique ecological roles, such as mycorrhizal associations or wood decomposition. Understanding these structural differences is crucial for both amateur foragers and professional mycologists, as it aids in accurate identification and highlights the incredible diversity within the fungal kingdom.

In summary, the gilled vs. pored classification under Agaricomycetes is a fundamental aspect of mushroom taxonomy, rooted in the distinct spore-bearing structures of these fungi. While gilled mushrooms rely on exposed gills for spore dispersal, pored mushrooms utilize a network of tubes and pores. Both types play vital roles in ecosystems, from nutrient cycling to symbiotic relationships, and their study continues to reveal the complexity and importance of fungi in the natural world. Whether you encounter a gilled agaric or a pored bolete, recognizing these structures provides a deeper appreciation for the fungal group mushrooms belong to.

Shiitake Mushrooms: Gas and Bloating Side Effects

You may want to see also

Ecology of Mushrooms: Basidiomycota mushrooms play key roles in ecosystems as decomposers and symbionts

Mushrooms, which belong to the fungal group Basidiomycota, are ecologically vital organisms that significantly influence ecosystem dynamics. Basidiomycota is one of the two largest groups of fungi, characterized by the production of basidiospores on club-like structures called basidia. This group includes not only mushrooms but also puffballs, bracket fungi, and rusts. In ecosystems, Basidiomycota mushrooms function primarily as decomposers and symbionts, roles that are essential for nutrient cycling and plant health. Their ability to break down complex organic matter, such as lignin and cellulose, makes them key players in the carbon cycle, facilitating the release of nutrients back into the soil.

As decomposers, Basidiomycota mushrooms excel in breaking down dead plant material, including wood, leaves, and other organic debris. This process is particularly important in forests, where they contribute to the recycling of nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon. By decomposing lignin, a tough polymer found in plant cell walls, these fungi help convert woody material into humus, enriching soil fertility. Without such decomposers, ecosystems would be overwhelmed by dead organic matter, hindering nutrient availability for other organisms. This role underscores the importance of Basidiomycota mushrooms in maintaining the health and productivity of terrestrial ecosystems.

In addition to their decomposer role, Basidiomycota mushrooms form symbiotic relationships with plants, primarily through mycorrhizal associations. In these relationships, fungal hyphae extend into plant roots, enhancing the plant's ability to absorb water and nutrients, particularly phosphorus. In return, the plant provides the fungus with carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis. This mutualistic symbiosis is widespread, with an estimated 90% of plant species benefiting from mycorrhizal fungi. For example, many tree species in forests rely on Basidiomycota mushrooms to access nutrients in poor soils, highlighting their role in supporting plant growth and forest ecosystems.

Basidiomycota mushrooms also contribute to ecosystem resilience by fostering biodiversity. Their mycelial networks, often referred to as the "wood wide web," connect plants and trees, facilitating the transfer of nutrients and signaling molecules between them. This interconnectedness enhances the overall health and stability of ecosystems, enabling plants to withstand stressors such as drought or disease. Furthermore, mushrooms serve as a food source for various animals, including insects, mammals, and birds, thereby supporting higher trophic levels in food webs.

In conclusion, Basidiomycota mushrooms are indispensable components of ecosystems, functioning as both decomposers and symbionts. Their ability to break down complex organic matter and form mutualistic relationships with plants ensures nutrient cycling and supports plant health. By fostering biodiversity and resilience, these fungi play a critical role in maintaining the balance and productivity of ecosystems worldwide. Understanding their ecology not only highlights their importance but also emphasizes the need to conserve fungal habitats for the overall health of our planet.

Marinating Mushrooms: Restaurant Secrets for Succulent Fungi

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mushrooms belong to the fungal group known as Basidiomycetes.

Yes, all mushrooms are classified under the division Basidiomycota, which is one of the major groups of fungi.

Basidiomycetes are distinguished by their reproductive structures called basidia, which produce spores externally, unlike Ascomycetes that produce spores in sacs.

No, mushrooms belong to Basidiomycetes, while most yeasts and molds belong to the Ascomycetes or Zygomycetes groups.

While the majority of mushrooms are Basidiomycetes, a few belong to the Ascomycetes group, such as the morel and truffle mushrooms.