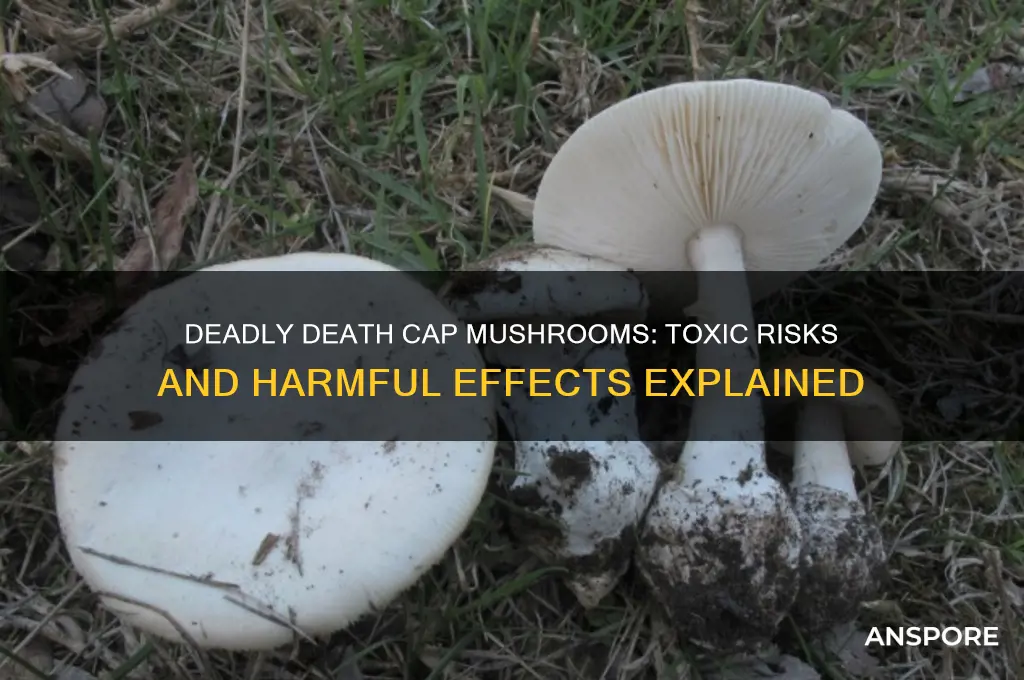

Death cap mushrooms (*Amanita phalloides*) are extremely toxic and pose a severe threat to human health. They contain potent toxins, including amatoxins, which can cause irreversible damage to the liver and kidneys, often leading to organ failure and, in many cases, death. Despite their innocuous appearance, consuming even a small amount of a death cap mushroom can result in symptoms such as severe abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, and dehydration, typically appearing 6 to 24 hours after ingestion. Due to their resemblance to edible mushrooms, accidental poisoning is common, making it crucial to avoid foraging for wild mushrooms without expert knowledge. Immediate medical attention is essential if ingestion is suspected, as prompt treatment can significantly improve survival rates.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Toxic Compound | Amatoxins (primarily α-Amanitin, β-Amanitin, and γ-Amanitin) |

| Lethal Dose | As little as 30 grams (1 ounce) of fresh mushroom or 10 grams (0.35 ounces) of dried mushroom |

| Symptoms (Early) | Delayed onset (6-24 hours): abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, dehydration |

| Symptoms (Late) | Liver and kidney failure, jaundice, seizures, coma, death (within 5-7 days without treatment) |

| Appearance | Greenish-yellow to yellowish-brown cap, white gills, bulbous base with cup-like volva, and ring on stem |

| Habitat | Found under oak, beech, and other hardwood trees in Europe, North America, and Asia |

| Misidentification Risk | Often mistaken for edible mushrooms like paddy straw mushrooms or caesar's mushroom |

| Treatment | Immediate medical attention, supportive care, liver transplant in severe cases |

| Fatality Rate | 10-50% without treatment; significantly lower with early intervention |

| Prevention | Avoid foraging without expert knowledge, cook all wild mushrooms thoroughly (though cooking does not destroy amatoxins) |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Amatoxins cause severe liver damage

The death cap mushroom, *Amanita phalloides*, contains amatoxins, a group of cyclic octapeptides that are among the most deadly toxins found in nature. These compounds are not destroyed by cooking, drying, or freezing, making them particularly insidious. Even a small amount—as little as half a mushroom cap—can cause severe liver damage in adults. For children, the toxic dose is even lower, emphasizing the critical need for awareness and prevention.

Amatoxins exert their destructive effects by targeting hepatocytes, the primary cells of the liver. They inhibit RNA polymerase II, a crucial enzyme for protein synthesis, leading to cell death. Symptoms of poisoning typically appear 6–24 hours after ingestion, starting with gastrointestinal distress (vomiting, diarrhea) and progressing to liver failure within 2–4 days. Without prompt medical intervention, mortality rates can exceed 50%. Early treatment, including activated charcoal, intravenous fluids, and, in severe cases, liver transplantation, is essential for survival.

Comparing amatoxin poisoning to other forms of liver damage highlights its unique severity. Unlike alcohol-induced cirrhosis or viral hepatitis, which develop over time, amatoxin toxicity causes rapid, acute liver failure. The liver’s regenerative capacity is overwhelmed, leading to systemic complications such as coagulopathy and encephalopathy. This underscores the importance of immediate medical attention if ingestion is suspected, even if symptoms are not yet present.

To minimize the risk of amatoxin exposure, practical precautions are vital. Foraging for wild mushrooms should only be done by experienced individuals who can reliably identify species. When in doubt, avoid consumption entirely. Educate children about the dangers of wild mushrooms and supervise outdoor activities in areas where death caps may grow. In case of accidental ingestion, save a sample of the mushroom for identification and seek emergency medical care immediately. Time is of the essence in mitigating the devastating effects of amatoxins.

Is Mushroom Compost Harmful or Helpful for Your Garden?

You may want to see also

Symptoms appear 6-24 hours after ingestion

The delayed onset of symptoms after ingesting death cap mushrooms is a sinister feature of their toxicity. Unlike many poisons that act swiftly, the toxins in these mushrooms, primarily amatoxins, operate insidiously. After consumption, the initial 6 to 24 hours may seem deceptively normal, lulling victims into a false sense of security. This latency period is crucial, as it often leads to delayed medical intervention, significantly worsening the prognosis. Understanding this timeline is vital for anyone who suspects accidental ingestion, as immediate action—even before symptoms appear—can be life-saving.

During this asymptomatic phase, the amatoxins are silently wreaking havoc on the liver and kidneys. These toxins inhibit RNA polymerase II, a critical enzyme for protein synthesis, leading to cellular death in these organs. The body’s initial lack of response is not a sign of safety but rather a reflection of the toxins’ slow-acting nature. For instance, a child who ingests even a small fragment of a death cap (as little as half a mushroom cap) could be in grave danger, yet they might remain symptom-free for up to a day. This makes early detection and treatment—such as gastric lavage or activated charcoal administration—essential, even if the individual feels fine.

The first symptoms to appear typically mimic common gastrointestinal issues: nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. These nonspecific signs often lead to misdiagnosis, with victims attributing them to food poisoning or a stomach bug. However, unlike typical gastrointestinal illnesses, these symptoms are just the prelude to more severe complications. Within 24 to 72 hours, as liver and kidney function deteriorates, jaundice, seizures, and coma can follow. Recognizing the initial symptoms as potential mushroom poisoning is critical, especially if there’s any history of wild mushroom consumption within the past day.

To navigate this dangerous window effectively, anyone who suspects ingestion of a death cap should immediately contact a poison control center or seek emergency medical care. Do not wait for symptoms to appear. Provide as much detail as possible about the mushroom’s appearance, the amount consumed, and the time of ingestion. In some cases, early administration of antidotes like silibinin or N-acetylcysteine can mitigate the toxins’ effects. For children or pets, who are at higher risk due to their smaller body mass, even a tiny amount warrants urgent action. Remember, the absence of immediate symptoms is not a sign of safety but a critical period for intervention.

Are Mushrooms Safe for Dogs? Risks and Precautions Explained

You may want to see also

No immediate taste or smell warning

One of the most insidious aspects of the death cap mushroom (*Amanita phalloides*) is its deceptive lack of immediate taste or smell warnings. Unlike many toxic substances that announce their danger through bitterness, acridity, or foul odors, the death cap is remarkably bland. This absence of sensory cues lulls foragers into a false sense of security, making it easy to mistake for edible varieties like the straw mushroom or young puffballs. The mushroom’s mild, slightly nutty flavor and pleasant aroma further disguise its lethal nature, ensuring that even a small bite can lead to severe poisoning.

Consider the mechanics of this deception: the toxins in the death cap, primarily amatoxins, are heat-stable and not volatile, meaning they neither alter the mushroom’s scent nor evaporate during cooking. This contrasts sharply with, say, poisonous plants like poison hemlock, which emit a rank odor when crushed. Foragers, especially inexperienced ones, may rely on taste or smell as a quick test of edibility, a practice that proves catastrophically ineffective with the death cap. A single cap contains enough amatoxins to kill an adult, yet its innocuous flavor profile offers no hint of the impending danger.

The lack of immediate warning signs complicates treatment, as victims often delay seeking medical help. Symptoms of amatoxin poisoning—nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain—typically appear 6 to 24 hours after ingestion, long after the mushroom has been digested. By then, the toxins have already begun damaging the liver and kidneys, often irreversibly. This delayed onset is a direct consequence of the mushroom’s deceptive nature, as victims assume their meal was safe based on its taste and smell. For children, who are more susceptible to poisoning due to their lower body weight, even a small fragment of a death cap can be fatal.

To mitigate this risk, foragers must adopt a zero-tolerance approach to identification. Never consume a wild mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its species, and cross-reference with multiple reliable guides or experts. Avoid relying on folklore tests, such as cooking with silver spoons or observing insect avoidance, as these are unreliable. If you suspect ingestion of a death cap, immediate medical intervention is critical. Activated charcoal may be administered within the first hour to reduce toxin absorption, but the most effective treatment is a liver transplant in severe cases.

In essence, the death cap’s lack of immediate taste or smell warning is a masterclass in evolutionary deception. It underscores the importance of knowledge over instinct in foraging and serves as a stark reminder that nature’s most dangerous creations often hide behind unassuming facades.

Supporting Through a Bad Trip: Compassionate Guidance for Mushroom Experiences

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$13.49 $16.02

Misidentification often leads to poisoning

The death cap mushroom, *Amanita phalloides*, is notorious for its deadly toxins, yet its unassuming appearance often leads to tragic misidentification. Foraging enthusiasts, especially those unfamiliar with mycology, may mistake it for edible species like the paddy straw mushroom (*Volvariella volvacea*) or the common button mushroom (*Agaricus bisporus*). This confusion is not merely a mistake—it’s a potentially fatal error. The death cap’s toxins, primarily amatoxins, are heat-stable and not destroyed by cooking, making even a small bite lethal. Understanding the subtle differences in cap color, gill structure, and the presence of a volva (a cup-like base) is critical to avoiding this deadly doppelgänger.

Consider the case of a family in California who, in 2016, mistook death caps for edible mushrooms, resulting in multiple organ failures and the need for liver transplants. This example underscores the importance of expert verification before consumption. Foragers should adhere to the rule: "If in doubt, throw it out." Additionally, carrying a detailed field guide or consulting a mycologist can prevent such tragedies. Children and pets are particularly at risk due to their curiosity and lower body mass, making even a tiny ingestion dangerous. Symptoms of poisoning, including abdominal pain, diarrhea, and vomiting, typically appear 6–24 hours after ingestion, by which time the toxins may have already caused irreversible damage.

To illustrate the challenge, compare the death cap to the edible straw mushroom. Both have a whitish cap and grow in similar habitats, but the death cap’s volva and bulbous base are telltale signs of its toxicity. The straw mushroom, on the other hand, lacks these features and has a smoother stem. Such distinctions are not always obvious to the untrained eye, especially in younger specimens where the volva may be less pronounced. Foraging courses or workshops can provide hands-on training to sharpen identification skills, emphasizing the adage that proper knowledge is the best antidote to misidentification.

Persuasively, the risks of misidentification far outweigh the rewards of foraging without expertise. While the thrill of finding wild mushrooms can be enticing, the consequences of a single mistake are dire. Amatoxins are so potent that as little as 50 grams of the death cap can be lethal to an adult. Even experienced foragers occasionally fall victim to its deceptive appearance, particularly in regions where it has been introduced, such as North America and Australia. Relying on digital apps or superficial similarities is insufficient; only thorough knowledge and caution can mitigate the risk.

In conclusion, misidentification of the death cap mushroom is a perilous yet preventable error. By prioritizing education, seeking expert guidance, and adopting a cautious approach, foragers can enjoy the bounty of nature without endangering themselves or others. The death cap’s allure lies in its innocuous appearance, but its true nature demands respect and vigilance. Remember: the forest floor is no place for guesswork.

How to Spot Spoiled Mushrooms: Key Signs of Decay

You may want to see also

Delayed treatment can be fatal

The death cap mushroom, or *Amanita phalloides*, contains amatoxins that cause severe liver and kidney damage. Symptoms often appear 6–24 hours after ingestion, starting with vomiting and diarrhea, which can misleadingly suggest a simple stomach bug. This delay in severe symptoms is particularly dangerous because it lulls victims into a false sense of security, causing them to postpone seeking medical help. By the time organ failure begins—typically 24–48 hours post-ingestion—the toxins may have already inflicted irreversible damage. Immediate treatment is critical; without it, mortality rates soar to 50% or higher, even in otherwise healthy adults.

Consider a scenario where a family forages mushrooms and mistakenly cooks death caps. A 30-year-old adult consumes a single mushroom, roughly 20–30 grams, enough to deliver a lethal dose of amatoxins. If they wait 12 hours to seek treatment, the toxins have already begun replicating in liver cells, disrupting protein synthesis and causing cell death. At this stage, activated charcoal—effective if administered within 1–2 hours of ingestion—is no longer useful. Instead, the patient requires intravenous fluids, N-acetylcysteine to counteract liver damage, and potentially a liver transplant. Delayed treatment reduces the effectiveness of these interventions, turning a survivable mistake into a fatal one.

Children are especially vulnerable due to their lower body weight. A 10-year-old ingesting even half a death cap mushroom could face life-threatening complications within 36 hours. Parents often mistake early symptoms for food poisoning, further delaying hospital visits. Pediatric cases require aggressive fluid management and close monitoring of liver enzymes, but these measures are far less effective if initiated after the child’s condition has deteriorated. Time is not just a factor here—it’s the decisive element between recovery and tragedy.

To minimize risk, anyone suspecting mushroom poisoning should follow these steps: first, preserve a sample of the mushroom for identification. Second, contact a poison control center or emergency services immediately, even if symptoms seem mild. Third, avoid home remedies or inducing vomiting unless instructed by a professional. Hospitals can administer silibinin, an antidote that blocks toxin absorption, but only if the patient arrives in time. Every hour counts; delaying treatment by as little as 6 hours can reduce survival odds dramatically.

Comparing death cap poisoning to other toxic ingestions highlights the urgency. For instance, lead poisoning or alcohol overdose allows days or weeks for intervention. Amatoxins, however, act swiftly and silently, making delayed treatment particularly catastrophic. While other poisonings may cause discomfort or long-term issues, death cap ingestion is uniquely time-sensitive. Recognizing this distinction could save lives, emphasizing the need for immediate action over cautious observation.

Four Sigmatic Mushroom Coffee: Uncovering Potential Health Concerns

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The entire death cap mushroom is toxic, including the cap, stem, gills, and spores. The toxins are evenly distributed throughout the mushroom.

Death cap mushrooms contain amatoxins, primarily alpha-amanitin, which are highly toxic to the liver and kidneys. These toxins can cause severe organ damage and failure.

No, cooking, boiling, or drying death cap mushrooms does not eliminate their toxicity. Amatoxins are heat-stable and remain dangerous even after preparation.

Symptoms include severe gastrointestinal distress (vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain), dehydration, liver and kidney failure, and in severe cases, death. Symptoms may appear 6–24 hours after ingestion.