Mushroom bodies are prominent neuropils found in annelids and in all arthropod groups except crustaceans. They were first identified in 1850 by French biologist Félix Dujardin, who called them corps pédonculés, comparing their appearance to the fruiting bodies of lichens. Mushroom bodies are best known for their role in olfactory associative learning and memory. They are composed of thousands of densely packed neurons called Kenyon cells, which receive and process sensory information to guide behaviour. The exact functions of specific neurons within mushroom bodies are still unclear, but they are extensively studied due to their distinct genetic makeup.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Description | Dense networks of neuronal processes (dendrite and axon terminals) and glia |

| Shape | Hemispherical calyx, a protuberance that is joined to the rest of the brain by a central nerve tract or peduncle |

| Composition | Kenyon cells, the intrinsic neurons of the mushroom bodies |

| Function | Olfactory associative learning, memory, sensory filtering, motor control, and place memory |

| Role in insects | The mushroom body is a unique structure for intervention in the insect brain |

| Notable species | Cockroach, honey bee, locust, fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster |

| Neurons | α/β, α’/β’, and γ neurons |

| Kenyon cells | 2000-2500 per hemisphere |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Mushroom bodies are neuropils

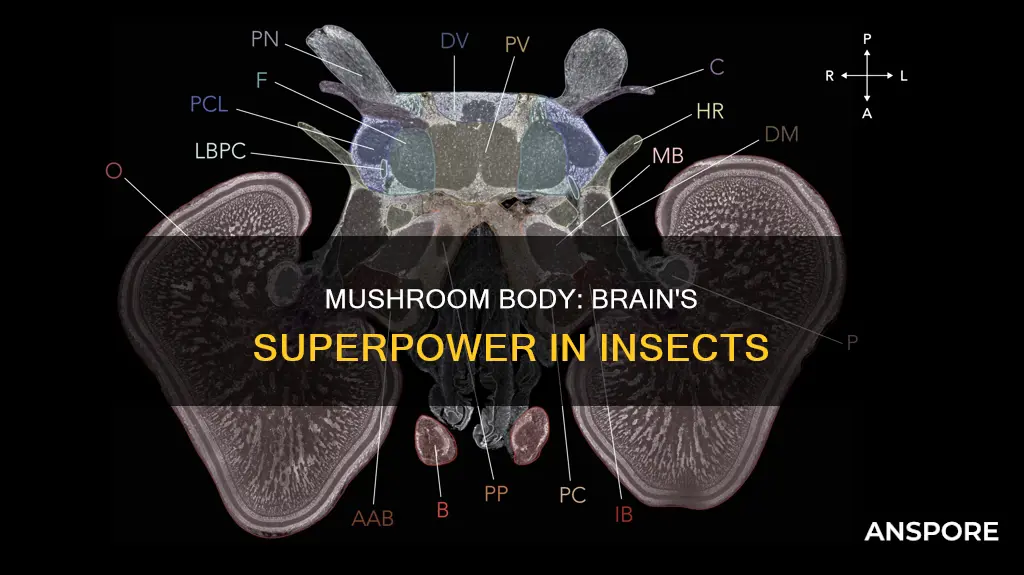

The mushroom body is a structure in the insect brain, with long, densely packed nerve fibres, or Kenyon cells, that run on either side of the central complex from back to front and downward through the protocerebrum. They are joined to the rest of the brain by a central nerve tract or peduncle. The peduncles of the mushroom bodies extend through the midbrain and are mainly composed of the long, densely packed nerve fibres of the Kenyon cells.

Mushroom bodies are best known for their role in olfactory associative learning. They receive olfactory signals from dopaminergic, octopaminergic, cholinergic, serotonergic, and GABAergic neurons outside the MB. However, their role likely extends beyond olfactory processing, as they are also found in anosmic primitive insects. Anatomical studies suggest they may also play a role in processing visual and mechanosensory input in some species.

Mushroom bodies have been found to have other learning and memory functions in larger insects, such as associative memory, sensory filtering, motor control, and place memory. They are thought to act as a coincidence detector, integrating multi-modal inputs and creating novel associations, thus contributing to learning and memory. Recent work also indicates that mushroom bodies are involved in innate olfactory behaviours through interactions with the lateral horn.

The exact roles of the specific neurons that make up mushroom bodies are still unclear. However, they are studied extensively due to their distinct genetic makeup. There are three specific classes of neurons that make up the mushroom body lobes: α/β, α’/β’, and γ neurons, each with distinct gene expression. Drosophila mushroom bodies are often used to study learning and memory due to their relatively discrete nature.

Mushrooms: Inulin-Rich Superfood for Gut Health

You may want to see also

They are involved in olfactory associative learning

The mushroom body is a distinct higher-order brain center in insect brains that is essential for olfactory learning and memory. It is a pair of structures located in the insect brain, and its function is primarily associated with olfaction, learning, and memory. The mushroom body is crucial for an insect's survival as it enables them to learn and remember odors associated with rewards, such as food sources or mates, and odors that signal dangers, such as predators. This ability to associate odors with positive or negative experiences is known as olfactory associative learning.

Insects rely heavily on their sense of smell to navigate their environment, find food, and recognize mates. Olfactory associative learning involves forming connections between a specific odor and a positive or negative experience. When an insect encounters an odor, the sensory input is processed by the antenna and transmitted to the mushroom body. The mushroom body then integrates this olfactory information with other sensory inputs and plays a crucial role in the learning and memory processes.

The mushroom body is composed of multiple cell types, including Kenyon cells, which are unique to insects. These Kenyon cells receive input from olfactory sensory neurons and transmit output to various brain regions. During olfactory associative learning, the Kenyon cells undergo plastic changes, forming new connections or modifying existing ones. These changes are believed to underlie the insect's ability to remember and differentiate between different odors and their associated experiences.

The mushroom body is also involved in higher-order processing, including the ability to form concepts and generalize learned information. For example, after learning to associate a particular odor with a reward, insects can generalize this learning to similar but not identical odors. This demonstrates a level of cognitive flexibility and abstraction mediated by the mushroom body. Furthermore, the mushroom body is implicated in regulating an insect's response to odors based on internal states, such as hunger or thirst, further emphasizing its role in complex olfactory behaviors.

The function of the mushroom body in olfactory associative learning has been extensively studied in various insect species, particularly fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster), which have become a model organism for understanding memory and behavior. Through genetic manipulation and behavioral assays, scientists have been able to identify specific genes and neural circuits within the mushroom body that contribute to learning and memory formation. This knowledge has provided valuable insights into the neural basis of learning and memory, not only in insects but also with potential implications for understanding cognitive processes in other animals, including humans.

In summary, the mushroom body is integral to an insect's survival and adaptation to its environment through its involvement in olfactory associative learning. Its ability to process and integrate olfactory information, undergo plastic changes, and mediate complex behaviors highlights the importance of this brain structure in the fascinating world of insect cognition and behavior.

Magic Mushrooms: Potent Power or Placebo?

You may want to see also

They are present in all arthropods except crustaceans

The mushroom body is a distinct higher-order brain structure found in insects and other arthropods, playing a crucial role in sensory integration, particularly in olfactory learning and memory. Its name derives from its shape, which resembles a mushroom. While the mushroom body is a prominent feature in most arthropods, it is notably absent in crustaceans, setting them apart from other arthropod groups in terms of brain organization and function.

The presence of mushroom bodies is indeed a common trait among arthropods, a diverse group of invertebrates that includes insects, spiders, centipedes, and crustaceans. Arthropods have long been recognized for their sophisticated behaviors, and the mushroom body is thought to be a key factor in their ability to process complex information and exhibit advanced cognitive abilities. However, crustaceans, which include animals such as crabs, lobsters, shrimp, and barnacles, do not possess this particular brain structure.

The absence of mushroom bodies in crustaceans suggests that they have evolved distinct neural architectures to accomplish similar cognitive tasks. Crustaceans are known for their complex behaviors, including advanced social interactions, tool use, and even problem-solving abilities. While they lack the dedicated olfactory processing center found in other arthropods, they have developed alternative brain structures that facilitate these complex behaviors. This divergence in brain organization highlights the diverse evolutionary paths that different arthropod groups have taken to achieve similar cognitive capabilities.

One key difference between crustaceans and other arthropods is the presence of a structure known as the olfactory lobe in the former. The olfactory lobe serves a similar function to the mushroom body in that it processes olfactory information and plays a role in learning and memory. However, the olfactory lobe is not structurally or developmentally equivalent to the mushroom body, indicating that it has evolved independently in crustaceans as a solution to similar sensory processing challenges. This unique aspect of crustacean brain anatomy showcases the adaptability and diversity of nervous system organization within the arthropod phylum.

The absence of mushroom bodies in crustaceans provides valuable insights into the plasticity and adaptability of arthropod nervous systems. It demonstrates that while certain brain structures may be prevalent across a wide range of species, there is no single, universal blueprint for achieving complex cognitive functions. The variation in brain organization between crustaceans and other arthropods highlights the dynamic nature of neural evolution, where different structures can be modified or recruited to fulfill similar functional roles. This diversity in brain design is a testament to the incredible adaptability and complexity of the animal kingdom.

In conclusion, the mushroom body, a distinctive brain structure in arthropods, is absent in crustaceans, marking a significant variation in brain anatomy within this diverse phylum. Crustaceans have evolved alternative neural pathways and structures, such as the olfactory lobe, to process sensory information and perform complex tasks. This exception underscores the fascinating adaptability and diversity of arthropod nervous systems, providing valuable insights into the myriad ways nature has devised to tackle the challenges of survival and cognition.

Dancing Mushroom: Where is the Elusive Fun?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

They are made up of Kenyon cells

Mushroom bodies are neuropils, or dense networks of neuronal processes and glia. They are found in annelids and all arthropod groups except crustaceans. They were first identified in 1850 and are believed to be responsible for an arthropod's intelligence and ability to execute voluntary actions. They are particularly prominent in the Hymenoptera order of insects, which includes bees, ants, and wasps.

Mushroom bodies are made up of Kenyon cells, which are a type of neuron. These cells are long and densely packed, and they project axons that form the mushroom body lobes. In flies, there are 2000–2500 Kenyon cells per hemisphere. The Kenyon cells are activated by odourant molecules that bind to receptors on the insect's antennae. Different odours activate different sets of Kenyon cells, and this activation is unique to each individual.

The Kenyon cells then activate output neurons, which convey signals to other parts of the brain. This process is believed to be how mushroom bodies support olfactory associative learning. They may also be involved in other types of learning and memory functions, such as associative memory, sensory filtering, motor control, and place memory. For example, studies have shown that mushroom bodies are involved in fat storage homeostasis in fruit flies. Silencing certain Kenyon cells that project into the α’β’ lobes decreases de novo fatty acid synthesis and causes leanness, while hyperactivating these cells causes overfeeding and obesity.

The exact functions of the mushroom body and its Kenyon cells are still not fully understood, and the topic is currently being researched. However, it is clear that they play an important role in the brain's processing of sensory information and in learning and memory.

Starchy Veggies: Are Mushrooms Part of This Group?

You may want to see also

They are involved in memory formation

Mushroom bodies are networks of neuronal processes and glia found in the insect brain. They are involved in memory formation, particularly in olfactory associative learning. Fruit flies, for example, can learn to approach odours that have been previously paired with food and avoid odours that have been paired with an electric shock. This process is believed to be mediated by the mushroom body.

The mushroom body is composed of Kenyon cells, which are activated by odour molecules binding to receptors on the fly's antennae. These Kenyon cells then activate output neurons that convey signals to other parts of the brain. The Kenyon cells are thought to be involved in short- and middle-term memory of odours in flies.

In larger insects, studies suggest that mushroom bodies have other learning and memory functions, such as associative memory, sensory filtering, motor control, and place memory. They are believed to act as coincidence detectors, integrating multi-modal inputs and creating novel associations, thus contributing to their role in learning and memory.

Recent research has also implicated mushroom bodies in the regulation of fat storage in fruit flies. By manipulating the neural activity of different portions of the mushroom body, scientists observed that silencing certain neurons led to decreased fatty acid synthesis and leanness, while hyperactivating the same neurons caused overfeeding and obesity. This discovery highlights the potential involvement of mushroom bodies in metabolic processes and homeostasis.

Effective Sprays to Keep Mushrooms Healthy and Happy

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mushroom bodies are dense networks of neuronal processes (dendrite and axon terminals) and glia. They are found in the brains of insects and some other arthropods.

Mushroom bodies are believed to be involved in learning and memory functions, such as associative memory, sensory filtering, motor control, and place memory. They are also thought to play a role in integrating multi-modal inputs and creating novel associations.

Mushroom bodies receive olfactory signals from various types of neurons outside the MB. They then activate output neurons that convey signals to other parts of the brain.

Mushroom bodies provide insight into the circuitry that supports learning and memory. They also help us understand how specific circuits of brain cells enable animals to respond to their environment.