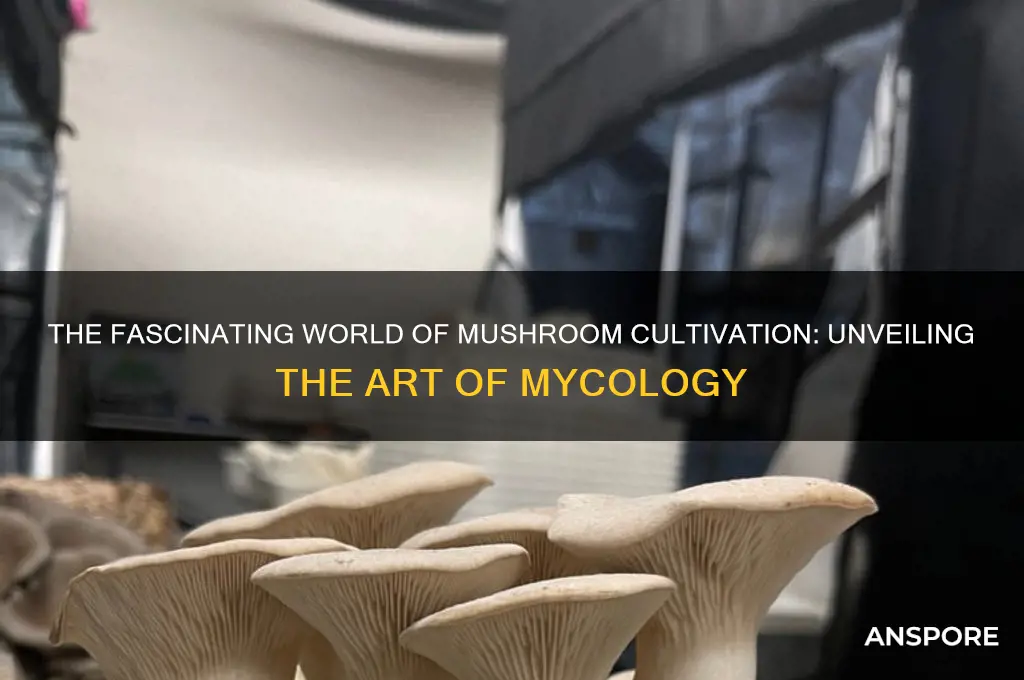

The art of growing mushrooms, known as myciculture, is a fascinating and specialized practice that involves cultivating fungi under controlled conditions. Derived from the Greek words mykes (fungus) and culture, myciculture encompasses techniques for nurturing various mushroom species, from culinary favorites like shiitake and oyster mushrooms to medicinal varieties such as reishi and lion's mane. This discipline requires a deep understanding of fungal biology, environmental factors, and substrate preparation to ensure optimal growth. Whether pursued as a hobby, a commercial venture, or for scientific research, myciculture highlights the intricate relationship between humans and fungi, offering both sustenance and ecological benefits.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Mycology Basics: Study of fungi, including mushrooms, their biology, and ecological roles

- Mushroom Cultivation: Techniques for growing mushrooms commercially or at home

- Substrates & Spawn: Materials and methods for mushroom growth mediums

- Species Selection: Choosing mushroom varieties for specific climates and purposes

- Harvesting & Storage: Proper techniques to ensure quality and longevity of mushrooms

Mycology Basics: Study of fungi, including mushrooms, their biology, and ecological roles

The art of growing mushrooms is called fungiculture, a practice deeply rooted in the broader scientific discipline of mycology. Mycology is the study of fungi, a diverse group of organisms that includes mushrooms, yeasts, molds, and more. While fungiculture focuses on the cultivation techniques and processes, mycology provides the foundational knowledge of fungal biology, ecology, and taxonomy that underpins successful mushroom cultivation. Understanding mycology basics is essential for anyone interested in fungiculture, as it equips cultivators with the knowledge to optimize growth conditions, identify species, and appreciate the ecological roles of fungi.

Fungi are unique organisms that play critical roles in ecosystems. Unlike plants, they lack chlorophyll and cannot produce their own food through photosynthesis. Instead, fungi obtain nutrients by decomposing organic matter, forming symbiotic relationships with plants (mycorrhizae), or acting as parasites. Mushrooms, the fruiting bodies of certain fungi, are reproductive structures that release spores to propagate the species. Mycology explores these biological processes, shedding light on how fungi interact with their environment and contribute to nutrient cycling, soil health, and biodiversity. This knowledge is vital for fungiculture, as it informs decisions about substrate selection, environmental conditions, and pest management.

The biology of fungi is another key area of mycological study. Fungi are eukaryotic organisms with cell walls composed of chitin, a feature that distinguishes them from plants and animals. Their growth is influenced by factors such as temperature, humidity, pH, and light. Mycologists investigate fungal metabolism, reproduction, and genetics to understand how these organisms adapt to different environments. For fungiculture, this knowledge is applied to create optimal growing conditions, such as maintaining specific humidity levels or using particular substrates to support mycelial growth and mushroom fruiting.

Ecologically, fungi are indispensable. As decomposers, they break down complex organic materials like wood, leaves, and dead organisms, returning nutrients to the soil and supporting plant growth. Mycorrhizal fungi form mutualistic relationships with plant roots, enhancing nutrient uptake and improving plant health. Some fungi even act as biological control agents, suppressing pathogens and pests. In fungiculture, recognizing these ecological roles helps cultivators adopt sustainable practices, such as using organic substrates or integrating mushrooms into agroecosystems to improve soil fertility.

Finally, mycology provides tools for identifying and classifying fungal species, a critical skill for fungiculture. With over 140,000 described species of fungi and potentially millions more yet to be discovered, accurate identification ensures that cultivators work with the right species for their goals. Mycologists use morphological characteristics, molecular techniques, and ecological data to classify fungi. For fungiculture, this knowledge prevents the cultivation of toxic or non-productive species and allows for the selection of varieties with desirable traits, such as high yield, flavor, or medicinal properties.

In summary, mycology serves as the scientific foundation for fungiculture, offering insights into fungal biology, ecology, and taxonomy. By understanding mycology basics, cultivators can apply this knowledge to grow mushrooms more effectively, sustainably, and safely. Whether for food, medicine, or ecological restoration, the synergy between mycology and fungiculture highlights the importance of studying fungi in all their complexity.

Mushrooms in Mulch: Are They Safe for Your Plants?

You may want to see also

Mushroom Cultivation: Techniques for growing mushrooms commercially or at home

The art of growing mushrooms is called mycology, specifically focusing on fungiculture when referring to the cultivation process. Whether you're growing mushrooms commercially or at home, understanding the techniques and principles of mushroom cultivation is essential for success. Mushroom cultivation involves creating the ideal environment for fungal growth, from substrate preparation to harvesting. Below are detailed techniques to guide you through the process.

Substrate Preparation: The Foundation of Mushroom Cultivation

The substrate is the material on which mushrooms grow, providing nutrients and a structure for mycelium (the vegetative part of the fungus) to colonize. Common substrates include straw, sawdust, wood chips, and grain, depending on the mushroom species. For example, oyster mushrooms thrive on straw, while shiitake mushrooms prefer sawdust. The substrate must be pasteurized or sterilized to eliminate competing microorganisms. Pasteurization involves soaking the substrate in hot water (around 60-70°C) for an hour, while sterilization requires autoclaving at 121°C for 1-2 hours. Proper substrate preparation ensures a healthy and productive mushroom crop.

Spawn Inoculation: Introducing the Mycelium

Once the substrate is prepared, it is inoculated with mushroom spawn, which is mycelium grown on a carrier material like grain. The spawn introduces the fungus to the substrate, allowing it to colonize and eventually produce mushrooms. For small-scale or home cultivation, pre-made spawn can be purchased from suppliers. Commercial growers often produce their own spawn to reduce costs. After inoculation, the substrate is placed in a dark, humid environment to encourage mycelium growth. This stage, known as spawning or incubation, typically takes 2-4 weeks, depending on the species and conditions.

Fruiting Conditions: Triggering Mushroom Growth

Once the substrate is fully colonized by mycelium, it is time to induce fruiting. This involves exposing the colonized substrate to conditions that mimic the mushroom's natural environment. Key factors include light, humidity, temperature, and fresh air exchange. For example, oyster mushrooms require temperatures between 18-25°C, high humidity (85-95%), and indirect light. Shiitake mushrooms prefer cooler temperatures (12-18°C) and slightly lower humidity. Fruiting chambers or grow rooms are often used to control these conditions. Misting the substrate or using humidifiers can maintain the necessary moisture levels, while proper ventilation prevents the buildup of carbon dioxide.

Harvesting and Post-Harvest Care

Mushrooms are ready to harvest when the caps are fully open but before the gills release spores. Harvesting is done by gently twisting or cutting the mushrooms at the base. Proper timing ensures the best flavor, texture, and shelf life. After harvesting, mushrooms should be stored in a cool, dry place or refrigerated to extend freshness. For commercial growers, post-harvest handling includes cleaning, sorting, and packaging for distribution. Home growers can enjoy their harvest fresh or preserve them by drying, freezing, or pickling.

Scaling Up: Commercial Mushroom Cultivation

Commercial mushroom cultivation requires a larger-scale approach, often involving specialized equipment and facilities. Growers may use tiered shelving systems to maximize space, automated climate control systems, and bulk substrate preparation methods. Consistent quality and yield are critical for profitability. Commercial operations also focus on sustainability, recycling spent substrate as compost or animal feed. Additionally, growers must adhere to food safety regulations and market demands, often cultivating popular varieties like button, cremini, and portobello mushrooms.

By mastering these techniques, both home growers and commercial cultivators can successfully practice the art of mushroom cultivation. Whether for personal enjoyment or business, the process is rewarding and offers a deeper appreciation for the fascinating world of fungi.

Profitable Mushroom Farming: A Comprehensive Guide to Growing for Business

You may want to see also

Substrates & Spawn: Materials and methods for mushroom growth mediums

The art of growing mushrooms is called mycology, specifically fungiculture when referring to the cultivation process. In fungiculture, the choice and preparation of substrates and spawn are critical to successful mushroom growth. Substrates serve as the nutrient base for mushrooms, while spawn acts as the inoculant, introducing the mushroom mycelium to the substrate. Understanding the materials and methods for preparing these growth mediums is essential for any cultivator.

Substrates are the materials on which mushrooms grow, providing the necessary nutrients, moisture, and structure for mycelium development. Common substrates include straw, wood chips, sawdust, compost, and grain. The choice of substrate depends on the mushroom species being cultivated. For example, oyster mushrooms thrive on straw, while shiitake mushrooms prefer sawdust or wood chips. Preparation of substrates often involves sterilization or pasteurization to eliminate competing microorganisms. Sterilization, typically done in an autoclave or pressure cooker, is crucial for grain-based substrates to ensure a clean environment for mycelium growth. Pasteurization, a less intense process, is suitable for bulk substrates like straw and involves soaking the material in hot water to reduce microbial activity.

Spawn is the material colonized by mushroom mycelium and is used to inoculate the substrate. It comes in various forms, including grain spawn, sawdust spawn, and plug spawn. Grain spawn, made by colonizing grains like rye or wheat with mycelium, is widely used due to its versatility and ease of handling. Sawdust spawn is often used for wood-loving mushrooms, while plug spawn consists of wooden dowels inoculated with mycelium, commonly used for outdoor cultivation in logs. Preparing spawn requires a sterile environment to prevent contamination. This is typically done in a clean workspace or laminar flow hood, where sterilized grains or other materials are inoculated with mushroom culture or liquid culture.

The method of combining substrates and spawn varies depending on the cultivation technique. In the spawn-to-substrate approach, pre-pasteurized or sterilized substrate is mixed with grain spawn in a controlled environment. This mixture is then placed in grow bags or trays, where the mycelium colonizes the substrate. For outdoor cultivation, such as in logs or wood chips, plug spawn or sawdust spawn is inserted directly into pre-drilled holes, allowing the mycelium to expand naturally. Monitoring humidity, temperature, and airflow during colonization is crucial to ensure optimal growth conditions.

Advanced cultivators may experiment with supplemented substrates, which include additional nutrients like gypsum, limestone, or nitrogen sources to enhance mushroom yield and quality. For instance, casing layers—a mixture of peat moss, vermiculite, and lime—are often applied to the surface of colonized substrates in agaricus (button mushroom) cultivation to trigger fruiting. Understanding the specific needs of each mushroom species and tailoring the substrate and spawn accordingly is key to successful fungiculture.

In summary, mastering substrates and spawn involves selecting the right materials, employing proper preparation techniques, and understanding the unique requirements of different mushroom species. Whether using simple straw-based substrates or complex supplemented mediums, the goal is to create an environment where mycelium can thrive and produce abundant mushrooms. With careful attention to detail and a bit of practice, cultivators can turn the art of fungiculture into a rewarding and productive endeavor.

Unveiling the Mystery: Mushrooms Sprouting on Your Lawn Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Species Selection: Choosing mushroom varieties for specific climates and purposes

The art of growing mushrooms is called mycology, specifically fungiculture when referring to the cultivation process. When selecting mushroom species for cultivation, it is crucial to consider both the climate and the intended purpose, as these factors significantly influence success and yield. Different mushroom varieties thrive in specific environmental conditions, and understanding these requirements ensures optimal growth and productivity.

Climate Considerations are paramount in species selection. For instance, oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) are highly adaptable and can grow in a wide range of temperatures (50°F to 80°F), making them ideal for temperate climates. In contrast, lion's mane mushrooms (Hericium erinaceus) prefer cooler temperatures (55°F to 70°F) and are better suited for regions with mild, consistent climates. Tropical climates favor species like shiitake mushrooms (Lentinula edodes), which thrive in warm, humid conditions (60°F to 80°F with high humidity). For colder regions, enoki mushrooms (Flammulina velutipes) are a suitable choice, as they can tolerate temperatures as low as 35°F. Understanding the temperature, humidity, and seasonal variations of your climate is essential for selecting a species that will flourish.

Purpose-Driven Selection is equally important. If the goal is culinary use, species like button mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus) or portobello mushrooms are popular due to their versatility and widespread appeal. For medicinal purposes, reishi (Ganoderma lucidum) and chaga (Inonotus obliquus) are highly valued for their immune-boosting properties. Environmental remediation is another purpose, where species like oyster mushrooms excel at breaking down lignin and cellulose, making them useful for mycoremediation projects. Additionally, decorative or ornamental purposes might lead to the selection of turkey tail mushrooms (Trametes versicolor), known for their vibrant colors and patterns.

Substrate Compatibility must also be considered when choosing mushroom species. Different mushrooms require specific growing mediums. For example, shiitake mushrooms grow best on hardwood logs, while oyster mushrooms can thrive on straw, coffee grounds, or sawdust. Button mushrooms prefer composted manure, and lion's mane often requires supplemented sawdust or wood-based substrates. Matching the species to the available substrate ensures efficient nutrient uptake and healthy growth.

Finally, disease resistance and growth rate are practical factors in species selection. Fast-growing species like oyster mushrooms are ideal for beginners or commercial growers seeking quick yields. Conversely, reishi and lion's mane have longer growth cycles but offer higher market value due to their medicinal benefits. Selecting disease-resistant varieties, such as shiitake, can reduce the risk of crop failure, especially in humid environments where mold and bacteria are prevalent. By carefully evaluating these factors, growers can choose mushroom varieties that align with their climate, purpose, and resources, ensuring a successful and rewarding cultivation experience.

Do Death Cap Mushrooms Grow in Wisconsin? A Toxic Fungus Guide

You may want to see also

Harvesting & Storage: Proper techniques to ensure quality and longevity of mushrooms

The art of growing mushrooms is called mycology, specifically fungiculture when referring to the cultivation of fungi. Harvesting and storing mushrooms properly is crucial to maintaining their quality, flavor, and shelf life. Below are detailed techniques to ensure the best results.

Harvesting Techniques for Optimal Quality

Harvesting mushrooms at the right time is essential to ensure they are at their peak flavor and texture. For most varieties, such as button, shiitake, or oyster mushrooms, harvest when the caps are fully open but before the gills or pores begin to drop spores. This stage ensures the mushrooms are mature yet still firm. To harvest, gently twist or use a sharp knife to cut the mushroom at the base of the stem, avoiding pulling or damaging the surrounding mycelium. Damaged mushrooms spoil quickly, so handle them with care. Regularly inspect your growing area to catch mushrooms at the ideal stage, as some varieties can deteriorate rapidly if left too long.

Post-Harvest Handling and Preparation

After harvesting, clean the mushrooms minimally to preserve their freshness. Brush off dirt or debris with a soft brush or cloth instead of washing them, as excess moisture can accelerate spoilage. If washing is necessary, do so quickly under cold water and pat the mushrooms dry immediately. Trim any discolored or damaged parts of the mushroom to prevent decay from spreading. For varieties with tough stems, such as shiitakes, consider removing the stems before storage or cooking, as they can become woody over time.

Short-Term Storage Solutions

For short-term storage (up to a week), place harvested mushrooms in a breathable container, such as a paper bag or a loosely closed cardboard box, to maintain humidity while allowing air circulation. Avoid plastic bags, as they trap moisture and promote mold growth. Store the mushrooms in the refrigerator at temperatures between 2°C and 4°C (36°F to 39°F). If you need to store them for a few days longer, wrap the mushrooms in a paper towel to absorb excess moisture before placing them in the refrigerator.

Long-Term Storage Methods

For long-term storage, drying or freezing are the most effective methods. To dry mushrooms, clean them thoroughly and slice them evenly. Lay the slices on a dehydrator tray or a baking sheet in an oven set to a low temperature (around 60°C or 140°F) until completely dry. Store dried mushrooms in an airtight container in a cool, dark place for up to a year. For freezing, blanch the mushrooms in hot water for 2-3 minutes, then plunge them into ice water to halt cooking. Drain and pat them dry before placing them in freezer-safe bags or containers. Frozen mushrooms can last up to 12 months and are best used in cooked dishes.

Monitoring and Maintaining Quality

Regularly inspect stored mushrooms for signs of spoilage, such as mold, sliminess, or off odors. Proper storage conditions and prompt use of harvested mushrooms are key to preserving their quality. Label stored mushrooms with the date of harvest to track their freshness. By following these harvesting and storage techniques, you can enjoy your homegrown mushrooms at their best, whether used immediately or saved for later culinary creations.

Cold's Impact: Does It Speed Up or Slow Down Mushroom Growth?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The art of growing mushrooms is called mycology when referring to the scientific study of fungi, but the specific practice of cultivating mushrooms is often referred to as mushroom cultivation or fungiculture.

Mushroom cultivation differs from traditional gardening because mushrooms are fungi, not plants. It involves specific techniques like sterilizing substrates, maintaining humidity, and controlling temperature, making it a unique practice known as fungiculture.

The art of growing mushrooms requires knowledge of mycology, understanding of fungal life cycles, sterilization techniques, and the ability to create and maintain optimal growing conditions such as humidity, temperature, and light.

Yes, mushroom cultivation can be done at home through practices like home fungiculture. It often involves using grow kits, sterilized substrates, and controlled environments to cultivate mushrooms like oyster, shiitake, or button mushrooms.

The art of growing mushrooms dates back thousands of years, with ancient civilizations like the Egyptians and Chinese practicing fungiculture. Modern techniques have evolved, but the core principles of cultivating mushrooms remain rooted in traditional methods.