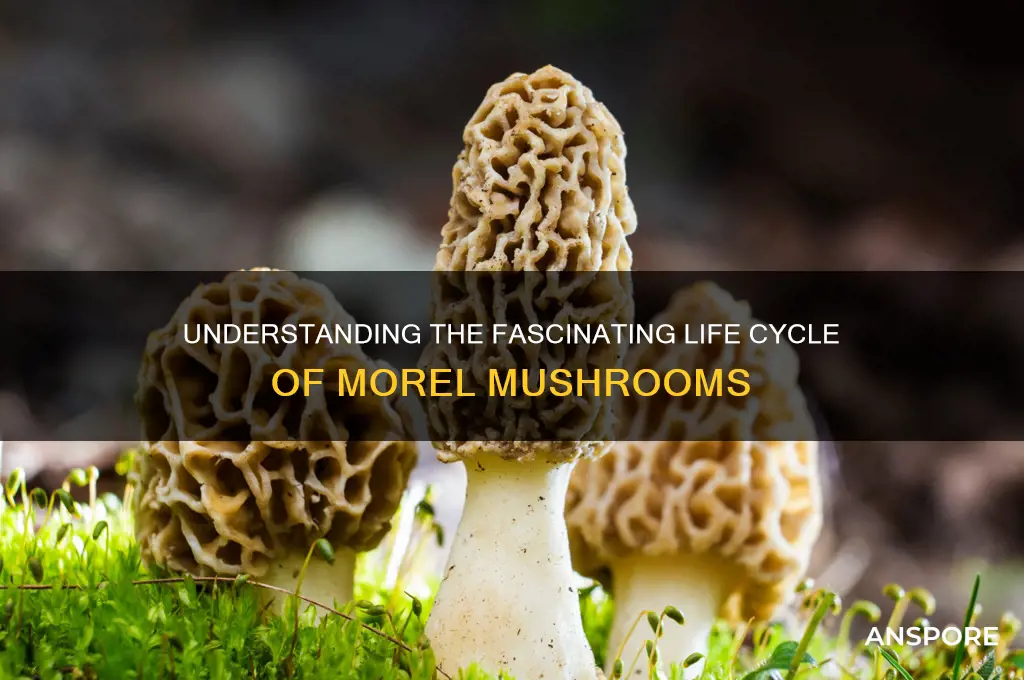

The life cycle of a morel mushroom is a fascinating and complex process that involves several distinct stages. Beginning with the dispersal of spores from mature mushrooms, these microscopic units land on suitable substrates and germinate under optimal conditions of moisture and temperature. The spores develop into thread-like structures called hyphae, which form a network known as mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus. Over time, the mycelium grows and colonizes organic matter, often forming symbiotic relationships with trees or decomposing plant material. When environmental conditions are just right—typically in spring with adequate moisture and warming soil temperatures—the mycelium aggregates and differentiates into the fruiting bodies we recognize as morel mushrooms. These fruiting bodies release spores, completing the cycle and ensuring the continuation of the species. Understanding this life cycle is crucial for both foragers and cultivators, as it highlights the delicate balance of factors required for morel growth and sustainability.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spores and Dispersal: Morel spores are released into the air, carried by wind, and land in suitable habitats

- Germination and Mycelium: Spores germinate, forming mycelium networks that grow underground, absorbing nutrients from soil

- Fruiting Conditions: Specific environmental cues (temperature, moisture) trigger mycelium to produce fruiting bodies (morels)

- Growth and Development: Morel mushrooms emerge from the ground, growing rapidly over 1-2 weeks to maturity

- Spore Release and Decay: Mature morels release spores, then decompose, returning nutrients to the soil and cycle

Spores and Dispersal: Morel spores are released into the air, carried by wind, and land in suitable habitats

Morel mushrooms begin their life cycle with spore dispersal, a process as delicate as it is vital. Unlike plants that rely on seeds, morels depend on microscopic spores, each a potential new fungus. These spores are produced in vast quantities within the mushroom’s cap, housed in structures called asci. When mature, the asci rupture, releasing spores into the air with a precision that ensures maximum dispersal. This mechanism is nature’s way of guaranteeing that at least some spores will find their way to environments conducive to growth, despite the odds stacked against them.

Wind becomes the spores’ silent ally, carrying them across forests, fields, and even urban areas. This passive dispersal method is both efficient and unpredictable, allowing morels to colonize new habitats far from their parent mushroom. However, wind dispersal is a double-edged sword. While it increases the chances of finding suitable soil, it also means many spores will land in inhospitable environments—dry ground, water bodies, or areas lacking the necessary symbiotic partners. For foragers and cultivators, understanding this randomness underscores the challenge of predicting where morels will appear each season.

Once a spore lands in a suitable habitat, its success hinges on specific conditions. Morel spores thrive in environments with well-draining, slightly acidic soil, often enriched with decaying hardwood trees like elm, ash, or oak. The presence of symbiotic bacteria and specific soil fungi further enhances their chances of germination. For those attempting to cultivate morels, mimicking these conditions is crucial. Amending soil with wood chips or leaves and maintaining a pH between 6.0 and 7.0 can increase the likelihood of spore germination. However, even with optimal conditions, success is not guaranteed, as morels remain notoriously finicky in cultivation.

The journey from spore to mushroom is a testament to resilience and adaptability. After germination, the spore develops into a network of thread-like structures called mycelium, which can remain dormant in the soil for years, waiting for the right conditions to fruit. This latent period highlights the morel’s strategy of patience, ensuring survival through unfavorable seasons. For foragers, this means that areas with a history of morel sightings are worth revisiting, as the mycelium may still be present, biding its time. Cultivators, meanwhile, must exercise patience, as it can take multiple seasons for spores to establish and produce mushrooms.

In the end, the dispersal of morel spores is a fascinating blend of chance and precision. While wind carries them far and wide, their success is ultimately determined by the delicate interplay of soil, climate, and symbiosis. For those captivated by these elusive fungi, whether as foragers or cultivators, understanding this process is key. It’s a reminder that nature’s strategies are often as unpredictable as they are ingenious, and that the life cycle of the morel is as much about persistence as it is about growth.

Preserve Saffron Milk Cap Mushrooms: Easy Freezing Guide for Freshness

You may want to see also

Germination and Mycelium: Spores germinate, forming mycelium networks that grow underground, absorbing nutrients from soil

The life cycle of a morel mushroom begins with a microscopic yet monumental event: spore germination. These spores, dispersed by mature mushrooms, land on the forest floor and, under optimal conditions, awaken from dormancy. This process is highly dependent on environmental cues such as moisture, temperature, and soil composition. Once activated, a spore develops into a hypha, a thread-like structure that serves as the foundation for the mycelium network. This initial stage is critical, as it marks the transition from a dormant state to an active, growing organism.

As hyphae extend and branch out, they form an intricate mycelium network that spreads underground. This network is the morel’s primary means of nutrient absorption, extracting organic matter, minerals, and water from the soil. The mycelium acts like a subterranean root system, though far more complex and efficient. It can cover vast areas, sometimes spanning several meters, to maximize resource acquisition. This phase is often likened to the "invisible workhorse" of the morel’s life cycle, as it occurs out of sight but is essential for the mushroom’s eventual fruiting.

Practical considerations for fostering healthy mycelium growth include maintaining soil moisture levels between 50-70% and ensuring a pH range of 6.0 to 7.5, as morels thrive in slightly acidic to neutral conditions. Incorporating organic matter like wood chips or leaf litter can enhance nutrient availability and mimic the mushroom’s natural habitat. Avoid compacting the soil, as mycelium requires oxygen to thrive. For cultivators, using a sterile substrate inoculated with morel spawn can accelerate mycelium development, though patience is key—this stage can take months to years, depending on environmental conditions.

Comparatively, the mycelium phase of morels differs from other fungi in its specificity and longevity. Unlike fast-growing species like oyster mushrooms, morel mycelium often requires a symbiotic relationship with tree roots (mycorrhizal association) to flourish. This interdependence underscores the importance of preserving forest ecosystems for successful morel cultivation. Additionally, while some fungi produce visible signs of mycelium, such as mold-like growths, morel mycelium remains largely hidden, making its health difficult to assess without careful observation of soil conditions and fruiting patterns.

In conclusion, the germination of spores and subsequent mycelium formation are foundational steps in the morel’s life cycle, setting the stage for future fruiting bodies. By understanding and supporting this phase through proper soil management and environmental conditions, enthusiasts can increase their chances of a successful harvest. This underground network is not just a biological process but a testament to the resilience and complexity of nature’s design.

Can Dogs Eat Mushrooms?

You may want to see also

Fruiting Conditions: Specific environmental cues (temperature, moisture) trigger mycelium to produce fruiting bodies (morels)

Morel mushrooms, those prized delicacies of the forest floor, don't simply spring into existence. Their emergence is a carefully orchestrated dance with the environment, a symphony of cues that signal to the hidden mycelium network it's time to fruit.

The Triggering Duo: Temperature and Moisture

Imagine a thermostat and a rain gauge dictating the fate of a gourmet meal. For morels, specific temperature ranges and moisture levels act as the key that unlocks their fruiting potential. Generally, soil temperatures between 50-60°F (10-15°C) are the sweet spot, mimicking the cool, damp conditions of spring in many temperate regions. This temperature range, coupled with consistent moisture, awakens the dormant mycelium, prompting it to divert energy from vegetative growth into the production of those coveted fruiting bodies.

Think of it as a biological alarm clock. Just as a certain temperature and light level signal to plants it's time to bloom, morels have their own internal calendar, set by these environmental cues.

The Moisture Factor: A Delicate Balance

Moisture is the other critical player in this fungal drama. Too little, and the mycelium remains dormant, conserving energy. Too much, and the risk of rot and disease skyrockets. Ideal moisture levels for morel fruiting typically fall between 60-80% soil saturation. This translates to a damp, spongy feel to the soil, not waterlogged or soggy.

Pro Tip: Experienced foragers often look for areas where snowmelt or spring rains have recently saturated the ground, creating the perfect moisture gradient for morel emergence.

Beyond the Basics: The Symphony of Cues

While temperature and moisture are the primary conductors, other environmental factors contribute to the fruiting symphony. Changes in day length, pH levels, and even the presence of specific tree species can influence morel fruiting. Some species, like the yellow morel, have a symbiotic relationship with certain trees, relying on their root systems for nutrients and signals.

Understanding these complex interactions is key to predicting morel blooms and cultivating these elusive fungi.

The Takeaway: Patience and Observation

Successfully finding or cultivating morels requires a deep understanding of these environmental cues and a healthy dose of patience. It's a game of waiting for the right temperature window, the perfect moisture balance, and the subtle signs that the mycelium is ready to reveal its hidden treasure. By observing the natural world and respecting the intricate dance of nature, we can unlock the secrets of these delicious and enigmatic mushrooms.

Harvesting Mushrooms: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Growth and Development: Morel mushrooms emerge from the ground, growing rapidly over 1-2 weeks to maturity

Morel mushrooms burst from the forest floor with surprising speed, their honeycomb caps unfurling in a matter of days. This rapid growth, typically spanning 1-2 weeks, is a testament to the fungus's efficient utilization of resources. Unlike many mushrooms that take weeks or even months to mature, morels capitalize on the fleeting window of spring, when soil temperatures and moisture levels are optimal. This accelerated development is crucial for their survival strategy, allowing them to produce and disperse spores before the onset of summer heat and dryness.

Imagine a time-lapse of a morel's growth: a tiny, egg-like structure pushing through the leaf litter, then a rapid expansion as the cap unfolds, revealing its intricate network of ridges and pits. This process is fueled by the mushroom's mycelium, a vast underground network of thread-like filaments that has been silently gathering nutrients for months or even years. When conditions are right, the mycelium redirects its energy towards fruiting, resulting in the sudden appearance of these prized mushrooms.

This rapid growth phase is not without its vulnerabilities. Morel mushrooms are highly sensitive to environmental fluctuations during this period. A sudden drop in temperature, a lack of rainfall, or competition from other fungi can stunt their development or even cause them to abort fruiting altogether. Foraging enthusiasts must be mindful of these factors, as they directly impact the availability and quality of morels in any given season.

Understanding this delicate balance between rapid growth and environmental sensitivity is key to appreciating the ephemeral nature of morel mushrooms and the skill required to successfully harvest them.

Mastering Mushroom Preparation: A Simple Guide to Steaming Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Spore Release and Decay: Mature morels release spores, then decompose, returning nutrients to the soil and cycle

Mature morels, having fulfilled their reproductive purpose, initiate a critical phase in their life cycle: spore release and decay. This process begins when the mushroom’s cap dries out, causing the honeycomb-like pits and ridges to split open. As air currents or physical disturbances pass through, millions of microscopic spores are ejected into the environment. Each spore is a potential new morel, carrying genetic material to colonize new areas. This dispersal mechanism is both efficient and essential, ensuring the species’ survival across diverse habitats.

Once spore release is complete, the morel’s structure begins to decompose. This decay is not a failure but a deliberate step in the cycle. As the mushroom breaks down, it returns vital nutrients—such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon—to the soil. These elements, absorbed from the environment during the morel’s growth, are now recycled to nourish surrounding plants and microorganisms. This process highlights the morel’s role as a decomposer, contributing to the health and fertility of its ecosystem.

Practical observation of this phase can be instructive for foragers and mycologists alike. Foragers should note that mature, spore-releasing morels are past their prime for consumption, as their texture becomes dry and brittle. Instead, focus on harvesting younger, firmer specimens. Mycologists, on the other hand, can study this stage to understand spore viability and dispersal patterns, which are crucial for cultivation efforts. For example, placing a mature morel on a dark surface and gently tapping it can reveal the cloud of spores released, a simple yet effective field test.

Comparatively, the decay of morels contrasts with the longevity of their underground mycelial network, which can persist for years. While the fruiting body is ephemeral, the mycelium remains, storing energy and waiting for optimal conditions to produce new mushrooms. This duality underscores the morel’s life cycle as a balance between visible, short-lived reproduction and invisible, long-term survival strategies. By studying this phase, we gain insight into the mushroom’s resilience and its integral role in nutrient cycling.

In conclusion, spore release and decay are not endpoints but transformative stages in the morel’s life cycle. They ensure genetic continuity and ecological contribution, turning what appears to be death into renewal. For anyone interested in morels—whether for foraging, cultivation, or ecological study—understanding this phase is key to appreciating the mushroom’s full impact on its environment. Observe, respect, and learn from this process, as it embodies the morel’s role as both a creator and a recycler in the forest ecosystem.

Reishi Mushrooms: A Rich Source of Vitamin D?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The life cycle of a morel mushroom consists of four main stages: spore germination, mycelium growth, fruiting body formation, and spore release.

Morel mushrooms reproduce through the release of spores from their mature fruiting bodies. These spores are dispersed by wind or water and germinate under suitable conditions to start a new life cycle.

Mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus, grows underground or in decaying organic matter, absorbing nutrients and forming a network. It is essential for the development of the fruiting bodies (morels) when conditions are favorable.

Morels require specific conditions to complete their life cycle, including moist soil, moderate temperatures (typically 50–70°F or 10–21°C), and a symbiotic relationship with certain trees. Adequate organic matter and proper pH levels are also crucial.