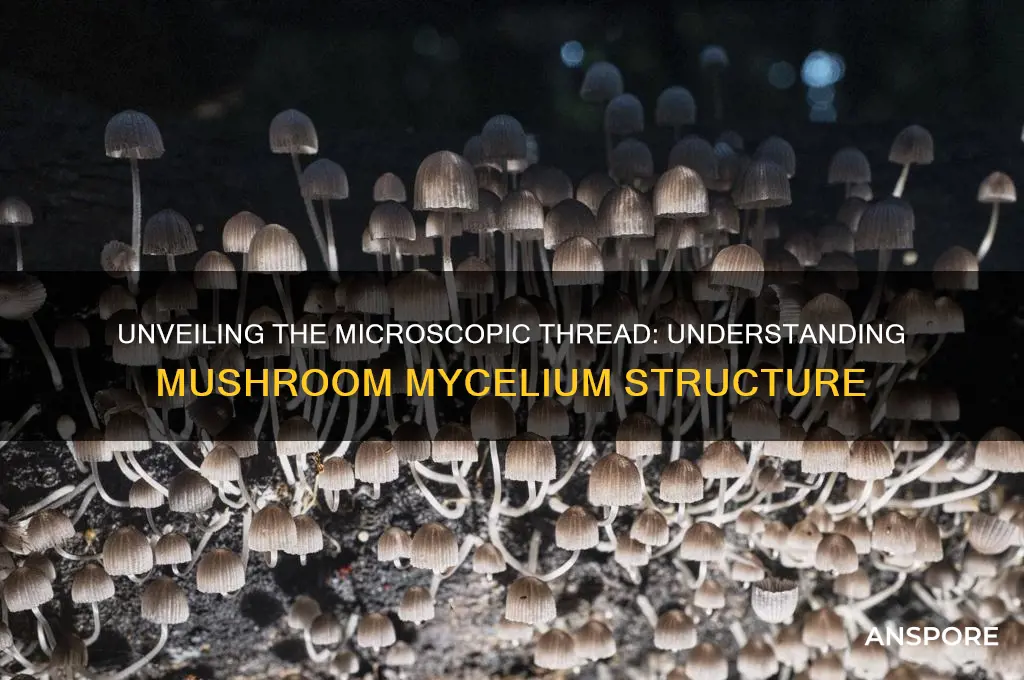

Mushrooms, fascinating organisms in the fungi kingdom, are composed of various intricate structures, and one of the most crucial components is the thread-like network called mycelium. This dense, often invisible web of filaments forms the vegetative part of the fungus, playing a vital role in nutrient absorption and growth. While the mushroom itself is the fruiting body we commonly see, it is the mycelium that truly sustains the organism, making it the unsung hero of the fungal world. Understanding what this thread is called—mycelium—opens the door to appreciating the complex and essential role it plays in ecosystems and beyond.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Hyphal Structure: Mushrooms are composed of thread-like structures called hyphae, which form the mycelium network

- Mycelium Function: Mycelium absorbs nutrients, supports growth, and connects mushrooms in their ecosystem

- Hyphal Types: Hyphae can be septate (with cross-walls) or coenocytic (without cross-walls), depending on species

- Role in Decomposition: Hyphae break down organic matter, recycling nutrients in the environment

- Hyphal Growth: Hyphae grow at their tips, extending the mycelium network through soil or substrate

Hyphal Structure: Mushrooms are composed of thread-like structures called hyphae, which form the mycelium network

Mushrooms, often celebrated for their culinary and medicinal properties, owe their existence to a hidden, intricate network of thread-like structures called hyphae. These microscopic filaments are the building blocks of the fungal world, forming the mycelium—a vast, underground web that sustains the mushroom’s life cycle. Hyphae are not merely structural components; they are dynamic, living entities that absorb nutrients, transport water, and communicate with their environment. Understanding their role reveals the remarkable complexity behind these seemingly simple organisms.

Analytically, hyphae function as the fungal equivalent of plant roots, but with a unique twist. Unlike roots, which grow from a central point, hyphae extend in all directions, branching and fusing to create a dense, interconnected network. This mycelium can span acres, making it one of nature’s most efficient systems for nutrient acquisition. For example, a single cubic inch of soil can contain miles of hyphae, highlighting their unparalleled ability to explore and exploit resources. This efficiency is why fungi are often the first organisms to colonize nutrient-poor environments, such as decaying wood or contaminated soil.

From a practical standpoint, harnessing the power of hyphae has transformative potential. In agriculture, mycelium networks can enhance soil health by breaking down organic matter and releasing nutrients in plant-available forms. Gardeners can encourage this process by incorporating mushroom compost or inoculating soil with mycelium cultures. For instance, adding oyster mushroom mycelium to a garden bed can improve soil structure and nutrient cycling, leading to healthier plants. Similarly, in mycoremediation—the use of fungi to clean up pollutants—hyphae are employed to absorb heavy metals and break down toxins, offering a sustainable solution to environmental contamination.

Comparatively, the hyphal structure of mushrooms contrasts sharply with the cellular organization of plants and animals. While plants rely on rigid cell walls for support and animals on specialized tissues for function, fungi use flexible, tubular hyphae to adapt to their surroundings. This adaptability allows fungi to thrive in diverse habitats, from forest floors to human bodies. For example, the mycelium of *Cordyceps* species can infiltrate insect hosts, demonstrating the versatility of hyphal growth. Such comparisons underscore the unique evolutionary path of fungi, shaped by their reliance on hyphae.

Descriptively, the mycelium network is a marvel of natural engineering. Each hypha is a hollow tube, lined with a chitinous cell wall that provides strength without sacrificing flexibility. As hyphae grow, they secrete enzymes to dissolve surrounding organic matter, absorbing nutrients directly through their cell walls. This process is both precise and relentless, enabling fungi to decompose even the toughest materials, like lignin in wood. The result is a symbiotic relationship with the ecosystem, where fungi recycle nutrients and support the growth of other organisms. Observing this process under a microscope reveals a bustling, microscopic world, where hyphae pulse with life and purpose.

In conclusion, the hyphal structure of mushrooms is not just a biological curiosity but a cornerstone of fungal biology with practical implications. By understanding and leveraging hyphae, we can improve agriculture, remediate polluted environments, and even develop new materials, such as mycelium-based packaging. The thread-like hyphae, though invisible to the naked eye, weave the fabric of fungal life and offer solutions to some of our most pressing challenges. Their study is a testament to the power of the small and the unseen in shaping the world around us.

Creamy Mushroom Pappardelle: A Simple, Hearty Pasta Recipe to Try

You may want to see also

Mycelium Function: Mycelium absorbs nutrients, supports growth, and connects mushrooms in their ecosystem

Beneath the forest floor, a hidden network thrives—a labyrinth of threads called mycelium, the unsung hero of mushroom ecosystems. This intricate web, often likened to the internet of the natural world, performs vital functions that sustain not just mushrooms but entire habitats. Mycelium, the vegetative part of fungi, operates as a nutrient highway, a structural scaffold, and a communication channel, all in one.

Consider the nutrient absorption process: mycelium secretes enzymes that break down organic matter—dead leaves, wood, even toxins—into digestible compounds. This efficiency rivals industrial composting, turning waste into nourishment. For instance, mycelium can decompose lignin, a complex polymer in wood, which most organisms cannot process. This ability not only feeds the mushroom but also enriches the soil, making it a cornerstone of ecosystem health. Gardeners can harness this by incorporating mycelium-rich compost into beds to enhance nutrient availability for plants.

Structural support is another critical role. Mycelium acts as a living trellis, anchoring mushrooms and providing the framework for their growth. This is particularly evident in species like lion’s mane or oyster mushrooms, where the mycelium’s strength allows for robust fruiting bodies. In cultivation, mycelium is often grown on substrates like sawdust or grain, which it colonizes to form a dense, supportive matrix. For home growers, ensuring proper substrate moisture (around 60%) and temperature (20-25°C) optimizes mycelium development, leading to healthier mushrooms.

Perhaps most fascinating is mycelium’s role as a connector. It forms mycorrhizal networks, linking plants and trees in a symbiotic exchange of nutrients and signals. This underground internet allows trees to share resources and warn each other of threats, such as pests or drought. In forests, up to 90% of plants are interconnected via mycelium, highlighting its role as an ecosystem engineer. Land managers can promote this connectivity by preserving fungal habitats and minimizing soil disturbance, fostering resilience in natural systems.

In essence, mycelium is not just the thread that makes up mushrooms—it’s the lifeblood of their world. By absorbing nutrients, supporting growth, and fostering connections, it sustains mushrooms and their ecosystems. Whether in the wild or in cultivation, understanding and nurturing mycelium unlocks its potential to heal soils, support biodiversity, and even inspire innovations in materials and medicine. This hidden network reminds us that the most profound impacts often come from what lies beneath the surface.

Rich Giblet Gravy Recipe: Cream of Mushroom Twist for Holiday Feasts

You may want to see also

Hyphal Types: Hyphae can be septate (with cross-walls) or coenocytic (without cross-walls), depending on species

Mushrooms, those enigmatic organisms that straddle the line between plant and animal, are primarily composed of a network of thread-like structures called hyphae. These hyphae are the building blocks of fungal bodies, collectively known as the mycelium. But not all hyphae are created equal. Depending on the species, hyphae can exhibit distinct structural features, particularly in the presence or absence of cross-walls, known as septa. This distinction divides hyphae into two primary types: septate and coenocytic. Understanding these types sheds light on fungal diversity, function, and even potential applications in biotechnology.

Septate hyphae, characterized by the presence of cross-walls, are a hallmark of many mushroom-forming fungi, or basidiomycetes. These septa are not mere barriers; they are perforated, allowing for the regulated flow of nutrients, signaling molecules, and organelles between adjacent cellular compartments. This compartmentalization offers several advantages. For instance, it limits the spread of damage or toxins within the mycelium, enhancing the fungus’s resilience. Septate hyphae also facilitate more efficient resource allocation, as nutrients can be directed to areas of active growth or sporulation. A practical example is the shiitake mushroom (*Lentinula edodes*), whose septate hyphae contribute to its robust growth and nutrient-rich fruiting bodies. For cultivators, ensuring optimal conditions—such as a pH range of 5.5 to 6.5 and a temperature of 22–28°C—can maximize the benefits of this hyphal structure.

In contrast, coenocytic hyphae lack septa, forming long, continuous cells with multiple nuclei. This structure is common in zygomycetes and certain ascomycetes. The absence of cross-walls allows for rapid, unrestricted movement of cytoplasm and nuclei, which can be advantageous in nutrient-poor environments. However, this comes at a cost: damage or infection in one part of the hypha can spread more easily throughout the entire structure. For example, the black bread mold (*Rhizopus stolonifer*) relies on coenocytic hyphae to quickly colonize its substrate, but this also makes it more vulnerable to environmental stressors. Gardeners dealing with mold infestations should act swiftly, as the coenocytic nature of these fungi enables rapid spread under favorable conditions (high humidity, temperatures above 25°C).

The choice between septate and coenocytic hyphae reflects evolutionary adaptations to specific ecological niches. Septate hyphae are often associated with complex, multicellular fungi that form mushrooms, while coenocytic hyphae are more common in simpler, fast-growing species. This distinction has practical implications, particularly in biotechnology. For instance, septate hyphae are favored in mycelium-based packaging materials due to their structural integrity and compartmentalized damage control. Conversely, coenocytic hyphae are explored in enzyme production, where rapid growth and high metabolic activity are prioritized. Researchers working with fungal enzymes, such as amylases or proteases, often select coenocytic species like *Aspergillus niger* for their ability to produce large quantities of enzymes quickly.

In conclusion, the structural differences between septate and coenocytic hyphae are not merely academic curiosities but have tangible impacts on fungal biology and applications. Whether you’re a mushroom cultivator, a biotechnologist, or simply curious about the natural world, understanding these hyphal types can deepen your appreciation for the diversity and utility of fungi. By tailoring conditions to the specific needs of each hyphal type—whether it’s maintaining optimal pH for septate fungi or controlling humidity for coenocytic species—you can harness their unique strengths effectively.

Perfect Steak and Mushroom Subs: Easy Recipe for Juicy, Flavorful Sandwiches

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role in Decomposition: Hyphae break down organic matter, recycling nutrients in the environment

The thread-like structures that compose mushrooms are called hyphae, and they are the unsung heroes of decomposition. These microscopic filaments form a vast network known as the mycelium, which acts as the mushroom’s root system. Hyphae secrete enzymes that break down complex organic materials like cellulose, lignin, and chitin—components of plant and animal matter that are otherwise difficult to decompose. This process transforms dead organisms into simpler compounds, making hyphae essential for nutrient cycling in ecosystems.

Consider the forest floor, where fallen leaves, branches, and dead animals accumulate. Without hyphae, this organic matter would pile up, locking nutrients away from living organisms. Instead, hyphae infiltrate these materials, dissolving them into sugars, amino acids, and minerals. These nutrients are then absorbed by the mycelium and either used for fungal growth or released back into the soil, where they become available to plants and other organisms. This recycling process is critical for soil fertility and ecosystem health.

To understand the scale of this role, imagine a single cubic inch of soil containing miles of hyphae. This dense network ensures that decomposition occurs efficiently, even in environments where bacteria and other decomposers struggle. For example, hyphae can break down wood, a task few other organisms can accomplish. In agricultural settings, farmers can enhance soil health by encouraging mycelial growth through practices like mulching or using fungal inoculants. This not only improves nutrient availability but also reduces the need for synthetic fertilizers.

However, the effectiveness of hyphae in decomposition depends on environmental conditions. Optimal moisture, temperature, and pH levels are crucial for enzymatic activity. For instance, hyphae thrive in moist, cool environments, which is why they are particularly active in forests and grasslands. In arid or polluted areas, their activity may be hindered, slowing nutrient cycling. Gardeners and land managers can support hyphae by maintaining these conditions, such as by watering consistently and avoiding chemical pesticides that harm fungal communities.

In conclusion, hyphae are the driving force behind nature’s recycling system. By breaking down organic matter, they ensure that nutrients are continuously circulated, sustaining life in ecosystems. Whether in a forest, garden, or agricultural field, fostering healthy mycelial networks is key to maintaining soil fertility and ecological balance. Understanding and supporting this process can lead to more sustainable practices in both natural and managed environments.

Crafting Perfect Grain Jars for Mushroom Cultivation: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Hyphal Growth: Hyphae grow at their tips, extending the mycelium network through soil or substrate

Mushrooms, those enigmatic organisms that sprout overnight in forests and gardens, are not solitary entities but part of a vast, hidden network. The thread-like structures that compose this network are called hyphae, and their growth is a marvel of nature. Hyphae grow exclusively at their tips, a process known as apical growth, which allows them to extend the mycelium—the collective network of hyphae—through soil, wood, or other substrates. This growth mechanism is not just efficient but also strategic, enabling fungi to explore and exploit resources with precision.

Consider the mycelium as the internet of the fungal world, with hyphae acting as the cables connecting nodes. Each hyphal tip is a microscopic pioneer, secreting enzymes to break down organic matter and absorbing nutrients to sustain the network. This process is remarkably energy-efficient, as the fungus allocates resources solely to the growing tips rather than maintaining the entire structure. For instance, in a single gram of soil, there can be kilometers of hyphae, all working in unison to decompose matter and recycle nutrients.

To visualize hyphal growth, imagine a spider spinning a web, but instead of silk, it uses living cells that elongate and branch out. The tip of each hypha contains a vesicle—a small organelle—that directs growth by sensing environmental cues like nutrient availability or physical barriers. When a tip encounters a food source, it accelerates growth in that direction, while other tips may slow down or stop. This adaptive behavior ensures the mycelium maximizes its reach and resource acquisition.

Practical applications of understanding hyphal growth abound. In agriculture, mycelium networks improve soil health by enhancing nutrient cycling and water retention. For example, inoculating soil with specific fungi can increase crop yields by up to 30%. In bioremediation, hyphae are used to break down pollutants like oil spills or heavy metals, thanks to their ability to secrete powerful enzymes. Even in construction, mycelium-based materials are being developed as sustainable alternatives to Styrofoam, leveraging the strength and flexibility of the hyphal network.

To harness hyphal growth effectively, consider these tips: maintain optimal moisture levels (50-70% humidity) for mycelium cultivation, as hyphae require water to transport nutrients; avoid compacting the substrate, as air pockets facilitate hyphal extension; and monitor temperature (20-25°C) to encourage rapid but controlled growth. Whether you’re a gardener, scientist, or innovator, understanding how hyphae grow at their tips unlocks the potential of these microscopic threads to transform industries and ecosystems alike.

Simple Steps to Brew Delicious Mushroom Tea at Home

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The thread-like structure that makes up mushrooms is called mycelium.

No, mycelium is the underground network of filaments that supports the mushroom, which is the fruiting body that appears above ground.

The individual thread of mycelium is called a hypha (plural: hyphae).

Yes, all mushrooms are part of a larger organism composed of mycelium, which is essential for their growth and nutrient absorption.

Yes, mycelium can exist and grow without producing mushrooms, as it primarily functions to absorb nutrients and expand its network.