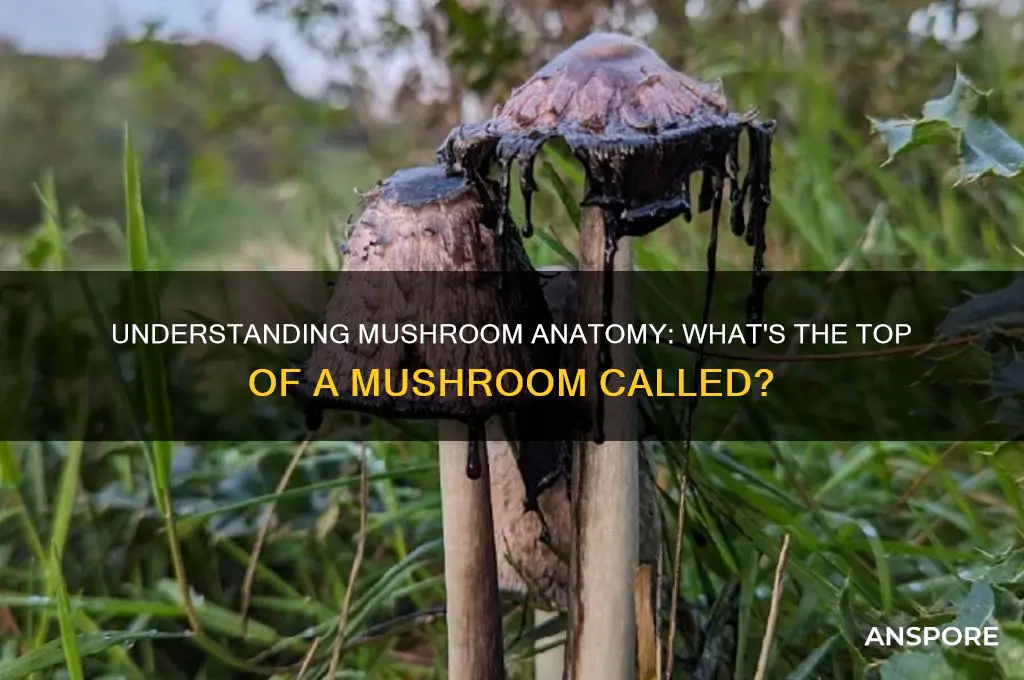

The top of a mushroom, often the most visually striking part, is called the cap. This structure is crucial for the mushroom's identification and plays a significant role in its reproductive process. The cap's shape, color, and texture can vary widely among different species, making it a key feature for mycologists and foragers alike. Beneath the cap, the gills or pores are typically found, which produce and release spores, ensuring the mushroom's propagation. Understanding the cap's characteristics not only aids in distinguishing edible mushrooms from toxic ones but also deepens our appreciation for the fascinating world of fungi.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Name | Pileus |

| Description | The top of a mushroom, often umbrella-shaped |

| Function | Protects the gills or pores underneath; aids in spore dispersal |

| Texture | Can vary from smooth to scaly, slimy, or fibrous |

| Color | Varies widely (e.g., white, brown, red, yellow) depending on species |

| Shape | Typically convex, but can be flat, bell-shaped, or irregular |

| Size | Ranges from a few millimeters to over 30 cm in diameter |

| Margins | May be curved inward (involute), flat, or curved outward (revolute) |

| Surface | Can be dry, sticky, or viscid; may have warts, scales, or fibers |

| Transparency | Some species have translucent or striate margins |

| Attachment | Attached to the stipe (stem) centrally, laterally, or not at all |

| Spore Bearing | Houses the gills, pores, or spines where spores are produced |

| Ecological Role | Key in identification and classification of mushroom species |

Explore related products

$16.97 $26.59

What You'll Learn

- Umbonate vs. Non-umbonate: Distinguishes mushrooms with a raised center (umbo) from those without

- Shape Variations: Includes convex, flat, or depressed caps, affecting identification

- Color Significance: Cap color often indicates species, habitat, or maturity stage

- Texture Types: Smooth, scaly, or slimy textures help classify mushroom varieties

- Margin Features: Characteristics like striations or curling edges aid in identification

Umbonate vs. Non-umbonate: Distinguishes mushrooms with a raised center (umbo) from those without

The top of a mushroom, known as the pileus or cap, exhibits various shapes and structures that are crucial for identification. One key feature used to distinguish mushrooms is the presence or absence of a raised central structure called the umbo. Mushrooms with a distinct, elevated center are termed umbonate, while those without such a feature are classified as non-umbonate. This distinction is fundamental in mycology, as it helps in categorizing mushrooms based on their morphological characteristics. Understanding whether a mushroom is umbonate or non-umbonate provides valuable insights into its species and potential uses or hazards.

Umbonate mushrooms are characterized by their prominent umbo, which can range from a slight bump to a sharp, nipple-like projection at the center of the cap. This feature is often inherited from the mushroom's button stage, where the umbo is more pronounced. Examples of umbonate mushrooms include the iconic Amanita muscaria (fly agaric), known for its bright red cap with a distinct umbo, and the Boletus edulis (porcini), which often has a rounded umbo. The umbo's presence can also influence the mushroom's texture and color distribution, making it a key identifier in the field. For foragers and mycologists, recognizing an umbonate cap is essential for accurate species identification.

In contrast, non-umbonate mushrooms lack a raised central structure, resulting in a flat, convex, or depressed cap. These mushrooms often have a more uniform surface, with no noticeable bump or projection. Examples include the Agaricus bisporus (button mushroom), which has a smooth, even cap, and the Pleurotus ostreatus (oyster mushroom), known for its fan-like, non-umbonate shape. Non-umbonate mushrooms are diverse in their forms, ranging from flat caps to deeply convex ones, but they all share the absence of a central umbo. This characteristic simplifies their identification, especially when compared to their umbonate counterparts.

The distinction between umbonate and non-umbonate mushrooms is not merely academic; it has practical implications for foraging and culinary uses. Umbonate mushrooms often have a more robust structure, which can affect their texture when cooked. For instance, the umbo of a porcini mushroom remains firm even after cooking, adding a unique mouthfeel to dishes. Non-umbonate mushrooms, on the other hand, tend to have a more delicate cap, making them ideal for slicing or sautéing. Understanding this difference allows chefs and foragers to select the right mushroom for specific recipes or preservation methods.

In summary, the terms umbonate and non-umbonate refer to the presence or absence of a raised center (umbo) on a mushroom's cap. Umbonate mushrooms feature a distinct central projection, while non-umbonate mushrooms have a flat or evenly curved cap. This distinction is vital for accurate identification, foraging, and culinary applications. By mastering this morphological difference, enthusiasts can deepen their appreciation of the diverse world of mushrooms and make informed decisions in both the field and the kitchen.

Infected Mushroom Pusher: Ableton 10 Compatibility

You may want to see also

Shape Variations: Includes convex, flat, or depressed caps, affecting identification

The top of a mushroom is called the cap, and its shape is a critical feature for identification. Mushroom caps exhibit a range of shapes, primarily categorized as convex, flat, or depressed. These variations are not merely aesthetic but serve as key diagnostic traits for mycologists and foragers alike. Understanding these shape differences is essential, as they can distinguish between edible, medicinal, and toxic species. For instance, a convex cap, which is rounded and dome-like, is common in many edible mushrooms, such as the button mushroom (*Agaricus bisporus*). In contrast, a flat cap, which appears level or slightly uplifted at the edges, is characteristic of species like the oyster mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*). Depressed caps, which are sunken in the center, are seen in mushrooms such as the shaggy mane (*Coprinus comatus*). Each shape variation provides clues about the mushroom's habitat, growth stage, and taxonomic classification.

Convex caps are among the most recognizable shapes in the fungal kingdom. They typically start as a rounded, bell-like structure in young mushrooms and may flatten with age. This shape is often associated with gills or pores underneath, which are crucial for spore dispersal. Convex caps are prevalent in the genus *Agaricus* and *Boletus*, where they contribute to the classic "toadstool" appearance. When identifying mushrooms with convex caps, observers should note additional features such as color, texture, and margin characteristics, as these can further narrow down the species. For example, a convex cap with a smooth, white surface and pink gills is a strong indicator of the edible meadow mushroom (*Agaricus campestris*).

Flat caps represent another significant shape variation, often observed in mature mushrooms or species that grow in clusters. This shape is characterized by a level surface, sometimes with slightly uplifted edges, resembling a plate or saucer. Flat caps are common in wood-decomposing fungi, such as the oyster mushroom, which grows in shelf-like formations on trees. The flat shape maximizes the surface area for spore release, making it an efficient adaptation for certain ecological niches. When identifying flat-capped mushrooms, pay attention to the attachment point (whether central or off-center) and the presence of any unusual features, such as ridges or zones of color, which can aid in species determination.

Depressed caps are less common but equally important for identification. These caps have a central depression, often resembling a funnel or shallow bowl. This shape is typical in species like the shaggy mane and certain *Clitocybe* mushrooms. The depressed form can be an indicator of maturity or environmental stress, as it may develop from a convex cap over time. Foragers should be cautious with depressed-capped mushrooms, as some toxic species, such as the deadly *Galerina* genus, may exhibit this shape. Always cross-reference depressed caps with other features, such as spore color and habitat, to ensure accurate identification.

In summary, the shape of a mushroom's cap—whether convex, flat, or depressed—is a fundamental characteristic that significantly influences identification. Each shape variation is associated with specific ecological roles, growth stages, and taxonomic groups. By carefully observing and documenting cap shape alongside other features, such as color, texture, and gill structure, enthusiasts can enhance their ability to accurately identify mushroom species. This knowledge not only supports scientific study but also promotes safe foraging practices, ensuring that the beauty and utility of fungi are appreciated without risk.

Mushroom Spore Syringes: Expiry and Longevity

You may want to see also

Color Significance: Cap color often indicates species, habitat, or maturity stage

The top of a mushroom is called the cap, and its color is a critical feature for identification, often revealing insights into the species, habitat, or maturity stage. Cap color is not merely a visual trait but a biological indicator shaped by evolutionary adaptations and environmental factors. For instance, brightly colored caps in species like the Fly Agaric (*Amanita muscaria*) serve as a warning to predators about toxicity, while earth-toned caps in species like the Chanterelle (*Cantharellus cibarius*) help them blend into forest floors. Understanding these color variations is essential for foragers, mycologists, and enthusiasts alike, as it aids in distinguishing edible species from poisonous ones and provides clues about the mushroom’s ecological role.

Cap color often directly correlates with the species of the mushroom, acting as a taxonomic marker. For example, the vivid red-and-white cap of the Fly Agaric is instantly recognizable, while the golden-yellow cap of the Lion’s Mane (*Hericium erinaceus*) distinguishes it from other species. Some genera, like *Cortinarius*, exhibit a wide range of cap colors, from browns and grays to purples and blues, reflecting their diverse species within the group. These colors are influenced by pigments such as melanins, carotenoids, and anthraquinones, which are genetically determined. Thus, observing cap color is a fundamental step in narrowing down the identity of a mushroom during field identification.

The habitat of a mushroom also plays a significant role in determining cap color, as it adapts to its surroundings for survival. Mushrooms in open, sunlit areas, such as meadows, often have darker caps to protect their spores from UV radiation, as seen in the Dark-Gilled Agaric (*Agaricus brunnescens*). Conversely, mushrooms in shaded environments, like dense forests, tend to have lighter or more muted caps to maximize light absorption for photosynthesis in their symbiotic partners. Additionally, mushrooms growing on decaying wood, such as the Oyster Mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), often have caps that mimic the color of their substrate, providing camouflage from predators and environmental stressors.

Cap color is also a reliable indicator of a mushroom’s maturity stage, changing as the fungus develops. Young mushrooms often have caps that are tightly closed and may appear lighter or more uniform in color, as seen in the button stage of the Common White Mushroom (*Agaricus bisporus*). As the mushroom matures, the cap expands, and its color may darken, lighten, or develop patterns like spots or streaks. For example, the cap of the Shaggy Mane (*Coprinus comatus*) starts off white and gradually turns black as it deliquesces. These color changes are linked to spore release and the mushroom’s life cycle, making them valuable for assessing edibility and ecological function.

In summary, the color of a mushroom’s cap is far more than an aesthetic feature; it is a multifaceted indicator of species, habitat, and maturity stage. By carefully observing cap color, one can gain deeper insights into the mushroom’s identity, ecological role, and developmental phase. This knowledge is crucial for safe foraging, scientific study, and appreciating the diversity of the fungal kingdom. Whether in the field or the lab, paying attention to cap color unlocks a wealth of information about these fascinating organisms.

Mushroom Toxins: Understanding the Poisonous Components

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Texture Types: Smooth, scaly, or slimy textures help classify mushroom varieties

The top of a mushroom, known as the pileus or cap, is a critical feature for identification, and its texture plays a significant role in classifying mushroom varieties. Texture can vary widely, with smooth, scaly, or slimy surfaces being among the most common types. Understanding these textures is essential for foragers, mycologists, and enthusiasts alike, as they provide key clues to a mushroom's species and edibility. Smooth-capped mushrooms, for instance, often have a sleek, even surface that feels velvety or matte to the touch. Examples include the common button mushroom (*Agaricus bisporus*) and the chanterelle (*Cantharellus cibarius*), which are prized for their culinary uses. Smooth textures are typically associated with mushrooms that grow in open, well-drained environments, as their caps are less likely to retain debris or moisture.

In contrast, scaly textures are characterized by small, raised bumps or flakes on the cap's surface. These scales can range from fine and subtle to coarse and prominent, often resembling fish scales or cracked earth. The *Boletus edulis*, commonly known as the porcini, is a prime example of a scaly-capped mushroom. Its distinctive brown cap with white or tan scales is a hallmark of the species. Scaly textures often indicate mushrooms that grow in wooded areas, where the scales may help protect the cap from moisture or insect damage. Foragers should note that while many scaly mushrooms are edible, some toxic species, like the *Galerina marginata*, also exhibit this texture, underscoring the importance of careful identification.

Slimy or viscid textures are another important category, where the cap feels sticky or gelatinous to the touch. This texture is often caused by a mucus layer that helps the mushroom retain moisture in dry conditions. The *Mycena* genus, commonly known as bonnet mushrooms, is a classic example of slimy-capped fungi. While some slimy mushrooms, like the *Exidia glandulosa* (black witch’s butter), are inedible or unpalatable, others, such as the *Pholiota nameko*, are cultivated for culinary use in dishes like miso soup. Slimy textures can also serve as a defense mechanism, deterring insects or other predators.

Texture is not just a tactile characteristic but often correlates with a mushroom's habitat, growth stage, and ecological role. For instance, smooth caps are more common in cultivated mushrooms, while scaly and slimy textures are frequently found in wild varieties. Observing texture alongside other features like color, gills, and spore print can significantly enhance accuracy in mushroom identification. For beginners, starting with texture as a primary identifier can simplify the learning process, as it is often more immediately apparent than subtler characteristics like spore color or gill attachment.

In conclusion, the texture of a mushroom's cap—whether smooth, scaly, or slimy—is a vital tool for classification and identification. Each texture type not only helps distinguish between species but also provides insights into the mushroom's environment and potential uses. As with all foraging, caution is paramount, and relying on multiple characteristics, including texture, is essential to avoid misidentification. By mastering the nuances of cap textures, enthusiasts can deepen their appreciation of the diverse and fascinating world of fungi.

Mushroom Cells: Specialized or Not?

You may want to see also

Margin Features: Characteristics like striations or curling edges aid in identification

The top of a mushroom is called the pileus, commonly referred to as the cap. When identifying mushrooms, the margin features of the pileus play a crucial role. These characteristics, such as striations or curling edges, provide distinct clues that aid in accurate identification. Striations, for instance, are fine, radial lines or grooves that extend from the cap's center to its edge. They are often more pronounced in certain species, like the *Psathyrella* genus, and can help differentiate between similar-looking mushrooms. Observing these striations closely, including their depth, spacing, and continuity, is essential for precise identification.

Curling edges, another key margin feature, refer to the way the cap's edge (or margin) bends or rolls inward, outward, or in a wavy pattern. This characteristic varies widely among species and can be influenced by the mushroom's age, moisture levels, or genetic traits. For example, the margin of an immature *Amanita* mushroom often curls inward, while in older specimens, it may flatten or even curl outward. Noting whether the edge is smooth, jagged, or split further refines identification. These subtle details, when combined with other features, can distinguish between edible and toxic species, making margin examination a critical step in mycology.

In addition to striations and curling edges, the texture of the margin is another important feature. Some mushrooms have smooth margins, while others may exhibit fibrillose (hairy or fibrous) or scalloped edges. For instance, the margin of a *Lactarius* mushroom often feels slightly hairy, aiding in its identification. The presence of partial veils or remnants of a universal veil at the margin, as seen in *Amanita* species, is also diagnostic. These veil remnants can appear as patches, rings, or fringes along the edge, providing additional clues about the mushroom's taxonomy.

Color changes at the margin are yet another characteristic to consider. Some mushrooms, like the *Hygrocybe* genus, may have margins that are a different color from the rest of the cap, often brighter or more vibrant. Others may darken or lighten at the edges due to age, environmental factors, or spore maturity. Documenting these color variations, along with other margin features, enhances the accuracy of identification. For example, a margin that starts white but turns brown with age can be a defining trait for certain species.

Lastly, the shape and thickness of the margin are fundamental aspects of mushroom identification. A thin, sharp margin contrasts with a thick, fleshy one, and both can be indicative of specific genera or species. For instance, the margin of a *Marasmius* mushroom is typically thin and delicate, while that of a *Boletus* is often thick and rolled under. These structural differences, combined with other margin features like striations or curling edges, create a comprehensive profile for identification. By carefully examining these characteristics, enthusiasts and experts alike can confidently classify mushrooms and appreciate the diversity of the pileus margin.

Wild Mushrooms: Are They Safe or Poisonous?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The top of a mushroom is called the cap or pileus.

Yes, the cap protects the gills or pores underneath, which are responsible for spore production and reproduction.

No, mushroom caps vary widely in shape, size, color, and texture depending on the species.

Yes, the cap’s characteristics, such as color, shape, and texture, are key features used in mushroom identification.

It depends on the species. Some mushroom caps are edible and delicious, while others are toxic or poisonous, so proper identification is crucial.