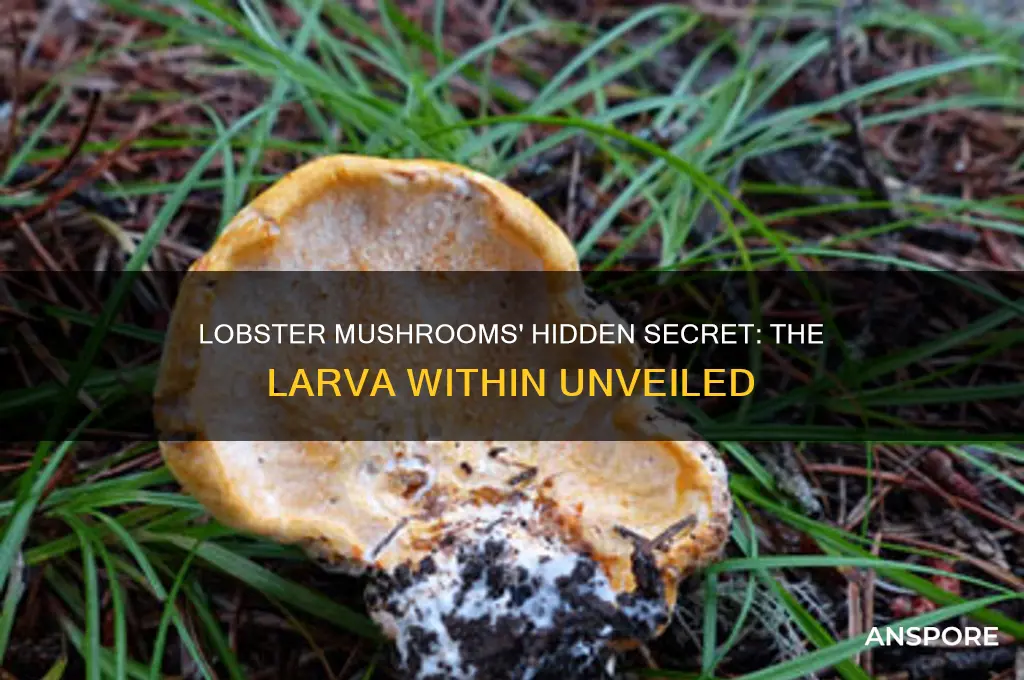

Lobster mushrooms, despite their name, are not actually mushrooms but rather a unique culinary delicacy formed through a parasitic relationship between a fungus (*Hypomyces lactifluorum*) and certain species of mushrooms, typically from the *Lactarius* or *Russula* genera. The fungus colonizes the host mushroom, transforming its appearance and texture, resulting in the lobster mushroom's distinctive orange-red color and seafood-like flavor. Interestingly, the life cycle of the *Hypomyces lactifluorum* fungus involves a larval stage, though it is not a larva in the traditional sense, as fungi do not undergo metamorphosis like insects. Instead, the fungus produces spores that germinate and grow, eventually infecting a suitable host mushroom. This symbiotic yet parasitic relationship highlights the intricate ecological interactions in fungal biology, making the lobster mushroom a fascinating subject for both mycologists and culinary enthusiasts.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Larva Species | Hypomyces lactifluorum (fungus, not a true larva) |

| Common Name | Lobster Mushroom |

| Host Mushroom | Typically Lactarius or Russula species |

| Appearance | Bright orange-red, lobster-like color; transforms host mushroom into a hard, rubbery texture |

| Habitat | Coniferous and deciduous forests, often found near trees |

| Edibility | Edible and prized for its seafood-like flavor; must be cooked |

| Life Cycle | Parasitic fungus that infects and transforms host mushrooms |

| Season | Late summer to fall |

| Geographic Range | North America, Europe, and Asia |

| Ecological Role | Parasite, alters host mushroom's structure and appearance |

| Distinct Feature | Loses toxicity of host mushroom after transformation |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Hypomyces lactifluorum fungus role

The Hypomyces lactifluorum fungus plays a pivotal role in the development and transformation of lobster mushrooms, a unique and sought-after culinary delicacy. This fungus is a parasitic ascomycete that specifically targets certain species of Lactarius mushrooms, most commonly *Lactarius piperatus* and *Lactarius rufus*, though other species can also be affected. The interaction between Hypomyces lactifluorum and its host mushroom is a complex ecological relationship that results in the distinctive appearance and texture of the lobster mushroom. When the fungus infects the host, it envelops the mushroom, altering its structure and giving it a lobster-like color and firm, chewy texture. This transformation is not merely superficial; it involves the fungus breaking down the host’s tissues and replacing them with its own mycelium, effectively hijacking the mushroom’s resources.

One of the most fascinating aspects of Hypomyces lactifluorum’s role is its ability to enhance the edibility of the host mushroom. The Lactarius species it parasitizes are often unpalatable due to their acrid latex, which contains compounds that can cause gastrointestinal discomfort. However, when Hypomyces lactifluorum colonizes these mushrooms, it neutralizes these compounds, rendering the mushroom safe and even desirable to eat. This process not only benefits humans but also other organisms in the ecosystem, as the transformed mushroom becomes a more accessible food source. The fungus, in turn, gains nutrients and a means of dispersal, as the mushroom’s structure aids in spore distribution.

The life cycle of Hypomyces lactifluorum is closely tied to its parasitic nature. The fungus produces spores that are released into the environment, and when conditions are favorable, these spores germinate and infect susceptible Lactarius mushrooms. Once infection occurs, the fungus grows rapidly, covering the host in a thick, orange-red layer that resembles the shell of a lobster. This growth phase is critical, as it determines the quality and appearance of the final lobster mushroom. The fungus’s role here is not just destructive but also constructive, as it reshapes the host into a new form that is both ecologically and culinarily significant.

From an ecological perspective, Hypomyces lactifluorum serves as a key player in nutrient cycling within forest ecosystems. By parasitizing and transforming Lactarius mushrooms, it accelerates the decomposition process, breaking down complex organic matter into simpler forms that can be reused by other organisms. This function is particularly important in nutrient-poor environments, where efficient recycling of organic material is essential for maintaining ecosystem health. Additionally, the presence of lobster mushrooms can indicate a healthy, diverse fungal community, as they are the product of a specific and intricate ecological interaction.

For foragers and chefs, understanding the role of Hypomyces lactifluorum is crucial for identifying and harvesting lobster mushrooms safely. The fungus’s transformation of the host mushroom not only changes its appearance but also its culinary properties. Lobster mushrooms are prized for their seafood-like flavor and meaty texture, making them a versatile ingredient in various dishes. However, proper identification is essential, as not all orange-red mushrooms are lobster mushrooms, and some can be toxic. By recognizing the specific characteristics imparted by Hypomyces lactifluorum, such as the firm texture and lack of latex, foragers can confidently distinguish lobster mushrooms from their look-alikes.

In summary, Hypomyces lactifluorum plays a multifaceted role in the creation of lobster mushrooms, acting as both a parasite and a transformer. Its ability to neutralize the host’s toxins, alter its structure, and enhance its edibility highlights the intricate relationships within fungal ecosystems. Beyond its ecological significance, the fungus’s role has practical implications for foraging and culinary arts, making it a fascinating subject of study for mycologists, ecologists, and food enthusiasts alike.

Discovering Morel Mushrooms: Do They Thrive in Kansas' Forests?

You may want to see also

Host mushroom species identification

The lobster mushroom, despite its name, is not a single species but rather a unique culinary and ecological phenomenon resulting from a parasitic relationship. It is primarily the fruiting body of the mushroom *Hypomyces lactifluorum*, which parasitizes certain host mushrooms, most commonly species from the genus *Lactarius* and occasionally *Russula*. Identifying the host mushroom species within a lobster mushroom is crucial for understanding its biology, distribution, and potential culinary uses. The process involves careful examination of the parasitized mushroom's residual characteristics, as the *Hypomyces* parasite significantly alters the host's appearance.

To identify the host mushroom species, begin by observing the overall structure and remnants of the original mushroom beneath the lobster mushroom's orange-red, shaggy crust. The host typically belongs to the *Lactarius* genus, known as milk-caps, which are characterized by their latex-like substance exuded when injured. Look for remnants of the host's cap and stem structure, which may still retain some of the original shape or color beneath the parasitic growth. The presence of latex, even in trace amounts, is a strong indicator of a *Lactarius* host. If latex is absent, consider the possibility of a *Russula* host, which lacks latex but shares similar gill and spore characteristics.

Microscopic examination is another valuable tool for host identification. Carefully extract a small tissue sample from the interior of the lobster mushroom, where the host's hyphae may still be intact. Prepare a spore print or mount a gill sample on a slide to observe spore morphology under a microscope. *Lactarius* spores are typically ellipsoid or spherical with distinct ornamentation, while *Russula* spores are often more elongated and amyloid. Comparing these features to known spore characteristics of *Lactarius* and *Russula* species can help narrow down the host identity.

Environmental and geographical factors also play a role in host species identification. *Lactarius* and *Russula* species have specific habitat preferences, such as coniferous or deciduous forests, which can provide clues about the likely host. For example, *Lactarius piperatus* and *Lactarius rufus* are commonly parasitized by *Hypomyces lactifluorum* in North America and Europe, respectively. Consulting regional mycological guides or databases can aid in matching the lobster mushroom's location to potential host species.

Finally, molecular techniques, such as DNA sequencing, offer a definitive method for identifying the host mushroom species. Extracting DNA from the lobster mushroom and amplifying specific gene regions, such as the ITS (Internal Transcribed Spacer) region, allows for comparison with known sequences in fungal databases. This approach is particularly useful when morphological characteristics are ambiguous or insufficient for identification. Combining morphological, microscopic, and molecular methods ensures accurate and comprehensive host species identification in lobster mushrooms.

Can Mushrooms Grow on Feet? Uncovering the Truth Behind the Myth

You may want to see also

Larva life cycle stages

The larva that grows in lobster mushrooms is the Hypomyces lactifluorum, a parasitic ascomycete fungus. However, it’s important to clarify that lobster mushrooms themselves are not larvae but rather a unique culinary mushroom formed when *Hypomyces lactifluorum* infects a species of milk-cap mushroom (*Lactarius* or *Lactarius piperatus*). While *Hypomyces lactifluorum* is a fungus, not a larva, the confusion may arise from the mushroom’s appearance or the presence of insect larvae in similar environments. For the purpose of this explanation, I will focus on the life cycle stages of a common larva that might be found in or around lobster mushrooms, such as the fly larva (e.g., *Drosophila* or other fungi-associated larvae), which could mistakenly be associated with lobster mushrooms.

Egg Stage: The larva life cycle begins with the egg stage. Female flies lay their eggs on or near decaying organic matter, including fungi-rich environments where lobster mushrooms might grow. These eggs are typically tiny, oval-shaped, and laid in clusters. The eggs hatch within 24 to 48 hours, depending on temperature and humidity, giving rise to the larval stage.

Larval Stage: Once hatched, the larvae emerge as small, worm-like creatures with a voracious appetite. This stage is the most active feeding period, where larvae consume fungi, decaying plant material, or other organic matter. The larvae grow rapidly, molting several times as they increase in size. This stage lasts approximately 4 to 7 days, during which the larvae prepare for the next phase of their life cycle.

Pupal Stage: After reaching full size, the larvae seek a safe location to pupate. They enclose themselves in a protective casing, often within the soil or substrate, and undergo a transformative process called metamorphosis. During this stage, the larval body breaks down and reorganizes into the adult form. The pupal stage typically lasts 3 to 10 days, depending on environmental conditions.

Adult Stage: Upon completing metamorphosis, the adult fly emerges from the pupal case. The primary goal of the adult stage is reproduction. Adult flies feed on sugars from fruits, nectar, or other sources to gain energy for mating and egg-laying. The lifespan of an adult fly is relatively short, usually lasting only a few days to a couple of weeks, after which the cycle begins anew with the laying of eggs.

While the larvae discussed here are not directly associated with lobster mushrooms, their presence in similar habitats highlights the interconnectedness of fungi, insects, and their life cycles in forest ecosystems. Understanding these stages provides insight into the broader ecological dynamics of mushroom-rich environments.

Exploring Morel Mushrooms: Do They Thrive in Costa Rica's Climate?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Impact on mushroom flavor/texture

The presence of larvae in lobster mushrooms, specifically those of the fly species *Phytomyza hypophyllae*, significantly impacts both the flavor and texture of the mushroom. These larvae feed on the mushroom’s tissues, altering its structural integrity and chemical composition. As the larvae consume the mushroom’s flesh, they create tunnels and cavities, which disrupt the mushroom’s dense, meaty texture. This results in a softer, almost spongy consistency in the affected areas, making the mushroom less firm and more fragile when handled or cooked. The texture change is particularly noticeable in mature mushrooms with advanced larval infestations, where the once-chewy flesh becomes uneven and pockmarked.

In terms of flavor, the larvae’s activity introduces a unique set of enzymes and metabolic byproducts into the mushroom. These compounds can subtly alter the mushroom’s natural earthy and seafood-like taste, often associated with its "lobster" moniker. Some foragers and chefs note that infested lobster mushrooms may develop a slightly sweeter or nuttier undertone, likely due to the breakdown of complex carbohydrates and proteins by the larvae. However, this flavor enhancement is subjective and depends on the extent of the infestation. Overly infested mushrooms may instead take on a milder, less pronounced taste, as the larvae’s activity dilutes the mushroom’s natural flavor compounds.

The impact on texture and flavor also varies depending on the stage of larval development. Younger larvae cause minimal damage, preserving much of the mushroom’s original texture and taste. As the larvae mature and increase in size, their feeding becomes more aggressive, leading to greater textural degradation and flavor modification. For culinary purposes, foragers often prefer lightly infested mushrooms, as they retain a desirable balance of texture and enhanced flavor without becoming too soft or bland.

Cooking methods can mitigate some of the textural changes caused by larval activity. Sautéing or grilling infested lobster mushrooms can help firm up the softer areas, restoring some of the mushroom’s original chewiness. However, the flavor alterations are more permanent and can be accentuated by heat, making the sweeter or nuttier notes more pronounced. This duality—texture that can be partially rescued but flavor that is irreversibly changed—makes larval-infested lobster mushrooms a unique ingredient that requires careful handling and preparation.

Ultimately, the larvae’s impact on lobster mushroom flavor and texture is a double-edged sword. While they introduce intriguing flavor nuances and soften the mushroom’s texture, they also reduce the overall quality if the infestation is severe. Foragers and chefs must carefully inspect lobster mushrooms for larval activity, selecting specimens with minimal infestation to strike the right balance between the mushroom’s natural characteristics and the subtle changes brought about by the larvae. This ensures that the mushroom’s culinary potential is maximized without compromising its structural integrity or flavor profile.

Easy Guide to Growing Mushrooms at Home in Kenya

You may want to see also

Ecological significance of infestation

The lobster mushroom, *Hypomyces lactifluorum*, is a unique fungal species that parasitizes other mushrooms, particularly those in the *Lactarius* and *Russula* genera. Within this parasitic relationship, the larva of a specific fly species, *Philomyces lactifluorum*, plays a crucial role. This larva infests the lobster mushroom, contributing to its distinctive appearance and ecological interactions. Understanding the ecological significance of this infestation requires examining the broader impacts on forest ecosystems, nutrient cycling, and interspecies relationships.

From an ecological perspective, the infestation of lobster mushrooms by *Philomyces lactifluorum* larvae enhances nutrient cycling in forest ecosystems. As the larvae consume the mushroom tissue, they break down complex organic matter into simpler forms. This process accelerates decomposition, releasing nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus back into the soil. These nutrients are then available for uptake by plants and other fungi, fostering healthier forest floors and supporting the growth of diverse vegetation. Thus, the larvae act as micro-decomposers, playing a vital role in maintaining soil fertility and ecosystem productivity.

The infestation also influences predator-prey dynamics within the forest. The larvae serve as a food source for various invertebrates, small mammals, and birds, which are attracted to the lobster mushroom's vibrant color and odor. This interaction creates a localized food web, where the presence of infested mushrooms supports higher trophic levels. For example, insects and rodents that feed on the larvae become prey for larger predators, demonstrating how the infestation contributes to energy flow and biodiversity within the ecosystem.

Furthermore, the infestation of lobster mushrooms by these larvae highlights the intricate coevolutionary relationships between fungi, insects, and their environment. The larvae's ability to thrive within the mushroom suggests a specialized adaptation to this habitat, while the mushroom's parasitic nature on other fungi adds another layer of complexity. Such relationships underscore the interconnectedness of species in ecosystems and the importance of preserving these interactions for ecological stability. Disruptions to these relationships, such as through habitat loss or climate change, could have cascading effects on forest health.

Lastly, the infestation has implications for human interactions with forest ecosystems, particularly in the context of foraging and conservation. Lobster mushrooms are prized by foragers for their culinary value, but the presence of larvae often renders them unappealing or unsuitable for consumption. This natural process acts as a regulatory mechanism, limiting overharvesting and ensuring the sustainability of mushroom populations. Additionally, studying this infestation provides insights into fungal ecology and pest management, which can inform conservation strategies to protect vulnerable forest ecosystems.

In summary, the infestation of lobster mushrooms by *Philomyces lactifluorum* larvae holds significant ecological importance. It enhances nutrient cycling, supports predator-prey dynamics, exemplifies coevolutionary relationships, and influences human interactions with forests. By examining this infestation, we gain a deeper understanding of the intricate web of life in forest ecosystems and the need to preserve these delicate interactions for long-term ecological health.

Do Shiitake Mushrooms Grow on Trees? Unveiling the Truth

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The larva of the *Hypomyces lactifluorum* fungus grows in lobster mushrooms, transforming the host mushroom into the lobster-like appearance.

Yes, lobster mushrooms are safe to eat even with the *Hypomyces lactifluorum* fungus present, as it is not harmful to humans.

The larva-like growth of *Hypomyces lactifluorum* turns the host mushroom a reddish-orange color, giving it a lobster-like appearance and texture.

No, the *Hypomyces lactifluorum* fungus does not cause illness in humans and is considered edible when properly prepared.

The larva-like fungus *Hypomyces lactifluorum* typically infects species of the *Lactarius* or *Russula* genus to form lobster mushrooms.