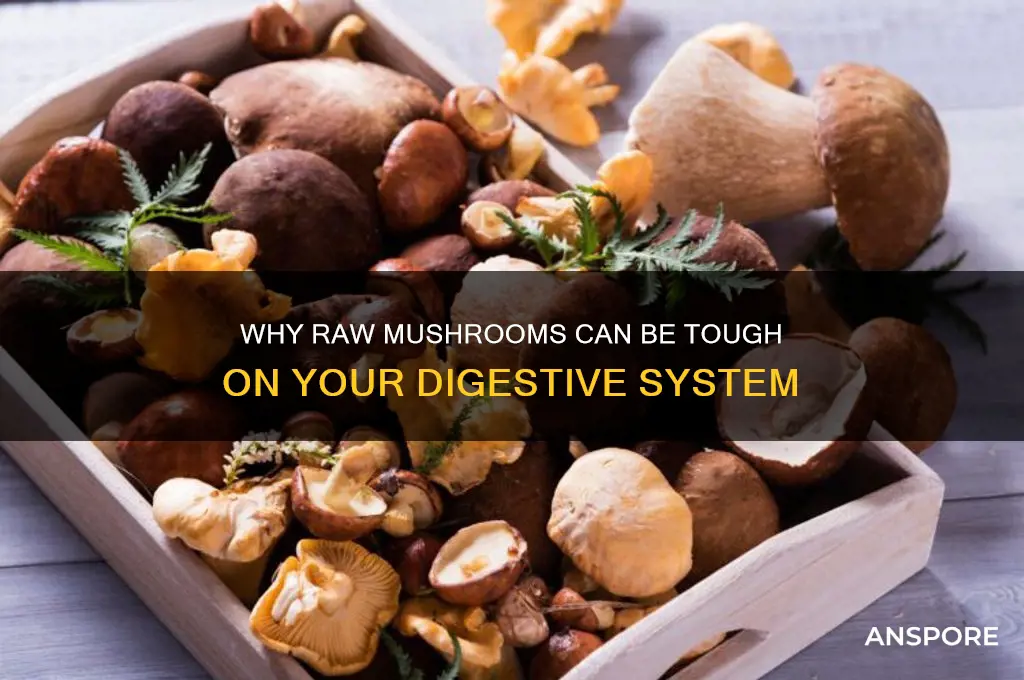

Raw mushrooms can be difficult to digest due to their tough cell walls, which are composed of chitin, a complex carbohydrate that the human digestive system lacks the enzymes to break down efficiently. Additionally, raw mushrooms contain certain proteins and toxins that can irritate the gastrointestinal tract, potentially leading to discomfort, bloating, or even allergic reactions in some individuals. Cooking mushrooms helps to break down these cell walls, making them easier to digest and reducing the risk of adverse effects, while also enhancing their nutritional availability and flavor.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Chitin Content | Mushrooms contain chitin, a complex carbohydrate found in their cell walls. Chitin is difficult for the human digestive system to break down, leading to reduced nutrient absorption and potential digestive discomfort. |

| Tough Cell Walls | The cell walls of raw mushrooms are tough and fibrous, making them harder to chew and digest compared to cooked mushrooms. |

| Enzyme Inhibitors | Raw mushrooms contain enzyme inhibitors that can interfere with the digestion of proteins and carbohydrates, potentially causing bloating and gas. |

| Hard-to-Digest Proteins | Mushrooms contain proteins that are resistant to digestion in their raw state, which can lead to digestive issues for some individuals. |

| Potential Toxins | Some raw mushroom varieties contain mild toxins or irritants that can cause gastrointestinal distress when consumed uncooked. Cooking typically neutralizes these substances. |

| High Fiber Content | While fiber is generally beneficial, the high fiber content in raw mushrooms can be difficult for some people to digest, leading to bloating and discomfort. |

| Lack of Heat Breakdown | Cooking mushrooms breaks down their complex structures, making nutrients more accessible and easier to digest. Raw mushrooms lack this benefit. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Tough Cell Walls: Chitin in mushroom cell walls resists human digestive enzymes, slowing breakdown

- Lactarius Syndrome: Certain raw mushrooms cause gastrointestinal irritation due to toxins like lactarorufin

- Hard-to-Absorb Nutrients: Raw mushrooms lock nutrients like beta-glucans, reducing bioavailability

- Potential Allergens: Raw mushrooms may trigger allergic reactions in sensitive individuals, causing digestive issues

- Anti-Nutritional Factors: Raw mushrooms contain compounds like agaritine, which can irritate the gut

Tough Cell Walls: Chitin in mushroom cell walls resists human digestive enzymes, slowing breakdown

Mushrooms, unlike most vegetables, are not plants but fungi, and this distinction is key to understanding why their raw form can be a digestive challenge. The culprit lies in their cell walls, which are fortified with a substance called chitin. This complex carbohydrate is also found in the exoskeletons of insects and crustaceans, and it’s remarkably resistant to the digestive enzymes produced by the human body. When you consume raw mushrooms, your stomach and intestines struggle to break down this chitinous barrier, leaving much of the mushroom’s nutrients locked away and unabsorbed.

To illustrate, imagine trying to chew through a piece of cardboard. Your teeth might make some progress, but it’s slow and inefficient. Similarly, human digestive enzymes like amylase, protease, and lipase are ineffective against chitin. The body lacks chitinase, the enzyme needed to degrade chitin, which is why raw mushrooms often pass through the digestive tract largely intact. This inefficiency can lead to discomfort, bloating, or even mild gastrointestinal distress, particularly in individuals with sensitive digestive systems.

Cooking mushrooms, however, is a game-changer. Heat breaks down chitin, softening the cell walls and making the mushrooms easier to digest. Studies show that cooking mushrooms at temperatures above 140°F (60°C) for at least 5–10 minutes significantly reduces chitin content, allowing digestive enzymes to access and process the nutrients inside. For example, a 2015 study published in the *International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition* found that cooked mushrooms had a 50–70% higher bioavailability of nutrients like protein, fiber, and antioxidants compared to their raw counterparts.

If you’re determined to eat mushrooms raw, moderation is key. Start with small portions—no more than 50 grams (about 1/4 cup sliced) per day—to minimize digestive strain. Pairing raw mushrooms with foods high in natural enzymes, such as pineapple (rich in bromelain) or papaya (rich in papain), may also aid digestion. However, for most people, cooking remains the most practical solution. Sautéing, grilling, or steaming not only enhances digestibility but also unlocks the full nutritional potential of mushrooms, making them a more valuable addition to your diet.

In conclusion, chitin in mushroom cell walls is the primary reason raw mushrooms are hard to digest. While cooking is the simplest remedy, understanding this biological barrier empowers you to make informed choices. Whether you’re a culinary enthusiast or a health-conscious eater, knowing how to prepare mushrooms properly ensures you reap their benefits without the discomfort.

Mastering Mushroom Brew: Simple Steps for a Nutritious, Earthy Elixir

You may want to see also

Lactarius Syndrome: Certain raw mushrooms cause gastrointestinal irritation due to toxins like lactarorufin

Raw mushrooms, particularly those from the *Lactarius* genus, can trigger a unique and unpleasant reaction known as Lactarius Syndrome when consumed raw. This condition is not merely a result of indigestion but is specifically tied to toxins like lactarorufin, which are present in these mushrooms. Unlike general digestive discomfort, Lactarius Syndrome manifests as acute gastrointestinal irritation, including symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. These toxins are heat-labile, meaning they break down when exposed to high temperatures, which is why cooking these mushrooms renders them safe to eat. However, in their raw state, they retain their toxic properties, making them a potential hazard for foragers and culinary enthusiasts alike.

To understand the mechanism behind Lactarius Syndrome, consider how lactarorufin interacts with the digestive system. When ingested raw, this toxin irritates the mucous membranes of the gastrointestinal tract, leading to inflammation and discomfort. The severity of symptoms can vary depending on the amount consumed and individual sensitivity. For instance, a small bite of a raw *Lactarius* mushroom might cause mild nausea, while consuming a larger quantity could result in severe gastrointestinal distress. This reaction is not an allergic response but a direct result of the toxin’s presence, making it predictable and avoidable with proper preparation.

Foraging for wild mushrooms is a popular activity, but it comes with risks, especially when it involves *Lactarius* species. Identifying these mushrooms correctly is crucial, as they often resemble edible varieties. A practical tip for foragers is to always cook any harvested *Lactarius* mushrooms thoroughly before tasting. Boiling or sautéing them for at least 10 minutes ensures that toxins like lactarorufin are neutralized. Additionally, avoiding raw consumption altogether is the safest approach, particularly for children and individuals with sensitive digestive systems, as they may be more susceptible to severe reactions.

Comparing Lactarius Syndrome to other mushroom-related ailments highlights its unique nature. Unlike amatoxin poisoning from *Amanita* species, which can be life-threatening, Lactarius Syndrome is typically self-limiting and resolves within 24 hours without medical intervention. However, its onset is rapid, often occurring within 30 minutes to 2 hours after ingestion, making it a memorable and unpleasant experience. This contrasts with other mushroom toxins that may take hours or even days to cause symptoms. Understanding these differences underscores the importance of proper mushroom preparation and the specific risks associated with raw *Lactarius* mushrooms.

In conclusion, Lactarius Syndrome serves as a cautionary tale for mushroom enthusiasts. While *Lactarius* mushrooms can be a delicious addition to meals when cooked, their raw form harbors toxins that cause significant gastrointestinal irritation. By recognizing the risks, practicing safe foraging techniques, and always cooking these mushrooms, individuals can enjoy their culinary benefits without the discomfort of Lactarius Syndrome. This knowledge not only enhances safety but also deepens appreciation for the complexities of the natural world and its edible treasures.

Delicious Oyster Mushroom Siomai: A Step-by-Step Recipe Guide

You may want to see also

Hard-to-Absorb Nutrients: Raw mushrooms lock nutrients like beta-glucans, reducing bioavailability

Raw mushrooms, while nutrient-dense, present a paradox: their cell walls are fortified with chitin, a fibrous compound also found in insect exoskeletons and shellfish. This chitinous barrier is indigestible to humans, effectively locking in key nutrients like beta-glucans, polysaccharides renowned for immune-modulating properties. Studies show that raw mushrooms retain up to 90% of their beta-glucans, yet the human gut lacks the enzymes to break down chitin, rendering much of this nutrient inaccessible. This structural inaccessibility reduces bioavailability, meaning your body absorbs only a fraction of the potential benefits.

Consider beta-glucans, which require extraction from the chitin matrix for absorption. Research indicates that cooking mushrooms at temperatures above 140°F (60°C) breaks down chitin, increasing beta-glucan bioavailability by up to 60%. For instance, a 100g serving of raw shiitake mushrooms contains approximately 500mg of beta-glucans, but only 200mg may be absorbed raw. Lightly sautéing or steaming the same portion can unlock closer to 300mg, tripling the effective dosage. This simple culinary step transforms mushrooms from a nutrient-rich but inefficient food into a potent immune-boosting ally.

The implications extend beyond beta-glucans. Raw mushrooms also contain ergothioneine, an antioxidant trapped within the chitinous cell walls. A 2021 study in *Food Chemistry* found that ergothioneine levels in raw mushrooms were 40% less bioavailable compared to cooked varieties. For individuals over 50, whose digestive efficiency declines, this difference is critical. Incorporating cooked mushrooms into meals—such as grilled portobellos or simmered cremini—ensures maximal nutrient extraction, particularly for age groups needing heightened antioxidant support.

Practical application is key. To optimize nutrient absorption, avoid high-heat methods like deep-frying, which can degrade heat-sensitive compounds. Instead, opt for gentle cooking techniques: simmer mushrooms in soups for 15–20 minutes, or roast them at 350°F (175°C) for 20–25 minutes. Pairing cooked mushrooms with vitamin C-rich foods, such as bell peppers or citrus, further enhances beta-glucan absorption by up to 20%. For those incorporating mushrooms into raw diets, blending or fermenting them can partially break down chitin, though cooking remains the most effective method.

In summary, raw mushrooms’ chitin-rich cell walls act as a nutrient vault, limiting access to beta-glucans and other bioactives. Cooking is not merely a culinary preference but a biological necessity for unlocking these compounds. By applying heat strategically and combining mushrooms with complementary foods, individuals can transform this hard-to-digest fungus into a powerhouse of absorbable nutrients, bridging the gap between potential and practicality.

Creamy Mushroom Sauce Recipe: Elevate Your Pork Chops with Ease

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Potential Allergens: Raw mushrooms may trigger allergic reactions in sensitive individuals, causing digestive issues

Raw mushrooms, while nutrient-rich, can be a hidden minefield for individuals with specific sensitivities. Among the lesser-known culprits behind digestive discomfort are mushroom allergens, which can provoke reactions ranging from mild to severe. Unlike common allergens like peanuts or shellfish, mushroom allergies often fly under the radar, making them a potential blind spot for those exploring plant-based diets or culinary experimentation. Understanding this risk is crucial, as allergic reactions can manifest as gastrointestinal distress, including bloating, cramps, and diarrhea, often mistaken for general indigestion.

For sensitive individuals, the proteins in raw mushrooms act as triggers, prompting the immune system to overreact. This response can be immediate or delayed, complicating diagnosis. Symptoms may include itching, swelling, or hives, but digestive issues are particularly common due to the direct interaction between mushroom proteins and the gut lining. Notably, cooking mushrooms typically denatures these proteins, reducing allergenic potential, which underscores why raw consumption poses a higher risk. If you suspect a mushroom allergy, start by eliminating raw mushrooms from your diet and consult an allergist for testing, such as skin prick tests or blood assays, to confirm the diagnosis.

Children and adults alike can develop mushroom allergies, though onset often occurs after repeated exposure. For parents introducing mushrooms to a child’s diet, begin with small, cooked portions to monitor tolerance. Adults experimenting with raw mushroom recipes, such as salads or smoothies, should proceed cautiously, especially if they have a history of food allergies or sensitivities. Keeping an antihistamine on hand is a practical precaution, but it’s not a substitute for avoiding the allergen altogether. Awareness and proactive management are key to preventing discomfort and potential health risks.

To mitigate risks, consider alternatives like thoroughly cooked mushrooms or mushroom extracts, which are less likely to provoke reactions. If raw mushrooms are a dietary staple, maintain a food diary to track symptoms and identify patterns. For those confirmed to have a mushroom allergy, cross-reactivity with other fungi, such as mold or yeast, may also be a concern, so broader dietary adjustments might be necessary. Ultimately, while raw mushrooms offer health benefits, they are not universally benign, and prioritizing digestive well-being requires informed, individualized choices.

Craft Adorable Marshmallow Mushroom Pops: A Fun DIY Treat Idea

You may want to see also

Anti-Nutritional Factors: Raw mushrooms contain compounds like agaritine, which can irritate the gut

Raw mushrooms, while nutrient-dense, harbor compounds that challenge digestion, particularly when consumed uncooked. Among these, agaritine stands out as a key anti-nutritional factor. This hydrazine derivative, found in varying concentrations across mushroom species, can irritate the gastrointestinal tract, leading to discomfort such as bloating, gas, or diarrhea. For instance, *Agaricus bisporus*, the common button mushroom, contains approximately 0.1–0.2 mg of agaritine per kilogram of fresh weight. While cooking significantly reduces agaritine levels—up to 90% in some studies—raw consumption leaves this compound largely intact, amplifying its potential to disrupt gut health.

The mechanism behind agaritine’s irritant effect lies in its metabolic breakdown. When ingested, agaritine converts into arachidic acid and urea derivatives, which can damage gut epithelial cells and provoke inflammation. Individuals with pre-existing gastrointestinal conditions, such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), may experience exacerbated symptoms. Even healthy adults, when consuming raw mushrooms in moderate to high quantities (e.g., 100–200 grams daily), report transient digestive issues. For children and the elderly, whose digestive systems are more sensitive, the threshold for discomfort may be lower, making raw mushroom consumption riskier.

To mitigate these effects, practical steps can be taken. First, always cook mushrooms thoroughly, as heat degrades agaritine and other anti-nutritional compounds. Boiling, sautéing, or grilling for at least 10–15 minutes reduces agaritine levels to negligible amounts. Second, opt for younger, smaller mushrooms, which tend to have lower agaritine concentrations compared to mature specimens. Third, pair mushrooms with gut-soothing ingredients like garlic, ginger, or fermented foods to enhance digestibility. For those experimenting with raw mushrooms in smoothies or salads, start with minimal quantities (e.g., 20–30 grams) and monitor tolerance before increasing intake.

Comparatively, agaritine is not unique to mushrooms; other plant foods contain anti-nutritional factors, such as lectins in beans or oxalates in spinach. However, mushrooms’ agaritine is particularly heat-sensitive, making cooking a straightforward solution. Unlike lectins, which require soaking and prolonged cooking, agaritine’s degradation is rapid and efficient. This distinction underscores the importance of preparation methods in unlocking mushrooms’ nutritional benefits while minimizing risks. By understanding and addressing agaritine’s role, consumers can enjoy mushrooms safely, whether in a stir-fry or a soup, without compromising gut health.

Crafting the Perfect Mushroom Biome: A Guide to Growing Truffles

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Raw mushrooms contain chitin, a tough fiber in their cell walls that humans cannot fully break down, making them harder to digest.

Yes, raw mushrooms can cause bloating, gas, or stomach upset in some people due to their indigestible chitin and complex carbohydrates.

Generally, all raw mushrooms are hard to digest due to chitin, but thinner varieties like button mushrooms may cause less discomfort than denser types like portobello.

Small amounts may reduce discomfort, but raw mushrooms are still harder to digest than cooked ones, which break down chitin and release nutrients more easily.