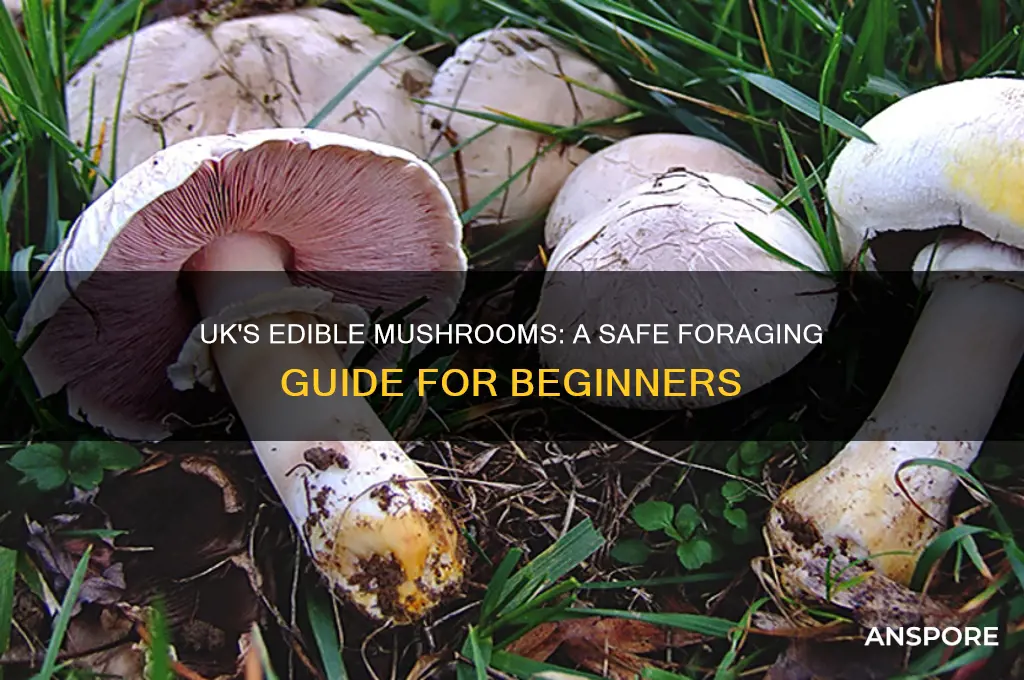

When foraging for mushrooms in the UK, it’s crucial to know which species are safe to eat, as many look similar to their toxic counterparts. Common edible mushrooms include the Field Mushroom (*Agaricus campestris*), which resembles the supermarket button mushroom, and the Chanterelle (*Cantharellus cibarius*), known for its fruity aroma and golden color. The Hedgehog Mushroom (*Hydnum repandum*) is another safe option, identifiable by its spiky underside. However, always exercise caution and consult a reliable guide or expert, as misidentification can lead to severe poisoning. Popular toxic species like the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) and the Fly Agaric (*Amanita muscaria*) highlight the importance of accurate identification before consuming any wild mushrooms.

Explore related products

$19.97 $22.97

What You'll Learn

- Common Edible Mushrooms: Identify popular, safe-to-eat mushrooms like Chanterelles, Oyster, and Cep

- Toxic Look-Alikes: Beware of poisonous doubles, such as False Chanterelles and Deadly Webcap

- Foraging Guidelines: Follow expert advice, use reliable guides, and avoid risky self-identification

- Seasonal Availability: Know when safe mushrooms grow, e.g., autumn for Ceps and Oysters

- Preparation Tips: Properly clean, cook, and store edible mushrooms to ensure safety

Common Edible Mushrooms: Identify popular, safe-to-eat mushrooms like Chanterelles, Oyster, and Cep

When foraging for mushrooms in the UK, it's essential to accurately identify species that are safe to eat. Among the most popular and easily recognizable edible mushrooms are Chanterelles, Oyster mushrooms, and Ceps (Porcini). These mushrooms are not only delicious but also widely available in British woodlands and markets. However, always ensure you are 100% certain of your identification before consuming any wild mushroom.

Chanterelles (Cantharellus cibarius) are a forager’s favorite, known for their golden-yellow color and forked, wavy caps. They have a fruity aroma, often described as apricot-like, and a chewy texture when cooked. Chanterelles grow in deciduous and coniferous forests, particularly under beech and oak trees. To identify them, look for their smooth undersides with gill-like ridges that fork and run down the stem. Avoid confusing them with the toxic False Chanterelle, which has true gills and a more muted color.

Oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) are another safe and common edible species, easily found on dead or dying hardwood trees. Named for their oyster shell-like shape, they have a grayish-brown to bluish-gray cap and a short, stubby stem. Oysters have a mild, anise-like flavor and a tender texture, making them versatile in cooking. They grow in clusters, often in large groups, and are particularly abundant in the autumn. Ensure you avoid the toxic Funeral Bell mushroom, which has a similar habitat but a darker color and a more slender stem.

Ceps or Porcini (Boletus edulis) are highly prized in the culinary world for their rich, nutty flavor and meaty texture. These mushrooms have a brown, umbrella-like cap and a thick, bulbous stem. The underside of the cap features a sponge-like pore surface rather than gills. Ceps are found in coniferous and deciduous forests, often near oak, birch, and pine trees. When foraging for Ceps, be cautious of the Devil’s Bolete, a toxic lookalike with a reddish pore surface and a bluer stem.

In the UK, these three mushrooms—Chanterelles, Oysters, and Ceps—are among the most reliable and rewarding to forage. Always cross-reference your findings with a detailed field guide or consult an expert if you’re unsure. Proper identification is key to safely enjoying the bounty of edible mushrooms available in British woodlands.

How Saprotrophic Fungi Decompose Dead Trees: Nature's Silent Recyclers

You may want to see also

Toxic Look-Alikes: Beware of poisonous doubles, such as False Chanterelles and Deadly Webcap

When foraging for mushrooms in the UK, it’s crucial to be aware of toxic look-alikes that closely resemble edible species. One notorious example is the False Chanterelle (*Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca*), which mimics the prized Golden Chanterelle (*Cantharellus cibarius*). While the Golden Chanterelle has a fruity aroma and forked gills that run down its stem, the False Chanterelle has true gills and a more acrid smell. Consuming the False Chanterelle can cause gastrointestinal distress, including nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Always inspect the gills and smell the mushroom to distinguish between these two.

Another dangerous doppelgänger is the Deadly Webcap (*Cortinarius rubellus* and *Cortinarius speciosissimus*), which can be mistaken for the edible Bay Bolete (*Boletus badius*) or other bolete species. The Deadly Webcap has a similar brown cap and stout stem but lacks the porous underside of boletes, instead having gills. It contains the toxin orellanine, which can cause severe kidney damage and even failure if ingested. To avoid confusion, always check for pores versus gills and be wary of any mushroom with a web-like partial veil under the cap, a hallmark of many *Cortinarius* species.

The Fool’s Funnel (*Clitocybe rivulosa*) is another toxic look-alike, often confused with the edible Miller (*Clitopilus prunulus*). Both have pale caps and grow in grassy areas, but the Fool’s Funnel has a more slender stem and lacks the distinctive mealy smell of the Miller. The Fool’s Funnel contains muscarine toxins, which can cause symptoms like excessive salivation, sweating, and blurred vision. Always perform a smell test and examine the stem closely to avoid this dangerous imposter.

Foragers must also beware of the Panther Cap (*Amanita pantherina*), which resembles the edible Blusher (*Amanita rubescens*). The Panther Cap has a brown cap with white flecks and a bulbous base, similar to the Blusher, but it contains psychoactive toxins that can cause hallucinations and severe gastrointestinal issues. The Blusher, when cut, turns pinkish-red, a feature the Panther Cap lacks. Always look for this color change and avoid any *Amanita* species unless you are absolutely certain of their identity.

Lastly, the Funeral Bell (*Galerina marginata*) is a deadly look-alike often mistaken for edible species like the Honey Fungus (*Armillaria mellea*). Both grow on wood, but the Funeral Bell has a smaller cap and a more slender stem. It contains amatoxins, the same toxins found in the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*), which can cause liver and kidney failure. Always inspect the habitat and spore color (the Funeral Bell has rusty-brown spores) to avoid this lethal mistake.

In summary, toxic look-alikes like the False Chanterelle, Deadly Webcap, Fool’s Funnel, Panther Cap, and Funeral Bell highlight the importance of meticulous identification. Always cross-reference multiple features—such as gills, pores, smell, habitat, and spore color—and consult a reliable field guide or expert when in doubt. Mistaking a poisonous double for an edible mushroom can have severe, even fatal, consequences.

Do Opossums Eat Mushrooms? Exploring Their Diet and Habits

You may want to see also

Foraging Guidelines: Follow expert advice, use reliable guides, and avoid risky self-identification

When foraging for mushrooms in the UK, it’s crucial to follow expert advice to ensure safety. Many mushrooms look similar, and misidentification can lead to serious illness or even death. Start by consulting mycologists (fungal experts) or joining local foraging groups led by experienced guides. These experts can provide hands-on training and help you distinguish between edible species like the Field Mushroom (*Agaricus campestris*), Chanterelles (*Cantharellus cibarius*), and Ceps (*Boletus edulis*) from toxic lookalikes such as the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) or Destroying Angel (*Amanita virosa*). Their knowledge is invaluable and can prevent dangerous mistakes.

In addition to expert guidance, use reliable guides—both in print and digital formats. Reputable field guides, such as those by authors like Roger Phillips or Patrick Harding, offer detailed descriptions, photographs, and identification keys. Apps like *Mushroom ID* or *Picture Mushroom* can also be useful, but always cross-reference findings with multiple sources. Avoid relying solely on online images or unverified information, as these can be misleading. A good rule of thumb is to only collect mushrooms you can identify with 100% certainty using at least three distinguishing features, such as cap color, gill structure, and spore print.

One of the most critical foraging guidelines is to avoid risky self-identification, especially as a beginner. Many toxic mushrooms closely resemble edible ones, and subtle differences can be easy to miss. For example, the False Chanterelle (*Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca*) looks similar to the edible Chanterelle but can cause gastrointestinal distress. Similarly, the Fool’s Funnel (*Clitocybe rivulosa*) mimics the edible Fairy Ring Champignon but is highly poisonous. If in doubt, leave it out—never consume a mushroom based on a guess or partial identification.

Another important aspect of safe foraging is to start small and focus on common, easily identifiable species. Begin with well-known edibles like the Oyster Mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) or Wood Blewit (*Clitocybe nuda*), which have fewer dangerous lookalikes. Gradually expand your knowledge as you gain experience. Always forage in clean, unpolluted areas away from roadsides, industrial sites, or agricultural land where mushrooms may absorb toxins. Additionally, respect nature by following the foraging code: take only what you need, avoid damaging habitats, and leave enough mushrooms to spore and regenerate.

Finally, document and verify your finds every time you forage. Take detailed notes, photographs, and, if possible, collect a spore print to aid identification. If you’re unsure about a mushroom, consult an expert before consuming it. Many local mycological societies offer identification services or host foraging events where you can learn and practice in a safe environment. Remember, foraging should be a rewarding and educational activity, but safety must always come first. By following expert advice, using reliable guides, and avoiding self-identification, you can enjoy the bounty of UK mushrooms without putting yourself at risk.

Should You Eat Psychedelic Mushroom Stems? A Practical Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Seasonal Availability: Know when safe mushrooms grow, e.g., autumn for Ceps and Oysters

Understanding the seasonal availability of safe-to-eat mushrooms in the UK is crucial for foragers and enthusiasts alike. Different mushroom species thrive in specific times of the year, influenced by factors like temperature, humidity, and daylight. For instance, autumn is a prime season for many edible mushrooms, making it a favorite time for foragers. During this season, Ceps (Porcini) and Oyster mushrooms are at their peak. Ceps, highly prized for their rich, nutty flavor, emerge in woodland areas, particularly under coniferous and deciduous trees. Oyster mushrooms, known for their delicate texture and mild taste, flourish on decaying wood, often found in clusters on fallen trees or stumps. Both species are abundant in the cooler, damp conditions of autumn, making it the ideal time to search for them.

Moving into late summer and early autumn, Chanterelles become a forager’s delight. These golden, trumpet-shaped mushrooms are found in woodland habitats, particularly under beech and oak trees. Their fruity aroma and meaty texture make them a culinary favorite, but their availability is strictly seasonal, typically from August to October. Similarly, Hedgehogs (Sweet Tooth Fungus) are another autumnal treat, recognizable by their spiky undersides. They grow in coniferous forests and are best harvested after the first frosts, which enhance their flavor. Knowing these specific windows of availability ensures that foragers can enjoy these mushrooms at their freshest and most flavorful.

Spring also offers its own selection of safe-to-eat mushrooms, though the variety is more limited compared to autumn. St George’s Mushrooms, named for their appearance around St. George’s Day (23rd April), are a springtime specialty. They grow in grassy areas, particularly in permanent pastures, and are easily identified by their creamy-white caps and distinct ring on the stem. Another spring find is the Dryad’s Saddle, though less commonly eaten due to its tough texture, it can be used for teas or when young and tender. Foraging in spring requires careful identification, as many mushrooms at this time are less familiar to casual foragers.

Summer is generally quieter for mushroom foraging in the UK, with fewer edible species available. However, Fairy Ring Champignons can be found in grassy areas, particularly in well-established lawns or meadows. These mushrooms form in circular patterns, giving them their name, and are best harvested young for a milder flavor. While summer may not be as bountiful as autumn, it still offers opportunities for those who know where and when to look.

Lastly, winter is the least productive season for mushroom foraging in the UK, with cold temperatures and frost limiting growth. However, Velvet Shank is a notable exception, thriving in winter conditions. Found on dead or decaying wood, particularly of broadleaf trees, this bright orange mushroom is a hardy species that can be foraged even in the coldest months. Its availability in winter makes it a unique find for those willing to brave the elements.

In summary, knowing the seasonal availability of safe-to-eat mushrooms in the UK is essential for successful and safe foraging. From the autumnal abundance of Ceps and Oysters to the springtime emergence of St George’s Mushrooms, each season offers its own unique opportunities. By aligning foraging trips with the natural cycles of these fungi, enthusiasts can enjoy a variety of edible mushrooms while minimizing the risk of misidentification. Always remember to forage responsibly, follow local regulations, and double-check identifications to ensure a safe and rewarding experience.

Raw Magic Mushrooms: Benefits, Risks, and Consumption Tips Explained

You may want to see also

Preparation Tips: Properly clean, cook, and store edible mushrooms to ensure safety

When preparing edible mushrooms in the UK, proper cleaning is the first crucial step to ensure safety and maintain their delicate flavor. Unlike cultivated mushrooms, wild varieties often carry dirt, debris, and even insects. Instead of soaking them in water, which can make them soggy, gently brush off dirt using a soft mushroom brush or a damp cloth. For stubborn particles, quickly rinse the mushrooms under cold running water and pat them dry with a clean kitchen towel or paper towels. This method preserves their texture and prevents them from absorbing excess moisture, which can dilute their flavor during cooking.

Cooking edible mushrooms correctly is essential to enhance their taste and eliminate any potential risks. Always cook wild mushrooms thoroughly, as some varieties may contain compounds that are harmful when raw. Sautéing, grilling, or roasting are excellent methods to bring out their rich flavors. Heat a pan with a small amount of butter or oil over medium heat, add the mushrooms, and cook until they are golden brown and any released moisture has evaporated. This process ensures they are safe to eat and develops a desirable texture. Avoid eating mushrooms raw, especially if you’re unsure about their origin or species, as some edible varieties can still cause discomfort when uncooked.

Proper storage is key to maintaining the freshness and safety of edible mushrooms. After cleaning, store them in a breathable container, such as a paper bag or a loosely covered bowl, in the refrigerator. Avoid airtight containers or plastic bags, as these can trap moisture and cause the mushrooms to spoil quickly. Fresh mushrooms should be consumed within 3 to 5 days for the best quality. If you have an excess, consider drying or freezing them for longer storage. To dry, slice the mushrooms thinly and place them in a dehydrator or a low-temperature oven until completely dry. For freezing, blanch the mushrooms briefly, cool them, and store them in airtight bags or containers for up to 6 months.

When handling wild mushrooms, always double-check their identification before preparation, even if you’re confident they are safe. Some toxic species closely resemble edible ones, and misidentification can lead to serious health risks. If in doubt, consult a mycologist or a reputable field guide. Additionally, avoid picking mushrooms from contaminated areas, such as roadside verges or industrial sites, as they may absorb harmful substances. Stick to clean, unpolluted environments when foraging.

Finally, be mindful of portion sizes and individual sensitivities when cooking with wild mushrooms. While many varieties are safe and delicious, some people may experience mild digestive discomfort when trying new types. Start with small quantities to test tolerance. Always cook mushrooms in a well-ventilated area, as the spores from some species can cause allergies or respiratory irritation in sensitive individuals. By following these preparation tips, you can safely enjoy the unique flavors and nutritional benefits of edible mushrooms in the UK.

Lion's Mane Mushrooms: Simple Preparation Tips for Delicious Culinary Use

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Common edible mushrooms in the UK include the Field Mushroom (*Agaricus campestris*), Chanterelles (*Cantharellus cibarius*), Oyster Mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), and Cep or Porcini (*Boletus edulis*).

Safely identifying edible mushrooms requires knowledge of key features like cap shape, gill structure, spore color, and habitat. Always use a reliable field guide or consult an expert, and avoid consuming any mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity.

Yes, several poisonous mushrooms in the UK resemble edible species. For example, the Deadly Webcap (*Cortinarius rubellus*) can be mistaken for a Chanterelle, and the Yellow Stainer (*Agaricus xanthodermus*) looks similar to the Field Mushroom.

While some mushrooms in gardens or parks may be edible, it’s risky to consume them without proper identification. Pollution, pesticides, or misidentification can pose serious health risks. Always exercise caution.

Foraging for mushrooms in the UK is generally legal on public land for personal use, but always check local regulations and respect private property. Some areas, like nature reserves, may have restrictions, and it’s important to forage sustainably by not over-harvesting.