Rhode Island, with its diverse ecosystems ranging from coastal forests to inland woodlands, provides an ideal habitat for a variety of mushroom species. The state's temperate climate and rich soil support both edible and non-edible fungi, making it a fascinating area for mycologists and foragers alike. Common mushrooms found in Rhode Island include the Chanterelle, known for its fruity aroma and golden color, and the Oyster Mushroom, which often grows on decaying wood. Additionally, the state is home to the iconic Morel, a prized find for its unique flavor and texture, as well as the ubiquitous Agaricus, or meadow mushroom, which thrives in grassy areas. However, foragers must exercise caution, as toxic species like the Amanita also inhabit the region, underscoring the importance of proper identification before consumption.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Common Edible Mushrooms

Rhode Island, with its diverse forests and temperate climate, is home to a variety of edible mushrooms that foragers can enjoy. Among the most common edible mushrooms found in the state are oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*). These mushrooms are easily recognizable by their fan-like, shell-shaped caps and grow in clusters on decaying wood, particularly hardwood trees like beech and oak. Oyster mushrooms have a mild, savory flavor and are a popular choice for cooking due to their versatility. They typically appear in the spring and fall, making these seasons ideal for foraging. Always ensure the mushrooms are firmly attached to wood and have a grayish to brownish cap to confirm their identity.

Another frequently found edible mushroom in Rhode Island is the lion's mane mushroom (*Hericium erinaceus*). This unique fungus resembles a cascading clump of white icicles or a lion's mane, hence its name. It grows on hardwood trees, often in late summer and fall. Lion's mane is prized for its seafood-like texture and mild, slightly sweet flavor, often compared to crab or lobster. When foraging, look for its distinctive appearance and ensure it is free from discoloration or insects. This mushroom is not only delicious but also valued for its potential cognitive health benefits.

The chanterelle (*Cantharellus cibarius*) is a highly sought-after edible mushroom that also grows in Rhode Island's forests. Recognizable by its golden-yellow color, wavy caps, and forked gills, chanterelles have a fruity aroma and a peppery, apricot-like flavor. They thrive in wooded areas, often near coniferous or hardwood trees, and are most commonly found in late summer and fall. When foraging, ensure the mushroom has a smooth stem and gills that fork and wrinkle rather than having distinct gills. Chanterelles are excellent in sauces, soups, and sautéed dishes.

For those new to foraging, the shaggy mane mushroom (*Coprinus comatus*) is a distinctive and edible species found in Rhode Island. This mushroom is tall and cylindrical with a shaggy, white cap that resembles a lawyer's wig. It grows in grassy areas, lawns, and disturbed soils, often appearing in late summer and fall. Shaggy manes are best harvested when young, as they quickly deliquesce (self-digest) as they mature. They have a delicate, slightly peppery flavor and are excellent in soups, omelets, or sautéed dishes. Always cook them promptly after harvesting to avoid their rapid decay.

Lastly, the chicken of the woods (*Laetiporus sulphureus*) is a vibrant and edible mushroom that grows in Rhode Island. This bracket fungus appears as large, fan-shaped clusters with bright orange-yellow caps and grows on hardwood trees, particularly oak. It is most commonly found in late summer and fall. Chicken of the woods gets its name from its texture and flavor, which resemble cooked chicken. When foraging, ensure the mushroom is young and pliable, as older specimens can become tough and unpalatable. Always cook it thoroughly to avoid potential digestive issues. This mushroom is a bold addition to stir-fries, tacos, and grilled dishes.

When foraging for edible mushrooms in Rhode Island, always follow best practices: positively identify mushrooms using multiple field guides or expert advice, avoid polluted areas, and never consume a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity. Happy and safe foraging!

Indiana's Edible Mushrooms: A Guide to Foraging Safely in the Wild

You may want to see also

Poisonous Species to Avoid

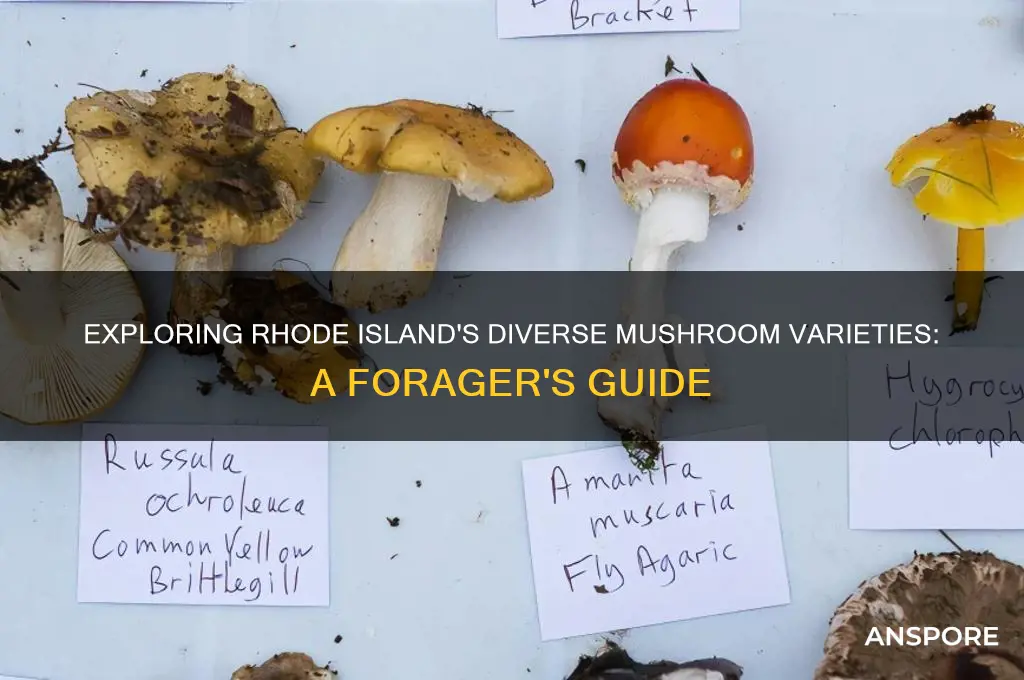

When foraging for mushrooms in Rhode Island, it is crucial to be aware of the poisonous species that can cause severe illness or even be fatal if ingested. One such species to avoid is the Destroying Angel (Amanita bisporigera), a deadly mushroom often found in wooded areas. It resembles edible species like the button mushroom, with its white cap and gills, but contains amatoxins that can cause liver and kidney failure. Even a small bite can be life-threatening, so always double-check any white-gilled mushrooms before consuming them.

Another dangerous species is the Deadly Galerina (Galerina marginata), which grows on wood and is often mistaken for edible honey mushrooms. Its small, brown cap and rusty-brown spores make it easy to overlook, but it contains the same amatoxins as the Destroying Angel. Symptoms of poisoning include severe gastrointestinal distress, dehydration, and potential organ failure. If you’re foraging near decaying wood, avoid any small brown mushrooms without proper identification.

The False Morel (Gyromitra spp.) is another poisonous mushroom found in Rhode Island, often confused with true morels due to its brain-like, wrinkled cap. However, it contains gyromitrin, a toxin that breaks down into a compound similar to rocket fuel. Cooking can reduce but not eliminate the toxin, and consumption can lead to severe gastrointestinal symptoms, seizures, and even death. Always ensure you are 100% certain when identifying morels, as the consequences of a mistake are dire.

Foragers should also be cautious of the Jack-O’-Lantern mushroom (Omphalotus olearius), which grows in clusters on decaying wood. Its bright orange to yellow-brown caps and bioluminescent properties make it striking, but it contains toxins that cause severe cramps, vomiting, and diarrhea. It is often mistaken for edible chanterelles, so pay close attention to the gills—Jack-O’-Lanterns have true gills, while chanterelles have forked ridges.

Lastly, the Conocybe filaris, also known as the Dung-loving Conocybe, is a small, nondescript mushroom that grows in grassy areas, often in lawns or pastures. It contains the same amatoxins as the Destroying Angel and Deadly Galerina, making it extremely dangerous. Its appearance is unassuming, with a small brown cap and slender stem, but its toxicity is not. Always avoid consuming small brown mushrooms unless you are absolutely certain of their identity. When in doubt, throw it out—no mushroom meal is worth risking your health.

Exploring Morel Mushrooms: Do They Thrive in France's Forests?

You may want to see also

Foraging Locations in RI

Rhode Island, despite its small size, offers a variety of habitats that support a diverse range of mushroom species. Foraging for mushrooms in RI can be a rewarding experience, but it’s essential to know where to look. Wooded areas are prime foraging locations, particularly those with deciduous trees like oak, beech, and maple. The George Washington Memorial Campground in Glocester is a great starting point, as its mixed forests provide ideal conditions for species such as chanterelles, oyster mushrooms, and hen of the woods (maitake). Always stick to trails and respect park rules to minimize environmental impact.

Another excellent foraging location in RI is Arcadia Management Area, one of the largest recreational areas in the state. Its extensive forests and wetlands create a fertile ground for mushrooms like lion’s mane, honey mushrooms, and even the elusive morels in spring. Focus on areas with decaying wood, as many fungi thrive on fallen logs and stumps. Bring a field guide or use a mushroom identification app to ensure you’re harvesting safely.

For coastal foragers, the Beavertail State Park in Jamestown offers a unique opportunity to find mushrooms that thrive in salt-spray environments. While less common, species like the seaside mushroom (*Agaricus bernardii*) can be found here. Pair your foraging with a visit to the park’s lighthouse for a scenic experience. Remember, coastal areas may have stricter regulations, so check local guidelines before collecting.

Urban foragers shouldn’t feel left out—Providence’s parks and green spaces can also yield surprises. Places like Roger Williams Park and Neutaconkanut Hill Park have enough wooded areas to support mushrooms like shiitakes and ink caps. However, be cautious of pollution in urban areas and avoid mushrooms growing near roadsides or industrial sites. Always wash urban finds thoroughly before consumption.

Lastly, Lincoln Woods State Park is a forager’s paradise with its dense forests and freshwater ponds. Here, you’re likely to find porcini (bolete) mushrooms, especially in late summer and early fall. Stick to the less-traveled paths to increase your chances of finding untouched patches. As with all foraging, practice sustainability by only taking what you need and leaving no trace. Rhode Island’s diverse landscapes make it a hidden gem for mushroom enthusiasts, but always prioritize safety and respect for nature.

Understanding Fae: Essential Techniques for Optimal Mushroom Cultivation Success

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Seasonal Growth Patterns

Rhode Island's temperate climate and diverse ecosystems provide a fertile ground for a variety of mushrooms, each with distinct seasonal growth patterns. Spring, particularly from April to June, marks the emergence of morel mushrooms (*Morchella* spp.), which are highly prized by foragers. These fungi thrive in moist, wooded areas with decaying organic matter, often appearing after the last frost when soil temperatures rise. Foragers should look for morels near deciduous trees like elms and ashes, as these mushrooms have a symbiotic relationship with such species. Early spring rains and warming temperatures create the ideal conditions for their fruiting bodies to develop, making this season crucial for morel enthusiasts.

As summer arrives, from July to August, the focus shifts to chanterelle mushrooms (*Cantharellus* spp.), which prefer warmer temperatures and well-drained soils. These golden fungi are commonly found in Rhode Island's oak and beech forests, where they form mycorrhizal associations with tree roots. Summer's higher humidity and occasional rainfall encourage chanterelle growth, though they are less abundant during dry spells. Foragers should explore forested areas with ample leaf litter and avoid over-harvesting to ensure sustainable populations. Additionally, the summer months may also see the appearance of oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), which grow on decaying wood and can be found in both natural and urban settings.

Autumn, from September to November, is arguably the most prolific season for mushroom growth in Rhode Island. This period sees the emergence of lion's mane mushrooms (*Hericium erinaceus*), which grow on hardwood trees and are known for their unique appearance and culinary value. Cooler temperatures and increased rainfall create optimal conditions for their development. Simultaneously, hen of the woods (*Grifola frondosa*) appears at the base of oak trees, forming large, clustered fruiting bodies. This season is also prime time for porcini or king bolete mushrooms (*Boletus edulis*), which are found in coniferous and deciduous forests. Autumn's combination of cooler weather and moist environments fosters a diverse array of mushroom species, making it a favorite season for foragers.

Winter, from December to March, is generally a dormant period for most mushroom species in Rhode Island due to cold temperatures and frozen ground. However, certain cold-tolerant varieties, such as the velvet foot mushroom (*Flammulina velutipes*), can still be found growing on dead or dying hardwood trees. These mushrooms are adapted to withstand frost and may fruit sporadically during warmer winter days. Foragers should exercise caution during this season, as the risk of misidentification is higher due to the limited variety of mushrooms available. Despite the reduced activity, winter provides an opportunity to study fungal mycelium and prepare for the upcoming spring foraging season.

Understanding these seasonal growth patterns is essential for successful and sustainable mushroom foraging in Rhode Island. Each season offers unique opportunities to discover different species, but it also requires awareness of environmental conditions and ethical harvesting practices. By aligning foraging activities with the natural cycles of fungi, enthusiasts can enjoy the bounty of Rhode Island's mushroom diversity while preserving these vital organisms for future generations.

Discovering the Unique Habitats Where Lobster Mushrooms Thrive Naturally

You may want to see also

Identification Tips & Tools

When identifying mushrooms in Rhode Island, it's essential to have a systematic approach and the right tools. Start by familiarizing yourself with the common species found in the region, such as oyster mushrooms, lion's mane, chicken of the woods, chanterelles, and morels. Each of these mushrooms has distinct characteristics, including cap shape, gill structure, spore color, and habitat preferences. For instance, oyster mushrooms typically grow on wood and have a fan-like shape, while morels are known for their honeycomb-like caps and preference for wooded areas.

Field guides are invaluable tools for mushroom identification. Look for guides specific to the Northeastern United States, such as *"Mushrooms of the Northeastern United States and Eastern Canada"* by Alan Bessette et al., which includes detailed descriptions and high-quality images of local species. When using a field guide, pay attention to key features like cap color, stem thickness, and whether the mushroom has gills, pores, or spines. Cross-referencing multiple guides can also help confirm identifications, as some species may be described differently across sources.

Mobile apps like iNaturalist and Mushroom ID can assist in real-time identification. These apps allow you to upload photos of mushrooms and receive community-based or AI-generated suggestions. However, always verify app results with other sources, as misidentifications can occur. Additionally, carrying a magnifying glass or loupe is crucial for examining microscopic features like spore color, which can be a decisive factor in identification. For example, chanterelles have false gills and release yellowish spores, while amanitas often have white spores.

Spore prints are another essential tool for identification. To create a spore print, place the cap of the mushroom gills-down on a piece of white or black paper (depending on spore color) and cover it with a bowl for several hours. The resulting spore deposit can reveal the mushroom's color, which is a critical identification feature. For instance, morels typically produce a creamy or yellowish spore print, while boletes often have olive or brown spores. Always handle mushrooms carefully during this process to avoid damaging their structures.

Lastly, consider joining local mycological clubs or foraging groups in Rhode Island. These communities offer hands-on learning opportunities, guided forays, and access to experienced identifiers who can help you refine your skills. Tools like a small knife for cutting mushrooms to examine their internal structure and a notebook for recording observations (e.g., habitat, smell, and color changes) are also essential. Remember, accurate identification is crucial, as some mushrooms in Rhode Island, like the deadly destroying angel, are toxic and can be mistaken for edible species. Always prioritize safety and never consume a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity.

Profitable Mushroom Farming: Unveiling the Earnings of a Mushroom Grower

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Common mushrooms found in Rhode Island include the Eastern Oyster Mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), Chicken of the Woods (*Laetiporus sulphureus*), Lion's Mane (*Hericium erinaceus*), and various species of Chanterelles (*Cantharellus* spp.).

Yes, Rhode Island is home to several poisonous mushrooms, such as the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*), Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*), and Jack-O-Lantern (*Omphalotus olearius*). Always consult an expert before consuming wild mushrooms.

The best time to forage for mushrooms in Rhode Island is during the late summer and fall months, typically from August through October, when moisture and temperature conditions are ideal for fungal growth.

While most mushrooms in Rhode Island are seasonal, some species like the Wood Ear (*Auricularia auricula-judae*) and certain bracket fungi can be found year-round, though availability depends on weather conditions.