Mushrooms that grow on mesquite trees are often associated with the unique ecological conditions provided by these drought-resistant trees, which are native to arid and semi-arid regions. Mesquite wood, rich in nutrients and often found in decomposing stages, serves as an ideal substrate for certain fungal species. Among the mushrooms commonly found on mesquite are various wood-decay fungi, such as species from the *Pleurotus* (oyster mushroom) and *Trametes* (turkey tail) genera, which play a crucial role in breaking down the tough lignin and cellulose in the wood. Additionally, some mycorrhizal fungi may form symbiotic relationships with mesquite roots, aiding in nutrient uptake. Understanding which mushrooms grow on mesquite not only sheds light on the tree’s ecological interactions but also highlights potential applications in forestry, agriculture, and even culinary uses, as some of these fungi are edible or have medicinal properties.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Types of Mesquite-Loving Mushrooms: Identify specific mushroom species commonly found growing on mesquite trees

- Habitat Requirements: Explore the environmental conditions mesquite trees provide for mushroom growth

- Edibility and Safety: Determine which mesquite-grown mushrooms are safe to eat and which are toxic

- Seasonal Growth Patterns: Understand when mushrooms typically grow on mesquite trees throughout the year

- Cultivation Techniques: Learn how to encourage mushroom growth on mesquite trees in controlled settings

Types of Mesquite-Loving Mushrooms: Identify specific mushroom species commonly found growing on mesquite trees

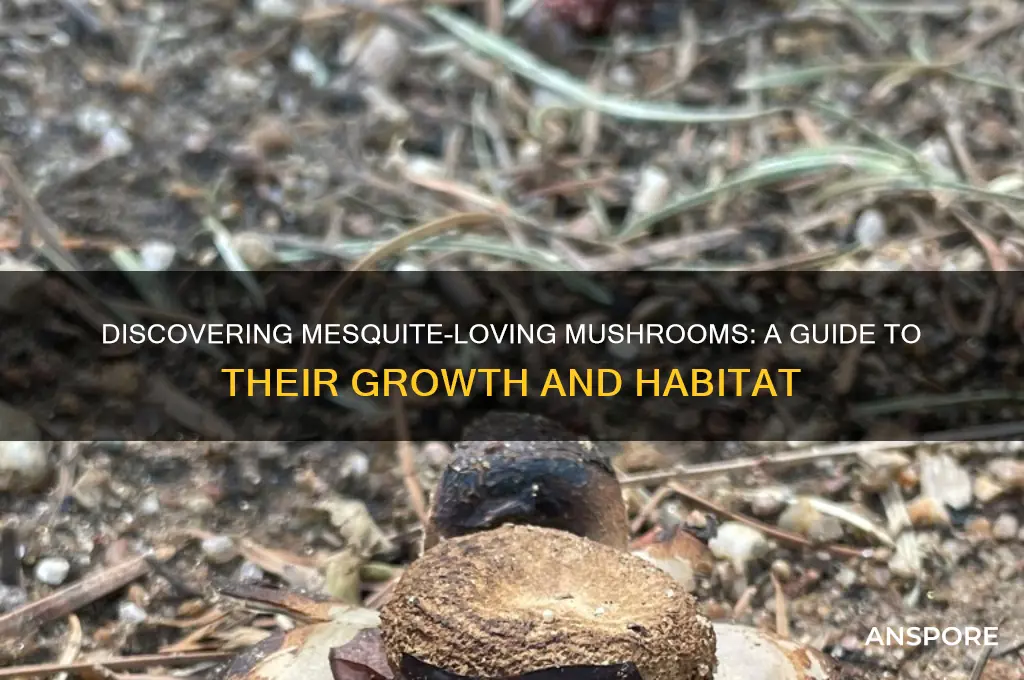

Mesquite trees, native to arid and semi-arid regions, particularly in the southwestern United States and Mexico, provide a unique habitat for various fungi. While mesquite is not typically associated with a wide variety of mushrooms compared to deciduous or coniferous trees, certain species have adapted to thrive in this environment. One notable mushroom that grows on mesquite is the Dye’s Mushroom (*Psathyrella dybowskii*), though it is not exclusive to mesquite. However, specific saprotrophic and mycorrhizal fungi are more commonly found in mesquite ecosystems. Identifying these mushrooms requires understanding their ecological roles and physical characteristics.

Among the mushrooms commonly found in mesquite habitats is the Mesquite Oyster Mushroom (*Pleurotus pulmonarius* var. *mesquites*), a variant of the common oyster mushroom. This species is saprotrophic, meaning it decomposes dead mesquite wood, and is recognizable by its fan-like caps, white to cream gills, and a mild, anise-like scent. It typically fruits in clusters on decaying logs or stumps, making it a valuable find for foragers in mesquite woodlands. Another species often encountered is the Mesquite Bracket Fungus (*Trametes versicolor* var. *mesquites*), a polypore fungus that forms shelf-like structures on dead or dying mesquite trees. Its vibrant, zoned colors and tough, woody texture make it easy to identify, though it is not edible.

In addition to these, Dung-Loving Inky Caps (*Coprinus spp.*) are frequently found near mesquite trees, particularly in areas where livestock graze. While not directly growing on mesquite, these mushrooms thrive in the enriched soil beneath the trees, often appearing after rains. Their delicate, ink-black caps and short lifespan are distinctive features. Another mesquite-associated species is the Desert Coral Mushroom (*Ramaria spp.*), which forms branching, coral-like structures in the soil near mesquite roots. These mushrooms are mycorrhizal, forming symbiotic relationships with the trees, and are typically bright orange or yellow, adding a splash of color to the arid landscape.

Foraging for mesquite-loving mushrooms requires caution, as some species can be toxic or difficult to identify. For instance, the False Morel (*Gyromitra spp.*) may occasionally appear in mesquite habitats and resembles edible morels but is highly poisonous. Always consult a field guide or expert before consuming any wild mushrooms. Additionally, the Mesquite Cup Fungus (*Peziza spp.*) is a saprotrophic species that forms cup-like structures on the ground near mesquite trees. While not typically edible, it plays a crucial role in nutrient cycling within the ecosystem.

Understanding the types of mushrooms that grow on or near mesquite trees not only aids in identification but also highlights the ecological importance of these fungi. From decomposers like the Mesquite Oyster Mushroom to symbiotic partners like the Desert Coral Mushroom, each species contributes to the health and diversity of mesquite ecosystems. By learning to recognize these mushrooms, enthusiasts can deepen their appreciation for the intricate relationships between fungi and their environment in arid regions.

Unveiling the Growth Secrets of Mushroom Coral: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Habitat Requirements: Explore the environmental conditions mesquite trees provide for mushroom growth

Mesquite trees, primarily found in arid and semi-arid regions of the Americas, create unique environmental conditions that can support the growth of specific mushroom species. These trees are well-adapted to harsh climates, often thriving in areas with poor soil quality, low rainfall, and high temperatures. The habitat requirements for mushrooms growing on mesquite are closely tied to the ecological characteristics of these trees. Mesquite trees have deep taproots that access groundwater, allowing them to survive in dry conditions, and their fallen leaves and decaying wood contribute to a nutrient-rich microenvironment at the soil surface. This organic matter provides a substrate for fungi to decompose and grow, making mesquite trees a potential host for certain mushroom species.

One of the key environmental conditions mesquite trees provide is a stable, warm climate. Mushrooms that grow on mesquite are often thermophilic, meaning they thrive in higher temperatures. The arid regions where mesquite trees are prevalent offer consistent warmth, which is essential for the fruiting bodies of these fungi to develop. Additionally, the shade provided by mesquite canopies creates a microclimate that moderates extreme temperatures, preventing the soil from becoming too hot or dry for fungal growth. This balance of warmth and moisture retention is critical for mushrooms that depend on mesquite habitats.

Soil composition around mesquite trees is another critical factor for mushroom growth. Mesquite trees fix nitrogen in the soil through symbiotic relationships with bacteria, enriching the substrate with essential nutrients. This nitrogen-rich environment supports the decomposition processes carried out by fungi, fostering mushroom development. The pH of the soil around mesquite trees is typically neutral to slightly alkaline, which aligns with the preferences of many mushroom species. Furthermore, the presence of mesquite leaf litter and wood debris creates a humus-rich layer that retains moisture, providing a suitable medium for mycelium to spread and fruit.

Moisture availability, though limited in mesquite habitats, is strategically utilized by mushrooms adapted to these conditions. Mesquite trees often grow in areas with sporadic rainfall, and their deep roots help channel water to the surface during rare precipitation events. Mushrooms growing on mesquite have evolved to take advantage of these brief periods of increased moisture, rapidly producing fruiting bodies before the soil dries out again. Some species may also form symbiotic relationships with mesquite roots, accessing water directly from the tree’s vascular system. This adaptation allows them to survive in an otherwise water-scarce environment.

Lastly, the symbiotic and saprophytic relationships between mushrooms and mesquite trees play a significant role in habitat requirements. Certain mushrooms form mutualistic associations with mesquite roots, aiding in nutrient uptake for the tree while receiving carbohydrates in return. Others act as decomposers, breaking down fallen mesquite wood and leaves to recycle nutrients back into the ecosystem. These relationships highlight the interdependence between mesquite trees and the fungi that grow on them, creating a specialized habitat that supports unique mushroom species. Understanding these environmental conditions is essential for identifying and cultivating mushrooms associated with mesquite trees.

Mastering Mushroom Cultivation: Crafting Effective Growing Blocks at Home

You may want to see also

Edibility and Safety: Determine which mesquite-grown mushrooms are safe to eat and which are toxic

When exploring the edibility and safety of mushrooms that grow on mesquite, it is crucial to approach the topic with caution and thorough research. Mesquite trees, primarily found in arid and semi-arid regions, can host a variety of fungi, but not all are safe for consumption. The first step in determining edibility is to identify the specific mushroom species growing on mesquite. Common species associated with mesquite include *Tricholoma resininaceum* (a type of gilled mushroom) and *Lentinula* species, though these are not exclusive to mesquite. Proper identification requires examining characteristics such as cap color, gill structure, spore print, and habitat. Misidentification can lead to severe consequences, as some toxic mushrooms resemble edible ones.

Among the mushrooms that grow on mesquite, certain species are known to be safe for consumption when correctly identified. For instance, *Lentinula* species, similar to shiitake mushrooms, are generally edible and prized for their culinary uses. However, it is essential to ensure that the mushroom in question is indeed a *Lentinula* species, as look-alikes can be toxic. Another potentially edible species is *Tricholoma resininaceum*, though its edibility can vary by region, and some individuals may experience mild gastrointestinal discomfort. Always cross-reference findings with reliable mycological guides or consult an expert before consuming any wild mushroom.

Conversely, several toxic mushrooms may also grow on or near mesquite trees, posing significant risks to foragers. One example is the *Amanita* genus, which includes deadly species like the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*). While *Amanita* species are not exclusive to mesquite, they can appear in similar habitats and are often mistaken for edible varieties. Another toxic group is the *Galerina* genus, which contains species that resemble small, innocuous mushrooms but contain deadly amatoxins. Symptoms of poisoning from these mushrooms can include severe gastrointestinal distress, organ failure, and even death, often appearing several hours after ingestion.

To ensure safety, foragers should adhere to strict guidelines when assessing mesquite-grown mushrooms. First, never consume a mushroom unless it has been positively identified by an expert or through multiple reliable sources. Second, avoid mushrooms with white gills, a volva (cup-like structure at the base), or those that bruise or stain easily, as these traits are common in toxic species. Third, always cook mushrooms thoroughly before consumption, as some toxins are destroyed by heat. Lastly, start with a small portion and wait 24 hours to check for adverse reactions before consuming more.

In conclusion, while some mushrooms growing on mesquite may be edible and delicious, the risks associated with misidentification are too great to ignore. Toxic species like *Amanita* and *Galerina* can be life-threatening, and their presence in similar habitats underscores the need for caution. By prioritizing accurate identification, consulting experts, and following safety protocols, foragers can minimize risks and enjoy the rewards of edible mesquite-grown mushrooms responsibly. Always remember: when in doubt, throw it out.

Prevent Mushroom Growth in Mulch: Effective Tips and Solutions

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$15.99 $19.99

Seasonal Growth Patterns: Understand when mushrooms typically grow on mesquite trees throughout the year

Mushrooms that grow on mesquite trees, primarily in arid and semi-arid regions, exhibit distinct seasonal growth patterns influenced by environmental factors such as temperature, humidity, and rainfall. Mesquite trees, being drought-resistant, thrive in regions with limited water, and the fungi associated with them have adapted to these conditions. The primary mushrooms found on mesquite include species like *Omphalotus olearius* (Jack-o’-lantern mushroom) and various wood-decay fungi such as *Trametes* and *Ganoderma* species. Understanding their seasonal growth patterns is crucial for foragers, ecologists, and enthusiasts alike.

During the spring months, mushroom growth on mesquite trees is generally limited due to the gradual warming of temperatures and inconsistent rainfall. However, this season marks the beginning of fungal activity as the soil moisture increases slightly from winter rains. Wood-decay fungi, such as *Trametes versicolor*, may start to appear on dead or decaying mesquite branches, as these fungi thrive on decomposing wood rather than living trees. Spring is not the peak season for mushroom growth on mesquite, but it serves as a preparatory phase for the more active periods ahead.

Summer is the most challenging season for mushroom growth on mesquite trees due to the extreme heat and arid conditions prevalent in their native habitats. Most fungi require moisture to fruit, and the dry summer months often inhibit this process. However, after sporadic summer rains or monsoonal activity, certain resilient species may emerge. For instance, *Omphalotus olearius*, a bioluminescent mushroom, can occasionally appear on mesquite trees following heavy rainfall, though such occurrences are rare and short-lived. Summer growth is highly dependent on unpredictable weather patterns and is not consistent year-to-year.

Fall is the prime season for mushroom growth on mesquite trees, particularly in regions with distinct wet and dry cycles. As temperatures cool and rainfall becomes more consistent, fungi take advantage of the increased moisture and milder conditions. Wood-decay fungi like *Ganoderma* species, often referred to as bracket fungi, are commonly observed on mesquite during this time. These fungi form shelf-like structures on the bark and wood of the tree, playing a vital role in nutrient cycling. Foragers should be cautious, as some mushrooms growing on mesquite, like the Jack-o’-lantern mushroom, are toxic and can be mistaken for edible species.

In winter, mushroom growth on mesquite trees slows significantly due to cooler temperatures and reduced fungal activity. However, in regions with mild winters and occasional rainfall, some wood-decay fungi may persist, especially on dead or fallen mesquite branches. Winter is a dormant period for most fungi, but it allows for the accumulation of organic matter and the preparation of the substrate for the next growing season. This seasonal lull is essential for the ecological balance and long-term health of the mesquite ecosystem.

In summary, the seasonal growth patterns of mushrooms on mesquite trees are closely tied to environmental conditions, with fall being the most productive season. Spring and winter show limited fungal activity, while summer growth is rare and dependent on rainfall. Understanding these patterns not only aids in the identification and appreciation of these fungi but also highlights their ecological significance in arid environments. Foraging or studying these mushrooms should always be done with caution and respect for their natural habitat.

Mastering Shiitake Cultivation: A South African Grower's Guide

You may want to see also

Cultivation Techniques: Learn how to encourage mushroom growth on mesquite trees in controlled settings

Mesquite trees, native to arid regions, can host a variety of mushrooms, particularly those adapted to woody substrates. To cultivate mushrooms on mesquite in controlled settings, start by selecting the appropriate mushroom species. Research indicates that oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) and certain wood-degrading fungi like *Trametes* species are well-suited for mesquite wood due to its dense, hardwood nature. These mushrooms thrive on lignin and cellulose, which mesquite provides in abundance. Ensure the mesquite wood is aged and free from chemicals, as fresh-cut wood may inhibit mycelial growth.

The next step involves preparing the mesquite substrate. Cut the mesquite into small chips or sawdust to increase surface area, facilitating faster colonization by the mushroom mycelium. Sterilize the substrate using steam or pasteurization to eliminate competing microorganisms. For sterilization, steam the mesquite chips at 160°F (71°C) for 1-2 hours. Alternatively, pasteurization at 140°F (60°C) for 1-2 hours is less harsh and can preserve some beneficial microbes. After cooling, inoculate the substrate with mushroom spawn, ensuring even distribution. Use a ratio of 5-10% spawn to substrate by weight for optimal results.

Maintaining the right environmental conditions is critical for successful mushroom cultivation on mesquite. Mushrooms require high humidity (85-95%) and moderate temperatures (60-75°F or 15-24°C). Use a humidifier or misting system to keep the air moist, and ensure proper ventilation to prevent mold growth. Light exposure is minimal, but indirect light can stimulate fruiting. Monitor the substrate’s moisture content, keeping it damp but not waterlogged. Regularly inspect for contamination and address any issues promptly.

Fruiting induction is a key phase in the cultivation process. Once the mycelium fully colonizes the mesquite substrate (typically 2-4 weeks), initiate fruiting by exposing the colonized substrate to cooler temperatures (55-65°F or 13-18°C) and fresh air exchange. This simulates the natural transition to fruiting conditions. Mist the surface lightly to encourage pinhead formation, which will develop into mature mushrooms. Harvest when the caps are fully open but before spores are released to ensure optimal quality.

For long-term cultivation, consider creating a controlled environment like a grow tent or room. Use a combination of heating, cooling, and humidification systems to maintain stable conditions. Reuse partially spent mesquite substrate by replenishing nutrients or supplementing with fresh material to extend productivity. Experiment with different mushroom species to diversify your yield and adapt techniques based on their specific requirements. With patience and attention to detail, cultivating mushrooms on mesquite in controlled settings can be a rewarding and sustainable practice.

Why Mushrooms Suddenly Appear in Your Home: Causes and Solutions

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mushrooms that grow on mesquite trees are often saprophytic or parasitic species. Common examples include *Omphalotus olearius* (Jack-o’-lantern mushroom), *Laetiporus sulphureus* (chicken of the woods), and various species of *Pycnoporus* (polypores). These fungi typically thrive on decaying wood.

Not all mushrooms growing on mesquite are safe to eat. Some, like the Jack-o’-lantern mushroom, are toxic and can cause severe gastrointestinal issues. Always consult a mycologist or field guide before consuming wild mushrooms.

Identification involves examining characteristics like cap shape, color, gills or pores, and spore print. Look for bright colors (e.g., orange or yellow in *Laetiporus*) or bioluminescence (in *Omphalotus*). Using a mushroom identification guide or app can also help.