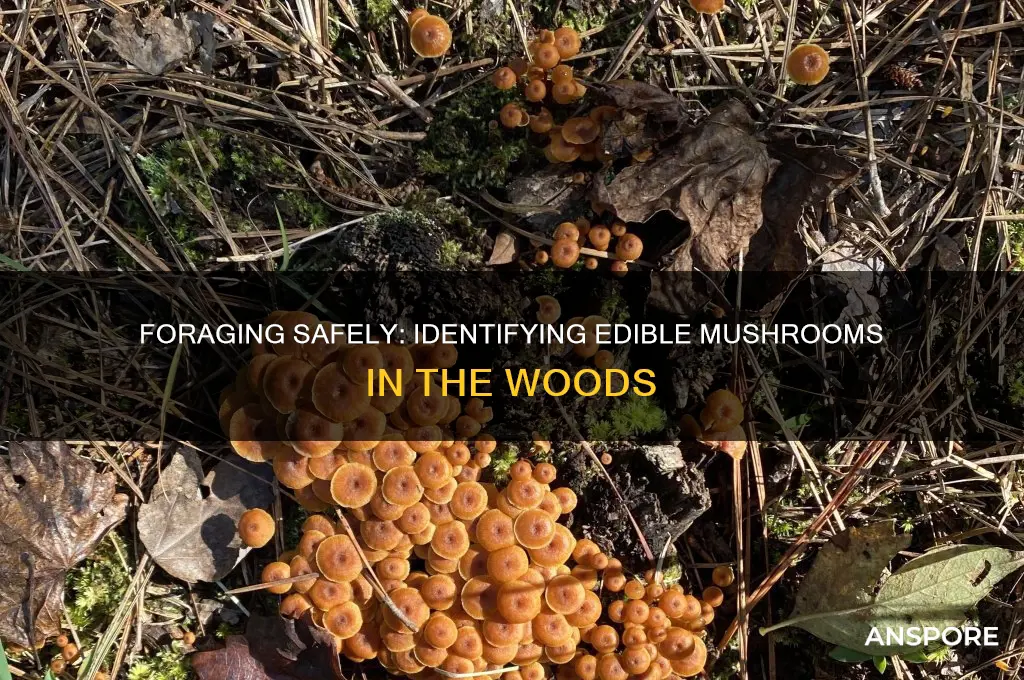

Exploring the woods in search of edible mushrooms can be a rewarding yet challenging endeavor, as it requires knowledge, caution, and respect for nature. While forests are home to a diverse array of fungi, only a select few are safe to eat, and misidentification can lead to serious health risks. Common edible varieties include chanterelles, known for their golden hue and fruity aroma; morels, prized for their honeycomb-like caps and rich flavor; and porcini, celebrated for their meaty texture and nutty taste. However, it’s crucial to familiarize oneself with toxic look-alikes, such as the deadly Amanita species, and to consult reliable guides or experts before foraging. Always ensure mushrooms are properly cooked, as some edible species can cause discomfort when raw. Responsible foraging also involves respecting the ecosystem by leaving some mushrooms behind to spore and avoiding over-harvesting. With the right approach, discovering edible mushrooms in the woods can be a delicious and sustainable way to connect with nature.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Common Name | Chanterelle, Morel, Porcini (Cep), Lion's Mane, Oyster Mushroom, Chicken of the Woods, Shaggy Mane, Hedgehog Mushroom, Cauliflower Mushroom, Lobster Mushroom |

| Scientific Name | Cantharellus cibarius, Morchella spp., Boletus edulis, Hericium erinaceus, Pleurotus ostreatus, Laetiporus sulphureus, Coprinus comatus, Hydnum repandum, Sparassis crispa, Hypomyces lactifluorum |

| Edibility | All are edible when properly identified and prepared |

| Habitat | Forests, woodlands, under trees (oak, beech, pine), decaying wood |

| Season | Chanterelle: Summer-Fall, Morel: Spring, Porcini: Fall, Lion's Mane: Late Summer-Fall, Oyster: Year-round (depending on region), Chicken of the Woods: Summer-Fall, Shaggy Mane: Late Summer-Fall, Hedgehog: Fall, Cauliflower: Fall, Lobster: Late Summer-Fall |

| Cap Shape | Conical (Chanterelle), Honeycomb (Morel), Round/Cushion (Porcini), Spiny (Lion's Mane), Fan/Shell (Oyster), Shelf-like (Chicken of the Woods), Bell/Conical (Shaggy Mane), Spiny (Hedgehog), Branched (Cauliflower), Deformed (Lobster) |

| Color | Golden-yellow (Chanterelle), Brown/Tan (Morel), Brown (Porcini), White/Cream (Lion's Mane), Gray/Brown (Oyster), Bright Orange/Yellow (Chicken of the Woods), White (Shaggy Mane), Cream/Yellow (Hedgehog), White/Cream (Cauliflower), Red/Orange (Lobster) |

| Gills/Pores | Forked gills (Chanterelle), Hollow (Morel), Pores (Porcini), Spines (Lion's Mane), Gills (Oyster), None (Chicken of the Woods), Gills (Shaggy Mane), Teeth/Spines (Hedgehog), Branched (Cauliflower), None (Lobster) |

| Stem | Tapered (Chanterelle), Hollow (Morel), Thick (Porcini), Absent/Short (Lion's Mane), Lateral (Oyster), Absent (Chicken of the Woods), Tall/Slender (Shaggy Mane), Short (Hedgehog), Absent (Cauliflower), Absent (Lobster) |

| Texture | Chewy (Chanterelle), Meaty (Morel), Firm (Porcini), Tender (Lion's Mane), Chewy (Oyster), Tender (Chicken of the Woods), Delicate (Shaggy Mane), Crunchy (Hedgehog), Chewy (Cauliflower), Chewy (Lobster) |

| Taste | Fruity/Apricot (Chanterelle), Earthy/Nuts (Morel), Nutty/Woody (Porcini), Crab/Lobster (Lion's Mane), Mild/Anise (Oyster), Chicken-like (Chicken of the Woods), Mild (Shaggy Mane), Sweet/Nutty (Hedgehog), Mild/Earthy (Cauliflower), Seafood-like (Lobster) |

| Aroma | Fruity/Apricot (Chanterelle), Earthy (Morel), Nutty (Porcini), Seafood (Lion's Mane), Anise (Oyster), Mild (Chicken of the Woods), Earthy (Shaggy Mane), Fruity (Hedgehog), Mild (Cauliflower), Seafood (Lobster) |

| Look-alikes | False Chanterelle (Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca), False Morel (Gyromitra spp.), Bitter Bolete (Tylopilus felleus), Tooth fungi (non-edible species), Poisonous shelf fungi, Inky Cap (non-edible species), Poisonous hedgehog fungi, Non-edible branched fungi, Poisonous red mushrooms |

| Preparation Tips | Sauté, grill, dry, or use in soups/sauces |

| Caution | Always verify identification with an expert or field guide. Some mushrooms require cooking to be safe. Avoid consuming alcohol with certain species. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Identifying Safe Mushrooms: Learn key features to distinguish edible from poisonous mushrooms in the wild

- Common Edible Varieties: Discover popular edible mushrooms like chanterelles, morels, and oyster mushrooms

- Toxic Look-Alikes: Beware of poisonous mushrooms that closely resemble edible species, such as false morels

- Foraging Tips: Best practices for safely harvesting mushrooms, including tools and seasonal timing

- Cooking Edible Mushrooms: Simple and delicious recipes to prepare wild mushrooms for meals

Identifying Safe Mushrooms: Learn key features to distinguish edible from poisonous mushrooms in the wild

Foraging for mushrooms in the woods can be a rewarding experience, but it’s crucial to know how to identify safe species. Mistaking a poisonous mushroom for an edible one can have severe, even fatal, consequences. Key features such as cap shape, gill structure, spore color, and stem characteristics serve as critical identifiers. For instance, the chanterelle, prized for its fruity aroma and forked gills, is a safe bet, while the deceptively similar jack-o’-lantern mushroom, with its sharp gills and bioluminescent properties, is toxic. Learning these distinctions is not just a skill—it’s a necessity for any forager.

One analytical approach to identifying safe mushrooms involves examining their ecological relationships. Mycorrhizal mushrooms, like porcini and morels, form symbiotic partnerships with trees and are generally safe to eat. In contrast, saprobic mushrooms, which decompose organic matter, include both edible species (e.g., oyster mushrooms) and deadly ones (e.g., the destroying angel). Understanding these categories narrows down the possibilities but isn’t foolproof. Always cross-reference multiple features, such as the presence of a skirt-like ring on the stem or the color of the spore print, to confirm edibility.

A persuasive argument for caution lies in the deceptive nature of some poisonous mushrooms. The Amanita genus, for example, includes species that resemble common edible mushrooms like the meadow mushroom. However, Amanitas often have a distinctive cup-like volva at the base of the stem and white spore prints, both red flags for toxicity. Even experienced foragers can be fooled, so carrying a field guide or using a mushroom identification app is essential. Remember: when in doubt, throw it out.

Comparatively, edible mushrooms often exhibit consistent traits that set them apart. Lion’s mane mushrooms, for instance, have cascading, icicle-like spines instead of gills, a unique feature that makes them easy to identify. Similarly, chicken of the woods grows in bright orange-yellow fan-shaped clusters on trees and has a texture reminiscent of cooked chicken. These distinct characteristics reduce the risk of confusion with toxic species. However, always check for look-alikes, such as the poisonous false chicken of the woods, which grows on yew trees and can cause severe reactions.

Practically, mastering mushroom identification requires hands-on experience and a systematic approach. Start by focusing on a few common edible species, like the birch bolete or the cauliflower mushroom, and learn their key features. Practice making spore prints by placing the cap gills-down on paper overnight—edible species like the shiitake produce white to brown spores, while toxic ones may produce green or black. Additionally, note environmental factors: edible mushrooms often grow in specific habitats, such as oyster mushrooms on decaying wood or morels in disturbed soil. With time, patience, and a critical eye, you’ll develop the expertise to safely enjoy the bounty of the woods.

Chewing Mushrooms: To Swallow or Spit Out? Exploring the Effects

You may want to see also

Common Edible Varieties: Discover popular edible mushrooms like chanterelles, morels, and oyster mushrooms

Foraging for mushrooms in the woods can be a rewarding endeavor, but it’s crucial to know which varieties are safe to eat. Among the most sought-after edible mushrooms are chanterelles, morels, and oyster mushrooms, each prized for their distinct flavors and textures. These fungi not only elevate culinary dishes but also thrive in diverse woodland environments, making them accessible to foragers across different regions. However, proper identification is paramount, as some toxic species closely resemble these edible treasures.

Chanterelles, often referred to as "golden chanterelles," are a forager’s delight with their vibrant yellow-orange hue and forked, wavy caps. They grow in deciduous and coniferous forests, particularly under oak and beech trees. Their fruity, apricot-like aroma and chewy texture make them a favorite in sauces, soups, and sautéed dishes. When harvesting, ensure the gills are forked and not straight, as this distinguishes them from poisonous look-alikes like the jack-o’lantern mushroom. Always cut the stem at the base to encourage regrowth.

Morels are another highly prized woodland mushroom, celebrated for their honeycomb-like caps and earthy, nutty flavor. They typically emerge in spring, favoring disturbed soil near ash, elm, and aspen trees. Their unique appearance makes them relatively easy to identify, but beware of false morels, which have a brain-like, wrinkled cap and can be toxic. Morels are best enjoyed sautéed or in creamy sauces, and they pair exceptionally well with meats and eggs. Always cook morels thoroughly, as consuming them raw can cause digestive discomfort.

Oyster mushrooms, named for their shell-like appearance, are versatile and widely available, growing on dead or dying hardwood trees. Their mild, anise-like flavor and tender texture make them a kitchen staple, ideal for stir-fries, soups, and even as a meat substitute. Unlike chanterelles and morels, oyster mushrooms are easier to cultivate, but foraging them in the wild requires careful inspection to avoid confusing them with poisonous species like the angel wings mushroom. Look for their fan-shaped caps and decurrent gills, which run down the stem.

In conclusion, chanterelles, morels, and oyster mushrooms are not only culinary gems but also symbols of the forest’s bounty. Each variety offers a unique foraging experience and flavor profile, but their identification demands attention to detail. Armed with knowledge and caution, foragers can safely enjoy these edible treasures, transforming woodland walks into gourmet adventures. Always consult a field guide or expert when in doubt, and remember: when it comes to mushrooms, certainty is the key to a safe and delicious harvest.

Shiitake vs. Dried Black Mushrooms: Perfect Substitute or Different Flavor?

You may want to see also

Toxic Look-Alikes: Beware of poisonous mushrooms that closely resemble edible species, such as false morels

In the shadowy understory of the woods, where edible mushrooms like morels and chanterelles beckon foragers, a sinister mimicry unfolds. False morels (*Gyromitra esculenta*), with their brain-like folds and earthy allure, closely resemble their edible counterparts but harbor a toxic secret: gyromitrin, a compound that converts to monomethylhydrazine, a potent toxin. Ingesting even small amounts can lead to severe gastrointestinal distress, seizures, or worse. Foragers must scrutinize the stem—true morels are hollow, while false morels are chambered—and avoid the temptation to taste-test, as toxicity is not always immediate.

The danger of toxic look-alikes extends beyond false morels. The deadly galerina (*Galerina marginata*), often mistaken for edible honey mushrooms (*Armillaria mellea*), contains amatoxins, which cause liver and kidney failure within 24–48 hours. Unlike many poisons, amatoxins are not neutralized by cooking, drying, or freezing. A single cap can be lethal, and symptoms may not appear until irreversible damage has begun. Foragers should note the galerina’s rusty-brown spores and persistent ring on the stem, absent in honey mushrooms.

Even experienced foragers can fall victim to the jack-o’-lantern mushroom (*Omphalotus olearius*), a glowing imposter of the edible chanterelle. While its bioluminescent gills are a giveaway, its bright orange color and wavy caps often deceive in daylight. The jack-o’-lantern contains illudins, which cause severe cramps, vomiting, and dehydration, though rarely death. Unlike chanterelles, which have forked gills and a fruity aroma, the jack-o’-lantern’s gills are sharply veined and smell musky. Always carry a spore print kit—the jack-o’-lantern’s spores are green-brown, while chanterelles’ are yellow.

To navigate this minefield, adopt a three-step verification process: identification, cross-referencing, and expert consultation. First, use field guides or apps to identify key features (gill structure, spore color, habitat). Second, cross-reference findings with multiple sources, noting discrepancies. Third, consult a mycologist or local foraging group before consuming. Avoid foraging solo and carry a first-aid kit with activated charcoal, which can bind toxins in the stomach if ingestion is suspected. Remember, no meal is worth risking your life—when in doubt, throw it out.

Exploring Psilocybin Mushrooms as a Potential Anxiety Treatment Option

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$14.4 $18.95

Foraging Tips: Best practices for safely harvesting mushrooms, including tools and seasonal timing

Mushrooms are nature's hidden treasures, but not all are safe to eat. Before venturing into the woods, arm yourself with knowledge and the right tools. A good field guide, preferably one with detailed illustrations and descriptions, is essential. Apps like iNaturalist can also aid in identification, but always cross-reference findings with multiple sources. Foraging isn’t just about spotting mushrooms; it’s about understanding their habitats, look-alikes, and seasonal patterns. For instance, chanterelles thrive in wooded areas with oak and pine trees, while morels prefer disturbed soil after forest fires or logging. Knowing these nuances can turn a novice forager into a confident harvester.

Timing is everything in mushroom foraging. Most edible species have specific seasons tied to climate and geography. In North America, morels typically appear in spring, while porcini and chanterelles dominate late summer to fall. Coastal regions may see a longer season due to milder temperatures, whereas inland areas have shorter, more intense bursts. Always check local conditions and consult regional foraging groups for up-to-date information. Harvesting at the right time ensures not only the best flavor but also the safety of the mushroom, as older specimens can degrade or become infested with insects.

Proper tools make foraging safer and more sustainable. A sharp knife is crucial for cleanly cutting mushrooms at the base, preserving the mycelium for future growth. A basket or mesh bag allows spores to disperse as you walk, aiding forest regeneration. Avoid plastic bags, which can cause mushrooms to sweat and spoil. Wear gloves to protect against irritants like poison ivy and carry a small notebook to document locations and species. Foraging ethically means taking only what you need and leaving no trace—a practice that ensures these resources remain for years to come.

Caution is paramount when foraging. Even experienced foragers double-check identifications, as toxic species often resemble edible ones. For example, the deadly galerina can be mistaken for honey mushrooms, and false morels mimic true morels. If in doubt, leave it out. Start by learning a few easily identifiable species, like lion’s mane or chicken of the woods, before tackling more complex varieties. Never eat a mushroom raw unless you’re certain it’s safe, as some require cooking to neutralize toxins. Finally, always cook a small portion first and wait 24 hours to ensure no adverse reactions occur.

Foraging is as much about connection as it is about harvest. Take time to observe the forest ecosystem—notice how mushrooms interact with trees, soil, and wildlife. This mindfulness not only enhances your foraging skills but also deepens your respect for nature. Share your knowledge with others, but do so responsibly, emphasizing the importance of conservation and safety. With the right approach, mushroom foraging becomes a rewarding practice that nourishes both body and soul.

Can Rats Safely Eat Raw Baby Bella Mushrooms? A Guide

You may want to see also

Cooking Edible Mushrooms: Simple and delicious recipes to prepare wild mushrooms for meals

Foraging for wild mushrooms can be a rewarding adventure, but knowing how to cook them transforms these forest finds into culinary treasures. Among the most sought-after edible varieties are chanterelles, known for their apricot-like aroma and golden hue; porcini, prized for their meaty texture and nutty flavor; and morels, with their honeycomb caps and earthy depth. Each mushroom brings a unique profile to the table, making them versatile ingredients for both simple and sophisticated dishes.

One of the easiest and most flavorful ways to prepare wild mushrooms is by sautéing. Start by cleaning the mushrooms gently with a brush or damp cloth to remove dirt, avoiding water to preserve their texture. Heat a tablespoon of butter or olive oil in a pan over medium heat, add thinly sliced garlic, and sauté until fragrant. Toss in the mushrooms, ensuring they’re in a single layer for even cooking. Season with salt, pepper, and a sprinkle of fresh thyme or parsley. Cook until they’re golden brown and slightly crispy, about 5–7 minutes. This method highlights their natural flavors and pairs perfectly with grilled meats, pasta, or crusty bread.

For a heartier dish, try stuffing wild mushrooms like portobellos or large porcini caps. Preheat your oven to 375°F (190°C). Remove the stems and gills from the mushroom caps, then brush them with olive oil and place them gill-side up on a baking sheet. In a bowl, mix breadcrumbs, grated Parmesan, minced garlic, chopped spinach, and a drizzle of olive oil. Spoon the mixture into the caps and bake for 20–25 minutes, or until the mushrooms are tender and the stuffing is golden. This recipe is not only delicious but also a great way to elevate a vegetarian meal.

If you’re looking to preserve the season’s bounty, drying mushrooms is a practical and flavorful option. Clean the mushrooms and slice them thinly, then spread them on a baking sheet lined with parchment paper. Dry them in the oven at its lowest setting (around 150°F or 65°C) for 2–3 hours, or until they’re completely dry and brittle. Store them in an airtight container, and rehydrate in warm water or broth when ready to use. Dried mushrooms intensify in flavor, making them perfect for soups, risottos, or sauces.

Always exercise caution when foraging and cooking wild mushrooms. Misidentification can lead to serious illness, so consult a field guide or expert if unsure. Once you’ve safely gathered your haul, these simple recipes will help you savor the forest’s gifts in every bite. From sautéing to stuffing to preserving, wild mushrooms offer endless possibilities for creative and delicious meals.

Can You Can Chicken of the Woods Mushrooms? A Preservation Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Always consult a reliable field guide or a mycologist. Look for key features like cap shape, gill color, spore print, and habitat. Avoid mushrooms with white gills, a bulbous base, or those that bruise easily, as these traits are common in poisonous species.

Yes, some common edible mushrooms include Chanterelles (golden, wavy caps), Morel mushrooms (honeycomb-like caps), and Lion’s Mane (shaggy, white appearance). Always double-check identification before consuming.

If in doubt, throw it out. Never eat a mushroom unless you are 100% certain it is safe. Some poisonous mushrooms closely resemble edible ones, and misidentification can be fatal. When in doubt, consult an expert.