When foraging for mushrooms, it's crucial to know which ones to avoid, as some species can be highly toxic or even deadly. Common poisonous mushrooms include the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*), which resembles edible varieties and causes severe liver damage; the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*), often mistaken for chanterelles or puffballs; and the Conocybe filaris, a small, nondescript mushroom that can be lethal. Additionally, the False Morel (*Gyromitra esculenta*) contains a toxin that can cause severe gastrointestinal distress and, in extreme cases, organ failure. Always consult a reliable field guide or expert before consuming wild mushrooms, as misidentification can have serious consequences.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Deadly Galerina: Mimics honey mushrooms, grows on wood, causes organ failure if ingested

- Destroying Angels: Pure white, often mistaken for edible, extremely toxic, fatal if eaten

- False Morels: Brain-like appearance, toxic when raw, can cause severe illness or death

- Poisonous Amanitas: Bright colors, often red or white, contain deadly amatoxins, avoid entirely

- Little Brown Mushrooms (LBMs): Hard to identify, many toxic species, best left untouched

Deadly Galerina: Mimics honey mushrooms, grows on wood, causes organ failure if ingested

The Deadly Galerina, scientifically known as *Galerina marginata*, is a highly toxic mushroom that poses a significant risk to foragers due to its deceptive appearance. Often mistaken for edible honey mushrooms (*Armillaria* species), this fungus is a dangerous imposter that can lead to severe poisoning and even death if ingested. Its ability to mimic harmless varieties makes it one of the most treacherous mushrooms in the wild.

This toxic fungus typically grows on wood, favoring decaying stumps and logs in forests. It has a small to medium-sized cap, usually brown or tan, with a distinctive slimy surface when moist. The gills underneath are closely spaced and can vary from pale yellow to rusty brown. One of its most misleading features is its appearance during the same season as honey mushrooms, often in similar habitats, making it an easy mistake for even experienced foragers.

The toxicity of the Deadly Galerina lies in its amatoxins, a group of cyclic octapeptides that cause severe liver and kidney damage. Symptoms of poisoning may not appear for 6-24 hours after ingestion, starting with gastrointestinal issues like diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. As the toxins take effect, the damage progresses to acute liver and kidney failure, which can be fatal without immediate medical intervention. The insidious nature of these symptoms, combined with the mushroom's unassuming appearance, has earned it a reputation as a silent killer.

Foraging for mushrooms requires extreme caution, and the Deadly Galerina is a prime example of why proper identification is crucial. Always consult multiple field guides and, if possible, seek advice from mycologists or experienced foragers. When in doubt, it is best to err on the side of caution and avoid consuming any mushroom that could be confused with this deadly species. Remember, the consequences of misidentification can be irreversible.

In summary, the Deadly Galerina is a wood-dwelling mushroom that mimics the edible honey fungus, making it a significant threat to those who forage without expert knowledge. Its toxins can cause severe organ failure, and its deceptive appearance has led to numerous cases of accidental poisoning. Education and awareness are key to avoiding this dangerous mushroom, ensuring that foragers can enjoy the bounty of the forest without putting their lives at risk. Always approach mushroom hunting with respect and caution, as the line between a delicious meal and a deadly mistake can be alarmingly thin.

Discover the Health Benefits of Eating Shiitake Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Destroying Angels: Pure white, often mistaken for edible, extremely toxic, fatal if eaten

The Destroying Angels are a group of mushrooms that belong to the genus *Amanita* and are among the most deadly fungi in the world. These mushrooms are pure white, with a striking appearance that often leads foragers to mistake them for edible species like the common button mushroom or the meadow mushroom. However, this similarity is a dangerous deception, as Destroying Angels contain potent toxins, including amatoxins, which can cause severe liver and kidney damage, often leading to death if consumed. Their pristine white color, which includes the cap, gills, and stem, makes them stand out in the forest, but this beauty is a warning sign that should never be ignored.

One of the most treacherous aspects of Destroying Angels is their resemblance to edible mushrooms, especially when young or in the "button" stage. Foragers, particularly those who are inexperienced, may be drawn to their clean, unblemished appearance, assuming they are safe to eat. This mistake can be fatal, as even a small bite is enough to cause severe poisoning. Symptoms of amatoxin poisoning typically appear 6 to 24 hours after ingestion and include vomiting, diarrhea, dehydration, and, in severe cases, liver failure. Immediate medical attention is crucial, but even with treatment, the outcome can be fatal.

Identifying Destroying Angels requires careful observation of specific characteristics. They have a smooth, white cap that ranges from 5 to 15 cm in diameter, a bulbous base on the stem, and a ring (partial veil) on the upper stem. The gills are white and closely spaced, and the spores are also white, which can be verified by placing the cap on paper overnight. However, relying on these features alone is risky, as some variations within the species may exist. The safest approach is to avoid any pure white mushrooms altogether, especially those with a bulbous base and a ring, as these are hallmark features of Destroying Angels.

Habitat plays a role in their identification as well. Destroying Angels are mycorrhizal, meaning they form symbiotic relationships with trees, and are commonly found in wooded areas, particularly under conifers and deciduous trees. They thrive in temperate regions of North America, Europe, and Asia, often appearing in late summer and fall. Despite their widespread presence, their toxicity makes them a species to avoid entirely. No culinary or medicinal value justifies the risk of misidentification.

Education and awareness are key to preventing accidental poisoning by Destroying Angels. Foragers should always cross-reference multiple field guides, consult experts, and, when in doubt, leave the mushroom untouched. The old adage "there are old foragers and bold foragers, but no old, bold foragers" rings especially true with these mushrooms. Their pure white beauty is a siren call that must be resisted, as the consequences of consuming them are irreversible and deadly. Always prioritize caution and respect for the natural world when exploring fungi in the wild.

Do Mushrooms Eat Yeast? Unraveling the Fungal Food Chain Mystery

You may want to see also

False Morels: Brain-like appearance, toxic when raw, can cause severe illness or death

False Morels, scientifically known as *Gyromitra esculenta*, are a group of mushrooms that can be extremely deceptive due to their resemblance to edible morels. Their brain-like appearance, characterized by wrinkled, convoluted caps, often lures foragers into a false sense of security. However, consuming False Morels, especially when raw, can lead to severe illness or even death. Unlike true morels, which are highly prized in culinary circles, False Morels contain a toxic compound called gyromitrin, which breaks down into monomethylhydrazine, a potent toxin. This toxin affects the nervous system and can cause symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and in severe cases, seizures or organ failure.

One of the most critical points to remember about False Morels is that their toxicity is not always neutralized by cooking. While some sources suggest that thorough cooking can break down gyromitrin, this process is unreliable and risky. Even experienced foragers and mycologists advise against consuming False Morels under any circumstances. The potential for error in preparation, combined with the variability in toxin levels between individual mushrooms, makes them far too dangerous to justify their consumption. It is always better to err on the side of caution and avoid them entirely.

Identifying False Morels correctly is crucial for anyone foraging mushrooms. Unlike true morels, which have a hollow stem and cap, False Morels often have a cottony, brittle, or partially solid interior. Their caps are typically more rounded and brain-like, with folds that do not form the distinct honeycomb pattern of true morels. Additionally, False Morels often grow in coniferous forests and appear earlier in the season than true morels. If you are unsure about a mushroom's identity, it is best to leave it alone, as misidentification can have deadly consequences.

The symptoms of False Morel poisoning can appear within hours of ingestion and may initially resemble food poisoning. However, the condition can rapidly deteriorate, leading to more severe neurological symptoms. Immediate medical attention is essential if poisoning is suspected. Treatment may include gastric lavage, activated charcoal, and supportive care to manage symptoms and prevent complications. Public awareness about the dangers of False Morels is vital, as many cases of poisoning occur due to a lack of knowledge or misinformation about their toxicity.

In conclusion, False Morels are a prime example of why proper identification is critical when foraging mushrooms. Their brain-like appearance may seem intriguing, but their toxic nature makes them one of the most dangerous mushrooms to encounter. Always exercise caution, educate yourself about mushroom identification, and consult reliable guides or experts when in doubt. Avoiding False Morels altogether is the safest approach to ensure your well-being and that of others. Remember, when it comes to mushrooms, it is better to admire them in nature than to risk your health by consuming them.

Eating Rotten Mushrooms: Risks, Symptoms, and When to Seek Help

You may want to see also

Explore related products

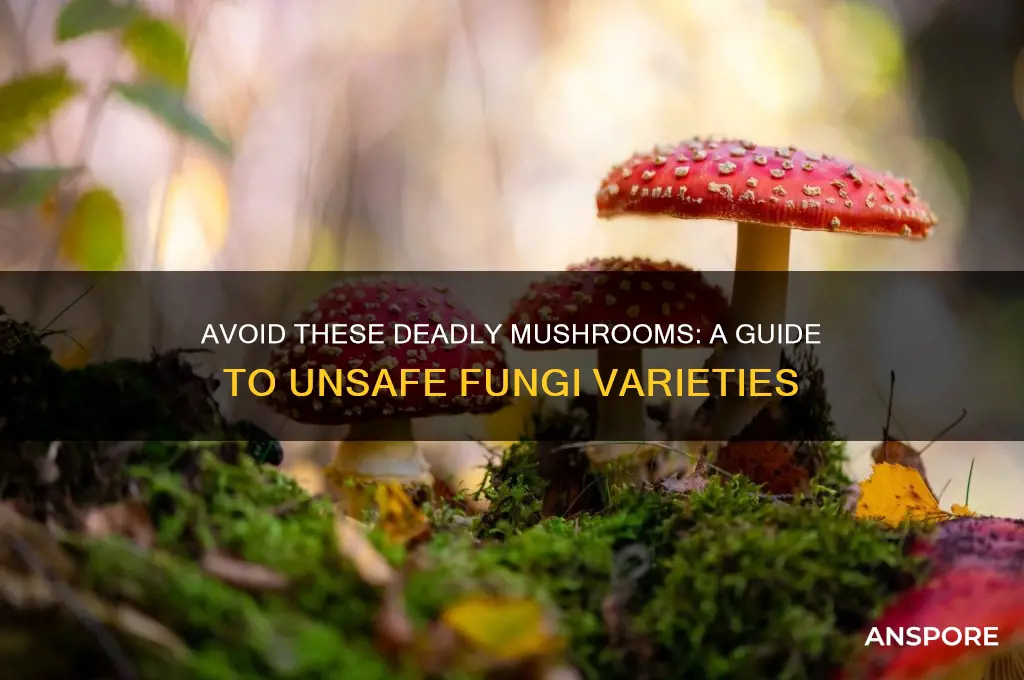

Poisonous Amanitas: Bright colors, often red or white, contain deadly amatoxins, avoid entirely

When foraging for mushrooms, it's crucial to be aware of the Poisonous Amanitas, a group of highly toxic fungi that can cause severe illness or even death. These mushrooms are characterized by their bright colors, often red or white, which serve as a warning sign in nature. The Amanitas contain deadly amatoxins, which are among the most potent toxins found in the fungal kingdom. Even a small amount ingested can lead to liver and kidney failure, making them extremely dangerous. Therefore, it is imperative to avoid Amanitas entirely and never consume them under any circumstances.

One of the most notorious species in this group is the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*), which is responsible for the majority of fatal mushroom poisonings worldwide. Despite its ominous name, the Death Cap can be deceivingly attractive, with a pale green or yellowish cap and a sturdy white stalk. Another dangerous relative is the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera* and *Amanita ocreata*), which is pure white and often mistaken for edible button mushrooms. Their innocent appearance belies their lethal nature, as they contain the same deadly amatoxins. Always remember: bright red or white mushrooms, especially those resembling Amanitas, should never be touched or tasted.

Identifying Amanitas requires careful observation of their key features. Look for a cap with white or colored patches (warts), a skirt-like ring on the stem, and a bulbous base that often resembles an egg in younger specimens. These characteristics, combined with their striking colors, are red flags. If you encounter a mushroom with these traits, do not handle it without gloves, as some toxins can be absorbed through the skin. Instead, leave it undisturbed and continue your search for safe, edible species.

It's important to note that Amanitas often grow in the same environments as edible mushrooms, such as woodlands and grassy areas, increasing the risk of accidental ingestion. Novice foragers are particularly vulnerable, as they may mistake a Poisonous Amanita for an edible variety like the Meadow Mushroom or Chanterelle. Always cross-reference findings with reliable guides or consult an expert before consuming any wild mushroom. When in doubt, throw it out—no meal is worth risking your life.

Finally, education is your best defense against Amanita poisoning. Familiarize yourself with their appearance and habitats, and teach others, especially children, to avoid bright red or white mushrooms. If you suspect Amanita ingestion, seek medical attention immediately, as symptoms may not appear for 6–24 hours, delaying treatment can be fatal. Remember, the mantra for Amanitas is clear: bright colors, deadly toxins, avoid entirely. Stay safe and enjoy the beauty of mushrooms from a distance.

Mushroom-Eating Flies: Decomposers or Just Opportunistic Feeders?

You may want to see also

Little Brown Mushrooms (LBMs): Hard to identify, many toxic species, best left untouched

Little Brown Mushrooms, commonly referred to as LBMs, are a group of fungi that share a nondescript brown coloration and often grow in various habitats, from forests to lawns. While their appearance may seem innocuous, LBMs are notoriously difficult to identify accurately due to their lack of distinctive features. Many species within this group have similar shapes, sizes, and textures, making it nearly impossible for even experienced foragers to distinguish between edible and toxic varieties without microscopic examination or advanced knowledge. This ambiguity is a significant red flag for anyone considering consuming them.

One of the most critical reasons to avoid LBMs is the high prevalence of toxic species within this group. Some LBMs contain potent toxins that can cause severe gastrointestinal distress, organ failure, or even death if ingested. For example, the Deadly Galerina (Galerina marginata) is a toxic LBM often mistaken for edible species like the Honey Mushroom. Similarly, the Conocybe filaris, another toxic LBM, has been responsible for fatal poisonings. Without definitive identification tools, the risk of accidentally consuming a toxic LBM is unacceptably high, making it safer to leave them untouched.

The challenge of identifying LBMs extends beyond their physical appearance. Many toxic and edible species within this group also share similar habitats and growing conditions, further complicating the task for foragers. Even characteristics like spore color, gill structure, or odor, which are sometimes used to identify mushrooms, can be inconsistent or overlapping among LBMs. This lack of reliable field markers underscores the importance of avoiding them altogether, as misidentification can have dire consequences.

Foraging guides and experts consistently advise against collecting or consuming LBMs due to these risks. While some experienced mycologists may be able to identify specific LBM species, the margin for error is too great for casual foragers. The principle of "when in doubt, leave it out" is particularly relevant here, as the potential rewards of finding an edible LBM do not outweigh the risks associated with toxic species. Instead, foragers are encouraged to focus on more easily identifiable mushrooms with distinct features and well-documented safety profiles.

In conclusion, Little Brown Mushrooms (LBMs) are best left untouched due to their difficulty in identification and the high number of toxic species within the group. Their bland appearance masks significant dangers, and the lack of reliable field identification methods makes them a gamble not worth taking. Foraging should always prioritize safety, and in the case of LBMs, the safest choice is to admire them in their natural habitat without attempting to harvest or consume them.

Is It Safe to Eat White Mushroom Raw? A Quick Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Avoid mushrooms with white gills, a bulbous base, or a ring on the stem, as these traits are common in toxic species like the Death Cap (Amanita phalloides). Always consult a field guide or expert for accurate identification.

Not necessarily, but many toxic mushrooms have vivid colors (red, yellow, or green). However, some edible mushrooms are also brightly colored, so color alone is not a reliable indicator.

It’s risky to eat wild mushrooms without proper identification. Many toxic species, like the Destroying Angel (Amanita bisporigera), grow in yards and gardens. Always verify with an expert before consuming.

No, cooking or boiling does not neutralize most mushroom toxins. Toxic compounds in poisonous mushrooms remain harmful even after preparation, so avoid consuming any unidentified species.