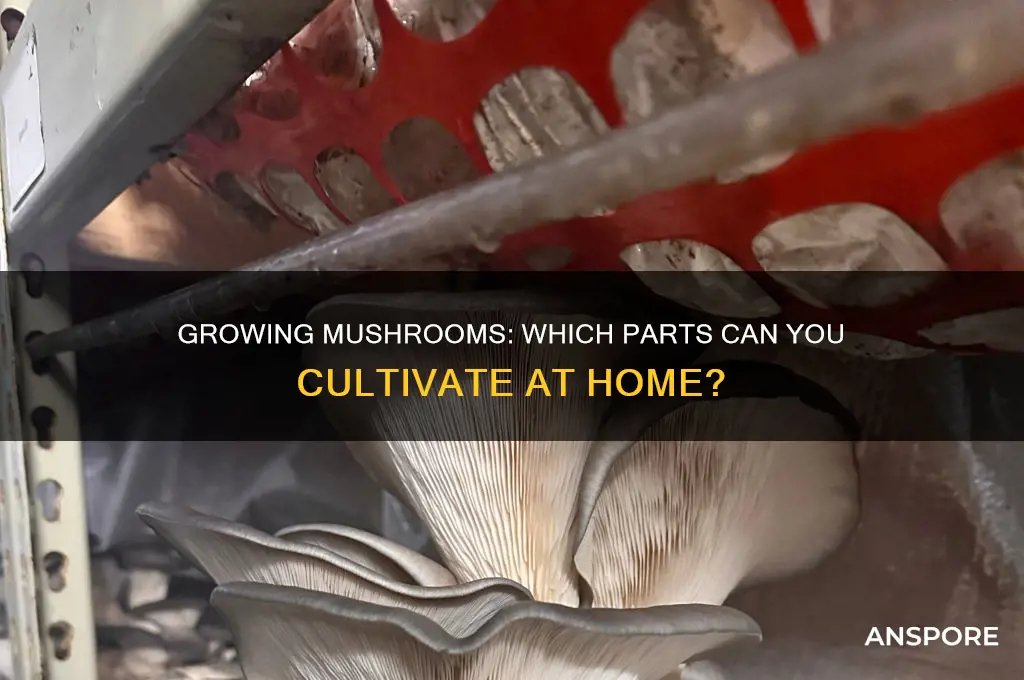

Mushrooms are fascinating organisms, and understanding which parts can be cultivated is key to successful mushroom growing. While the visible fruiting body is what most people recognize, it’s actually the mycelium—the network of thread-like cells beneath the surface—that serves as the foundation for growth. Mycelium can be cultivated from spores, tissue samples, or even store-bought mushrooms, depending on the species. For instance, oyster mushrooms can often be grown from the stem base, while other varieties require spore inoculation. By nurturing the mycelium in a suitable substrate, such as sawdust or grain, growers can encourage the development of new fruiting bodies, making it the essential part of the mushroom to focus on for cultivation.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Part of Mushroom | Mycelium |

| Description | The vegetative part of a fungus, consisting of a network of fine white filaments (hyphae). It is the primary mode of vegetative growth and nutrient absorption. |

| Growth Medium | Substrate (e.g., sawdust, straw, grain, or compost) enriched with nutrients. |

| Propagation Method | Mycelium can be propagated through spore germination, tissue culture, or cloning from existing mycelium. |

| Growth Conditions | Requires specific temperature (typically 20-28°C), humidity (60-80%), and pH levels (5.5-6.5) depending on the species. |

| Time to Fruiting | Varies by species, but generally takes 2-6 weeks after mycelium colonization of the substrate. |

| Common Species Grown | Shiitake, Oyster, Lion's Mane, Reishi, and Button mushrooms. |

| Harvestable Part | Fruiting bodies (mushrooms) that develop from the mycelium under specific environmental triggers (e.g., light, temperature shift). |

| Sustainability | Mycelium can be reused or expanded for multiple growth cycles, making it a sustainable cultivation method. |

| Challenges | Contamination risk from bacteria, molds, or other fungi; requires sterile techniques for successful cultivation. |

Explore related products

$14.99

What You'll Learn

- Mycelium: The root-like structure, essential for mushroom growth, can be cultivated from spores or tissue

- Spores: Tiny reproductive cells used to grow mushrooms, requiring specific conditions to germinate

- Tissue Culture: Growing mushrooms from small pieces of mushroom flesh or mycelium in labs

- Liquid Culture: Mycelium grown in nutrient-rich liquid, often used for faster mushroom cultivation

- Grain Spawn: Mycelium cultivated on grains like rye or wheat, a common growing medium

Mycelium: The root-like structure, essential for mushroom growth, can be cultivated from spores or tissue

Mycelium, often referred to as the "root system" of mushrooms, is the hidden engine driving fungal growth. This intricate network of thread-like filaments, called hyphae, spreads through soil or substrate, absorbing nutrients and preparing the stage for mushroom fruiting. While mushrooms themselves are the visible, reproductive structures, mycelium is the vital, often unseen, foundation.

Understanding mycelium is crucial for anyone interested in cultivating mushrooms. Unlike plants, which grow from seeds, mushrooms sprout from this network.

Cultivating mycelium is the first step in mushroom farming. There are two primary methods: spore inoculation and tissue culture. Spore inoculation involves capturing spores from a mature mushroom cap and introducing them to a sterile substrate like grain or agar. Under optimal conditions (darkness, warmth, moisture), spores germinate and develop into mycelium. This method is slower and less predictable, as spores represent the mushroom's sexual reproduction, leading to genetic variation. Tissue culture, on the other hand, uses a small piece of living mycelium from a healthy mushroom as a starting point. This method is faster and ensures genetic consistency, as the new mycelium is a clone of the parent.

Once established, mycelium colonizes the substrate, breaking down complex materials into nutrients. This process, known as mycelial growth, is essential for the eventual formation of mushrooms.

For the home cultivator, creating a suitable environment for mycelium is key. Sterility is paramount during inoculation to prevent contamination by competing molds or bacteria. Maintaining proper temperature (typically 70-75°F) and humidity (around 60-70%) encourages healthy mycelial growth. Patience is also essential; mycelium colonization can take weeks, depending on the mushroom species and substrate.

Daily Mushroom Coffee: Safe, Beneficial, or Overhyped? Let's Explore

You may want to see also

Spores: Tiny reproductive cells used to grow mushrooms, requiring specific conditions to germinate

Spores are the microscopic, dust-like seeds of the mushroom world, capable of developing into new fungi under the right conditions. Unlike seeds from plants, spores are incredibly resilient, surviving harsh environments until they find a suitable substrate to germinate. This adaptability makes them the primary method for mushroom propagation in both natural ecosystems and controlled cultivation settings. However, their tiny size and specific requirements mean that growing mushrooms from spores is both an art and a science.

To successfully cultivate mushrooms from spores, you must first understand their needs. Spores require a sterile environment to prevent contamination from bacteria or mold. This often involves using a spore syringe to inject spores into a nutrient-rich substrate, such as agar or grain, which has been sterilized in a pressure cooker. The substrate must be kept at the optimal temperature for the specific mushroom species, typically between 70°F and 75°F (21°C and 24°C). Humidity levels around 90% are also crucial during the initial stages of growth. These conditions mimic the damp, warm environments where mushrooms naturally thrive.

One of the challenges of working with spores is their unpredictability. While they are abundant—a single mushroom can release millions of spores—only a fraction will germinate successfully. This is why experienced growers often use spore syringes in conjunction with techniques like agar work, where spores are first cultivated on a petri dish before being transferred to a bulk substrate. This two-step process increases the chances of successful colonization and reduces the risk of contamination. For beginners, starting with a spore kit can simplify the process, providing pre-sterilized materials and step-by-step instructions.

Comparing spore cultivation to other methods, such as growing from mycelium (the vegetative part of the fungus), highlights its pros and cons. Spores offer genetic diversity, allowing growers to experiment with different strains and potentially discover unique varieties. However, the process is slower and more labor-intensive than using mycelium, which is already partially developed. For those seeking a quicker harvest, mycelium-based methods like grow kits are often preferred. Yet, for enthusiasts interested in the full lifecycle of mushrooms, spores provide an unparalleled opportunity to witness the entire growth process from start to finish.

In conclusion, spores are the foundation of mushroom cultivation, offering both challenges and rewards. Their tiny size belies their potential, but harnessing that potential requires patience, precision, and a willingness to learn. Whether you're a hobbyist or a professional grower, understanding the specific conditions spores need to germinate is key to unlocking their full potential. With the right tools and techniques, even beginners can turn these microscopic cells into thriving mushroom colonies.

Can Shiitake Mushrooms Thrive on Alder Logs? A Cultivation Guide

You may want to see also

Tissue Culture: Growing mushrooms from small pieces of mushroom flesh or mycelium in labs

Mushrooms, with their intricate mycelial networks, can be cultivated from various parts, but tissue culture stands out as a precise, lab-based method. Unlike traditional spore-based cultivation, tissue culture relies on small pieces of mushroom flesh or mycelium, offering a controlled environment for growth. This technique is particularly valuable for preserving rare or endangered species, as it allows for the propagation of genetically identical individuals. By isolating a tiny fragment—often no larger than a few millimeters—scientists can initiate a new culture, ensuring consistency and purity in the resulting mushrooms.

The process begins with sterilization, a critical step to prevent contamination. The mushroom tissue is carefully excised and placed in a sterile nutrient medium, typically containing agar, sugars, and essential minerals. The medium’s pH is adjusted to 5.5–6.0, optimal for mycelial growth. Under aseptic conditions, the tissue is incubated at 22–26°C, with humidity maintained at 60–70%. Over 7–14 days, the mycelium expands, forming a dense, white mat. This stage requires meticulous monitoring to detect and address any signs of contamination, such as mold or bacterial growth.

One of the advantages of tissue culture is its scalability. Once a healthy culture is established, it can be subcultured repeatedly, producing large quantities of mycelium for commercial or research purposes. For instance, oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) grown via tissue culture can yield up to 1 kg of fresh mushrooms per 100 grams of initial mycelium within 4–6 weeks. This efficiency makes tissue culture an attractive option for farmers seeking consistent, high-quality crops. However, the initial setup requires specialized equipment, including laminar flow hoods and autoclaves, which can be a barrier for small-scale growers.

Despite its benefits, tissue culture is not without challenges. Contamination remains a persistent risk, as even a single spore or bacterium can outcompete the mycelium. Additionally, the technique is less forgiving than traditional methods, demanding strict adherence to protocols. For hobbyists, starting with a tissue culture kit—available from suppliers like Fungi Perfecti—can simplify the process. These kits include pre-sterilized media and detailed instructions, reducing the learning curve. For advanced growers, experimenting with different nutrient formulations or growth conditions can optimize yields and explore new mushroom varieties.

In conclusion, tissue culture represents a cutting-edge approach to mushroom cultivation, blending precision with potential. While it requires initial investment and technical skill, its ability to produce uniform, contaminant-free cultures makes it invaluable for both research and agriculture. Whether preserving biodiversity or scaling up production, this method showcases the intersection of biology and innovation, offering a glimpse into the future of fungi farming.

How to Make a Reishi Mushroom Tincture at Home: A Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Liquid Culture: Mycelium grown in nutrient-rich liquid, often used for faster mushroom cultivation

Liquid culture is a game-changer for mushroom cultivators seeking efficiency and speed. By suspending mycelium in a nutrient-rich liquid medium, growers can achieve exponential growth rates compared to traditional methods. This technique leverages the mycelium's natural ability to thrive in aqueous environments, allowing it to multiply rapidly before being transferred to a bulk substrate. For instance, a single syringe of liquid culture can inoculate up to 10 jars of grain spawn, significantly reducing the time and effort required to scale up production.

The process begins with sterilizing a liquid nutrient solution, typically composed of water, sugar, and vitamins, which provides the mycelium with the energy and resources it needs to proliferate. Once cooled, the solution is inoculated with a small amount of mycelium, often from a spore syringe or agar plate. Over 7–14 days, the mycelium colonizes the liquid, creating a milky suspension that can be used to inoculate bulk substrates like straw, wood chips, or grain. This method bypasses the slower colonization phase of solid substrates, shaving weeks off the cultivation timeline.

One of the key advantages of liquid culture is its versatility. It can be used for a wide range of mushroom species, from oyster mushrooms to lion’s mane, making it a favorite among both hobbyists and commercial growers. However, precision is critical. The liquid medium must be sterilized properly to prevent contamination, and the pH should be maintained between 5.5 and 6.5 for optimal mycelial growth. Additionally, shaking or aerating the culture periodically ensures even distribution of nutrients and prevents the mycelium from clumping.

Despite its benefits, liquid culture is not without challenges. Contamination risks are higher due to the liquid medium’s susceptibility to bacteria and mold. Growers must adhere to strict sterile techniques, such as using a still-air box and flame-sterilizing tools. Another consideration is the need for specialized equipment, like a pressure cooker for sterilization and a magnetic stirrer for aeration, which may be cost-prohibitive for beginners. However, for those willing to invest time and resources, the payoff is a robust, fast-growing mycelium network ready to produce abundant fruiting bodies.

In practice, liquid culture is best suited for intermediate to advanced growers who have mastered the basics of sterile technique. Beginners might start with simpler methods like agar-to-grain transfers before graduating to liquid culture. For those ready to take the plunge, starting with a small batch and scaling up gradually can mitigate risks while building confidence. With its ability to accelerate growth and streamline production, liquid culture stands as a testament to the ingenuity of modern mushroom cultivation.

Slow-Cooked Perfection: Caramelizing Onions and Mushrooms in a Crock Pot

You may want to see also

Grain Spawn: Mycelium cultivated on grains like rye or wheat, a common growing medium

Grain spawn serves as a foundational medium for cultivating mycelium, the vegetative part of a fungus, which is essential for growing mushrooms. Unlike growing directly from spores or liquid cultures, grain spawn provides a nutrient-rich substrate that accelerates mycelial colonization. Rye and wheat are preferred grains due to their high starch content, which fuels rapid mycelium growth. This method is particularly effective for species like shiitake, oyster, and lion’s mane mushrooms, which thrive on grain-based substrates.

To create grain spawn, start by selecting organic rye or wheat berries, as they are free from chemical inhibitors that could hinder mycelium development. Sterilize the grains in a pressure cooker at 15 psi for 90 minutes to eliminate contaminants. Once cooled, inoculate the grains with a spore syringe or liquid culture, ensuring even distribution. Maintain a sterile environment during this process to prevent bacterial or mold contamination. After inoculation, incubate the grains in a dark, warm area (70–75°F) for 7–14 days, allowing the mycelium to fully colonize the substrate.

One of the advantages of grain spawn is its versatility. It can be used directly in bulk substrates like straw or sawdust or expanded further into larger batches of grain spawn. For example, a 5-pound bag of colonized grain spawn can inoculate up to 50 pounds of straw, making it a cost-effective method for large-scale mushroom cultivation. However, grain spawn requires careful monitoring to avoid contamination, as its dense structure can trap moisture and create ideal conditions for competing organisms.

Compared to other spawn types, such as sawdust or plug spawn, grain spawn offers faster colonization times and higher mycelial density. This makes it ideal for growers seeking quick results or those working with species that require robust mycelial networks. However, its shorter shelf life—typically 2–4 weeks when refrigerated—means it must be used promptly or stored under optimal conditions. For hobbyists, starting with 1–2 pounds of grain spawn per project is sufficient, while commercial growers may require larger quantities to meet production demands.

In conclusion, grain spawn is a powerful tool for mushroom cultivation, leveraging the nutrient density of rye or wheat to foster vigorous mycelium growth. By following precise sterilization and inoculation techniques, growers can harness its benefits to produce healthy, abundant mushroom yields. Whether for small-scale experimentation or large-scale farming, grain spawn remains a cornerstone of modern mycological practices.

Can Moldy Mushrooms Make You Sick? Risks and Symptoms Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

You can grow mushrooms from the mycelium, which is the vegetative part of the fungus that forms a network of thread-like structures.

No, mushroom caps are the fruiting bodies and do not contain the necessary mycelium to start a new growth cycle.

Yes, spores can be used to grow mushrooms, but they require specific conditions and are typically used in advanced cultivation methods rather than beginner setups.