Poisonous mushrooms exert their toxic effects by interacting with specific receptors in the human body, often leading to severe symptoms ranging from gastrointestinal distress to organ failure or even death. These mushrooms produce a variety of toxins, such as amatoxins, orellanine, and muscarine, which target different physiological systems. For instance, amatoxins, found in the deadly *Amanita* species, inhibit RNA polymerase II, disrupting protein synthesis in liver and kidney cells. Muscarine, present in mushrooms like *Clitocybe* species, acts as an agonist on muscarinic acetylcholine receptors, causing excessive stimulation of the parasympathetic nervous system. Orellanine, found in *Cortinarius* species, damages kidney tubules by interfering with cellular metabolism. Understanding the specific receptors and mechanisms these toxins act upon is crucial for developing effective treatments and antidotes, as well as for educating the public about the dangers of consuming unidentified mushrooms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Receptor Type | Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChRs), specifically M1 and M3 subtypes |

| Mechanism of Action | Agonism (activation) of mAChRs leading to excessive cholinergic stimulation |

| Toxins Involved | Muscarine, ibotenic acid, muscimol |

| Mushroom Species | Clitocybe dealbata, Inocybe spp., Clitocybe rivulosa, Amanita muscaria |

| Symptoms | Excessive salivation, sweating, tears, diarrhea, abdominal cramps, blurred vision, bronchial secretions |

| Onset of Symptoms | 15 minutes to 2 hours after ingestion |

| Treatment | Atropine (anticholinergic) to block mAChR activation |

| Additional Receptors | NMDA receptors (glutamate receptors) affected by ibotenic acid and muscimol |

| Secondary Effects | CNS depression, hallucinations, seizures (due to NMDA receptor interaction) |

| Fatality Risk | Generally low for muscarinic toxins; higher risk with NMDA-affecting toxins if untreated |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Nervous System Receptors: Mushrooms like Amanita target acetylcholine receptors, causing paralysis and respiratory failure

- GABA Receptors: Some toxins inhibit GABA receptors, leading to seizures and neurological symptoms

- Muscarinic Receptors: Muscarine-containing mushrooms overstimulate these receptors, causing sweating and vision issues

- Serotonin Receptors: Psilocybin binds to serotonin receptors, altering mood, perception, and cognition

- Ryanodine Receptors: Amatoxins disrupt calcium regulation via ryanodine receptors, causing liver and kidney damage

Nervous System Receptors: Mushrooms like Amanita target acetylcholine receptors, causing paralysis and respiratory failure

Poisonous mushrooms like *Amanita* species exert their deadly effects by targeting specific receptors in the nervous system, particularly acetylcholine receptors. These receptors are crucial for nerve signaling, muscle movement, and respiratory function. When disrupted, they can lead to severe symptoms, including paralysis and respiratory failure. Understanding this mechanism is vital for recognizing poisoning symptoms and seeking immediate medical intervention.

Acetylcholine receptors, found at neuromuscular junctions, are responsible for transmitting signals from nerves to muscles. *Amanita* mushrooms contain toxins such as α-amanitin and muscarine, which interfere with these receptors. Muscarine, for instance, overstimulates acetylcholine receptors, leading to excessive nerve firing. This results in symptoms like profuse sweating, salivation, and gastrointestinal distress within 15–30 minutes of ingestion. While muscarine poisoning is rarely fatal, it serves as an early warning sign of mushroom toxicity.

The more insidious threat comes from α-amanitin, a toxin found in *Amanita phalloides* (Death Cap) and *Amanita virosa* (Destroying Angel). Unlike muscarine, α-amanitin acts indirectly by damaging liver and kidney cells, leading to systemic failure. However, its initial effects on acetylcholine receptors cause delayed symptoms, often appearing 6–24 hours after ingestion. This latency can mislead victims into believing they are safe, only for severe dehydration, organ failure, and neurological symptoms to emerge later. Even a small cap of *Amanita phalloides* contains enough α-amanitin to be lethal, with doses as low as 0.1 mg/kg body weight proving fatal.

To mitigate the risks, immediate medical attention is critical. If ingestion is suspected, induce vomiting and administer activated charcoal to reduce toxin absorption. Hospitals may use atropine, an acetylcholine receptor antagonist, to counteract muscarine’s effects. For α-amanitin poisoning, supportive care, including liver transplants in severe cases, is often necessary. Prevention remains the best strategy—never consume wild mushrooms without expert identification, and educate children about the dangers of foraging.

In summary, *Amanita* mushrooms target acetylcholine receptors, triggering a cascade of symptoms from mild muscarinic effects to life-threatening organ failure. Recognizing early signs, understanding toxin mechanisms, and acting swiftly can save lives. This knowledge underscores the importance of caution and awareness in environments where poisonous mushrooms thrive.

Identifying Poisonous Russula Mushrooms: A Visual Guide to Their Appearance

You may want to see also

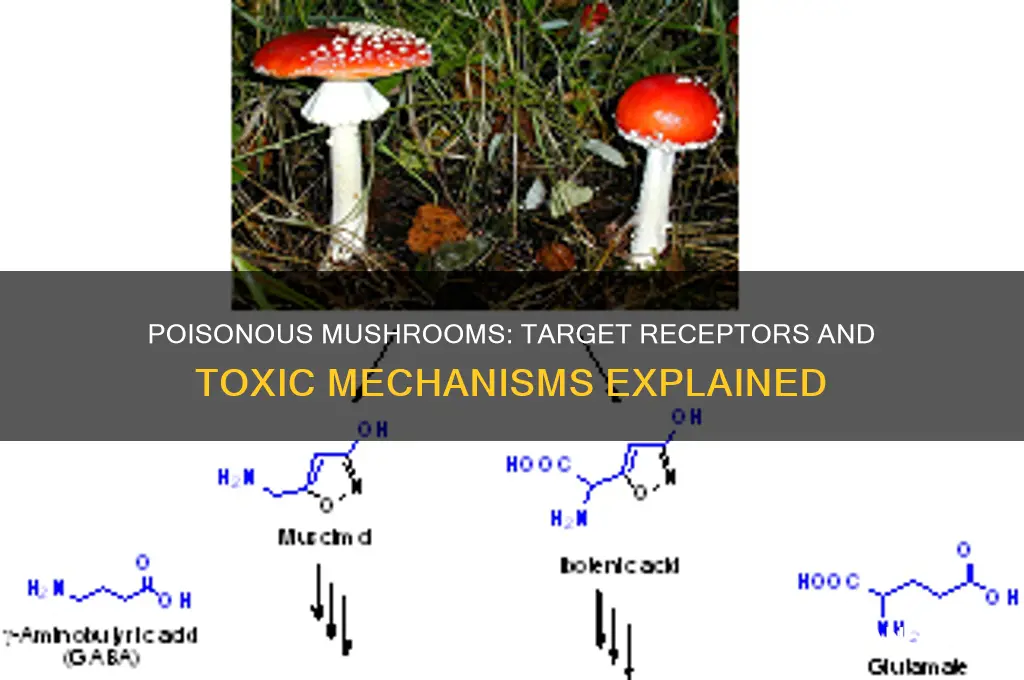

GABA Receptors: Some toxins inhibit GABA receptors, leading to seizures and neurological symptoms

Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors play a critical role in the central nervous system by inhibiting neuronal activity, effectively calming the brain and preventing overstimulation. When toxins from certain poisonous mushrooms interfere with these receptors, the inhibitory balance is disrupted, leading to a cascade of neurological symptoms. For instance, mushrooms like *Conocybe filaris* and *Pholiotina rugosa* contain compounds that act as GABA receptor antagonists, blocking the calming effects of GABA. This inhibition results in heightened neuronal firing, manifesting as seizures, muscle spasms, and confusion. Understanding this mechanism is crucial for recognizing and treating mushroom poisoning promptly.

To illustrate, consider the case of a 30-year-old hiker who ingested *Conocybe filaris*, mistaking it for a harmless species. Within 6–24 hours, they experienced agitation, visual disturbances, and eventually, tonic-clonic seizures. These symptoms align with GABA receptor inhibition, as the toxin prevents GABA from binding to its receptors, leaving the brain in a state of unchecked excitation. Treatment in such cases involves benzodiazepines, which enhance GABA activity, and supportive care to manage seizures and prevent complications. Early identification of the mushroom species and symptom onset is vital for effective intervention.

From a practical standpoint, avoiding GABA-inhibiting mushroom toxins requires awareness of high-risk species and their habitats. *Conocybe* and *Pholiotina* species, often found in grassy areas, are particularly dangerous due to their small size and resemblance to edible varieties. For foragers, the rule of thumb is to never consume wild mushrooms without expert verification. If accidental ingestion occurs, immediate medical attention is essential. Symptoms like restlessness, tremors, or confusion within 24 hours of consumption should raise suspicion of GABA receptor inhibition, warranting urgent treatment.

Comparatively, GABA receptor inhibition by mushroom toxins differs from other neurotoxic mechanisms, such as those involving muscarinic receptors. While muscarinic toxins cause excessive acetylcholine activity (e.g., sweating, salivation), GABA inhibition leads to disinhibition and hyperexcitability. This distinction highlights the importance of symptom-based diagnosis. For instance, a patient with seizures and rigidity is more likely to have GABA receptor involvement than one with profuse sweating and diarrhea. Tailoring treatment to the specific toxin mechanism improves outcomes and reduces long-term neurological damage.

In conclusion, GABA receptor inhibition by mushroom toxins is a life-threatening condition requiring swift recognition and action. By understanding the role of GABA in neuronal regulation and the effects of its inhibition, healthcare providers and foragers alike can better navigate the risks associated with poisonous mushrooms. Education, caution, and timely medical intervention remain the cornerstones of preventing severe neurological consequences from these insidious toxins.

Identifying Poisonous Mushrooms in New York State: A Safety Guide

You may want to see also

Muscarinic Receptors: Muscarine-containing mushrooms overstimulate these receptors, causing sweating and vision issues

Mushrooms containing muscarine, such as *Clitocybe dealbata* and *Inocybe* species, target muscarinic receptors in the body, leading to a distinct set of symptoms known as muscarinic syndrome. These receptors, part of the cholinergic system, are typically activated by the neurotransmitter acetylcholine and play a role in regulating functions like heart rate, sweating, and pupil constriction. When muscarine binds to these receptors, it mimics and overstimulates their natural activation, resulting in excessive sweating, blurred vision, and other autonomic responses.

Consider the mechanism: muscarinic receptors are divided into five subtypes (M1–M5), each with specific functions. Muscarine primarily acts on M1, M3, and M5 receptors, causing smooth muscle contraction, increased glandular secretion, and slowed heart rate. For instance, overstimulation of M3 receptors in sweat glands leads to profuse sweating, while activation of M3 receptors in the iris causes pupil constriction, often resulting in blurred or darkened vision. These effects are dose-dependent; ingestion of as little as 10–20 grams of muscarine-containing mushrooms can trigger symptoms in adults, though severity varies based on individual tolerance and mushroom concentration.

To manage exposure, immediate steps are critical. If ingestion is suspected, induce vomiting within 30 minutes to reduce absorption, and administer activated charcoal if available. However, avoid this in cases of altered mental status or seizures. Symptoms typically appear within 15–30 minutes to 2 hours and may include abdominal cramps, diarrhea, and bronchial secretions. Treatment focuses on atropine, an antagonist that blocks muscarinic receptors, reversing symptoms like bradycardia and bronchorrhea. Dosage is titrated to effect, starting with 0.5–2 mg intravenously in adults, repeated every 5–10 minutes until symptoms resolve.

Comparatively, muscarinic syndrome differs from other mushroom poisonings, such as those caused by amanitin-containing species, which primarily damage the liver and kidneys. While amanitin toxicity is life-threatening and requires supportive care, muscarinic syndrome is rarely fatal if treated promptly. However, misidentification of mushrooms remains a common risk; for example, *Clitocybe dealbata* is often mistaken for edible species like *Marasmius oreades*. Always verify mushroom identity using multiple field guides or consult an expert before consumption.

Practically, prevention is key. Educate foragers on the characteristics of muscarine-containing mushrooms, such as the pale gills and slender stems of *Inocybe* species. Carry a field kit with activated charcoal and contact information for poison control. If symptoms occur, monitor vital signs like heart rate and respiratory status, and seek emergency care immediately. Understanding muscarinic receptors and their interaction with muscarine not only highlights the dangers of these mushrooms but also empowers individuals to respond effectively to accidental exposure.

Is Mold on Dried Mushrooms Poisonous? Risks and Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Serotonin Receptors: Psilocybin binds to serotonin receptors, altering mood, perception, and cognition

Psilocybin, the psychoactive compound found in certain mushrooms, exerts its profound effects by binding primarily to serotonin receptors in the brain. Specifically, it has a high affinity for the 5-HT2A receptor, a subtype of serotonin receptor that plays a crucial role in mood regulation, perception, and cognition. When psilocybin is ingested, it is metabolized into psilocin, which then activates these receptors, leading to altered states of consciousness. This interaction explains why individuals often report enhanced sensory experiences, emotional introspection, and shifts in thought patterns after consuming these mushrooms.

Understanding the dosage is critical when discussing psilocybin’s effects. A typical recreational dose ranges from 1 to 3 grams of dried mushrooms, which corresponds to approximately 10 to 30 milligrams of psilocybin. At these levels, users commonly experience mild to moderate alterations in perception, mood, and cognition. However, doses above 3 grams can lead to intense, sometimes overwhelming, effects, including ego dissolution and profound spiritual experiences. It’s essential to approach higher doses with caution, ideally in a controlled setting with a trusted guide or therapist, as the experience can be unpredictable and emotionally challenging.

Comparatively, psilocybin’s interaction with serotonin receptors differs from that of poisonous mushrooms, which often target other receptors or disrupt cellular processes directly. For instance, amanita mushrooms contain amatoxins that inhibit RNA polymerase II, leading to liver and kidney failure, rather than altering neurotransmitter systems. This distinction highlights why psilocybin, while psychoactive, is not considered physiologically toxic in the same way as many poisonous mushrooms. However, its psychological effects can still pose risks, particularly for individuals with a history of mental health disorders or those unprepared for the intensity of the experience.

Practical tips for those considering psilocybin use include setting and mindset. The environment in which the experience takes place (the "set") and the individual’s mental state (the "setting") significantly influence the outcome. A calm, familiar, and safe space, coupled with a positive and open mindset, can enhance the therapeutic potential of the experience. Additionally, staying hydrated and avoiding mixing psilocybin with other substances, including alcohol, can reduce the risk of adverse reactions. For those using psilocybin for therapeutic purposes, working with a trained professional is highly recommended to maximize benefits and minimize risks.

In conclusion, psilocybin’s binding to serotonin receptors, particularly the 5-HT2A subtype, underpins its ability to alter mood, perception, and cognition. While it shares the classification of a "mushroom" with poisonous varieties, its mechanism of action and effects are distinct. By understanding dosage, comparing its action to other mushrooms, and following practical guidelines, individuals can approach psilocybin use with greater awareness and safety. This knowledge is particularly valuable as research into its therapeutic applications continues to expand, offering new possibilities for mental health treatment.

Are Armillaria Mushrooms Poisonous? Unveiling the Truth About Honey Fungi

You may want to see also

Ryanodine Receptors: Amatoxins disrupt calcium regulation via ryanodine receptors, causing liver and kidney damage

Amatoxins, a group of cyclic octapeptides found in certain poisonous mushrooms like *Amanita phalloides* (the death cap), exert their lethal effects by targeting ryanodine receptors (RyRs), crucial proteins involved in calcium regulation within cells. These receptors, primarily located in the endoplasmic reticulum of muscle and liver cells, act as calcium release channels, maintaining intracellular calcium homeostasis. When amatoxins bind to RyRs, they disrupt this delicate balance, leading to uncontrolled calcium release and subsequent cellular damage. This mechanism underscores the severity of amatoxin poisoning, which often results in acute liver and kidney failure if left untreated.

The interaction between amatoxins and RyRs is both rapid and insidious. Within hours of ingestion, amatoxins are absorbed into the bloodstream and transported to the liver, where they accumulate and bind irreversibly to RyRs. This binding triggers a cascade of events: calcium ions flood the cytoplasm, impairing cellular functions and inducing apoptosis. The liver, being the primary site of toxin metabolism, bears the brunt of this damage, leading to symptoms like jaundice, coagulopathy, and hepatic encephalopathy. Kidney damage follows as a secondary effect, often due to hypovolemia and toxin-induced nephrotoxicity. Early intervention, including gastric decontamination, activated charcoal administration, and supportive care, is critical to mitigate these effects.

Understanding the role of RyRs in amatoxin toxicity highlights the importance of calcium regulation in cellular health. Normally, RyRs open transiently to release calcium ions, which act as second messengers in signaling pathways. Amatoxins, however, force these channels into a permanently open state, depleting calcium stores in the endoplasmic reticulum and overwhelming the cell’s ability to maintain homeostasis. This disruption is particularly devastating in hepatocytes, where calcium dysregulation triggers oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction, accelerating cell death. For clinicians, recognizing this mechanism can guide treatment strategies, such as the use of N-acetylcysteine to counteract oxidative damage and continuous venovenous hemofiltration to remove circulating toxins.

A comparative analysis of amatoxin poisoning versus other mushroom toxins reveals the unique danger posed by RyR disruption. Unlike orellanine, which directly damages renal tubules, or ibotenic acid, which acts on glutamate receptors in the brain, amatoxins target a fundamental cellular process with systemic consequences. This specificity makes amatoxin poisoning particularly challenging to treat, as the damage progresses silently during the initial asymptomatic phase (6–24 hours post-ingestion). Public education is key to prevention, emphasizing the importance of accurate mushroom identification and avoiding consumption of wild mushrooms without expert verification. Even small doses (as little as 0.1 mg/kg of amatoxins) can be fatal, particularly in children, underscoring the need for vigilance.

In conclusion, the interaction between amatoxins and ryanodine receptors exemplifies the intricate relationship between toxins and cellular machinery. By disrupting calcium regulation, amatoxins unleash a chain reaction of cellular damage that culminates in organ failure. This knowledge not only informs clinical management but also underscores the broader implications of toxin-receptor interactions in toxicology. For foragers, chefs, and the general public, awareness of this mechanism serves as a stark reminder of the potential dangers lurking in seemingly innocuous fungi. When in doubt, seek expert advice—a simple precaution that could save lives.

Are Mushrooms Poisonous to Cows? Understanding Risks and Safety

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Poisonous mushrooms often target acetylcholine receptors, particularly those in the nervous system, leading to symptoms like muscle paralysis, seizures, or respiratory failure.

Yes, some poisonous mushrooms, like those containing psilocybin or similar compounds, can interact with serotonin receptors in the brain, causing hallucinations or altered mental states.

Certain toxic mushrooms, such as those containing amatoxins, indirectly affect GABA receptors by causing liver damage, which disrupts normal neurological function and can lead to coma or death.

While rare, some mushrooms contain compounds that may interact with opioid receptors, though this is less common compared to their effects on acetylcholine or serotonin receptors.