The death cap mushroom, scientifically known as *Amanita phalloides*, is a highly toxic and potentially lethal fungus primarily found in Europe, particularly in regions with temperate climates such as the United Kingdom, France, and Germany. However, due to the accidental introduction of this species through imported trees and soil, death caps have also established themselves in other parts of the world, including North America, Australia, and New Zealand. They thrive in deciduous and coniferous forests, often forming symbiotic relationships with trees like oaks, beeches, and pines. Their presence is especially notable in areas with mild, wet weather, making them a significant concern for foragers and mushroom enthusiasts who must exercise extreme caution to avoid misidentifying them as edible species.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Scientific Name | Amanita phalloides |

| Common Name | Death Cap |

| Geographic Distribution | Europe, North America, Australia, Asia (introduced) |

| Native Region | Europe |

| Habitat | Mycorrhizal with broadleaf trees (e.g., oak, beech, chestnut) |

| Soil Preference | Calcium-rich, alkaline soils |

| Climate | Temperate regions |

| Season | Summer to early autumn |

| Spread | Introduced to new regions via soil, plant material, or human activity |

| Notable Regions | - Europe: Widespread - North America: West Coast (California, Oregon), East Coast (introduced) - Australia: Southeastern regions - Asia: Introduced in some areas |

| Invasive Status | Invasive in non-native regions |

| Toxicity | Highly toxic, often fatal if ingested |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Europe: Widespread in Europe, often found in deciduous and mixed forests, especially under oak and beech trees

- North America: Common in California, Oregon, and the Pacific Northwest, thriving in coastal woodland areas

- Australia: Introduced species, frequently found in urban gardens, parks, and eucalyptus forests across the continent

- Asia: Native to parts of Asia, particularly in China and Japan, growing in temperate forests

- New Zealand: Found in both native and introduced forests, often associated with pine plantations and urban areas

Europe: Widespread in Europe, often found in deciduous and mixed forests, especially under oak and beech trees

The death cap mushroom, *Amanita phalloides*, thrives across Europe, particularly in deciduous and mixed forests. Its preference for oak and beech trees is well-documented, making these areas prime hunting grounds for foragers—and a critical zone for caution. Unlike some fungi that favor specific microclimates, the death cap’s adaptability allows it to flourish in diverse European ecosystems, from the damp woodlands of the UK to the temperate forests of Central Europe. This widespread presence underscores the importance of accurate identification, as mistaking it for edible species like the straw mushroom or Caesar’s mushroom can be fatal.

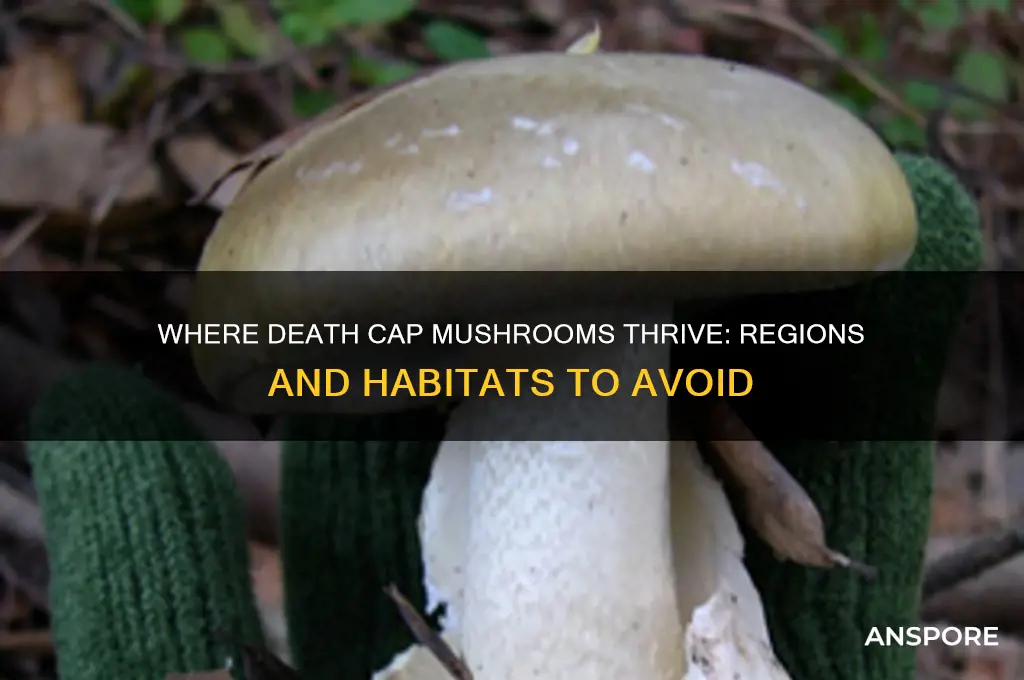

Foraging in European forests requires a methodical approach. Begin by familiarizing yourself with the death cap’s distinctive features: a pale green to yellowish cap, white gills, and a bulbous base often encased in a cup-like volva. Carry a reliable field guide or use a mushroom identification app, but never rely solely on digital tools. Always cross-reference findings with multiple sources. If you’re unsure, err on the side of caution—consuming even a small portion of a death cap can lead to severe liver and kidney damage within 6–24 hours. Symptoms like nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea may initially seem benign but can rapidly escalate to organ failure.

Comparing the death cap to its edible look-alikes highlights the danger of superficial similarities. For instance, the edible paddy straw mushroom (*Volvariella volvacea*) also has a volva, but its cap is grayish-brown and its gills pinkish. The death cap’s waxy texture and persistent volva are key differentiators. A practical tip: avoid picking any mushrooms with a volva unless you’re absolutely certain of their identity. Even experienced foragers have fallen victim to the death cap’s deceptive appearance, emphasizing the need for vigilance.

To minimize risk, focus on foraging in areas less likely to harbor death caps. Coniferous forests, for example, are less hospitable to this species. If you’re in a deciduous or mixed forest, particularly one dominated by oak or beech, assume the death cap is present and proceed with extreme caution. Teach children and pets to avoid touching or ingesting wild mushrooms, as the death cap’s toxins can be absorbed through the skin or ingested indirectly. Finally, if you suspect poisoning, seek medical attention immediately—time is critical, and early treatment with activated charcoal or liver transplants can be life-saving.

In conclusion, Europe’s deciduous and mixed forests, especially those with oak and beech trees, are both a haven for biodiversity and a potential minefield for foragers. The death cap’s prevalence in these regions demands respect and preparation. By combining knowledge, caution, and practical strategies, you can safely enjoy the bounty of European woodlands while avoiding the deadly pitfalls.

Discover Hawaii's Hidden Magic Mushroom Spots: A Forager's Guide

You may want to see also

North America: Common in California, Oregon, and the Pacific Northwest, thriving in coastal woodland areas

The death cap mushroom, *Amanita phalloides*, is a silent predator lurking in the lush, coastal woodlands of North America, particularly in California, Oregon, and the Pacific Northwest. These regions provide the ideal environment for this deadly fungus, characterized by mild, humid climates and an abundance of oak, pine, and fir trees. Foragers and hikers must remain vigilant, as the death cap’s innocuous appearance—often white to greenish, with a smooth cap—belies its lethal toxicity. A single mushroom contains enough amatoxins to cause severe liver and kidney failure in humans, with symptoms appearing 6–24 hours after ingestion.

To avoid accidental poisoning, familiarize yourself with the death cap’s key features: a bulbous base, white gills, and a skirt-like ring on the stem. However, positive identification requires expertise, so the safest rule is to avoid consuming any wild mushrooms without professional guidance. In these regions, death caps often appear in the same locations year after year, particularly after autumn rains. If you suspect ingestion, seek immediate medical attention; early treatment with activated charcoal and supportive care can be life-saving.

Comparatively, the death cap’s prevalence in these areas contrasts with its rarity in drier, inland regions of North America. The coastal climate mimics its native European habitat, where it has caused countless fatalities. This geographic specificity underscores the importance of regional awareness: while death caps thrive in the Pacific Northwest, they are virtually absent in states like Arizona or Nevada. Foraging enthusiasts in California and Oregon should prioritize education, attending workshops or consulting mycological societies to distinguish death caps from edible lookalikes like the paddy straw mushroom.

Descriptively, the coastal woodlands where death caps flourish are as enchanting as they are dangerous. Towering evergreens, dappled sunlight, and the scent of damp earth create a serene backdrop for this hidden menace. The mushroom’s symbiotic relationship with tree roots allows it to thrive in these ecosystems, often appearing in clusters near oak or chestnut trees. While the landscape invites exploration, it demands respect. Always carry a field guide, avoid touching unknown fungi, and teach children to admire mushrooms from a distance.

Persuasively, the death cap’s presence in these regions should not deter outdoor enthusiasts but rather encourage informed curiosity. The Pacific Northwest’s natural beauty is unparalleled, and with proper precautions, its woodlands remain safe for all. Schools, community centers, and parks should offer educational programs on mushroom safety, particularly targeting families and new foragers. By fostering awareness, we can coexist with this deadly fungus, appreciating its ecological role without falling victim to its toxicity. Remember: in the wild, caution is the best companion.

Discover Alaska's Sulfur Shelf Mushrooms: Prime Foraging Spots Revealed

You may want to see also

Australia: Introduced species, frequently found in urban gardens, parks, and eucalyptus forests across the continent

The death cap mushroom, *Amanita phalloides*, is a silent invader in Australia’s urban and natural landscapes. Originally from Europe, this toxic fungus has established itself in gardens, parks, and eucalyptus forests across the continent, often hitchhiking on introduced tree species like oaks and chestnuts. Its presence is no mere curiosity—it’s a lethal threat, responsible for the majority of fatal mushroom poisonings worldwide. In Australia, cases of ingestion have risen as the fungus thrives in temperate regions, particularly in Victoria, South Australia, and Tasmania, where it forms symbiotic relationships with non-native trees.

To identify this menace, look for a pale green to yellowish cap, often 5–15 cm wide, with white gills and a bulbous base. It resembles edible species like the straw mushroom, a dangerous similarity that lures foragers into a fatal mistake. Symptoms of poisoning—nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and liver failure—appear 6–24 hours after ingestion, with a mere 50 grams enough to kill an adult. Children are especially vulnerable, as the mushroom’s attractive appearance can tempt curious hands.

Prevention is straightforward but critical. Avoid foraging in areas where death caps are known to grow, particularly under introduced deciduous trees in urban settings. If you suspect ingestion, seek medical attention immediately—time is of the essence. Hospitals may administer activated charcoal to reduce toxin absorption, followed by supportive care or, in severe cases, a liver transplant. Public awareness campaigns in affected regions have reduced accidental poisonings, but vigilance remains key.

Comparatively, Australia’s native fungi are far less dangerous, with only a handful of toxic species. The death cap’s success as an introduced species highlights the unintended consequences of human activity, from landscaping choices to global trade. Its spread mirrors that of other invasive species, like the cane toad, but with a more insidious, less visible impact. Eradication is nearly impossible, as spores persist in soil for years, making coexistence—and caution—the only viable strategy.

For gardeners and park managers, proactive measures can limit the fungus’s spread. Avoid planting oak and chestnut trees in public spaces, and regularly inspect areas where they already exist. Community education programs, particularly in schools, can teach children and adults alike to recognize and avoid the death cap. While its presence is a stark reminder of ecological disruption, it also underscores the importance of informed stewardship in a changing environment.

Discovering Rare Mushrooms: KH Final Mix Secrets and Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Asia: Native to parts of Asia, particularly in China and Japan, growing in temperate forests

The death cap mushroom, *Amanita phalloides*, is a notorious toxin lurking in the temperate forests of Asia, particularly in China and Japan. Its presence in these regions is not merely a coincidence but a result of specific ecological conditions that favor its growth. These mushrooms thrive in symbiotic relationships with deciduous and coniferous trees, often found in areas with mild, humid climates. For foragers and nature enthusiasts, understanding this habitat is crucial, as misidentification can lead to severe poisoning or even death.

To safely navigate these forests, one must recognize the death cap’s distinctive features: a pale green to yellowish cap, white gills, and a bulbous base often surrounded by a cup-like volva. However, relying solely on visual cues is risky, as they resemble edible species like the paddy straw mushroom. A practical tip for those exploring these regions is to carry a field guide or use a reliable mushroom identification app. Additionally, avoid consuming wild mushrooms without expert verification, especially in areas where death caps are endemic.

Comparatively, the prevalence of death caps in Asia versus Europe highlights the role of mycorrhizal associations in their distribution. In China and Japan, these mushrooms often accompany oak, beech, and pine trees, mirroring their European habitats. However, Asia’s diverse temperate ecosystems provide unique niches, such as the forests of Hokkaido in Japan or the mountainous regions of southwestern China, where they flourish. This regional specificity underscores the importance of localized knowledge in mushroom foraging.

For those living in or visiting these areas, awareness is key. Educate children and pets about the dangers of wild mushrooms, as even a small bite of a death cap can be fatal. If ingestion is suspected, immediate medical attention is critical. Hospitals in endemic regions like China and Japan are often equipped to treat amatoxin poisoning, but time is of the essence. Carrying activated charcoal or knowing the location of the nearest healthcare facility can be lifesaving.

In conclusion, while the temperate forests of Asia, particularly in China and Japan, offer breathtaking biodiversity, they also harbor the deadly *Amanita phalloides*. By understanding its habitat, recognizing its features, and adopting cautious practices, one can appreciate these ecosystems without falling victim to their most notorious resident. Knowledge and vigilance are the best defenses against the death cap’s silent threat.

Discovering Morel Mushrooms: Top Spots in McCall, Idaho

You may want to see also

New Zealand: Found in both native and introduced forests, often associated with pine plantations and urban areas

The death cap mushroom, *Amanita phalloides*, is a silent killer lurking in unexpected places, and New Zealand’s diverse landscapes are no exception. Unlike regions where death caps are tied to specific ecosystems, New Zealand’s distribution is strikingly versatile. Here, these toxic fungi thrive in both native forests, where they form symbiotic relationships with indigenous trees, and introduced forests, particularly pine plantations. This dual habitat preference makes them a unique threat, as they exploit both ancient and modern ecosystems. Urban areas, too, are not immune—death caps often appear in city parks, gardens, and even along roadside plantings, where soil disturbance and imported tree species create ideal conditions. This adaptability underscores the need for vigilance across varied environments.

For those exploring New Zealand’s forests, whether native or planted, awareness is key. Pine plantations, a staple of the country’s timber industry, are particularly high-risk zones. Death caps here often grow in clusters at the base of trees, their greenish-white caps blending deceptively with the forest floor. In native forests, they may appear near beech or oak trees, their mycorrhizal associations mirroring those in their European origins. Urban dwellers are not exempt—check gardens with oak, chestnut, or pine trees, especially after rain, as moisture triggers fruiting. A single death cap contains enough amatoxins to cause severe liver and kidney failure in humans, with symptoms appearing 6–24 hours after ingestion. Children are especially vulnerable, as even a small bite can be fatal.

To mitigate risk, follow these practical steps: avoid picking wild mushrooms for consumption unless you’re an expert, teach children to “look but don’t touch,” and carry a field guide or use a mushroom identification app when hiking. If you suspect poisoning, seek medical attention immediately—early treatment with activated charcoal or silibinin can be life-saving. For gardeners, consider removing pine cones or acorns to discourage spore growth, though this is not foolproof. Lastly, report sightings to local authorities or mycological societies to aid in tracking their spread.

New Zealand’s death cap problem is a cautionary tale of ecological interconnectedness. Introduced species, whether trees or fungi, can disrupt ecosystems in unforeseen ways. The death cap’s presence in both native and introduced forests highlights the need for holistic environmental management. While eradication is unlikely, public education and proactive measures can reduce the risk. For foragers, hikers, and urbanites alike, the message is clear: admire these fungi from afar, for their beauty belies a deadly nature.

Exploring Nature's Hidden Gems: Locating Hallucinogenic Magic Mushrooms Safely

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Death cap mushrooms (*Amanita phalloides*) are commonly found in Europe, particularly in regions with temperate climates such as the United Kingdom, France, and Germany.

While death cap mushrooms are not native to North America, they have been introduced and can now be found in regions like the West Coast (California, Oregon, Washington) and the East Coast (e.g., New York, Massachusetts) due to the spread of their spores through imported trees and plants.

Death cap mushrooms are not typically found in tropical or arid regions. They prefer temperate climates with mild, moist environments, often growing in association with trees like oaks, beeches, and pines.