The chaga mushroom, scientifically known as *Inonotus obliquus*, is a unique and highly sought-after fungus that primarily grows on birch trees (*Betula* species). This symbiotic relationship is crucial, as the chaga draws nutrients from the birch while potentially aiding the tree in resisting pathogens. Found predominantly in cold northern climates, such as those in Siberia, Canada, and the northern United States, chaga appears as a dark, charcoal-like growth on the bark of mature birch trees. Its distinct appearance and medicinal properties have made it a staple in traditional and modern herbal remedies, though its reliance on birch trees underscores the importance of sustainable harvesting practices to preserve both the mushroom and its host.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Tree Species | Primarily Birch (Betula spp.), especially Paper Birch (Betula papyrifera) and Yellow Birch (Betula alleghaniensis) |

| Geographic Range | Northern Hemisphere, including North America, Europe, Asia, and Russia |

| Preferred Habitat | Cold, temperate forests with well-drained, acidic soil |

| Tree Age | Typically grows on mature birch trees, often over 40 years old |

| Tree Health | Commonly found on weakened, injured, or dying birch trees |

| Growth Location | Usually grows on the trunk, often on the north side of the tree |

| Symbiotic Relationship | Parasitic to the tree, eventually contributing to its decline |

| Additional Hosts | Rarely found on other hardwood trees like beech, alder, or maple, but birch is the primary host |

| Climate | Thrives in cold climates with distinct seasons, including freezing winters |

| Soil Conditions | Prefers acidic, nutrient-poor soil typical of boreal forests |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Birch trees: Chaga primarily grows on birch, forming a symbiotic relationship with the host tree

- Geographic distribution: Found on birch in cold climates like Siberia, Canada, and Northern Europe

- Tree age and health: Chaga prefers older, weakened birch trees for optimal growth conditions

- Bark characteristics: Birch bark’s high betulin content is essential for Chaga’s development

- Alternative hosts: Rarely, Chaga grows on alder, beech, or oak, but birch is most common

Birch trees: Chaga primarily grows on birch, forming a symbiotic relationship with the host tree

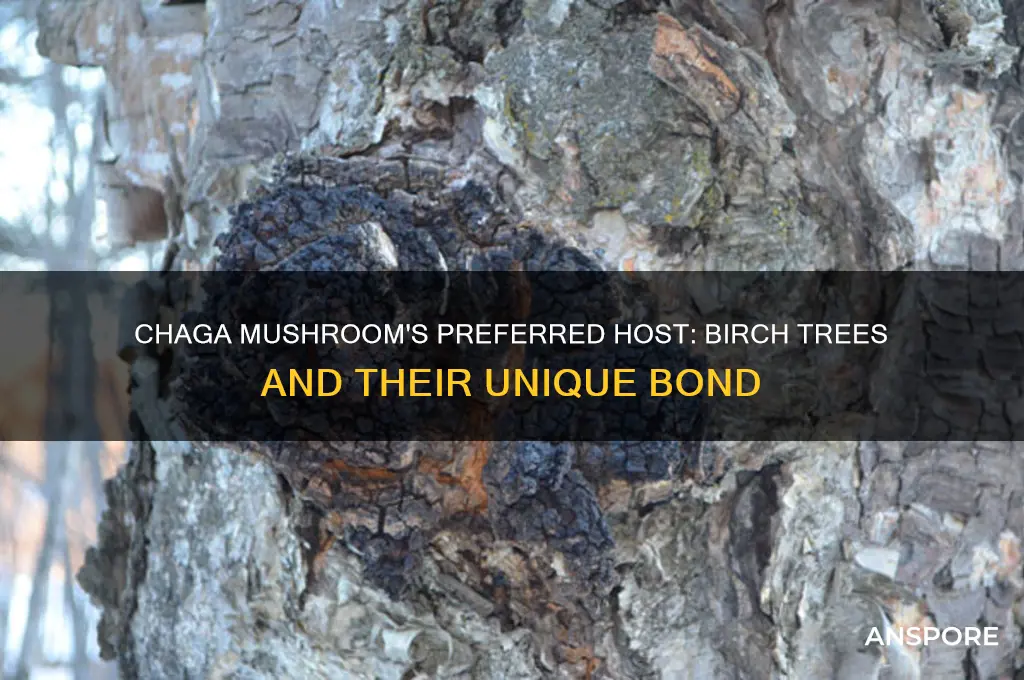

Chaga mushrooms, scientifically known as *Inonotus obliquus*, have a unique and specific relationship with birch trees (*Betula* species). This parasitic fungus primarily grows on birch trees, forming a distinctive black, charcoal-like mass known as a conk or sclerotium. The relationship between chaga and birch is not merely coincidental but deeply symbiotic, with both organisms influencing each other’s growth and survival. Birch trees provide the essential nutrients and environment chaga needs to thrive, while the fungus, in turn, plays a role in the tree’s nutrient cycling and ecosystem dynamics.

The birch tree’s bark is particularly conducive to chaga’s growth due to its high levels of betulin, a compound that the fungus metabolizes for energy. Chaga begins its life cycle as a microscopic spore that lands on a birch tree, often entering through a wound or weak spot in the bark. Over time, it colonizes the tree’s inner layers, drawing nutrients from the sapwood while slowly breaking down the tree’s structural integrity. This process can take several years, during which the chaga conk grows larger, becoming a visible and harvestable entity. Despite its parasitic nature, chaga does not typically kill the birch tree outright; instead, it often weakens the tree over time, creating a delicate balance between the two organisms.

The symbiotic relationship between chaga and birch is further highlighted by the fungus’s role in the tree’s ecosystem. As chaga grows, it helps the birch tree by breaking down complex organic compounds into simpler forms, which can then be recycled back into the soil. This process enriches the surrounding environment, benefiting other plants and microorganisms. Additionally, chaga’s presence can indicate the health of the birch tree and its environment, as the fungus thrives in mature, nutrient-rich forests where birch trees are abundant.

Harvesting chaga from birch trees requires careful consideration to maintain this symbiotic balance. Sustainable practices involve taking only a portion of the conk and ensuring the tree’s overall health is not compromised. Overharvesting can weaken the birch tree further, disrupting the ecosystem and reducing the availability of chaga in the long term. Thus, understanding and respecting the relationship between chaga and birch is crucial for both conservation and the continued use of this valuable fungus.

In summary, birch trees are the primary hosts for chaga mushrooms, providing the necessary nutrients and environment for the fungus to grow. This symbiotic relationship is characterized by chaga’s reliance on birch for betulin and the tree’s indirect benefit from the fungus’s role in nutrient cycling. By focusing on sustainable harvesting practices, we can preserve this unique bond and ensure the longevity of both chaga and birch in their natural habitats.

Turkey Tail Mushrooms in the UK: Habitat and Growth Insights

You may want to see also

Geographic distribution: Found on birch in cold climates like Siberia, Canada, and Northern Europe

The chaga mushroom, scientifically known as *Inonotus obliquus*, has a distinct geographic distribution closely tied to its preferred host tree, the birch (*Betula* species). This parasitic fungus thrives in cold climates, where birch trees are abundant. One of the most well-known regions for chaga growth is Siberia, a vast expanse of Russia characterized by its harsh, frigid winters and dense birch forests. Here, chaga mushrooms form black, charcoal-like conks on the trunks of birch trees, often growing undisturbed for many years due to the region's low human population density and pristine wilderness.

In Canada, chaga is commonly found in the boreal forests that stretch across the country's northern regions, particularly in provinces like Quebec, Ontario, and the Prairie Provinces. These areas share similar climatic conditions with Siberia, featuring long, cold winters and short summers, which are ideal for chaga's growth. Canadian birch trees, especially the paper birch (*Betula papyrifera*), provide a suitable substrate for the mushroom, making it a valuable resource for both local communities and commercial harvesters.

Northern Europe is another significant region where chaga mushrooms grow on birch trees. Countries such as Finland, Sweden, Norway, and parts of the Baltic states have extensive birch forests that support chaga populations. The cold, temperate climate of these regions, combined with the prevalence of birch trees, creates an optimal environment for the fungus. In these areas, chaga has been traditionally harvested for its medicinal properties, deeply rooted in local folklore and natural remedies.

While chaga is primarily associated with birch trees in cold climates, it is important to note that its distribution is not limited to these regions alone. However, the combination of birch trees and cold temperatures remains the most critical factor for its growth. The birch tree's unique chemistry and the cold climate's stress on the tree are believed to enhance the concentration of beneficial compounds in the chaga mushroom, making these geographic areas particularly prized for high-quality chaga.

For those seeking to identify or harvest chaga, understanding its geographic distribution is key. Look for mature birch trees in forests of Siberia, Canada, or Northern Europe, particularly in areas with cold, continental climates. The mushroom typically appears as a black, crusty growth on the tree's trunk, often on the north side where it receives less sunlight. This specific habitat requirement underscores the intimate relationship between chaga, birch trees, and cold climates, making it a fascinating example of nature's adaptability.

Mastering Mushroom Cultivation: A Beginner's Guide to Growing Edible Fungi

You may want to see also

Tree age and health: Chaga prefers older, weakened birch trees for optimal growth conditions

Chaga mushrooms (Inonotus obliquus) have a unique and specific relationship with their host trees, particularly birch trees (Betula spp.). Among the various birch species, Chaga predominantly grows on older, weakened trees, which provide the ideal conditions for its development. This preference is not coincidental but rooted in the biological needs of the mushroom and the physiological state of the tree. Older birch trees, typically those over 40 years old, have had sufficient time to accumulate the nutrients and structural characteristics that Chaga requires to thrive. Their bark becomes thicker and more textured, offering a stable substrate for the mushroom to attach and grow.

The health of the birch tree plays a critical role in Chaga’s growth dynamics. While Chaga is not inherently parasitic, it does benefit from trees that are in a state of decline. Weakened birch trees, often stressed by factors like disease, insect damage, or environmental pressures, have defense mechanisms that are less robust. This allows Chaga to establish itself more easily within the tree’s tissues. The mushroom forms a sclerotium, a hard, woody mass that draws nutrients from the tree, further contributing to the tree’s weakened state over time. This symbiotic yet slightly antagonistic relationship highlights why Chaga is rarely found on young, healthy birch trees.

The age of the birch tree also influences its bark composition, which is crucial for Chaga’s growth. Older trees develop deeper layers of lignin and other complex compounds in their bark, which Chaga utilizes for its metabolic processes. These compounds are less abundant in younger trees, making them less suitable hosts. Additionally, the bark of older trees often has cracks and crevices, providing entry points for Chaga’s mycelium to penetrate and establish a foothold. This physical characteristic is less common in younger, smoother-barked trees, further explaining Chaga’s preference for maturity.

Environmental factors also contribute to why Chaga favors older, weakened birch trees. In colder climates, where birch trees are prevalent, older trees are more susceptible to stress from harsh weather conditions, making them ideal hosts. The slow growth rate of Chaga, which can take several years to mature, aligns with the longevity of older trees. Younger trees, with their faster metabolic rates and stronger defenses, are less likely to support the prolonged development of the mushroom. Thus, the age and health of the birch tree are intertwined with Chaga’s life cycle, creating a niche habitat that is both specific and essential for its survival.

For foragers and cultivators, understanding this relationship is vital. Identifying older, weakened birch trees in forests increases the likelihood of finding Chaga. However, it is important to approach harvesting sustainably, as over-collection can further stress already vulnerable trees. Observing the tree’s overall health, such as signs of decay or insect damage, can serve as indicators of potential Chaga growth. This knowledge not only aids in locating the mushroom but also fosters a deeper appreciation for the intricate ecological interactions between Chaga and its birch hosts.

Can Mushrooms Thrive in Marl Soil? Exploring Fungal Growth Conditions

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Bark characteristics: Birch bark’s high betulin content is essential for Chaga’s development

The chaga mushroom (*Inonotus obliquus*) is a unique fungus that primarily grows on birch trees (*Betula* species), forming a distinctive black, charcoal-like mass known as a conk. This symbiotic relationship is not coincidental; the birch tree’s bark plays a critical role in chaga’s development, particularly due to its high betulin content. Betulin, a triterpene found in the outer bark of birch trees, is a key nutrient source for the chaga mushroom. Without this compound, chaga cannot thrive, making birch trees its preferred and nearly exclusive host. This specificity highlights the importance of bark characteristics in fostering chaga’s growth.

Birch bark is uniquely suited to support chaga’s development due to its chemical composition, with betulin being the most significant factor. Betulin acts as a natural defense mechanism for the birch tree, protecting it from pathogens and environmental stressors. However, chaga has evolved to utilize this compound for its own growth, breaking it down into bioactive substances that contribute to the mushroom’s medicinal properties. The high betulin content in birch bark not only attracts chaga but also provides the essential nutrients it needs to develop its characteristic conk structure. This interdependence underscores the critical role of birch bark in chaga’s life cycle.

The structure of birch bark further facilitates chaga’s growth. Birch bark consists of multiple layers, including an outer layer rich in betulin and a fibrous inner layer that provides structural support. Chaga initially colonizes the outer bark, where it can access betulin directly. Over time, the fungus penetrates deeper into the tree, forming a hardened conk that draws nutrients from the inner bark layers. This process is slow, often taking several years, but it is made possible by the birch bark’s unique composition and accessibility to betulin. Without the layered structure of birch bark, chaga would struggle to establish itself and grow.

Another critical aspect of birch bark is its resilience and adaptability to cold climates, which aligns with chaga’s preference for harsh, northern environments. Birch trees thrive in regions with cold winters and short growing seasons, conditions that also favor chaga’s slow, steady growth. The bark’s ability to withstand freezing temperatures and protect the tree from extreme weather ensures a stable environment for chaga to develop. This shared adaptability to cold climates further cements the birch tree as the ideal host for chaga, as other tree species lack the necessary bark characteristics and environmental tolerance.

In summary, the bark characteristics of birch trees, particularly their high betulin content, are essential for chaga’s development. Betulin serves as a vital nutrient source, while the bark’s layered structure and resilience to cold climates provide the ideal environment for chaga to grow. This symbiotic relationship between birch and chaga is a fascinating example of nature’s specificity, where the unique properties of birch bark enable the growth of one of the most sought-after medicinal mushrooms in the world. Understanding these bark characteristics not only explains why chaga grows on birch trees but also highlights the importance of preserving these trees for sustainable chaga harvesting.

Clear Bins for Mushroom Growing: Are They Necessary or Optional?

You may want to see also

Alternative hosts: Rarely, Chaga grows on alder, beech, or oak, but birch is most common

The Chaga mushroom, scientifically known as *Inonotus obliquus*, is most famously associated with birch trees, particularly the paper birch (*Betula papyrifera*) and other birch species. This symbiotic relationship is so prevalent that Chaga is often referred to as the "birch mushroom." The birch tree provides the ideal environment for Chaga to thrive, offering the right combination of nutrients and conditions for its growth. However, while birch is the primary and most common host, Chaga is not exclusively limited to this tree. Alternative hosts: Rarely, Chaga grows on alder, beech, or oak, but birch is most common. This rarity is due to the specific requirements Chaga has for its host tree, which birch trees fulfill more consistently than others.

When Chaga does appear on alternative hosts like alder, beech, or oak, it is often a result of unique environmental conditions or the absence of birch trees in the area. Alder trees, for instance, share some similarities with birch in terms of bark composition and habitat, which may occasionally allow Chaga to establish itself. However, alder-grown Chaga is significantly less common and often differs in appearance and quality compared to birch-grown varieties. Beech and oak trees, while less compatible, have also been documented as rare hosts, though these instances are even more uncommon and typically occur in specific geographic regions.

The preference for birch trees is rooted in the Chaga mushroom's biological needs. Birch bark contains high levels of betulin and betulinic acid, compounds that Chaga utilizes for its growth and medicinal properties. These substances are less abundant or absent in the bark of alder, beech, or oak, making these trees less suitable hosts. Additionally, birch trees' ability to withstand harsh climates, such as those in northern latitudes, aligns with Chaga's own resilience, further solidifying their symbiotic relationship.

For foragers and enthusiasts seeking Chaga, understanding its host preferences is crucial. While it is theoretically possible to find Chaga on alder, beech, or oak, the vast majority of successful harvests come from birch trees. This knowledge not only aids in efficient foraging but also highlights the importance of preserving birch forests, which are essential for Chaga's survival. Alternative hosts: Rarely, Chaga grows on alder, beech, or oak, but birch is most common, and this rarity underscores the mushroom's unique bond with birch trees.

In conclusion, while Chaga's growth on alder, beech, or oak is a fascinating biological exception, birch remains the undisputed primary host. This distinction is vital for both ecological understanding and practical applications, such as sustainable harvesting and cultivation efforts. Alternative hosts: Rarely, Chaga grows on alder, beech, or oak, but birch is most common, a fact that continues to guide research and appreciation of this remarkable mushroom.

Is Growing Mushrooms Cost-Effective? A Comprehensive Analysis for Beginners

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The chaga mushroom (Inonotus obliquus) primarily grows on birch trees, particularly the paper birch (Betula papyrifera) and other birch species.

While birch trees are the most common host, chaga has been rarely found on other hardwood trees like beech or alder, though its growth is most robust and preferred on birch.

Chaga thrives on birch trees due to their high levels of betulin, a compound the mushroom uses for growth and which contributes to its medicinal properties.

Yes, chaga is a parasitic fungus that extracts nutrients from the birch tree, eventually weakening and potentially killing the tree over time.