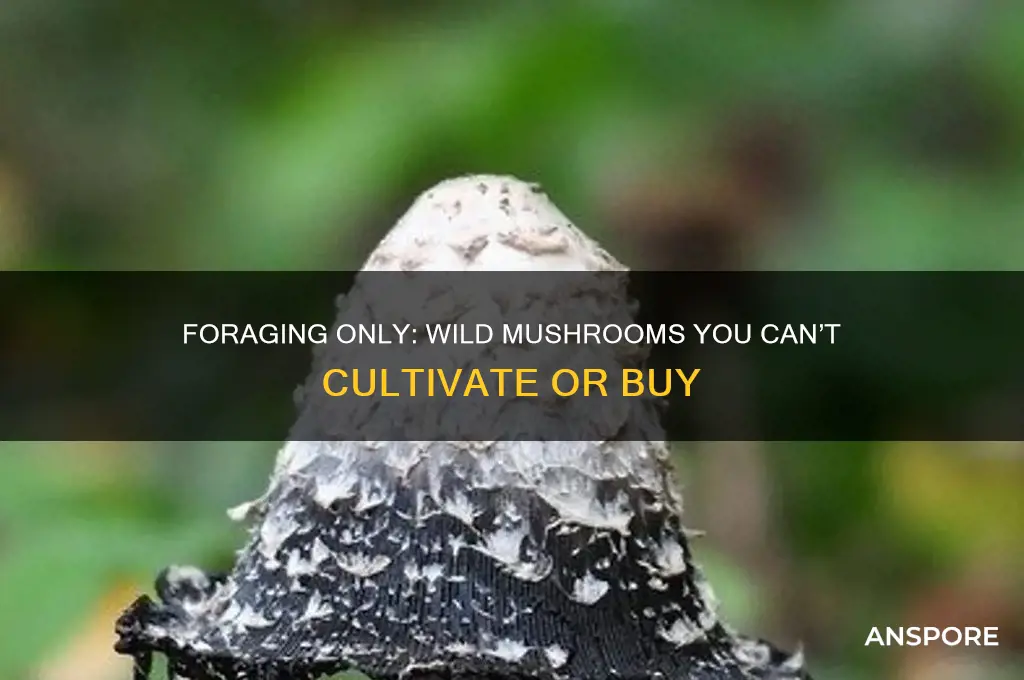

Foraging for mushrooms is a captivating yet intricate activity, as many species are not cultivated and can only be found in the wild. These elusive mushrooms, often referred to as wild-only varieties, thrive in specific ecosystems, such as forests, meadows, or decaying wood, and are highly dependent on their natural habitats. Examples include the prized Chanterelles, Porcini, and Morels, which are celebrated for their unique flavors and textures but cannot be commercially grown due to their complex symbiotic relationships with trees or specific soil conditions. Foraging for these mushrooms requires knowledge, skill, and respect for nature, as misidentification can lead to toxic or even deadly consequences. This makes the pursuit of wild mushrooms both a rewarding culinary adventure and a testament to the delicate balance of the natural world.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Rare Morel Varieties: Certain morels, like the half-free morel, grow wild, resisting cultivation

- Chanterelles in Forests: Golden chanterelles thrive in woodlands, never farmed, always foraged

- Truffle Hunting: Elusive truffles depend on specific trees and soil, impossible to cultivate

- Lion’s Mane in Nature: This shaggy mushroom grows on decaying trees, not in farms

- Porcini in the Wild: Found only in forests, porcini mushrooms cannot be commercially grown

Rare Morel Varieties: Certain morels, like the half-free morel, grow wild, resisting cultivation

The half-free morel (*Morchella populiphila*) is a forager’s prize, elusive and uncultivable. Unlike button mushrooms or shiitakes, which thrive in controlled environments, this morel insists on its wild origins. It forms symbiotic relationships with specific trees, particularly cottonwoods and aspens, and its fruiting bodies emerge only under precise conditions of soil moisture, temperature, and forest ecology. Foraging for this variety requires not just skill but also an understanding of its habitat—riverbanks, recently burned areas, or disturbed soils—where it often appears in spring.

To identify the half-free morel, look for its distinctive cap: a honeycomb pattern with ridges and pits, attached to the stem at the base but free at the top, giving it a skirt-like appearance. Its color ranges from blond to grayish-brown, and its size varies from 2 to 6 inches. Always carry a field guide or use a reliable app to confirm your find, as false morels (e.g., *Gyromitra*) resemble true morels but are toxic. Proper identification is critical; even experienced foragers occasionally mistake look-alikes.

Foraging for half-free morels is as much about timing as location. In North America, they typically appear in April and May, depending on latitude and weather. Early mornings after a rain are ideal, as the mushrooms are firmer and less likely to be infested with insects. Use a mesh bag to carry your harvest, allowing spores to disperse as you walk, and always leave some behind to ensure future growth. Avoid over-foraging in a single area to preserve the delicate balance of their ecosystem.

Cooking half-free morels enhances their nutty, earthy flavor. Clean them thoroughly by brushing off dirt and soaking in saltwater to remove insects. Sautéing in butter or olive oil highlights their texture, while drying or freezing preserves them for later use. Pair them with dishes like risotto, pasta, or omelets to elevate the meal. However, always cook them fully; consuming raw or undercooked morels can cause digestive discomfort.

The rarity of half-free morels—coupled with their resistance to cultivation—makes them a symbol of the wild food movement. Foragers prize them not just for their flavor but for the adventure of finding them. As climate change and habitat loss threaten their ecosystems, ethical foraging practices become even more crucial. By respecting their natural habitats and sharing knowledge responsibly, enthusiasts can help ensure these morels remain a treasure for generations to come.

Storing Magic Mushrooms: Room Temperature Tips and Best Practices

You may want to see also

Chanterelles in Forests: Golden chanterelles thrive in woodlands, never farmed, always foraged

Golden chanterelles, with their trumpet-like shape and vibrant hue, are a forager’s treasure, found exclusively in the wild. Unlike button mushrooms or shiitakes, which thrive in controlled environments, chanterelles refuse domestication. They form symbiotic relationships with trees, particularly oak, beech, and pine, exchanging nutrients with their roots in a delicate ecological dance. This mycorrhizal bond ensures their survival but also limits their cultivation, making them a true forest-dwelling species. Foragers must venture into woodlands, armed with knowledge and respect for nature, to find these elusive gems.

Identifying chanterelles requires a keen eye. Their egg-yolk color and forked, wavy gills are telltale signs, but beware of look-alikes like the jack-o’lantern mushroom, which is toxic. A practical tip: chanterelles emit a faint fruity aroma, often described as apricot-like, which can help confirm their identity. Always cut the mushroom at the base of the stem to preserve the mycelium, ensuring future growth. Foraging responsibly means taking only what you need and leaving the forest undisturbed.

From a culinary perspective, chanterelles are a chef’s dream. Their meaty texture and nutty flavor elevate dishes, from creamy sauces to hearty risottos. To prepare them, gently brush off dirt (avoid washing, as they absorb water), then sauté in butter or olive oil to enhance their natural richness. Pairing them with thyme, garlic, and white wine unlocks their full potential. A pro tip: dry excess chanterelles for year-round use; rehydrate them in warm water or stock to retain their flavor.

The allure of chanterelles extends beyond the kitchen. Their presence in a forest indicates a healthy ecosystem, as they thrive in undisturbed, biodiverse environments. Foraging for them becomes an act of connection—to nature, to tradition, and to the land. However, this privilege comes with responsibility. Overharvesting or damaging their habitat threatens not just the mushrooms but the entire woodland community. Always follow local foraging guidelines and obtain permits where required.

In a world of mass-produced food, chanterelles remind us of the value of the wild and untamed. Their refusal to be farmed underscores the importance of preserving natural habitats. Foraging for them is not just about the harvest; it’s about stewardship, patience, and the joy of discovery. As you wander through the forest, remember: chanterelles are a gift, not a commodity. Treat them—and their home—with the care they deserve.

Mushrooms in Dog Poop: Unlikely Growth or Common Occurrence?

You may want to see also

Truffle Hunting: Elusive truffles depend on specific trees and soil, impossible to cultivate

Truffles, often hailed as the "diamonds of the kitchen," are among the most elusive and prized mushrooms in the world. Unlike common button mushrooms, which can be cultivated in controlled environments, truffles stubbornly resist domestication. Their growth is inextricably tied to specific tree species and soil conditions, creating a symbiotic relationship that cannot be replicated artificially. This dependency makes truffle hunting not just a culinary pursuit but a fascinating intersection of ecology and gastronomy.

To understand why truffles can only be foraged, consider their unique biology. Truffles are the fruiting bodies of underground fungi that form mycorrhizal associations with tree roots, primarily oak, hazel, and beech. This partnership allows the fungus to exchange nutrients with the tree, but it requires precise soil pH, drainage, and mineral composition. For instance, the Périgord truffle (*Tuber melanosporum*) thrives in calcareous soils with a pH between 7.5 and 8.5, while the Italian white truffle (*Tuber magnatum*) prefers loamy, well-drained soils rich in calcium and magnesium. Attempts to cultivate truffles outside these conditions have consistently failed, underscoring their reliance on natural ecosystems.

Truffle hunting is both an art and a science, demanding patience, knowledge, and often a trained animal. Traditionally, pigs were used due to their keen sense of smell, but their tendency to eat the truffles led to the widespread adoption of dogs, particularly the Lagotto Romagnolo breed. Hunters must also understand the subtle signs of truffle presence, such as "brûlé"—a patch of burnt-looking vegetation caused by the truffle's mycelium altering soil chemistry. The hunt typically occurs in the cooler months, with peak season varying by truffle species: winter for Périgord and white truffles, and autumn for summer truffles (*Tuber aestivum*).

The impossibility of cultivating truffles has significant economic and cultural implications. Their scarcity drives prices to astronomical levels, with white truffles fetching up to $4,000 per pound. This has created a global market centered on regions like Piedmont in Italy, Périgord in France, and more recently, truffle farms in Australia and the Pacific Northwest, which rely on inoculated trees but still cannot control the yield. The mystique of truffle hunting, combined with their unattainable nature, has cemented their status as a luxury item, reserved for the most discerning palates.

For aspiring truffle hunters, success lies in understanding the truffle's habitat and forming a partnership with a skilled animal. Beginners should start by studying local truffle species and their associated trees, then invest in training a dog to detect the faint, garlicky aroma of truffles. While the hunt may be challenging, the reward—unearthing a truffle that no human hand could cultivate—is unparalleled. In a world of mass production, truffles remain a testament to the wild, untamed beauty of nature.

Freezing Mushrooms: A Complete Guide to Preserving Freshness and Flavor

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$13.5 $21.99

Lion’s Mane in Nature: This shaggy mushroom grows on decaying trees, not in farms

In the wild, Lion's Mane mushrooms (Hericium erinaceus) are a striking sight, often found clinging to the sides of decaying hardwood trees like oak, walnut, or maple. Their distinctive appearance—a cascading mass of long, shaggy spines resembling a lion’s mane—sets them apart from other fungi. Unlike cultivated varieties, which are often grown on sterile substrates like sawdust or grain, wild Lion's Mane thrives in the unpredictable, nutrient-rich environment of decomposing wood. This natural habitat contributes to its unique flavor profile and potentially higher concentrations of bioactive compounds, such as hericenones and erinacines, which are linked to cognitive and neurological benefits.

Foraging for Lion's Mane requires patience and a keen eye. These mushrooms typically appear in late summer to early fall in temperate forests of North America, Europe, and Asia. When identifying them, look for their pure white color (though they may yellow with age) and their lack of a traditional cap and stem structure. A key distinction from similar species, like the toxic *Clathrus archeri*, is their spine-like growths, which hang downward and can grow up to 20 centimeters long. Always cut the mushroom at the base rather than pulling it out, as this preserves the mycelium and allows for future growth.

While Lion's Mane can be cultivated, foraged specimens are prized for their potency and flavor. Studies suggest that wild varieties may contain higher levels of beta-glucans and polysaccharides, compounds associated with immune support and anti-inflammatory effects. To harness these benefits, foragers often dry the mushrooms for long-term storage or use them fresh in culinary applications. A common preparation is to sauté them in butter or olive oil, highlighting their seafood-like texture and mild, slightly nutty taste. For medicinal use, a typical dosage is 1–3 grams of dried mushroom per day, often consumed as a tea or tincture.

Foraging Lion's Mane is not without challenges. Their preference for decaying hardwood means they are often found in dense, mature forests, requiring careful navigation. Additionally, their seasonal and sporadic appearance demands multiple trips to locate a substantial harvest. Ethical foraging practices are crucial: only take what you need, avoid overharvesting in a single area, and ensure you have proper identification skills to avoid toxic look-alikes. For beginners, joining a local mycological society or consulting a field guide can provide invaluable guidance.

In conclusion, Lion's Mane mushrooms embody the essence of foraged fungi—wild, untamed, and deeply connected to their environment. Their reliance on decaying trees for growth underscores the importance of preserving natural habitats. Whether sought for culinary delight or medicinal use, foraging for Lion's Mane offers a rewarding experience that cultivates a deeper appreciation for the intricate relationships between fungi and their ecosystems. Just remember: respect the forest, and it will share its treasures.

Growing Mushrooms from Dried: Is It Possible? Here's How

You may want to see also

Porcini in the Wild: Found only in forests, porcini mushrooms cannot be commercially grown

Porcini mushrooms, scientifically known as *Boletus edulis*, are a forager’s treasure, prized for their rich, nutty flavor and meaty texture. Unlike button mushrooms or shiitakes, which thrive in controlled environments, porcini have eluded commercial cultivation despite decades of research. Their symbiotic relationship with specific tree species, such as pines and oaks, makes them dependent on forest ecosystems. This unique bond ensures that porcini can only be found in the wild, where they form mycorrhizal networks with tree roots, exchanging nutrients in a delicate ecological dance. Foraging for porcini is not just a culinary pursuit but a lesson in the interconnectedness of forest life.

To successfully forage porcini, timing and location are critical. These mushrooms emerge in late summer to early autumn, favoring temperate forests with well-drained, acidic soil. Look for them under coniferous or deciduous trees, often in clusters or singly. A key identifier is their distinct bulbous stem and brown, spongy pores beneath the cap. Avoid confusing them with toxic look-alikes like the Satan’s Bolete (*Boletus satanas*), which has a reddish stem and pores. Always carry a field guide or consult an expert if uncertain. Remember, sustainable foraging means harvesting only what you need and leaving enough mushrooms to spore and regenerate.

The inability to commercially grow porcini adds to their allure and exclusivity. This limitation has created a global market for wild-harvested porcini, particularly in Europe and North America, where they are dried, frozen, or sold fresh at premium prices. However, this demand has also led to overharvesting in some regions, threatening local ecosystems. Foragers must adhere to ethical practices, such as avoiding young mushrooms to allow them to mature and disperse spores. Additionally, respecting local regulations and private property rights is essential to preserve both the resource and the tradition of porcini foraging.

For those new to porcini foraging, start by joining guided mushroom hunts or local mycological societies. These groups provide hands-on experience and valuable insights into identifying and sustainably harvesting porcini. Equip yourself with a knife, basket (not plastic bags, which can cause spoilage), and a brush for cleaning dirt from the mushrooms. Once harvested, porcini can be sautéed, grilled, or dried for long-term storage. Their versatility in the kitchen—from risottos to soups—makes the effort of foraging well worth it. Just remember, the true reward lies not just in the meal but in the connection to nature’s rhythms and mysteries.

Can You Die from Eating Morel Mushrooms? Uncovering the Truth

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mushrooms like the Truffle (e.g., Périgord or Italian White Truffle) and Matsutake are highly prized and can only be foraged in the wild, as they are difficult or impossible to cultivate commercially.

Yes, Chanterelle mushrooms are primarily foraged in the wild, as they have a symbiotic relationship with trees and are challenging to cultivate artificially.

Morels are predominantly foraged, as their complex growth requirements make successful cultivation rare and inconsistent.

Porcini mushrooms (also known as Cep or King Bolete) are almost exclusively foraged, as they rely on specific forest ecosystems and cannot be reliably cultivated.

While Lion's Mane mushrooms can be cultivated, the majority found in markets are foraged due to their natural habitat in decaying hardwood trees.