North Carolina’s diverse ecosystems, ranging from the Appalachian Mountains to the coastal plains, provide a rich habitat for a variety of wild mushrooms. While many species are toxic or inedible, the state is also home to several delicious and safe-to-eat mushrooms, such as the prized chanterelles, lion’s mane, and morels. Foraging for wild mushrooms can be a rewarding activity, but it requires careful identification and knowledge to avoid dangerous look-alikes. Always consult a field guide or expert before consuming any wild fungi, and remember that proper preparation is key to enjoying these natural treasures safely.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Chanterelles: Golden, fruity, and abundant in NC forests, a forager's favorite for their flavor

- Lion's Mane: Shaggy, seafood-like texture, found on hardwood trees, unique culinary uses

- Oyster Mushrooms: Fan-shaped, grow on wood, mild taste, easy to identify and cook

- Morels: Honeycomb caps, spring delicacy, highly prized for rich, earthy flavor

- Chicken of the Woods: Bright orange, shelf-like clusters, tastes like chicken when cooked

Chanterelles: Golden, fruity, and abundant in NC forests, a forager's favorite for their flavor

In the lush, verdant forests of North Carolina, a treasure hunt awaits the discerning forager: the quest for chanterelles. These golden, trumpet-shaped mushrooms are not just a feast for the eyes but a culinary delight, prized for their fruity aroma and delicate flavor. Unlike the elusive morel, chanterelles are relatively easy to spot, often growing in clusters under hardwood trees like oak and beech. Their vibrant color and forked, gill-like ridges make them stand out against the forest floor, though beginners should always consult a reliable guide or expert to avoid look-alikes like the jack-o’-lantern mushroom, which can cause gastrointestinal distress.

Foraging for chanterelles is as much an art as it is a science. The best time to search is late summer to early fall, when the soil is warm and moist. Equip yourself with a mesh bag to allow spores to disperse as you walk, a small knife for clean cuts at the base, and a brush to remove dirt without damaging the mushroom. Chanterelles are abundant in NC’s Appalachian region, particularly in areas with rich, loamy soil. Remember, sustainability is key—only harvest what you can use, and leave plenty behind to ensure future growth.

Once you’ve gathered your chanterelles, their culinary potential is vast. Their fruity, apricot-like scent pairs beautifully with eggs, pasta, and creamy sauces. To prepare, gently clean the mushrooms with a brush or damp cloth to preserve their delicate texture. Sauté them in butter with garlic and thyme for a simple yet exquisite side dish, or dry them for long-term storage to enjoy their flavor year-round. Unlike some wild mushrooms, chanterelles are best enjoyed cooked, as heat enhances their aroma and softens their chewy texture.

What sets chanterelles apart is their versatility and accessibility. While some wild mushrooms require meticulous preparation or have a narrow window of edibility, chanterelles are forgiving and consistently delicious. Their flavor profile bridges the gap between earthy and fruity, making them a favorite among chefs and home cooks alike. For the adventurous forager, chanterelles are not just a meal—they’re a connection to the forest, a reward for patience and observation, and a reminder of the bounty that lies just beyond the beaten path.

Can Raw Mushrooms Carry E. Coli? Facts and Food Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Lion's Mane: Shaggy, seafood-like texture, found on hardwood trees, unique culinary uses

In the lush forests of North Carolina, foragers often stumble upon the Lion’s Mane mushroom (*Hericium erinaceus*), a striking fungus that resembles a cascading clump of icicles or a lion’s shaggy mane. Unlike the typical cap-and-stem mushrooms, its tooth-like spines hang in clusters, growing predominantly on hardwood trees like oak, beech, and maple. This mushroom’s texture is its culinary claim to fame: when cooked, it transforms into a tender, seafood-like consistency that mimics crab or lobster meat, making it a favorite among chefs and home cooks alike.

To harvest Lion’s Mane, look for it in late summer to early fall, typically at elevations above 2,000 feet in the Appalachian region. When foraging, ensure the mushroom is pure white or slightly yellow; avoid specimens with dark, mushy spots, as these indicate overmaturity or decay. Use a sharp knife to cut the mushroom at its base, leaving enough behind to allow regrowth. Always cook Lion’s Mane thoroughly—its raw texture is unpleasantly spongy, but sautéing, frying, or baking it unlocks its delicate, buttery flavor and seafood-like mouthfeel.

Culinary creativity flourishes with Lion’s Mane. For a simple yet impressive dish, tear the mushroom into bite-sized pieces, coat them in a batter of flour, egg, and panko breadcrumbs, then fry until golden. Serve with a lemon-garlic aioli for a vegan crab cake alternative. Alternatively, slice it thinly, marinate in soy sauce and ginger, and grill for a savory steak-like entrée. Its versatility extends to soups, stir-fries, and even as a meat substitute in tacos or po’boys. For a health-conscious twist, Lion’s Mane is rich in bioactive compounds like beta-glucans and hericenones, which studies suggest may support cognitive function and nerve health.

Despite its culinary allure, caution is paramount. Always verify your find with a field guide or expert, as poisonous look-alikes like the Tooth Hedgehog (*Hydnum repandum*) lack Lion’s Mane’s distinct shaggy appearance. Additionally, while it’s safe for most people, those with mushroom allergies or sensitive stomachs should start with small portions. Foraging responsibly is equally critical—harvest sustainably by taking only what you need and avoiding over-collection in a single area.

In North Carolina’s wild mushroom scene, Lion’s Mane stands out as a forager’s treasure and a chef’s secret weapon. Its unique texture, paired with its ability to elevate both simple and sophisticated dishes, makes it a must-try for anyone exploring the state’s edible fungi. Whether you’re a seasoned forager or a curious cook, this mushroom offers a gateway to a world where the forest meets the kitchen in unexpected, delicious ways.

Can Mushrooms Cause a Failed Drug Test? What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

Oyster Mushrooms: Fan-shaped, grow on wood, mild taste, easy to identify and cook

Oyster mushrooms, with their distinctive fan-shaped caps and wood-loving nature, are a forager’s dream in North Carolina’s forests. Unlike many wild mushrooms that require expert identification, oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus) are relatively easy to spot thanks to their grayish-brown, shell-like appearance and tendency to grow in clusters on decaying hardwood trees. Their mild, slightly sweet flavor makes them a versatile addition to any meal, from stir-fries to soups, without overwhelming other ingredients.

Identifying oyster mushrooms correctly is crucial, but fortunately, they have few dangerous look-alikes. Key features to look for include their decurrent gills (gills that run down the stem), lack of a ring on the stem, and their preference for growing on wood rather than directly in soil. One caution: avoid mushrooms growing on coniferous trees, as these are likely a different, potentially toxic species. Always carry a field guide or use a reliable mushroom identification app to confirm your find.

Cooking oyster mushrooms is straightforward, but proper preparation enhances their texture and flavor. Start by gently brushing off dirt or debris—avoid washing them, as they absorb water easily. Sautéing in butter or olive oil over medium heat until they’re golden brown and slightly crispy is a classic method. For a meatier texture, marinate them in soy sauce, garlic, and a touch of oil before grilling or roasting. Their mild taste pairs well with garlic, thyme, and lemon, making them a perfect addition to pasta dishes or risottos.

Foraging for oyster mushrooms in North Carolina is best done in the cooler months, typically from late fall to early spring, when they thrive in the state’s temperate climate. Look for them on fallen oak, beech, or maple trees in wooded areas. Always forage sustainably by leaving some mushrooms behind to spore and ensure future growth. If you’re new to foraging, consider joining a local mycological society or going on a guided mushroom hunt to build your skills and confidence.

Incorporating oyster mushrooms into your diet not only adds variety but also provides health benefits. They’re low in calories, rich in antioxidants, and a good source of protein and fiber. Studies suggest they may support immune health and have anti-inflammatory properties. Whether you’re a seasoned forager or a curious cook, oyster mushrooms offer a rewarding, accessible way to connect with North Carolina’s natural bounty. Just remember: when in doubt, throw it out—never consume a mushroom unless you’re 100% certain of its identity.

Mushroom Coffee and Fasting: Does It Break Your Fast?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

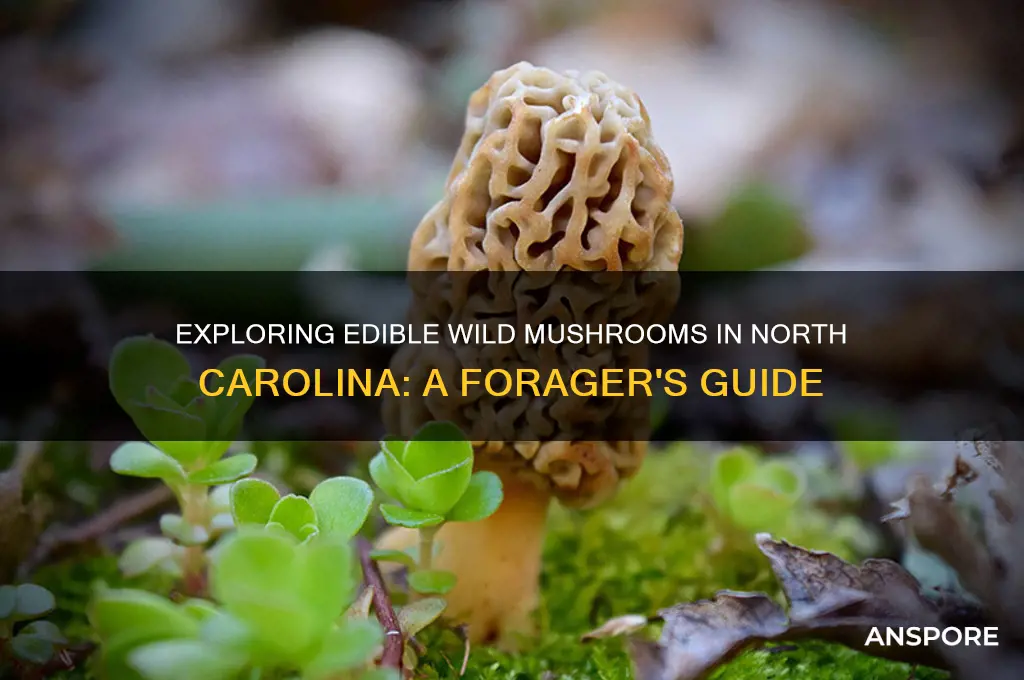

Morels: Honeycomb caps, spring delicacy, highly prized for rich, earthy flavor

Morels, with their distinctive honeycomb caps, are a springtime treasure for foragers in North Carolina. These elusive fungi emerge in deciduous forests, often near ash, elm, and poplar trees, after the soil warms and spring rains have soaked the ground. Their spongy, cone-like structure isn’t just visually striking—it’s a key identifier that distinguishes them from toxic look-alikes like false morels. While morels are safe to eat when properly identified and cooked, consuming them raw or misidentifying them can lead to severe gastrointestinal distress. Always cross-reference findings with a reliable field guide or consult an experienced forager.

The rich, earthy flavor of morels makes them a culinary prize, often compared to a blend of nutty and smoky notes with a meaty texture. Chefs and home cooks alike prize them for their ability to elevate dishes, from creamy pasta sauces to simple sautéed sides. To preserve their delicate flavor, cook morels gently—sauté them in butter or olive oil over medium heat until they release their moisture and turn golden. Avoid overcrowding the pan, as this can cause them to steam rather than brown. For long-term storage, dehydrate morels and rehydrate them in warm water or broth before use, retaining much of their original flavor.

Foraging for morels in North Carolina requires patience and respect for the environment. Spring is their prime season, typically from late March through May, depending on temperature and rainfall. Look for them in areas with well-drained soil and partial sunlight, often at the base of trees or along south-facing slopes. When harvesting, use a knife to cut the stem at the base, leaving the mycelium undisturbed to encourage future growth. Remember, overharvesting can deplete local populations, so collect only what you need and leave some behind to spore.

While morels are a forager’s dream, caution is paramount. False morels, with their wrinkled, brain-like caps, contain gyromitrin, a toxin that breaks down into monomethylhydrazine, a component of rocket fuel. Ingesting false morels can cause symptoms ranging from nausea to seizures, and in severe cases, organ failure. Always cook morels thoroughly, as heat destroys any trace toxins present in true morels and improves digestibility. If in doubt, skip the find—the risk of misidentification far outweighs the reward of a meal.

For those new to morel hunting, start by joining local foraging groups or workshops to learn from experienced guides. Bring a mesh bag for collecting, as it allows spores to disperse while you walk. Dress appropriately with long pants, sturdy boots, and insect repellent, as spring forests can be buggy and uneven. Finally, obtain permission before foraging on private land and adhere to state regulations, as some areas may have restrictions. With knowledge, caution, and respect, morels can become a cherished annual tradition, connecting you to the rhythms of North Carolina’s natural world.

Where to Buy Mellow Mushroom Esperanza Dressing: A Tasty Guide

You may want to see also

Chicken of the Woods: Bright orange, shelf-like clusters, tastes like chicken when cooked

In the lush forests of North Carolina, foragers often stumble upon Chicken of the Woods (*Laetiporus sulphureus*), a mushroom that lives up to its name. Its vibrant orange, shelf-like clusters cling to tree trunks, particularly oak, mimicking the appearance of a roasted chicken when cooked. This fungus is not just a visual spectacle but a culinary treasure, offering a meaty texture and flavor that can satisfy even the most skeptical omnivore. However, its identification requires precision; while it’s a prized edible, similar species like *Laetiporus conifericola* (found on conifers) can cause digestive upset in some individuals. Always ensure the mushroom grows on hardwoods and performs a spore print test to confirm its bright white spores.

Foraging for Chicken of the Woods is an exercise in observation and patience. Look for its fan-shaped caps, often tiered like shelves, ranging from bright orange to dull brown as it ages. Younger specimens are ideal, as they retain a tender texture and mild flavor. Harvest only a portion of the cluster to allow the fungus to regenerate, a sustainable practice that ensures future harvests. Once collected, clean the mushrooms thoroughly to remove debris and insects, as their nooks and crannies can harbor unwanted guests. Cooking is essential—never consume this mushroom raw, as it can cause gastrointestinal distress. Sautéing, grilling, or breading and frying are popular methods that highlight its chicken-like qualities.

From a culinary perspective, Chicken of the Woods is a versatile ingredient. Its ability to absorb flavors makes it an excellent candidate for marinades, particularly those with garlic, lemon, and herbs. For a simple yet satisfying dish, slice the mushroom into "cutlets," coat in a mixture of flour, egg, and breadcrumbs, and fry until golden. Pair it with a side of roasted vegetables and a tangy sauce for a meal that rivals any meat-based entrée. Vegans and vegetarians often use it as a protein substitute, while omnivores appreciate its unique texture in stews and stir-fries. However, moderation is key; some individuals report mild reactions even when cooked, so start with small portions to test tolerance.

Despite its culinary appeal, Chicken of the Woods demands respect. Misidentification can lead to confusion with toxic species like *Stereum hirsutum* (false turkey tail), which lacks its vibrant color and shelf-like structure. Always cross-reference findings with a reliable field guide or consult an experienced forager. Additionally, avoid harvesting near roadsides or industrial areas, as mushrooms can accumulate toxins from their environment. Proper storage is equally important—refrigerate fresh specimens in paper bags to maintain freshness, or dehydrate them for long-term use. With its striking appearance and remarkable flavor, Chicken of the Woods is a forager’s reward, but its safe and sustainable collection is paramount.

Rum and Mushrooms: An Unexpected Pairing Worth Exploring

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Common edible wild mushrooms in North Carolina include the Lion's Mane (Hericium erinaceus), Chicken of the Woods (Laetiporus sulphureus), Chanterelles (Cantharellus spp.), and Morel mushrooms (Morchella spp.). Always verify identification before consuming.

Yes, several poisonous mushrooms in North Carolina resemble edible species. For example, the Jack-O-Lantern (Omphalotus olearius) looks similar to Chicken of the Woods, and false morels (Gyromitra spp.) can be mistaken for true morels. Proper identification is crucial.

The best time to forage for wild mushrooms in North Carolina is during the spring and fall, when moisture and temperature conditions are ideal for mushroom growth. Spring is prime for morels, while fall is better for chanterelles and Lion's Mane.

Foraging for wild mushrooms on public lands in North Carolina is generally allowed for personal use, but rules vary by location. Always check with local land management agencies, such as state parks or national forests, for specific regulations and permits.