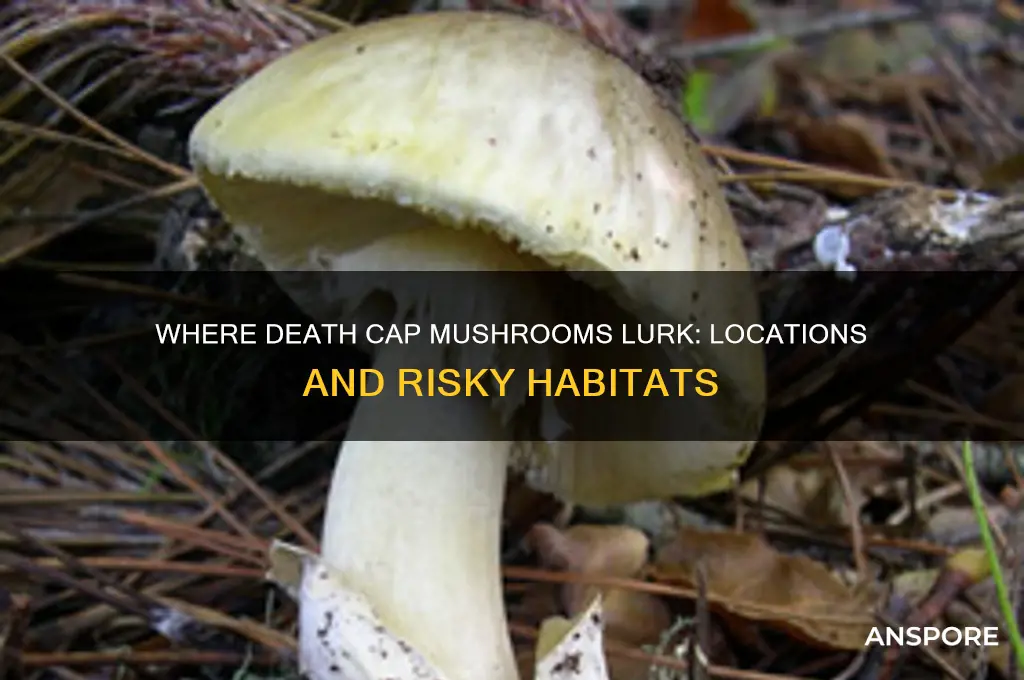

The death cap mushroom (*Amanita phalloides*) is one of the most poisonous fungi in the world, responsible for the majority of fatal mushroom poisonings globally. Native to Europe, it has spread to other regions, including North America, Australia, and New Zealand, often introduced through imported trees or soil. Death caps thrive in temperate climates and are commonly found in deciduous and coniferous forests, particularly under oak, beech, and pine trees, where they form symbiotic relationships with tree roots. They are most prevalent in the fall but can appear in spring and summer, depending on local conditions. Their ability to grow in urban areas, such as parks and gardens, makes them a significant risk to foragers and curious individuals, emphasizing the importance of accurate identification and caution when encountering wild mushrooms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Geographical Distribution | Europe, North America, Australia, Asia, and New Zealand |

| Habitat | Deciduous and coniferous forests, particularly under oak, beech, and pine |

| Soil Preference | Rich, calcareous soils; often found in areas with chalk or limestone |

| Climate | Temperate climates with moderate rainfall |

| Seasonal Appearance | Late summer to autumn (August to November in the Northern Hemisphere) |

| Association with Trees | Mycorrhizal relationship with broadleaf and coniferous trees |

| Common Locations | Woodlands, parks, gardens, and urban areas with suitable tree species |

| Elevation Range | Typically found at low to moderate elevations |

| Avoidance Areas | Arid or extremely cold regions |

| Invasive Spread | Often introduced accidentally through imported soil or trees |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Geographical Distribution: Europe, North America, Asia, Australia, often in wooded areas with oak, beech, pine trees

- Preferred Habitats: Deciduous and coniferous forests, urban parks, gardens, near tree roots, moist environments

- Seasonal Occurrence: Late summer to fall, peak in September, depends on local climate and rainfall

- Soil Preferences: Rich, calcareous soil, often under trees, near decaying wood, avoids acidic conditions

- Global Spread: Introduced to new regions via imported trees, soil, or human activity, expanding range

Geographical Distribution: Europe, North America, Asia, Australia, often in wooded areas with oak, beech, pine trees

The death cap mushroom, *Amanita phalloides*, is a global menace with a penchant for temperate climates. Its geographical reach spans four continents: Europe, North America, Asia, and Australia. This distribution isn't random; it's intimately tied to the presence of specific tree species. Oak, beech, and pine trees act as silent accomplices, providing the symbiotic relationship these fungi crave. Their mycelium intertwines with tree roots, forming a mutually beneficial network that allows the death cap to thrive in the dappled shade of these wooded areas.

Key Takeaway: If you're foraging in regions with these tree species, especially during autumn, extreme caution is paramount.

While the death cap's preference for wooded areas is consistent, its specific habitat within these environments can vary. In Europe, they often appear in deciduous forests, particularly those dominated by oak and beech. North American sightings frequently occur in coniferous forests with pine and spruce. Asia presents a broader picture, with death caps found in both deciduous and coniferous forests, often associated with oak and chestnut trees. Australia, a relatively recent addition to the death cap's territory, sees them thriving in eucalyptus forests, highlighting the fungus's adaptability.

Practical Tip: Familiarize yourself with the dominant tree species in your local wooded areas. This knowledge can significantly reduce the risk of accidental encounters.

The death cap's global spread is a relatively recent phenomenon, largely attributed to human activity. Its introduction to new territories often occurs through the importation of infected plant material or soil. Once established, the fungus can spread rapidly through its extensive mycelial network. This underscores the importance of responsible gardening practices and the need for strict regulations on the import of plant material.

Cautionary Note: Never assume a mushroom is safe based on its location. Even within familiar wooded areas, the presence of death caps can be unpredictable.

Despite its widespread distribution, the death cap's toxicity remains constant. Ingesting just half a cap can be fatal to an adult, and even smaller amounts can be dangerous to children. The symptoms of poisoning are delayed, often appearing 6-24 hours after ingestion, making early diagnosis crucial. Critical Information: If you suspect death cap ingestion, seek immediate medical attention. Time is of the essence, and prompt treatment significantly improves the chances of survival.

Overripe Mushrooms: Health Risks and Safe Consumption Tips

You may want to see also

Preferred Habitats: Deciduous and coniferous forests, urban parks, gardens, near tree roots, moist environments

The death cap mushroom, *Amanita phalloides*, thrives in environments that offer both shade and moisture, making deciduous and coniferous forests its primary natural habitats. These forests provide the ideal conditions for its mycorrhizal relationship with tree roots, particularly those of oak, beech, and pine. This symbiotic association allows the fungus to exchange nutrients with the trees, ensuring its survival and proliferation. Foragers should exercise extreme caution in these areas, as death caps often blend seamlessly with edible species like chanterelles or oyster mushrooms, increasing the risk of accidental ingestion.

Urban parks and gardens have become unexpected hotspots for death cap mushrooms due to their adaptability to human-altered environments. The presence of ornamental trees, mulch, and irrigated lawns mimics their natural forest habitat, enabling them to flourish in residential areas. Homeowners who use wood chips or compost may inadvertently create the perfect breeding ground for these toxic fungi. To mitigate risk, regularly inspect garden beds, especially after rainy periods, and avoid consuming wild mushrooms without expert identification. Even a small bite of a death cap contains enough amatoxins to cause severe liver and kidney damage, often fatal if untreated.

Moist environments are non-negotiable for death caps, which explains their prevalence in regions with high humidity or frequent rainfall. They often appear after heavy rains, sprouting near tree bases where water accumulates. This preference for dampness also makes them common in riverbanks, floodplains, and areas with poor drainage. Foragers in such environments should prioritize carrying a field guide and a knife to examine mushrooms closely, looking for telltale death cap features like a volva (cup-like base) and a skirt-like ring on the stem. Remember, no culinary preparation can neutralize their toxins, making accurate identification critical.

Comparing their habitats to those of edible mushrooms highlights the danger of misidentification. While species like porcini or morels often grow in similar forested areas, death caps are more versatile, appearing in both wild and urban settings. This adaptability underscores the importance of habitat awareness rather than relying solely on mushroom morphology. For instance, a death cap found in a suburban garden may look identical to one in a remote forest, but both pose the same lethal threat. Always treat mushroom foraging as a high-stakes activity, especially in regions where death caps are endemic, such as North America, Europe, and Australia.

Moldy Magic Mushrooms: Safe to Eat or Risky Business?

You may want to see also

Seasonal Occurrence: Late summer to fall, peak in September, depends on local climate and rainfall

The death cap mushroom, *Amanita phalloides*, emerges with a clockwork precision tied to the rhythms of late summer and fall. Its appearance is not arbitrary but a response to environmental cues, primarily temperature and moisture. In regions with temperate climates, such as North America, Europe, and Australia, these fungi begin to fruit as the heat of summer wanes, typically from August through October. The peak occurs in September, when conditions are often ideal: cooler nights, warmer days, and sufficient rainfall to moisten the soil. This seasonal pattern is critical for foragers and the public alike, as it narrows the window of risk for accidental ingestion.

Understanding the local climate is essential for predicting the death cap’s emergence. In Mediterranean climates, where the fungus is invasive, its fruiting may align with the first autumn rains after a dry summer. For instance, in California, the first significant rainfall in October or November often triggers a flush of death caps. Conversely, in cooler, wetter regions like the Pacific Northwest, fruiting may begin earlier, in late August, and persist into October. Rainfall is the linchpin: without adequate moisture, mycelium remains dormant, and fruiting bodies fail to develop. Foraging safety tips emphasize avoiding mushroom collection during these peak months in known habitats, such as under oak, beech, or pine trees, where death caps form symbiotic relationships with tree roots.

A comparative analysis of global occurrences reveals how latitude and climate modulate the death cap’s seasonality. In Southern Europe, where the fungus is native, fruiting aligns with cooler autumn temperatures, often September to November. In contrast, New Zealand’s milder climate allows fruiting from March to May, mirroring the Southern Hemisphere’s autumn. This adaptability underscores the importance of local knowledge: what holds true for one region may not apply elsewhere. For instance, while September is a peak month in the Northern Hemisphere, foragers in Australia should be vigilant from late February through April.

For those living in areas where death caps are prevalent, practical precautions are paramount during their fruiting season. Avoid picking wild mushrooms for consumption unless you are an experienced mycologist. Teach children to recognize the death cap’s distinctive features: a pale green cap, white gills, and a bulbous base with a cup-like volva. Pets are also at risk, so monitor them during walks in wooded areas. If ingestion is suspected, immediate medical attention is critical; the toxin amatoxin can cause liver failure within 48 hours. Hospitals may administer activated charcoal or silibinin, a milk thistle derivative, to mitigate effects, but time is of the essence.

In conclusion, the death cap’s seasonal occurrence is a predictable yet perilous phenomenon. By recognizing the environmental triggers—late summer to fall, peak in September, and dependence on rainfall—individuals can minimize risk. This knowledge transforms a potentially deadly hazard into a manageable concern, emphasizing the interplay between nature’s cycles and human awareness. Whether in California’s oak woodlands or Europe’s deciduous forests, vigilance during these months is the first line of defense.

Can Drug Tests Detect Mushrooms? Psilocybin Testing Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Soil Preferences: Rich, calcareous soil, often under trees, near decaying wood, avoids acidic conditions

Death cap mushrooms, scientifically known as *Amanita phalloides*, are notoriously toxic and thrive in specific soil conditions. Their preference for rich, calcareous soil is a key factor in their distribution. Calcareous soil, characterized by a high calcium carbonate content, often provides the alkaline environment these fungi favor. This type of soil is commonly found in areas with limestone or chalky substrates, making regions like Europe, North America, and parts of Australia prime habitats for death caps. Understanding this soil preference is crucial for foragers and homeowners alike, as it helps identify potential danger zones.

For those venturing into wooded areas, knowing where to look is half the battle. Death caps are frequently found under trees, particularly deciduous species like oaks and beeches, where the soil is enriched by leaf litter and decaying wood. This symbiotic relationship with trees allows the mushrooms to access nutrients from the mycorrhizal network, a fungal web that connects plant roots. If you spot a cluster of mushrooms near a tree stump or in a patch of decaying wood, exercise caution—it could be a death cap colony. A practical tip: carry a soil pH testing kit to check for alkaline conditions, as acidic soil is a strong indicator that death caps are unlikely to be present.

The avoidance of acidic conditions by death caps highlights their ecological niche. While many mushrooms thrive in acidic environments, such as those found in coniferous forests, death caps are outliers. This preference for alkaline soil limits their range but also makes them more predictable. For instance, in regions with predominantly acidic soil, like the Pacific Northwest of the United States, death caps are rare. Conversely, areas with a history of lime application or natural limestone deposits are more likely to host these toxic fungi. Gardeners and landowners can use this knowledge to assess risk, especially if they’ve amended their soil with lime or planted deciduous trees.

To minimize the risk of accidental poisoning, focus on habitat disruption rather than eradication. Avoid creating ideal conditions for death caps by refraining from excessive lime application or planting deciduous trees in calcareous soil. If you suspect death caps are present, mark the area clearly and educate others, especially children, about their dangers. While these mushrooms play a role in their ecosystem, their toxicity demands respect and proactive measures. By understanding their soil preferences, you can coexist with nature while safeguarding your health.

Crispy Air-Fried Mushrooms: A Quick, Healthy Snack Recipe Guide

You may want to see also

Global Spread: Introduced to new regions via imported trees, soil, or human activity, expanding range

The death cap mushroom, *Amanita phalloides*, is no longer confined to its native European habitats. Its global spread is a cautionary tale of how human activity can inadvertently introduce deadly species to new regions. Imported trees, particularly oak and chestnut, often harbor death cap mycelium in their root systems, acting as silent carriers to distant lands. Soil contaminated with spores, transported through gardening supplies or construction materials, further facilitates this expansion. Even the movement of infected plant debris or the spores clinging to shoes and tools can introduce this toxic fungus to previously unaffected areas.

Consider the case of North America, where death caps were virtually unknown until the mid-20th century. The intentional planting of European tree species in urban and suburban areas created the perfect environment for these mushrooms to thrive. Today, they are found in California, the Pacific Northwest, and even the East Coast, often popping up in residential gardens and parks. This spread is not limited to the U.S.; Australia, New Zealand, and parts of South America have also reported infestations, linked to imported landscaping materials and trees.

To mitigate the risk, gardeners and landscapers must adopt vigilant practices. Inspect imported plants and soil for signs of fungal growth, and quarantine new additions before integrating them into existing ecosystems. For homeowners, avoid composting unknown mushrooms, as their spores can survive and spread. If you suspect death caps on your property, contact local mycological experts for identification and safe removal. Remember, even a small fragment of the mushroom or its mycelium can establish a new colony.

The global spread of death caps underscores the interconnectedness of ecosystems in our modern world. While their expansion is alarming, understanding the mechanisms of their introduction empowers us to take proactive measures. By being mindful of the materials we import and the practices we employ, we can limit the range of this deadly fungus and protect both human health and local biodiversity.

Can Mushrooms Cause Food Poisoning? Risks and Safe Consumption Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Death cap mushrooms (*Amanita phalloides*) are native to Europe but have spread to other regions, including North America, Australia, and New Zealand, often through introduced tree species like oaks, chestnuts, and pines.

Death caps thrive in wooded areas, particularly under deciduous and coniferous trees, where they form mycorrhizal relationships with tree roots. They prefer moist, shaded environments with rich soil.

Yes, death caps can appear in urban and suburban areas, especially near parks, gardens, or yards with trees like oaks or pines. They often grow in mulch or soil where trees are present.

Death caps are most commonly found in late summer to fall (August to November in the Northern Hemisphere), though their appearance can vary depending on local climate and conditions.