Finding poisonous mushrooms can be a dangerous endeavor, as many toxic species closely resemble edible varieties. They are commonly found in forested areas, particularly under deciduous and coniferous trees, as well as in grassy fields, gardens, and even urban parks. Poisonous mushrooms thrive in environments with ample moisture and organic matter, often appearing after rainfall. Some of the most notorious toxic species include the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*), Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*), and the Fool’s Mushroom (*Amanita verna*). It’s crucial to avoid foraging for mushrooms without expert guidance, as misidentification can lead to severe illness or even death. Instead, consult field guides, join mycological societies, or seek advice from experienced foragers to safely learn about these fungi.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Common Habitats | Woodlands, forests, grassy areas, decaying wood, and under trees. |

| Geographical Distribution | Worldwide, but more prevalent in temperate regions like North America, Europe, and Asia. |

| Seasonal Occurrence | Most common in late summer and autumn (fall), after rainfall. |

| Soil Preferences | Rich, moist soil, often near decaying organic matter. |

| Associated Plants | Found near oak, beech, pine, and other deciduous or coniferous trees. |

| Common Species | Amanita (e.g., Death Cap, Destroying Angel), Galerina, Cortinarius, and Lepiota. |

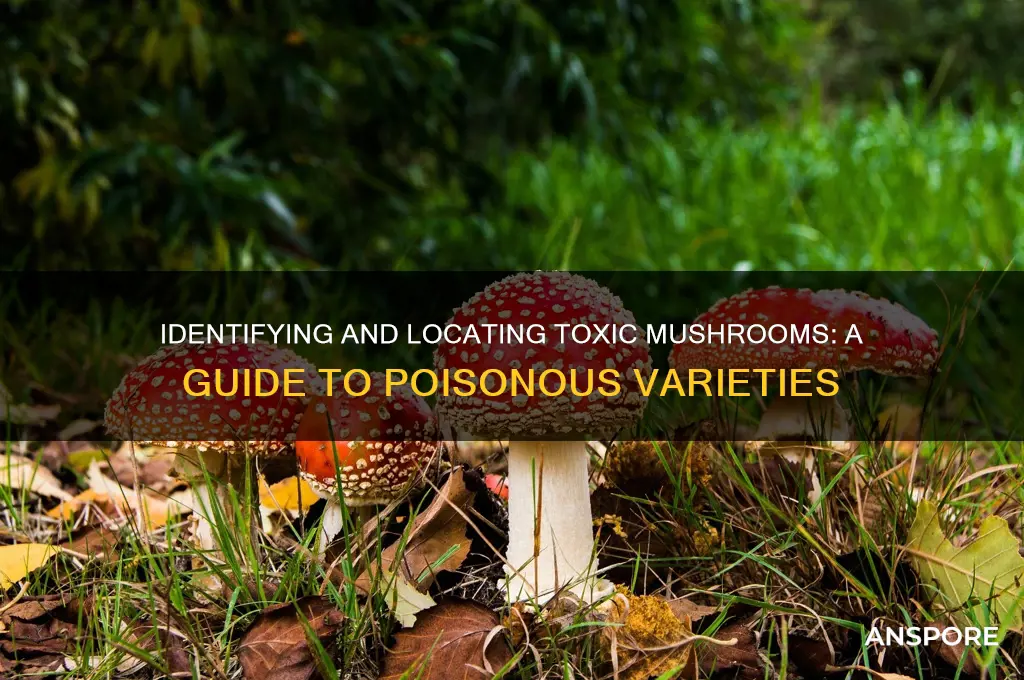

| Warning Signs | Bright colors (red, white, yellow), distinctive rings or volvas, and foul odors. |

| Avoidance Tips | Do not pick mushrooms unless you are an expert; avoid consuming wild mushrooms without proper identification. |

| Toxicity Levels | Varies; some cause mild gastrointestinal issues, while others are lethal (e.g., amatoxins in Amanita). |

| Symptoms of Poisoning | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, organ failure, and in severe cases, death. |

| Prevalence in Lawns | Can appear in lawns, especially those with trees or organic debris. |

| Commercial Availability | Poisonous mushrooms are not sold commercially; only edible varieties are available in markets. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Forests and Woodlands: Look in damp, shaded areas under trees, especially oak, birch, and pine

- Grasslands and Meadows: Check after rain in grassy fields, often near decaying organic matter

- Gardens and Yards: Found in mulch, compost piles, or under shrubs in residential areas

- Mountainous Regions: Grow in high-altitude forests, particularly in cooler, moist environments

- Wetlands and Swamps: Thrive in marshy areas with high humidity and waterlogged soil

Forests and Woodlands: Look in damp, shaded areas under trees, especially oak, birch, and pine

Damp, shaded areas under trees like oak, birch, and pine are prime real estate for poisonous mushrooms. These environments provide the perfect combination of moisture, organic matter, and shade that many toxic fungi thrive in. Foragers often overlook the importance of microclimates within forests, but understanding these conditions can be the difference between a safe harvest and a dangerous mistake. The Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*), for instance, frequently appears under oak trees in Europe and North America, blending seamlessly with its surroundings. Its innocuous appearance belies its deadly nature, as just 50 grams can cause severe liver and kidney damage in adults.

To safely explore these areas, start by familiarizing yourself with the common poisonous species in your region. Carry a detailed field guide or use a trusted mushroom identification app, but remember that technology is not infallible. Always cross-reference findings with multiple sources. When venturing into oak, birch, or pine forests, focus on the base of the trees, where decaying leaves and needles create a nutrient-rich substrate. Use a knife to carefully extract mushrooms for examination, preserving their base structure for identification. Avoid touching your face or eyes during collection, as some toxins can be absorbed through the skin.

A comparative analysis of these habitats reveals why certain trees attract poisonous mushrooms more than others. Oak trees, for example, release tannins into the soil, which some fungi have evolved to tolerate, including toxic species like the Death Cap. Birch trees, on the other hand, are often associated with the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*), a deceptively beautiful mushroom that contains amatoxins, lethal in doses as small as one cap. Pine forests may host the Fool’s Webcap (*Cortinarius orellanus*), which causes delayed kidney failure if consumed. Each tree species creates a unique soil chemistry, fostering specific fungal communities that foragers must learn to navigate.

For those new to mushroom hunting, a step-by-step approach can mitigate risks. First, limit your search to well-documented areas and seasons, typically late summer to early autumn. Second, focus on observing rather than collecting—photograph specimens in situ and note their habitat details. Third, if you choose to collect, isolate potentially poisonous mushrooms in a separate container. Finally, consult an expert or mycological society before consuming any wild fungi. Even experienced foragers occasionally misidentify mushrooms, so caution is paramount.

The takeaway is clear: forests and woodlands, particularly under oak, birch, and pine, are both treasure trove and minefield for mushroom enthusiasts. Their damp, shaded conditions nurture a variety of fungi, including some of the most toxic species known. By combining knowledge of habitat preferences, careful observation, and a healthy dose of skepticism, foragers can appreciate these ecosystems without endangering themselves. Remember, the goal is not just to find mushrooms, but to find them safely.

Mushrooms and Black Stool: Unraveling the Connection and Potential Causes

You may want to see also

Grasslands and Meadows: Check after rain in grassy fields, often near decaying organic matter

After a soaking rain, grasslands and meadows transform into fertile hunting grounds for mushroom enthusiasts and foragers alike. The damp soil, rich in decaying organic matter, provides the perfect environment for fungi to flourish. Among the benign varieties, however, lurk species that can be harmful or even deadly. For instance, the *Amanita virosa*, commonly known as the Destroying Angel, often emerges in these grassy fields, its pristine white cap and stem belying its lethal toxicity. A single bite can cause severe liver and kidney damage, with symptoms appearing 6 to 24 hours after ingestion. Foraging here requires vigilance, as these toxic species can closely resemble edible ones, such as the button mushroom.

To safely explore these areas, timing is crucial. The 24 to 48 hours following rain is prime time for mushroom growth, but it’s also when their features are most distinct, making identification easier. Equip yourself with a reliable field guide or a mushroom identification app, and always carry a knife to carefully excavate specimens for examination. Look for mushrooms growing near decaying wood, animal droppings, or leaf litter, as these are hotspots for nutrient-rich soil. Avoid touching your face while handling mushrooms, and wash your hands thoroughly afterward, as some toxins can be absorbed through the skin.

A comparative approach can be particularly useful in these environments. For example, the *Clitocybe dealbata*, or Ivory Funnel, thrives in grassy areas and is often mistaken for edible chanterelles due to its pale color and funnel-like shape. However, it contains muscarine, a toxin that causes sweating, salivation, and blurred vision within 15 to 30 minutes of ingestion. In contrast, the edible *Marasmius oreades*, or Fairy Ring Mushroom, also grows in grassy fields but lacks these toxins. Key differences include the Ivory Funnel’s sharper scent and more fragile gills.

For families or groups venturing into these habitats, education is paramount. Teach children to admire mushrooms from a distance and never touch or taste them without adult supervision. Even pets are at risk, as dogs are known to ingest toxic mushrooms like the *Galerina marginata*, which can be fatal within hours. If foraging for consumption, always cook mushrooms thoroughly, as some toxins are heat-sensitive. For instance, the toxin coprine in *Coprinus atramentarius* can cause severe reactions when consumed with alcohol, but cooking deactivates it.

In conclusion, grasslands and meadows offer a rewarding yet risky foraging experience. By focusing on post-rain periods, understanding toxin profiles, and employing careful identification techniques, you can minimize danger. Remember, when in doubt, leave it out. The beauty of these ecosystems lies not just in their flora but in the wisdom to navigate them safely.

Baby Bella vs. Cremini: Perfect Substitute or Recipe Risk?

You may want to see also

Gardens and Yards: Found in mulch, compost piles, or under shrubs in residential areas

Residential gardens and yards, often seen as safe havens, can harbor hidden dangers in the form of poisonous mushrooms. These fungi thrive in environments rich in organic matter, making mulch, compost piles, and the shaded areas under shrubs prime real estate. For instance, the Amanita genus, which includes the deadly Amanita phalloides (Death Cap), frequently appears in such settings, especially after rainy periods. Their innocuous appearance—often resembling common edible species—makes them particularly treacherous. A single bite can lead to severe liver and kidney damage, with symptoms appearing 6–24 hours after ingestion.

To minimize risk, homeowners should adopt proactive measures. Regularly inspect mulch and compost areas, particularly in autumn when mushroom growth peaks. Remove any suspicious fungi, ensuring children and pets cannot access them. Avoid using wild mushrooms in cooking unless identified by a mycologist. For compost piles, maintain proper aeration and moisture levels to discourage fungal growth without compromising decomposition. Remember, prevention is key; a well-maintained yard reduces the likelihood of toxic species taking root.

Comparing residential mushroom risks to those in forests highlights a critical difference: proximity. While woodland mushrooms may be more diverse, those in yards pose a higher threat due to frequent human and pet interaction. For example, the Galerina marginata, often found in wood chip mulch, contains the same toxins as the Death Cap but is smaller and easier to overlook. Unlike forest forays, where caution is expected, yard mushrooms often catch homeowners off guard, assuming their controlled environment is inherently safe.

Descriptively, these mushrooms often blend seamlessly into their surroundings. The Death Cap, with its olive-green cap and white gills, mimics harmless varieties like the Paddy Straw mushroom. Similarly, the Conocybe filaris, another yard dweller, grows in clusters on lawns or mulch, its slender stature making it easy to dismiss as benign. Their ability to flourish in disturbed soil—common in gardening—further complicates detection. Even experienced foragers can mistake them for edibles, underscoring the need for vigilance.

In conclusion, gardens and yards are not immune to poisonous mushrooms. By understanding their preferred habitats—mulch, compost, and shrub bases—and adopting preventive practices, homeowners can mitigate risks. Stay informed, act cautiously, and prioritize safety in these seemingly innocuous spaces. After all, knowledge and awareness are the best defenses against nature’s hidden threats.

Mushroom Spores and Asthma: Unveiling Potential Irritation Risks

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Mountainous Regions: Grow in high-altitude forests, particularly in cooler, moist environments

High-altitude forests, particularly those in cooler, moist environments, are prime habitats for a variety of poisonous mushrooms. These regions, often found in mountainous areas, provide the ideal conditions for species like the Amanita virosa (Destroying Angel) and Cortinarius rubellus (Deadly Webcap) to thrive. The combination of rich, organic soil, consistent moisture, and shaded canopies creates a microclimate that supports their growth. Foragers must exercise extreme caution in these areas, as many toxic species closely resemble edible varieties, such as the chanterelle or porcini.

To safely explore these regions, start by familiarizing yourself with the key identifiers of poisonous mushrooms. For instance, the Destroying Angel has a pure white cap and stem, often with a distinctive volva at the base, while the Deadly Webcap is recognized by its rusty-brown cap and cortina (a cobweb-like partial veil). Carry a reliable field guide or use a mushroom identification app, but remember that visual identification alone is not foolproof. Always cross-reference findings with multiple sources and, if unsure, avoid consumption entirely.

When foraging in mountainous forests, focus on areas with coniferous trees, such as spruce or fir, as these are common hosts for toxic species. Avoid collecting mushrooms near polluted areas or heavily trafficked trails, as toxins from the environment can accumulate in fungi. Time your visit during late summer to early autumn, when cooler temperatures and increased rainfall stimulate mushroom growth. However, be mindful of altitude-related weather changes; sudden storms can make conditions hazardous.

For those new to foraging, consider joining a guided tour led by a mycologist or experienced forager. These experts can provide hands-on instruction in identifying safe and toxic species, as well as tips for sustainable harvesting. If you’re foraging independently, collect only a few specimens of each type and note their location for future reference. Never consume a wild mushroom without 100% certainty of its identity, as even small doses of certain toxins (e.g., amatoxins in Amanita species) can cause severe liver damage or be fatal within 24–48 hours.

In conclusion, mountainous regions with high-altitude forests are both a treasure trove and a minefield for mushroom enthusiasts. Their cooler, moist environments foster a diverse array of fungi, including some of the most toxic species known. By combining knowledge, caution, and respect for these ecosystems, foragers can safely enjoy the wonders of these habitats without risking their health. Always prioritize safety over curiosity, and when in doubt, leave it out.

Mushroom-Free Chicken Marsala: A Delicious Alternative Recipe to Try

You may want to see also

Wetlands and Swamps: Thrive in marshy areas with high humidity and waterlogged soil

In the shadowy, waterlogged embrace of wetlands and swamps, a peculiar ecosystem thrives—one where poisonous mushrooms find their ideal habitat. These environments, characterized by high humidity and perpetually damp soil, create the perfect conditions for mycelium to flourish. Species like the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) and Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*) are notorious inhabitants, often blending seamlessly with their surroundings. Their toxicity lies in amatoxins, which can cause severe liver and kidney damage within 24–48 hours of ingestion. Even a small bite—as little as 30 grams—can be fatal to an adult.

To identify these dangers, focus on specific traits. Death Caps, for instance, have a greenish-yellow cap, white gills, and a distinctive volva at the base. They often grow near oak and beech trees in swampy areas. Destroying Angels, on the other hand, are pure white and resemble harmless button mushrooms, making them particularly deceptive. Always carry a reliable field guide or use a mushroom identification app when exploring these areas, but remember: visual identification alone is not foolproof.

Foraging in wetlands requires caution. Wear gloves to avoid skin contact with toxic spores, and never consume a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity. If you suspect poisoning, seek medical attention immediately. Symptoms like nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain appear 6–24 hours after ingestion, followed by a false "recovery" period before organ failure sets in. Time is critical—activated charcoal or syrup of ipecac can be administered in the first hour, but professional treatment is essential.

Comparatively, wetlands and swamps offer a stark contrast to drier environments where edible mushrooms like chanterelles or morels thrive. The constant moisture here fosters a different fungal community, one that demands respect and vigilance. While these ecosystems are biologically rich, they are not playgrounds for amateur foragers. Even experienced mycologists proceed with caution, often focusing on cultivation or controlled environments to study these species safely.

In conclusion, wetlands and swamps are both cradles of biodiversity and hotspots for poisonous mushrooms. Their allure lies in their mystery, but their dangers are very real. Approach these areas with curiosity, but prioritize safety. If in doubt, leave the mushrooms where they are—admiring their beauty without risking your health is the wisest choice.

Risks of Consecutive Magic Mushroom Use: Exploring Back-to-Back Trips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Poisonous mushrooms can be found in various habitats, including forests, meadows, and even urban areas. They often grow near trees, in decaying wood, or on the ground. Common species like the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) and Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*) are typically found in wooded areas.

No, poisonous mushrooms are found worldwide. However, specific species may be more prevalent in certain climates or regions. For example, the Death Cap is common in Europe and North America, while the Poison Fire Coral (*Podostroma cornu-damae*) is more frequently found in Japan and Korea.

Yes, poisonous mushrooms can grow in backyards, especially if there are trees, mulch, or decaying organic matter. Species like the Deadly Galerina (*Galerina marginata*) are known to grow in gardens and urban areas.

It is extremely rare to find poisonous mushrooms in reputable grocery stores or markets, as they carefully source and identify edible varieties. However, mislabeling or contamination can occur, so always purchase mushrooms from trusted sources.

Identifying poisonous mushrooms requires knowledge of specific traits, such as color, shape, gills, and spore print. However, many toxic species resemble edible ones, making identification difficult. It is safest to avoid consuming wild mushrooms unless you are an experienced forager or consult an expert.