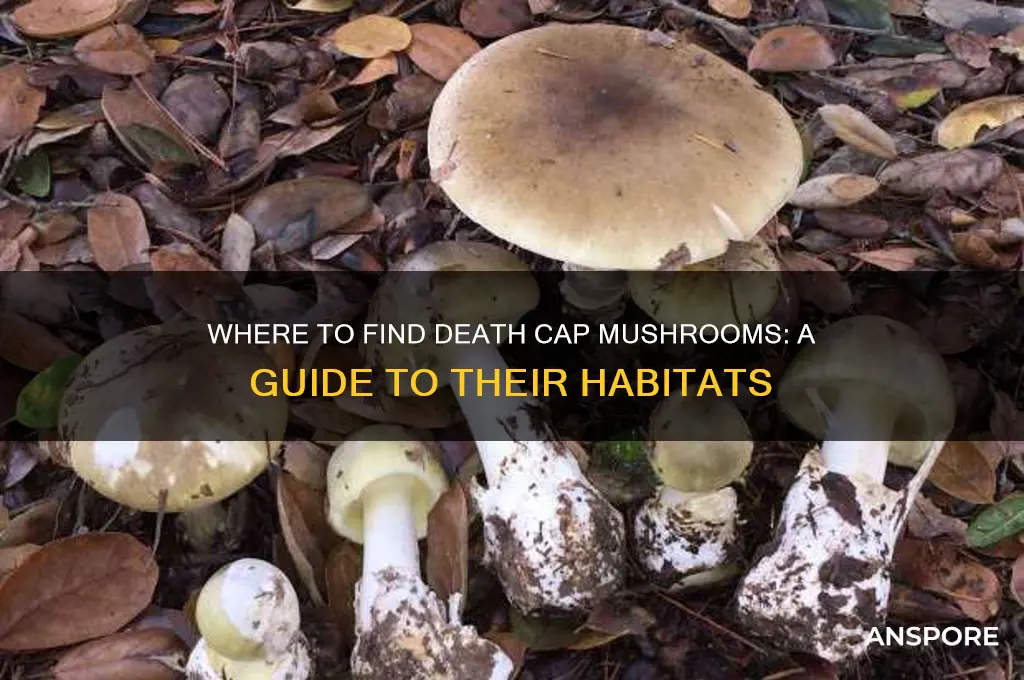

The Death Cap mushroom (*Amanita phalloides*) is one of the most poisonous fungi in the world, responsible for numerous fatal poisonings globally. It is crucial to know where this deadly mushroom can be found to avoid accidental ingestion. Native to Europe, the Death Cap has spread to other regions, including North America, Australia, and New Zealand, often appearing in deciduous and coniferous forests, particularly under oak, beech, and pine trees. It thrives in symbiotic relationships with tree roots, making it common in urban parks, gardens, and orchards where these trees are present. Its ability to resemble edible mushrooms, such as the straw mushroom or young puffballs, further increases the risk of misidentification. Awareness of its preferred habitats and distinctive features, such as its greenish cap, white gills, and bulbous base, is essential for anyone foraging in areas where it grows.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Scientific Name | Amanita phalloides |

| Common Names | Death Cap, Striking Amanita |

| Habitat | Deciduous and coniferous forests, often near oak, beech, and pine trees |

| Geographic Distribution | Europe, North America, Australia, and parts of Asia |

| Soil Preference | Mycorrhizal association with tree roots, prefers acidic to neutral soil |

| Season | Late summer to autumn (August to November in the Northern Hemisphere) |

| Appearance | Pale green to yellowish cap, white gills, bulbous base with a cup-like volva |

| Cap Diameter | 5–15 cm (2–6 inches) |

| Stem Height | 8–15 cm (3–6 inches) |

| Toxicity | Extremely toxic; contains amatoxins (e.g., alpha-amanitin) |

| Symptoms of Poisoning | Delayed onset (6–24 hours), gastrointestinal distress, liver/kidney failure |

| Edibility | Deadly poisonous; ingestion can be fatal |

| Look-Alikes | Young Amanita phalloides resembles edible mushrooms like Agaricus spp. |

| Conservation Status | Not endangered, but caution is advised due to toxicity |

| Prevention Tips | Avoid foraging without expert knowledge; always verify identification |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Forests with oak, beech, or chestnut trees

Death cap mushrooms (*Amanita phalloides*) thrive in symbiotic relationships with specific tree species, and forests dominated by oak, beech, or chestnut trees are prime habitats for these deadly fungi. This mycorrhizal association means the mushrooms depend on these trees for nutrients, often appearing at the base of the trees or scattered throughout the forest floor. If you’re foraging in such woodlands, particularly in Europe, North America, or Australia, exercise extreme caution—death caps can resemble edible species like young puffballs or immature button mushrooms, but ingesting even a small amount (as little as 50 grams) can be fatal due to their potent amatoxins.

For those exploring oak-beech-chestnut forests, understanding the seasonal patterns of death caps is crucial. These mushrooms typically fruit in late summer to fall, coinciding with cooler, moist conditions. Look for them in well-drained, slightly acidic soil, often in clusters or fairy rings. While their greenish-yellow caps and white gills might seem unassuming, their presence near these tree species is a red flag. Always carry a reliable field guide and avoid touching or picking any mushroom unless you’re 100% certain of its identity—even skin contact can transfer spores or toxins.

Comparing death caps to their benign counterparts in these forests highlights the importance of meticulous identification. For instance, the chestnut bolete (*Gyroporus castaneus*) shares a similar habitat but is edible and has a distinct brown cap and spongy pores. Unlike the death cap’s smooth stem with a cup-like volva at the base, the chestnut bolete lacks these features. This comparison underscores why foragers must focus on key characteristics like stem structure, gill color, and the presence of a volva—details that can mean the difference between a safe meal and a fatal mistake.

If you suspect you’ve encountered a death cap, document its location with photos and notes, but leave it undisturbed. This not only prevents accidental poisoning but also helps researchers track their spread. For families or groups visiting these forests, educate children and pets about the dangers of touching or consuming wild mushrooms. Carry a first-aid kit and know the nearest medical facility, as prompt treatment (within 6–24 hours of ingestion) is critical for survival. Remember, the allure of these forests lies in their biodiversity, not in the risks posed by their most notorious resident.

Discovering Maine's Hidden Chaga: Prime Locations for Foraging Success

You may want to see also

Woodland areas in Europe and North America

The death cap mushroom, *Amanita phalloides*, thrives in woodland areas across Europe and North America, often forming symbiotic relationships with deciduous trees like oak, beech, and chestnut. These mycorrhizal associations are key to its survival, as the fungus exchanges nutrients with tree roots, ensuring both parties benefit. Foragers must be particularly cautious in these regions during late summer and autumn when death caps emerge, mimicking edible species like the straw mushroom or young puffballs. A single death cap contains enough amatoxins to cause severe liver and kidney damage, with as little as 50 grams proving fatal if ingested without immediate medical intervention.

In Europe, death caps are most prevalent in the temperate forests of France, Italy, and the United Kingdom, where they often appear after rainfall in well-drained, leafy soils. Their greenish-brown caps and white gills blend seamlessly into the forest floor, making them easy to overlook. In North America, they’ve spread aggressively in California, Oregon, and the Pacific Northwest, likely introduced via imported European trees or soil. Urban parks and residential areas with mature hardwoods are not exempt; death caps have been found in backyards and public green spaces, underscoring the need for vigilance even outside traditional woodland settings.

To avoid accidental poisoning, foragers should adhere to strict identification protocols. Key features of the death cap include a skirt-like ring on the stem, a bulbous base, and a cap that ranges from 5 to 15 cm in diameter. However, reliance on morphology alone is risky, as variations in appearance can occur. Carrying a field guide or consulting an expert is essential, and when in doubt, discard the specimen entirely. Cooking or drying does not neutralize amatoxins, and symptoms of poisoning—nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea—may not appear for 6–24 hours, delaying critical treatment.

Comparatively, while death caps are more common in Europe, their North American presence is growing due to ecological disruption and climate change. Warmer winters and altered rainfall patterns favor their mycelial networks, allowing them to outcompete native fungi. This shift highlights the importance of regional awareness; what was once a European concern is now a transatlantic threat. Foraging courses and local mycological societies offer invaluable education, emphasizing not just identification but also the ecological role of fungi in woodland ecosystems.

Finally, a persuasive argument for caution: the allure of woodland foraging should never outweigh the risk of encountering a death cap. While edible mushrooms like chanterelles and porcini also inhabit these areas, the consequences of misidentification are dire. Parents and pet owners must be especially vigilant, as children and animals are naturally curious and less discerning. By prioritizing safety over spontaneity, foragers can enjoy the bounty of Europe and North America’s woodlands without endangering themselves or their loved ones.

Discover Georgia's Best Chanterelle Mushroom Foraging Spots and Tips

You may want to see also

Lawns, parks, and gardens near trees

The death cap mushroom, or *Amanita phalloides*, has a sinister reputation as one of the most poisonous fungi in the world. Surprisingly, it doesn’t lurk in remote forests but often thrives in places humans frequent: lawns, parks, and gardens near trees. These environments mimic its native woodland habitat, providing the shade, moisture, and organic matter it needs to grow. What makes this particularly alarming is how easily it blends into its surroundings, often mistaken for edible species like the paddy straw mushroom. Its preference for tree roots, particularly oaks, beeches, and chestnuts, means any green space with these trees is a potential hotspot.

For homeowners and gardeners, understanding this habitat is crucial. The death cap forms symbiotic relationships with tree roots, absorbing nutrients while helping the tree in return. This mycorrhizal bond explains why it’s so common near trees, even in urban areas. If you have a garden with mature trees, especially those in the Fagaceae family, inspect the soil regularly during late summer and fall, its peak growing season. Look for the telltale signs: a greenish cap, white gills, and a bulbous base with a cup-like volva. Remember, even a small bite contains enough amatoxins to cause severe liver and kidney damage, so identification accuracy is non-negotiable.

Parks and public green spaces are equally at risk, particularly those with older trees and undisturbed soil. Unlike forests, these areas often see heavy foot traffic, increasing the chance of accidental contact. Parents should caution children against touching or picking mushrooms, as the death cap’s shiny cap can appear deceptively attractive. Dogs are also at risk, as they may ingest fragments while sniffing the ground. If you suspect a death cap in a public area, notify local authorities immediately—removal by professionals is essential to prevent harm.

Comparing the death cap’s presence in lawns versus wilder areas highlights a critical point: human activity can inadvertently encourage its growth. Mulching, watering, and fertilizing lawns near trees create ideal conditions for this fungus. While these practices benefit garden plants, they also favor the death cap’s mycelium. To mitigate this, avoid over-mulching and ensure proper drainage to reduce moisture retention. If you’re a forager, treat any mushroom found near trees with extreme skepticism—even experts can misidentify the death cap under certain conditions.

In conclusion, lawns, parks, and gardens near trees are not just scenic spots but potential habitats for the deadly *Amanita phalloides*. Awareness and vigilance are your best defenses. Regularly inspect these areas, especially during late summer and fall, and educate others about the risks. While the death cap’s presence is unsettling, understanding its ecology empowers you to coexist safely with this silent predator in your own backyard.

Discover Campbell's Mushroom Gravy: Top Stores and Online Retailers

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Moist, shady environments with decaying wood

Death cap mushrooms (Amanita phalloides) thrive in environments that mimic their native European habitats, which are often characterized by moist, shady areas rich in decaying wood. These conditions are not just coincidental but are essential for their mycorrhizal relationship with trees, particularly oaks, beeches, and pines. The decaying wood serves as a nutrient reservoir, while the shade and moisture create a microclimate that supports the delicate balance required for their growth. For foragers, understanding this habitat is crucial—not for finding them, but for avoiding accidental encounters, as death caps are notoriously toxic.

To identify such environments, look for wooded areas with a thick layer of leaf litter and fallen branches. These spots retain moisture longer, especially after rainfall, creating the damp conditions death caps favor. Shady areas, such as those under dense canopies or on north-facing slopes, further reduce evaporation, keeping the soil consistently humid. If you notice trees with signs of decay or stumps covered in moss, you’re in prime territory. However, exercise extreme caution: disturbing these areas could expose hidden fungi, and misidentification can be fatal.

From a comparative perspective, death caps share their habitat with many edible mushrooms, such as chanterelles and porcini, which also prefer similar conditions. The key difference lies in their appearance and ecological role. While edible species often have distinct features like gills or pores, death caps mimic harmless varieties like the straw mushroom or young puffballs. This similarity underscores the importance of habitat awareness—knowing where death caps grow can prevent tragic mistakes. For instance, a study in the Pacific Northwest found that 90% of death cap sightings were within 10 meters of decaying oak or pine wood, a statistic that highlights their habitat specificity.

For those instructing others on mushroom safety, emphasize the following: avoid picking mushrooms near decaying wood in shady, moist areas, especially if oaks or beeches are present. If you’re a homeowner with such trees, regularly inspect your yard after wet weather, as death caps can sprout unexpectedly. Compost piles or mulched areas near trees are also risk zones. For foragers, carry a field guide and a knife—cut the mushroom at the base to examine its bulbous base and volva, key identifiers of death caps. Remember, no culinary benefit outweighs the risk of consuming even a small amount of this deadly fungus.

Finally, a descriptive approach can help illustrate the danger: imagine a forest floor blanketed with fallen leaves, where sunlight barely penetrates and the air feels cool and damp. A rotting log, covered in moss and lichen, lies nearby, its wood softening into the earth. This is the death cap’s sanctuary, a place where life and decay coexist in precarious balance. While it’s a beautiful ecosystem, it’s also a reminder that nature’s most lethal creations often hide in its most serene settings. Recognizing this habitat is not just a skill—it’s a survival tactic.

Discover Cavern Mushrooms in Palworld: Top Locations to Explore

You may want to see also

Seasonal appearances in fall and spring

The death cap mushroom, *Amanita phalloides*, is a master of seasonal timing, favoring both fall and spring for its appearances. In temperate regions, particularly across Europe and North America, these toxic fungi emerge with the cooler, moist conditions that follow summer’s heat. Fall fruiting typically peaks from late September through November, coinciding with the decay of leaf litter and the increased humidity that supports mycelial growth. Spring flushes, though less prolific, occur in milder climates or higher elevations, often from March to May, as soil temperatures rise and moisture remains abundant. Understanding these windows is critical for foragers, as the death cap’s seasonal predictability increases the risk of accidental encounters during prime mushroom-hunting months.

Analyzing the environmental cues behind these appearances reveals a fungus finely tuned to its ecosystem. Death caps thrive in symbiotic relationships with deciduous and coniferous trees, particularly oak, beech, and pine. In fall, the breakdown of organic matter provides nutrients, while spring’s new growth offers fresh opportunities for mycorrhizal associations. Temperature plays a key role: mycelium remains dormant in extreme heat or cold, activating when soil temperatures range between 10°C and 18°C (50°F–65°F). Rainfall is equally crucial; a 24–48-hour period of consistent moisture often precedes fruiting bodies breaking through the soil. Foraging during these conditions without proper identification skills is akin to playing a deadly game of chance.

For those venturing into mushroom-rich areas, practical precautions are non-negotiable. In fall, avoid collecting near tree bases or in areas with heavy leaf cover, where death caps often cluster. Spring foragers should scrutinize woodland edges and newly cleared areas, where soil disturbance can trigger growth. Carry a field guide or use a verified identification app, focusing on the death cap’s distinctive features: a pale green to yellowish cap, white gills, and a bulbous base with a cup-like volva. Never consume a wild mushroom without 100% certainty of its identity, as even a small bite of *Amanita phalloides* contains enough amatoxins to cause liver failure within 48–72 hours.

Comparing fall and spring appearances highlights subtle differences in habitat and form. Fall specimens tend to be larger and more robust, benefiting from months of mycelial development, while spring mushrooms may appear smaller and more scattered. In regions with Mediterranean climates, spring flushes can rival fall in abundance, whereas colder areas may see negligible spring growth. This variability underscores the importance of local knowledge: what holds true in California’s oak woodlands differs from Germany’s beech forests. Seasonal awareness, combined with regional insights, transforms a hazardous pursuit into a safer, more informed practice.

Finally, a persuasive argument for education over eradication: rather than fearing these seasons, embrace them as opportunities to learn. Workshops, guided forays, and mycological societies offer hands-on training to distinguish death caps from edible lookalikes like *Agaricus* species. Children as young as 8 can be taught basic identification principles, while adults should focus on advanced traits like spore prints and microscopic features. By demystifying seasonal patterns, we shift from avoidance to appreciation, ensuring that fall and spring remain times of wonder, not warning, in the natural world.

Discovering Billson Mushrooms: Top Locations for Foraging Success

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Death cap mushrooms (*Amanita phalloides*) are commonly found in Europe, North America, and parts of Asia, often growing under or near trees like oaks, beeches, and pines in wooded areas.

Yes, death caps can appear in urban parks, gardens, and yards, especially where trees like oaks or chestnuts are present, as they form symbiotic relationships with these trees.

While they prefer wooded areas, death caps can occasionally be found in grassy fields near trees, as they rely on tree roots for growth.

Death caps typically appear in late summer to fall (August to November) in temperate regions, though this can vary depending on climate and location.

No, death caps are highly toxic and should never be sold in stores. However, accidental contamination of wild mushroom harvests has occurred, so always verify the source of mushrooms you consume.