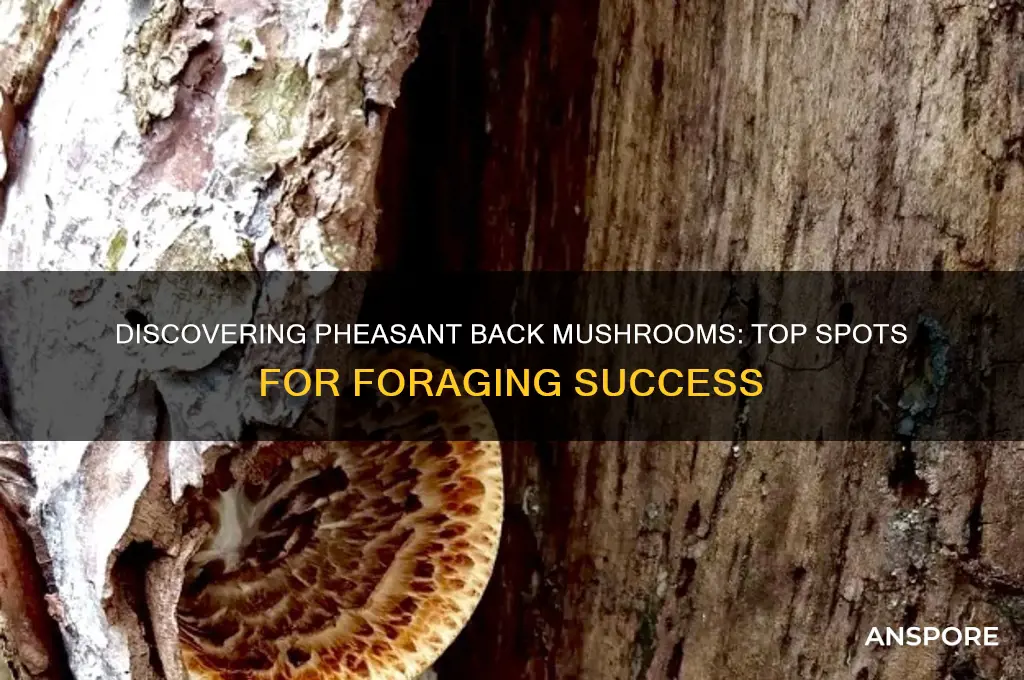

The pheasant back mushroom, scientifically known as *Polyporus arcularius*, is a fascinating and edible fungus that thrives in temperate forests across the Northern Hemisphere. To find these mushrooms, enthusiasts should focus on deciduous woodlands, particularly where oak, beech, and maple trees dominate, as they often grow on decaying wood or at the base of these trees. Look for them in the late summer to early winter months, when conditions are cool and damp, favoring their growth. They are typically found in clusters or singly, with their distinctive fan-shaped caps and wavy edges resembling the tail feathers of a pheasant, making them relatively easy to identify once you know what to look for. Always ensure proper identification before foraging, as some mushrooms can be toxic.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Scientific Name | Cerioporus squamosus (formerly Polyporus squamosus) |

| Common Names | Pheasant Back Mushroom, Dryad's Saddle, Scale-capped Polypore |

| Habitat | Deciduous and mixed forests, especially under oak, beech, and maple trees |

| Substrate | Grows on living or dead hardwood trees, stumps, and logs |

| Geographic Distribution | Widespread in North America, Europe, and Asia |

| Season | Spring to early summer (March to June in temperate regions) |

| Preferred Soil Type | Moist, well-drained soil rich in organic matter |

| Altitude | Commonly found at low to mid-elevations |

| Climate | Temperate climates with moderate humidity |

| Associated Trees | Oak, beech, maple, birch, and other hardwoods |

| Growth Form | Bracket-like or fan-shaped, often in clusters or tiers |

| Spores | White to yellowish, released from pores on the underside |

| Edibility | Young specimens are edible when cooked; older ones become tough |

| Look-Alikes | Polyporus arcularius (not toxic but less desirable) |

| Conservation Status | Not considered threatened; common in suitable habitats |

| Foraging Tips | Look for fan-shaped caps with brown, scaly surfaces near hardwood trees |

Explore related products

$19.99 $21.99

What You'll Learn

Forests with deciduous trees

Deciduous forests, with their vibrant autumn displays and rich, organic soil, provide an ideal habitat for the pheasant back mushroom (*Stropharia rugosoannulata*). These woodlands, characterized by trees that shed their leaves annually, create a dynamic ecosystem where moisture and decaying matter foster fungal growth. The key to finding pheasant back mushrooms here lies in understanding the symbiotic relationship between the forest floor and the mushroom’s lifecycle. Look for areas with abundant leaf litter, fallen branches, and well-drained soil, as these conditions mimic the mushroom’s preferred environment.

To maximize your chances, focus on deciduous forests with a mix of oak, beech, and maple trees, as their leaf decomposition enriches the soil with nutrients essential for mushroom growth. Early fall, after the first rains, is prime time for foraging, as the cooler temperatures and increased humidity trigger fruiting. Carry a small trowel to gently dig around the base of trees, where mycelium often thrives, and avoid over-harvesting to ensure the mushroom population remains sustainable.

A comparative analysis of deciduous forests versus coniferous ones reveals why the former is superior for pheasant back mushrooms. Coniferous forests, with their acidic, needle-based soil, lack the pH balance and organic diversity that deciduous forests offer. Additionally, the shade provided by deciduous trees in summer and the sunlight that reaches the forest floor in winter create a microclimate conducive to fungal development. This contrast highlights the importance of habitat specificity in mushroom foraging.

Foraging in deciduous forests requires caution. Always carry a field guide or use a reliable mushroom identification app to avoid toxic look-alikes, such as the poisonous *Amanita* species. Wear gloves and long sleeves to protect against ticks and thorns, and never consume a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity. If you’re new to foraging, consider joining a local mycological society or hiring a guide to learn the nuances of safe and sustainable harvesting.

In conclusion, deciduous forests are a treasure trove for pheasant back mushroom enthusiasts, offering the perfect blend of environmental conditions for their growth. By understanding the forest’s ecology, timing your search, and practicing responsible foraging, you can enjoy the rewards of this delectable mushroom while preserving its natural habitat for future seasons.

Discover Hidden Spots to Find Morale Mushrooms in Nature

You may want to see also

Wooded areas after rain

After a soaking rain, the forest floor transforms into a fertile hunting ground for the elusive pheasant back mushroom (*Pheasant back mushroom*, or *Polyporus arcularius*). The moisture awakens dormant mycelium, triggering fruiting bodies to push through the damp duff. Look for them nestled at the base of deciduous trees, particularly oak and beech, where their bracket-like caps blend seamlessly with fallen leaves and twigs. Their earthy brown hues, often streaked with darker zones, mimic the forest’s palette, making them both a challenge and a reward to spot.

To maximize your chances, time your foray 2–3 days after a significant rainfall, when the soil retains enough moisture to sustain growth but isn’t waterlogged. Carry a small trowel to gently lift leaf litter without damaging the delicate stems. Avoid areas with heavy foot traffic, as these mushrooms prefer undisturbed habitats. Early morning or late afternoon light enhances visibility, casting shadows that highlight their distinctive fan-shaped caps.

Comparatively, while other mushrooms like chanterelles thrive in drier, mossy environments, pheasant backs are rain-dependent opportunists. Their preference for post-rain conditions makes them a seasonal find, typically emerging in late spring through early autumn. Unlike morels, which require fire-scarred landscapes, pheasant backs favor the quiet, shaded understory of mature woodlands. This specificity underscores the importance of understanding their ecological niche for successful foraging.

Foraging ethically is paramount. Harvest only what you need, leaving some mushrooms to release spores and ensure future growth. Avoid picking near roadsides due to potential contamination from runoff. Always carry a field guide or use a reliable app to confirm identification, as look-alikes like the bitter *Trametes versicolor* lack the pheasant back’s distinct texture and flavor. With patience and respect for their habitat, these rain-loving mushrooms reward the observant forager with their nutty, meaty essence.

Discover Hidden Iron Mushroom Locations in TotK: Ultimate Guide

You may want to see also

Near oak, beech, or chestnut trees

Pheasant back mushrooms, scientifically known as *Polyporus umbellatus*, have a distinct preference for certain tree species, particularly oak, beech, and chestnut. These trees are not just coincidental neighbors but essential partners in the mushroom’s lifecycle. Oak trees, with their robust root systems and rich organic matter, provide an ideal substrate for mycelial growth. Beech trees, known for their dense canopies and acidic leaf litter, create a microclimate that retains moisture—a critical factor for mushroom fruiting. Chestnut trees, though less common in some regions, offer similar benefits, especially in areas where they thrive. Understanding this symbiotic relationship is key to locating these mushrooms in the wild.

To maximize your chances of finding pheasant back mushrooms, focus on mature stands of oak, beech, or chestnut trees, particularly in deciduous forests. Look for areas where leaf litter has accumulated over time, forming a thick, nutrient-rich layer. The mushrooms often appear in clusters at the base of these trees, especially after periods of rain. A practical tip: bring a small trowel to gently lift the leaf litter, as the mushrooms can be partially buried. Avoid trampling the area, as this can damage the mycelium and reduce future fruiting.

Comparatively, while pheasant back mushrooms can occasionally be found near other hardwoods, their affinity for oak, beech, and chestnut is unparalleled. For instance, studies have shown that oak-dominated forests yield significantly higher populations of these mushrooms compared to maple or hickory forests. Beech forests, though less common, are particularly promising in regions like Eastern Europe and parts of North America. Chestnut trees, once abundant but now scarcer due to blight, still support pheasant back mushrooms in areas where they have been reintroduced or naturally persist.

A persuasive argument for focusing on these tree species lies in their ecological role. Oak, beech, and chestnut trees are foundational species in many temperate forests, shaping the soil composition and understory vegetation. Their presence indicates a healthy, stable ecosystem—prime conditions for pheasant back mushrooms. By targeting these trees, foragers not only increase their success rate but also contribute to the conservation of these vital forest habitats. Remember, sustainable foraging practices, such as leaving some mushrooms to spore and avoiding overharvesting, ensure these ecosystems remain productive for future seasons.

Finally, a descriptive note: imagine a late autumn morning, the forest floor blanketed with golden oak leaves or the coppery hues of beech. The air is crisp, and the scent of damp earth fills your lungs. At the base of a towering oak, partially concealed by moss and leaf litter, you spot a cluster of pheasant back mushrooms—their fan-shaped caps and velvety texture standing out against the forest floor. This is the reward for understanding the mushroom’s preference for these specific trees. With patience and observation, you’ll learn to recognize the subtle signs that signal their presence, turning each foraging trip into a rewarding exploration of nature’s intricacies.

Sydney's Secret Spots: Discovering Magic Mushrooms in Nature

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Disturbed soil or wood chips

Pheasant back mushrooms, scientifically known as *Polyporus arcularius*, thrive in environments where the soil or wood has been disrupted. This disturbance creates the ideal conditions for their growth, making them a fascinating subject for foragers and mycologists alike. Understanding where and how these disturbances occur can significantly increase your chances of finding this elusive mushroom.

Analytical Insight: Disturbed soil or wood chips often result from human activities such as construction, gardening, or landscaping. These actions expose the underlying substrate to air and light, creating microenvironments that pheasant back mushrooms favor. For instance, freshly mulched garden beds or areas where trees have been removed are prime locations. The fungi colonize the exposed wood chips or soil, breaking down organic matter and forming their distinctive fan-shaped caps. This symbiotic relationship between disturbance and fungal growth highlights the adaptability of *Polyporus arcularius*.

Instructive Guide: To maximize your chances of finding pheasant back mushrooms, focus on areas with recent disturbances. Look for parks or yards where wood chip mulch has been laid within the past year, as older mulch may have already been colonized by other fungi. Similarly, construction sites or trails with exposed soil are worth exploring. Bring a small trowel to gently dig around the base of trees or in wood chip piles, as the mushrooms often grow in clusters. Avoid areas treated with pesticides or chemical fertilizers, as these can inhibit fungal growth.

Comparative Perspective: Unlike mushrooms that prefer undisturbed, mature forests, pheasant backs are opportunistic. They capitalize on the nutrients released by disturbed wood or soil, setting them apart from species like chanterelles or morels. This preference for disruption makes them more accessible to urban foragers, as they can often be found in city parks or suburban gardens. However, their reliance on disturbed environments also means their populations can be transient, appearing one season and vanishing the next if the area returns to stability.

Practical Tips: When foraging in disturbed areas, wear gloves to protect your hands from debris and potential irritants. Keep a field guide or mushroom identification app handy to ensure you’re correctly identifying pheasant backs, as they can resemble other species. Harvest sustainably by leaving some mushrooms to release spores and perpetuate the colony. Finally, always ask for permission when foraging on private property, and respect local regulations regarding mushroom collection in public spaces.

Descriptive Takeaway: Picture a freshly mulched garden path, the wood chips still fragrant with the scent of pine or cedar. Beneath the surface, a network of mycelium is at work, and soon, delicate pheasant back mushrooms will emerge, their caps a warm brown with a hint of gray. This scene encapsulates the beauty of finding these fungi in disturbed areas—a reminder that even in disruption, nature finds a way to thrive. By understanding and appreciating this process, you’ll not only locate pheasant back mushrooms but also gain a deeper connection to the ecosystems around you.

Discovering Hen of the Woods Mushrooms in Connecticut's Forests

You may want to see also

Fall in temperate climates

To maximize your chances, focus on areas with rich, well-drained soil and partial shade. Pheasant backs often appear in clusters, their distinctive brown caps and thick, grooved stems standing out against the forest floor. A pro tip: bring a basket rather than a plastic bag to allow spores to disperse as you forage, ensuring future growth. Avoid overharvesting by leaving at least one mature mushroom per patch. While they’re edible and prized for their meaty texture, always confirm identification—their resemblance to toxic look-alikes like the manure mushroom (*Stropharia coronilla*) makes a field guide or expert consultation essential.

Comparatively, fall foraging for pheasant backs differs from summer hunts due to the shift in fungal activity. Summer mushrooms, like chanterelles, prefer drier conditions and often grow in more open areas. In contrast, fall’s cooler, wetter environment encourages mycelial growth in denser, shadier spots. This seasonal shift also means fewer insects competing for the mushrooms, though slugs remain a persistent foe. To outsmart them, arrive early in the morning when mushrooms are freshest and slugs less active.

For the home cultivator, fall offers a unique opportunity to inoculate outdoor beds with pheasant back spawn. Prepare a mixture of straw and compost, bury it in a shaded area, and introduce the mycelium. Keep the bed consistently moist, and by the following fall, you may harvest your own crop. This method mimics their natural habitat, ensuring higher yields than indoor cultivation. However, be patient—mycelial colonization takes time, and fruiting depends on environmental cues like temperature and humidity.

In essence, fall in temperate climates is not just a season but a window of opportunity for pheasant back enthusiasts. Whether foraging or cultivating, understanding the interplay of soil, weather, and timing is key. With careful observation and respect for the ecosystem, this season rewards both the novice and the seasoned forager alike.

Discovering Indigo Milk Cap Mushrooms: Top Locations and Foraging Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Pheasant back mushrooms (Stropharia rugosoannulata) thrive in rich, moist soil, often near compost piles, wood chips, or well-rotted manure. They are commonly found in gardens, parks, and agricultural areas.

Pheasant back mushrooms are most commonly found in late summer to early fall, though they can also appear in spring under the right conditions.

Pheasant back mushrooms can be cultivated in gardens or on mushroom beds using compost or wood chips. They are a popular choice for home growers due to their robust flavor and ease of cultivation.

Pheasant back mushrooms are relatively easy to identify by their large, brown-capped fruiting bodies with distinctive scales. However, they can be confused with toxic species like the manure fungus (Coprinus comatus) or young Amanita species. Always consult a field guide or expert if unsure.