Mushrooms that grow on dead trees, often referred to as saprotrophic or wood-decay fungi, play a crucial role in forest ecosystems by breaking down decaying wood and recycling nutrients. These fungi thrive on the cellulose and lignin found in dead or dying trees, transforming them into rich organic matter. Common examples include oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), which are prized for their culinary value, and turkey tail (*Trametes versicolor*), known for its medicinal properties. Other species like the artist's conk (*Ganoderma applanatum*) and reishi (*Ganoderma lucidum*) also colonize dead wood, contributing to both ecological balance and human uses. Understanding which mushrooms grow on dead trees not only highlights their ecological importance but also offers insights into sustainable practices, such as mushroom cultivation and forest management.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Oyster Mushrooms: Thrive on decaying wood, breaking down lignin, and are commonly found on dead trees

- Shiitake Mushrooms: Prefer hardwood logs, often cultivated on dead oak or beech trees

- Reishi Mushrooms: Grow on decaying trees, known for medicinal properties and woody texture

- Turkey Tail Mushrooms: Common on dead or dying trees, aiding in wood decomposition and immune support

- Chaga Mushrooms: Parasitize birch trees, forming black masses on dead or weakened trunks

Oyster Mushrooms: Thrive on decaying wood, breaking down lignin, and are commonly found on dead trees

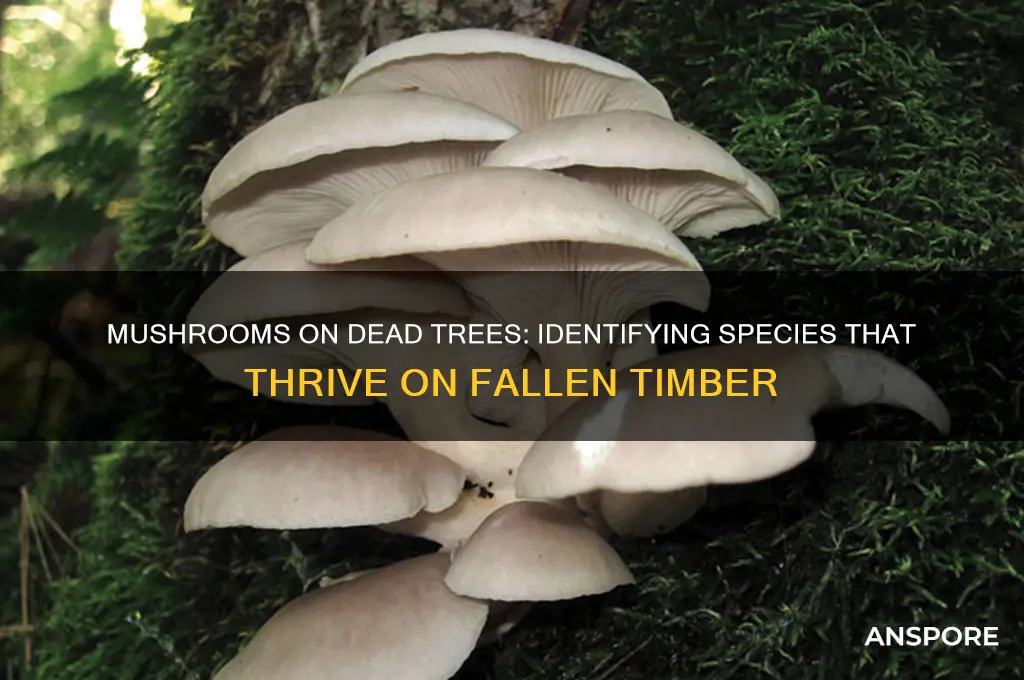

Oyster mushrooms, scientifically known as *Pleurotus ostreatus*, are nature’s recyclers, thriving on decaying wood by breaking down lignin, a complex polymer found in plant cell walls. This ability makes them not only ecologically vital but also a prime example of fungi that flourish on dead trees. Their role in decomposing wood accelerates nutrient cycling in forests, returning essential elements to the soil. For foragers and cultivators, identifying these mushrooms is straightforward: their fan-shaped caps, ranging from gray to brown, often cluster on fallen logs or standing deadwood. This symbiotic relationship between oyster mushrooms and dead trees highlights their adaptability and importance in both wild ecosystems and human cultivation.

To cultivate oyster mushrooms on dead trees or wood, follow these steps: first, source hardwood logs or wood chips from trees like beech, oak, or poplar, ensuring they are free from chemicals. Next, inoculate the wood with oyster mushroom spawn, drilling small holes for plug spawn or layering sawdust spawn in wood chip beds. Keep the environment humid (70-90% humidity) and maintain temperatures between 55-75°F (13-24°C). Within 4-6 weeks, mycelium will colonize the wood, and fruiting bodies will appear after exposing the logs to cooler, fresher air. Harvest mushrooms when the caps are still convex, as they’ll have a firmer texture and milder flavor. This process not only yields a nutritious food source but also repurposes dead wood sustainably.

Comparatively, oyster mushrooms stand out among wood-decomposing fungi due to their rapid growth and high yield. Unlike shiitake mushrooms, which prefer oak and take longer to fruit, oyster mushrooms are less selective and can colonize a wider range of wood types. Their ability to break down lignin efficiently also surpasses many other species, making them ideal for mycoremediation—using fungi to degrade pollutants in wood or soil. This versatility, combined with their culinary appeal, explains their popularity in both commercial and home cultivation settings.

Foraging for oyster mushrooms on dead trees requires caution. Always identify them confidently, as some toxic look-alikes, like the olive-colored *Omphalotus olearius*, grow in similar habitats. Carry a field guide or use a reliable app for verification. Harvest sustainably by cutting the mushrooms at the base, leaving enough to regrow and minimizing damage to the mycelium. Avoid collecting near roadsides or industrial areas, where wood may be contaminated. Properly cleaned and cooked, oyster mushrooms offer a delicate, anise-like flavor and are rich in protein, vitamins, and antioxidants, making them a rewarding find for both palate and health.

Using Fogue Mushrooms in Animal Parade: Safe Food Options Explored

You may want to see also

Shiitake Mushrooms: Prefer hardwood logs, often cultivated on dead oak or beech trees

Shiitake mushrooms (Lentinula edodes) are a prime example of fungi that thrive on dead hardwood, particularly oak and beech trees. This preference isn’t arbitrary; hardwood logs provide the dense, nutrient-rich substrate shiitakes need to grow. Unlike softwoods, which often lack sufficient lignin and cellulose, hardwoods offer a durable environment that supports mushroom colonization over multiple years. For cultivators, selecting the right wood type is critical—oak and beech are ideal due to their structure and longevity, ensuring a steady yield for up to 5–7 years.

To cultivate shiitakes on dead trees, start by sourcing freshly cut hardwood logs, 3–6 inches in diameter and 3–4 feet long. Drill holes 1.5 inches deep and 5–6 inches apart, then insert shiitake spawn plugs into each hole. Seal the plugs with wax to retain moisture and prevent contamination. Stack the logs in a shaded, humid area, ensuring they remain damp but not waterlogged. Mist the logs periodically, especially during dry periods, to mimic the natural forest environment. Harvest begins 6–12 months after inoculation, with subsequent flushes occurring every 8–12 weeks under optimal conditions.

Comparatively, shiitakes outperform many other mushrooms in terms of yield and adaptability to hardwood substrates. While oyster mushrooms grow faster, they often exhaust their substrate in a single season. Shiitakes, however, produce multiple flushes annually, making them a more sustainable choice for long-term cultivation. Their ability to break down hardwood lignin also contributes to forest ecosystem health, recycling nutrients back into the soil. This dual benefit—high yield and ecological impact—positions shiitakes as a top choice for both commercial growers and hobbyists.

For those new to shiitake cultivation, start small with 10–20 logs to gauge success before scaling up. Avoid using wood treated with pesticides or chemicals, as these can harm the mycelium. Monitor logs for signs of contamination, such as green mold, and remove affected areas promptly. Pairing shiitake cultivation with other hardwood-loving species, like reishi or lion’s mane, can maximize log usage and diversify your harvest. With patience and attention to detail, dead oak or beech trees can transform into a bountiful source of shiitakes, blending productivity with sustainability.

Brewing Magic Mushrooms: Exploring the Possibilities and Risks

You may want to see also

Reishi Mushrooms: Grow on decaying trees, known for medicinal properties and woody texture

Reishi mushrooms, scientifically known as *Ganoderma lucidum*, are a prime example of fungi that thrive on decaying trees, particularly hardwoods like oak and maple. Their preference for dead or dying wood is not just a quirk of nature but a strategic adaptation. By breaking down lignin, a complex polymer in wood, Reishis play a vital role in nutrient recycling within forest ecosystems. This symbiotic relationship highlights their ecological importance, but it’s their medicinal properties that have captured human interest for millennia.

From a practical standpoint, cultivating Reishi mushrooms at home is feasible but requires patience and specific conditions. Start by sourcing hardwood logs or stumps, ensuring they are freshly cut or in the early stages of decay. Inoculate the wood with Reishi spawn, available from specialty suppliers, and keep it in a humid, shaded environment. The process can take 6–12 months, but the payoff is a sustainable supply of these medicinal fungi. For those less inclined to cultivate, dried Reishi slices or extracts are widely available, with dosages typically ranging from 1–1.5 grams per day for adults, though consulting a healthcare provider is advised.

Comparatively, Reishi stands out among medicinal mushrooms for its woody texture and bitter taste, which often make it less palatable for direct consumption. Unlike the meaty Lion’s Mane or the versatile Chaga, Reishi is rarely used in culinary applications. Instead, its bioactive compounds, such as triterpenes and polysaccharides, are extracted into teas, tinctures, or capsules. This distinction underscores its role as a functional rather than a culinary mushroom, prized for immune support, stress reduction, and potential anti-inflammatory effects.

Descriptively, Reishi mushrooms are a sight to behold, with their kidney-shaped caps and glossy, lacquer-like surfaces ranging from deep red to brown. Their tough, fibrous texture is a testament to their resilience, both in the wild and in the human body. Foraging for Reishi in nature requires a keen eye, as they often blend into the bark of decaying trees. However, their distinctive appearance and lack of gills make them relatively easy to identify once spotted.

In conclusion, Reishi mushrooms exemplify the intersection of ecology and wellness, thriving on dead trees while offering profound health benefits. Whether cultivated, foraged, or purchased, their unique properties make them a valuable addition to any medicinal regimen. By understanding their growth habits and practical applications, enthusiasts can harness the power of Reishi to support both personal health and environmental sustainability.

Exploring Mushrooms' Potential Benefits for Managing ADHD Symptoms Naturally

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Turkey Tail Mushrooms: Common on dead or dying trees, aiding in wood decomposition and immune support

Dead and dying trees, often seen as mere remnants of a forest's past, are in fact bustling hubs of biological activity, thanks in part to fungi like the Turkey Tail mushroom (*Trametes versicolor*). These fan-shaped, multicolayered mushrooms are a common sight on decaying wood, where they play a dual role: breaking down lignin and cellulose in trees, and offering potential health benefits to humans. Their ability to thrive on dead trees is a testament to nature’s recycling system, where decomposition is not an end but a transformation.

From a practical standpoint, Turkey Tail mushrooms are not just ecologically significant but also medicinally valuable. Studies have shown that their extracts, particularly polysaccharide-K (PSK) and polysaccharide-peptide (PSP), can enhance immune function. For instance, PSK is approved in Japan as an adjuvant cancer therapy, often prescribed alongside chemotherapy to mitigate side effects and boost immunity. A typical dosage for immune support is 2–3 grams of Turkey Tail extract daily, though consultation with a healthcare provider is essential, especially for those with pre-existing conditions. This fungus bridges the gap between forest ecology and human health, turning a decomposer into a healer.

Comparatively, while other mushrooms like Oyster (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) and Shiitake (*Lentinula edodes*) also grow on dead trees, Turkey Tail stands out for its resilience and medicinal potency. Unlike the culinary appeal of its counterparts, Turkey Tail’s value lies in its bioactive compounds, which have been studied for their antiviral, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant properties. Its adaptability to various tree species—beech, oak, or maple—further underscores its role as a universal decomposer and a versatile medicinal resource.

Foraging for Turkey Tail mushrooms requires caution, as their appearance can be mimicked by toxic species like the False Turkey Tail (*Stereum ostrea*). Key identifiers include their zoned cap colors (brown, tan, and white) and underside pores. Once identified, they can be harvested sustainably by cutting the base, leaving enough for regrowth. For those interested in their immune-boosting properties, commercially available extracts or teas are a safer, more controlled option. Whether in the forest or the pharmacy, Turkey Tail mushrooms exemplify the interconnectedness of ecosystems and human well-being.

Snorting Mushrooms: Risks, Effects, and Why It’s Not Recommended

You may want to see also

Chaga Mushrooms: Parasitize birch trees, forming black masses on dead or weakened trunks

In the heart of boreal forests, where birch trees stand as silent sentinels, Chaga mushrooms (Inonotus obliquus) emerge as a striking anomaly. Unlike the vibrant caps of shiitake or oyster mushrooms, Chaga manifests as a black, charcoal-like mass, often likened to a clump of burnt wood. This fungus is a parasite, specifically targeting birch trees, though it rarely kills its host outright. Instead, it thrives on dead or weakened trunks, drawing nutrients from the decaying wood. Its slow growth—often taking 10 to 20 years to mature—makes it a rare and prized find for foragers.

From a practical standpoint, harvesting Chaga requires both precision and respect for the ecosystem. Use a sharp knife to cut the mushroom from the tree, leaving at least one-third of the growth intact to allow for regrowth. Avoid harvesting from trees that appear healthy or from areas where Chaga is scarce. Once collected, the mushroom can be processed into a potent tea or tincture. To prepare tea, break a walnut-sized piece into smaller chunks, simmer in water for 4–6 hours, and strain. For a tincture, steep Chaga in alcohol (such as vodka) for 6–8 weeks, shaking occasionally. Dosage varies, but starting with 1–2 cups of tea daily or 1–2 droppers of tincture is common, though consulting a healthcare provider is advised, especially for those on medication.

Comparatively, Chaga stands apart from other mushrooms that grow on dead trees, like oyster or lion’s mane, due to its unique composition and medicinal properties. Rich in betulinic acid, melanin, and antioxidants, it has been used in traditional medicine for centuries, particularly in Siberia and Northern Europe, to boost immunity and reduce inflammation. Studies suggest its potential in supporting cancer treatment, though research is still in early stages. Unlike edible mushrooms, Chaga is not consumed directly due to its hard, woody texture, making extraction methods essential for harnessing its benefits.

Descriptively, encountering Chaga in the wild is akin to discovering a piece of the forest’s hidden alchemy. Its rough, cracked exterior contrasts with the smooth bark of the birch, creating a visual dialogue between life and decay. The mushroom’s interior, however, reveals a rust-colored layer, a testament to its vitality within the decaying host. This duality—a parasite that both consumes and preserves—underscores Chaga’s role in the forest ecosystem, breaking down dead wood to return nutrients to the soil while offering medicinal value to humans.

In conclusion, Chaga mushrooms exemplify the intricate relationship between fungi and their environment, particularly in their parasitic yet symbiotic bond with birch trees. For foragers and herbalists, understanding its growth patterns, harvesting ethically, and preparing it correctly unlocks its potential as a natural remedy. Whether steeped in a warming tea or extracted into a tincture, Chaga bridges the gap between forest and wellness, a reminder of nature’s resilience and resourcefulness.

Breastfeeding and Mushrooms: Safe or Risky for Nursing Moms?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mushrooms that commonly grow on dead trees include oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), turkey tail (*Trametes versicolor*), and shiitake mushrooms (*Lentinula edodes*). These species are saprotrophic, meaning they decompose dead wood for nutrients.

No, not all mushrooms growing on dead trees are safe to eat. While some, like oyster and shiitake mushrooms, are edible and nutritious, others, such as the deadly *Galerina marginata* or *Hypholoma fasciculare*, are toxic. Always identify mushrooms accurately before consuming.

Mushrooms that grow on dead trees are typically saprotrophic fungi, which break down dead organic matter to obtain nutrients. Living trees have defense mechanisms that prevent most fungi from colonizing them, whereas dead trees lack these defenses, making them ideal substrates for saprotrophic fungi.