Mushrooms, as fungi, lack the ability to photosynthesize like plants and instead rely on unique structures to obtain nutrients. The key structure that allows a growing mushroom to nourish itself is the mycelium, a vast network of thread-like filaments called hyphae. This mycelium extends into the substrate (such as soil, wood, or organic matter) and secretes enzymes to break down complex organic materials into simpler compounds, which are then absorbed and used for growth. The mushroom itself, often referred to as the fruiting body, is merely the reproductive structure of the fungus, while the mycelium serves as the primary means of nutrient acquisition and sustenance.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Mycelium Network: Absorbs nutrients from substrate, enabling mushroom growth

- Hyphal Tips: Penetrate organic matter to extract essential resources

- Enzymatic Breakdown: Secretes enzymes to decompose complex materials for nourishment

- Symbiotic Relationships: Forms mutualistic bonds with plants for nutrient exchange

- Water Absorption: Efficiently draws moisture to support metabolic processes

Mycelium Network: Absorbs nutrients from substrate, enabling mushroom growth

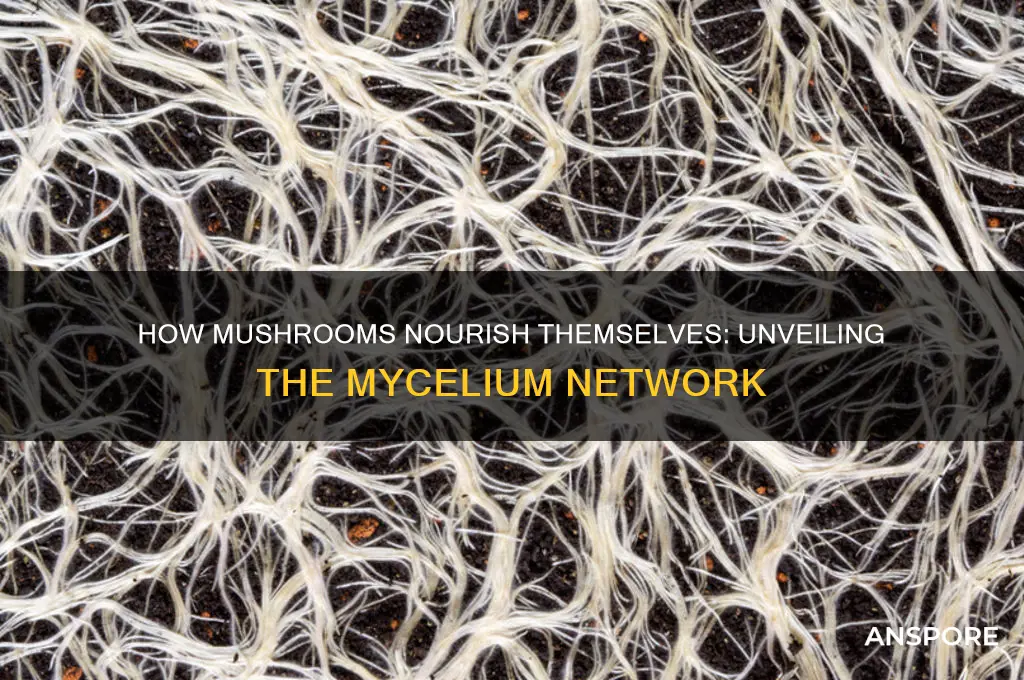

The mycelium network is the unsung hero behind the growth and sustenance of mushrooms, serving as the vital structure that enables these fungi to nourish themselves. Mycelium consists of a dense, thread-like network of cells called hyphae, which spread extensively through the substrate—the material in which the mushroom grows, such as soil, wood, or compost. This network acts as the mushroom's root system, absorbing nutrients and water essential for growth. Unlike plants, which rely on photosynthesis, mushrooms are heterotrophs, meaning they must obtain their nutrients from external sources. The mycelium network efficiently breaks down organic matter in the substrate, converting complex compounds into simpler forms that the mushroom can use for energy and development.

The process by which the mycelium network absorbs nutrients is both intricate and efficient. Hyphae secrete enzymes that decompose the substrate, breaking down cellulose, lignin, and other complex materials into smaller molecules like sugars, amino acids, and minerals. These nutrients are then absorbed directly through the cell walls of the hyphae and transported throughout the mycelium network. This ability to extract resources from diverse substrates allows mushrooms to thrive in various environments, from forest floors to decaying logs. The mycelium's expansive reach ensures that even distant nutrient sources can be tapped, providing a steady supply of nourishment for the growing mushroom.

Another critical function of the mycelium network is its role in water absorption, which is equally important for mushroom growth. Hyphae are highly efficient at drawing moisture from the substrate, ensuring that the mushroom remains hydrated. Water is essential for transporting nutrients within the mycelium and for maintaining the turgidity of the mushroom's fruiting body. The network's ability to retain and distribute water also helps the mushroom withstand periods of drought, enhancing its resilience in challenging conditions. This dual role of nutrient and water absorption underscores the mycelium's central importance in the mushroom's life cycle.

The mycelium network also facilitates communication and resource sharing among mushrooms, further supporting their growth. Through a process known as anastomosis, hyphae from different mycelial networks can fuse together, creating a shared system that allows for the exchange of nutrients and genetic material. This interconnectedness can enhance the overall health and productivity of mushroom colonies, as resources are distributed where they are most needed. Additionally, the mycelium network can store excess nutrients, providing a reserve that supports mushroom growth during times when the substrate is less fertile.

In summary, the mycelium network is the cornerstone of mushroom nourishment, enabling these fungi to absorb nutrients and water from their substrate. Its expansive, efficient, and adaptive nature ensures that mushrooms can thrive in diverse environments, making it a fascinating and essential structure in the fungal kingdom. Understanding the role of the mycelium network not only sheds light on mushroom biology but also highlights its potential applications in areas like agriculture, ecology, and biotechnology.

Outdoor Oyster Mushroom Cultivation: Simple Steps for a Bountiful Harvest

You may want to see also

Hyphal Tips: Penetrate organic matter to extract essential resources

Mushrooms, as fungi, rely on a unique and intricate network to obtain nutrients, and this process is primarily facilitated by their hyphal tips. These specialized structures are the key to a mushroom's ability to nourish itself, playing a critical role in resource acquisition. Hyphal tips are the growing ends of fungal hyphae, which are thread-like filaments that collectively form the mycelium, the vegetative part of a fungus. When a mushroom is growing, these hyphal tips are at the forefront of its survival strategy, actively seeking and penetrating organic matter to extract the essential resources required for development.

The primary function of hyphal tips is to explore and invade substrates, such as soil, wood, or decaying plant material. This invasion is a precise and controlled process. As the hyphal tip grows, it secretes enzymes that break down complex organic compounds into simpler forms that the fungus can absorb. This enzymatic activity is crucial, as it allows the mushroom to access nutrients like carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids, which are often locked within the structural components of organic matter. The hyphal tip's ability to penetrate and digest these materials is fundamental to the mushroom's nutrition.

Upon encountering a suitable substrate, the hyphal tip initiates a highly coordinated process. It begins by attaching itself to the organic matter, forming a secure foothold. This attachment is followed by the secretion of a range of hydrolytic enzymes, including cellulases, hemicellulases, and proteases, which degrade the substrate's cell walls and other complex structures. As these enzymes break down the organic material, the resulting simple sugars, amino acids, and other nutrients are then absorbed directly through the hyphal wall, providing the mushroom with the energy and building blocks necessary for growth.

The efficiency of hyphal tips in extracting resources is remarkable. They can navigate through intricate environments, such as the pores of wood or the spaces between soil particles, maximizing the surface area available for nutrient absorption. This ability to penetrate and exploit a wide variety of organic materials gives mushrooms a competitive edge in diverse ecosystems. Furthermore, the hyphal network can rapidly redistribute these acquired nutrients to other parts of the fungus, ensuring that the entire organism benefits from the resources gathered by the hyphal tips.

In summary, hyphal tips are the mushroom's primary tool for self-nourishment, enabling them to thrive in various environments. Their role in penetrating organic matter and extracting essential resources is a testament to the sophistication of fungal biology. Understanding this process not only sheds light on the unique survival strategies of mushrooms but also highlights the importance of fungi in nutrient cycling within ecosystems. By breaking down organic matter, mushrooms contribute to the decomposition process, playing a vital role in the health and sustainability of their habitats.

Are Mushroom Grow Kits Worth It? Pros, Cons, and Tips

You may want to see also

Enzymatic Breakdown: Secretes enzymes to decompose complex materials for nourishment

Mushrooms, as fungi, have evolved a unique and efficient mechanism to obtain nutrients from their environment, primarily through the process of enzymatic breakdown. Unlike plants, which can photosynthesize, mushrooms lack chlorophyll and must rely on external organic matter for sustenance. The structure that enables this process is the mycelium, a network of thread-like filaments called hyphae. The mycelium secretes a variety of enzymes into its surroundings, which break down complex organic materials such as cellulose, lignin, and chitin into simpler, absorbable nutrients. This enzymatic activity is fundamental to the mushroom's ability to nourish itself and thrive in diverse ecosystems.

The enzymatic breakdown process begins when the mycelium detects nutrients in its environment. The hyphae then secrete enzymes tailored to the specific materials present, such as cellulases for cellulose or ligninases for lignin. These enzymes act as biological catalysts, accelerating the decomposition of complex polymers into smaller molecules like sugars, amino acids, and fatty acids. This transformation is crucial because mushrooms can only absorb nutrients in their simplest forms. The efficiency of this process highlights the mushroom's adaptability and its role as a primary decomposer in ecosystems, recycling organic matter back into the environment.

One of the most remarkable aspects of enzymatic breakdown is the specificity and diversity of the enzymes produced. For example, mushrooms can secrete proteases to break down proteins, amylases to decompose starches, and lipases to hydrolyze fats. This versatility allows mushrooms to exploit a wide range of substrates, from decaying wood to soil organic matter. The enzymes are typically released extracellularly, meaning they act outside the fungal cells, and the resulting nutrients are then absorbed through the cell walls of the hyphae. This extracellular digestion is a key feature that distinguishes fungi from animals, which perform digestion internally.

The role of enzymatic breakdown extends beyond mere nourishment; it also facilitates the mushroom's ecological function as a decomposer. By breaking down complex materials like lignin, which is resistant to degradation by most organisms, mushrooms contribute significantly to nutrient cycling in ecosystems. This process not only sustains the mushroom but also enriches the soil, making essential nutrients available to other organisms. Thus, the enzymatic activity of the mycelium is a vital link in the food web, connecting dead organic matter to living organisms.

In summary, the mycelium's ability to secrete enzymes for decomposing complex materials is the cornerstone of a mushroom's survival strategy. This enzymatic breakdown process exemplifies the fungus's resourcefulness in extracting nutrients from its environment. By transforming inaccessible organic matter into usable forms, mushrooms not only nourish themselves but also play a critical role in ecosystem health. Understanding this mechanism underscores the importance of fungi in biological systems and their unique contributions to the natural world.

Growing Mushrooms in Florida: A Step-by-Step Guide for Beginners

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Symbiotic Relationships: Forms mutualistic bonds with plants for nutrient exchange

Mushrooms, as part of the fungal kingdom, have evolved remarkable strategies to nourish themselves, often forming symbiotic relationships with plants in a mutualistic bond known as mycorrhiza. This relationship is a prime example of how fungi and plants collaborate for nutrient exchange, benefiting both parties. The structure that enables this process is the mycorrhizal network, a complex web of fungal hyphae that extends into the soil and associates with plant roots. Through this network, mushrooms gain access to carbohydrates produced by the plant through photosynthesis, while the plant receives essential nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen that the fungus has extracted from the soil.

Mycorrhizal associations come in several forms, but the most common are arbuscular mycorrhizae (AM) and ectomycorrhizae (EM). In arbuscular mycorrhizae, fungal hyphae penetrate the plant’s root cells, forming tree-like structures called arbuscules, which facilitate nutrient exchange. This type of symbiosis is widespread and occurs in approximately 80% of land plants. Ectomycorrhizae, on the other hand, involve the fungus enveloping the plant root with a sheath-like structure called a mantle, while hyphae extend into the root cortex. This form is common in woody plants like trees and provides enhanced nutrient uptake, particularly in nutrient-poor soils.

The mutualistic bond between mushrooms and plants is not limited to nutrient exchange. Fungi also improve soil structure, increase water absorption, and protect plants from pathogens. For instance, fungal hyphae can act as a barrier against soil-borne diseases and produce antimicrobial compounds that safeguard the plant. In return, the plant provides the fungus with a steady supply of carbohydrates, which are essential for fungal growth and reproduction. This interdependence highlights the sophistication of symbiotic relationships in nature.

Another critical aspect of this symbiosis is the role of mushrooms in nutrient cycling. Fungi are highly efficient at breaking down organic matter and mineralizing nutrients that are otherwise inaccessible to plants. By forming mycorrhizal networks, mushrooms act as a bridge between decomposing organic material and living plants, ensuring a continuous flow of nutrients through the ecosystem. This process is particularly vital in forest ecosystems, where mycorrhizal fungi contribute significantly to the health and productivity of trees.

Understanding these symbiotic relationships has practical implications for agriculture and ecology. Farmers and gardeners can harness mycorrhizal fungi to enhance crop yields and reduce the need for chemical fertilizers. Inoculating soils with beneficial fungi can improve plant health and resilience, promoting sustainable farming practices. Moreover, studying these relationships provides insights into the intricate web of life and underscores the importance of preserving fungal biodiversity for ecosystem stability. In essence, the mycorrhizal structure is not just a means for mushrooms to nourish themselves but a cornerstone of plant-fungal cooperation that sustains life on Earth.

Mastering Mushroom Cultivation: A Guide to Growing from Spore Prints

You may want to see also

Water Absorption: Efficiently draws moisture to support metabolic processes

Mushrooms, as fungi, have evolved specialized structures to efficiently absorb water, a critical resource for their growth and metabolic processes. Unlike plants, which use roots to extract water from the soil, mushrooms rely on a network of thread-like structures called hyphae. These hyphae collectively form the mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus that lives beneath the surface. The mycelium acts as the primary water absorption system for the mushroom, efficiently drawing moisture from its environment. This process is essential because water is not only a solvent for nutrients but also a medium for transporting essential compounds within the fungal cells.

The efficiency of water absorption in mushrooms is largely due to the extensive surface area provided by the mycelium. Hyphae are incredibly thin and can branch out extensively, allowing them to explore a large volume of soil or substrate. This expansive network maximizes contact with water sources, even in environments with limited moisture. Additionally, the cell walls of hyphae are composed of chitin, a semi-permeable material that facilitates the passive uptake of water through osmosis. This mechanism ensures that water moves into the hyphae from the surrounding environment, driven by the concentration gradient of solutes.

Another key factor in water absorption is the presence of rhizomorphs, which are root-like structures formed by aggregated hyphae. Rhizomorphs are more robust than individual hyphae and can transport water over longer distances within the mycelium. They often grow toward areas with higher moisture content, acting as conduits to channel water to the growing mushroom. This targeted water transport ensures that the fruiting body (the visible mushroom) receives sufficient moisture to support its rapid growth and development.

The process of water absorption is also closely tied to nutrient uptake. As hyphae absorb water, they simultaneously take in dissolved minerals and organic compounds, which are essential for the mushroom's metabolic processes. This dual function of water absorption and nutrient acquisition highlights the efficiency of the mycelium as a nourishing structure. Without this efficient water absorption system, mushrooms would be unable to sustain their metabolic activities, including enzyme production, energy generation, and the synthesis of structural components.

In summary, the mycelium, with its hyphae and rhizomorphs, is the structure that allows growing mushrooms to efficiently draw moisture from their environment. This water absorption is vital for supporting metabolic processes, transporting nutrients, and maintaining the overall health of the fungus. By maximizing surface area and utilizing osmosis, mushrooms ensure a steady supply of water, even in challenging conditions, demonstrating the remarkable adaptability of these organisms.

Discovering Morel Mushrooms: Preferred Tree Species for Optimal Growth

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The mycelium, a network of thread-like filaments, allows the mushroom to absorb nutrients from its environment.

The mycelium secretes enzymes to break down organic matter in the substrate, converting it into nutrients the mushroom can absorb.

No, mushrooms do not have roots. Instead, they rely on the mycelium to extract nutrients from their surroundings.

No, the mycelium is essential for nutrient absorption; without it, the mushroom cannot sustain itself.