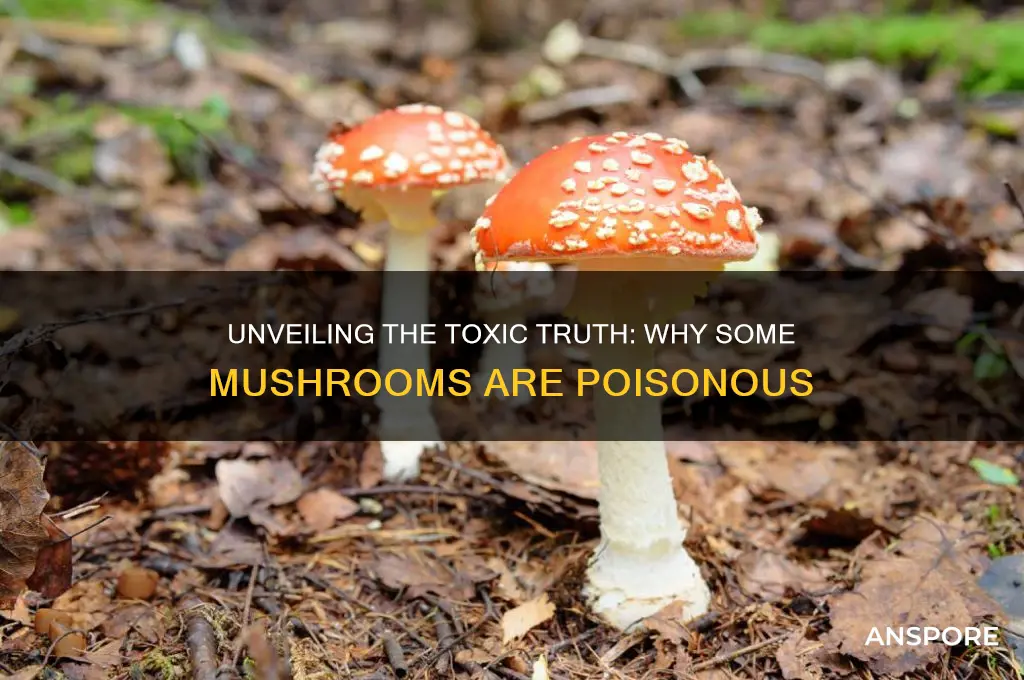

Mushrooms, while often celebrated for their culinary and medicinal properties, can also be highly toxic, posing significant risks to humans and animals. The toxicity of certain mushroom species arises from the presence of potent toxins, such as amatoxins, orellanine, and muscarine, which can cause severe symptoms ranging from gastrointestinal distress to organ failure and even death. Unlike plants, mushrooms lack the ability to produce seeds, relying instead on spores for reproduction, and their complex chemical compositions have evolved as defense mechanisms against predators. Identifying poisonous mushrooms can be challenging, as many toxic species closely resemble edible varieties, making knowledge of mycology and careful foraging practices essential to avoid accidental poisoning. Understanding why mushrooms are poisonous involves exploring their evolutionary biology, chemical defenses, and the ecological roles they play in their habitats.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Toxin Production | Many poisonous mushrooms produce toxins such as amatoxins (e.g., alpha-amanitin), orellanine, and muscarine, which can cause severe organ damage or failure. |

| Amatoxins | Found in species like Amanita phalloides (Death Cap) and Amanita bisporigera, these toxins inhibit RNA polymerase II, leading to liver and kidney failure. |

| Orellanine | Present in Cortinarius species, this toxin causes delayed kidney damage, often misdiagnosed due to symptom onset days after ingestion. |

| Muscarine | Found in Clitocybe and Inocybe species, it stimulates muscarinic acetylcholine receptors, causing sweating, salivation, and gastrointestinal distress. |

| Ibotenic Acid & Muscimol | Found in Amanita muscaria (Fly Agaric), these toxins act as neurotoxins, causing hallucinations, confusion, and loss of coordination. |

| Coprine | Present in Coprinus atramentarius, it causes an alcohol-like reaction when consumed with alcohol, leading to nausea, vomiting, and rapid heartbeat. |

| Gyromitrin | Found in Gyromitra species (False Morel), it converts to monomethylhydrazine, causing gastrointestinal and neurological symptoms. |

| Similarity to Edible Species | Many poisonous mushrooms resemble edible ones (e.g., Amanita phalloides vs. young Agaricus bisporus), leading to accidental ingestion. |

| Lack of Distinct Taste/Smell | Most poisonous mushrooms lack a distinct taste or smell, making them difficult to identify based on sensory cues alone. |

| Regional Variability | Toxicity can vary by region due to environmental factors, making it challenging to generalize mushroom safety. |

| Delayed Symptoms | Some toxins (e.g., orellanine, amatoxins) cause symptoms hours to days after ingestion, complicating diagnosis and treatment. |

| No Universal Antidote | There is no single antidote for all mushroom toxins, and treatment is often supportive or specific to the toxin involved. |

| Misidentification Risk | Amateur foragers often misidentify mushrooms, increasing the risk of poisoning. |

| Bioaccumulation | Some toxins can bioaccumulate in the body, leading to severe long-term effects with repeated exposure. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Toxins in Mushrooms: Certain species produce toxins harmful to humans, causing severe illness or death

- Misidentification Risks: Mistaking toxic mushrooms for edible ones is a common cause of poisoning

- Symptoms of Poisoning: Nausea, vomiting, hallucinations, organ failure, and neurological effects are typical symptoms

- Deadly Species: Amanita phalloides (Death Cap) and Galerina marginata are among the most lethal

- Prevention Tips: Avoid foraging without expertise, cook thoroughly, and consult guides or experts

Toxins in Mushrooms: Certain species produce toxins harmful to humans, causing severe illness or death

Mushrooms, often celebrated for their culinary and medicinal properties, harbor a darker side: certain species produce toxins that can be severely harmful or even fatal to humans. These toxins, evolved as defense mechanisms against predators, vary widely in their effects, from gastrointestinal distress to organ failure. Understanding which mushrooms contain these toxins and how they affect the body is crucial for anyone foraging or consuming wild fungi.

One of the most notorious toxins is amatoxin, found in the *Amanita* genus, including the infamous "Death Cap" (*Amanita phalloides*). Amatoxins cause severe liver and kidney damage, often with a delayed onset of symptoms (6–24 hours after ingestion). Initial signs like nausea and vomiting may seem benign, but they progress to jaundice, seizures, and coma within 2–3 days. Even a small bite—as little as 30 grams—can be lethal without immediate medical intervention, including liver transplantation in severe cases. Foragers must avoid mushrooms with white gills and a bulbous base, common traits of *Amanita* species.

Another toxin, muscarine, is associated with mushrooms like *Clitocybe* and *Inocybe*. Unlike amatoxins, muscarine acts quickly, within 15–30 minutes of ingestion, causing symptoms like excessive sweating, salivation, and blurred vision due to its stimulation of the parasympathetic nervous system. While rarely fatal, severe cases can lead to respiratory failure, particularly in children or the elderly. Dosage is critical here: as little as 10–20 milligrams of muscarine can trigger symptoms, but prompt administration of atropine, an antidote, can mitigate effects.

Orellanine, found in mushrooms like *Cortinarius rubellus*, targets the kidneys rather than the liver. Symptoms appear 2–3 days after ingestion and include thirst, frequent urination, and fatigue, progressing to kidney failure if untreated. Unlike amatoxin poisoning, orellanine toxicity is dose-dependent, with repeated consumption of small amounts posing a risk. There is no specific antidote, making avoidance the best strategy. Mushrooms with rusty-brown spores and a web-like cap veil should be avoided.

To stay safe, follow these practical tips: always consult a field guide or expert before consuming wild mushrooms, cook all mushrooms thoroughly (though this doesn’t neutralize all toxins), and never eat mushrooms raw unless their safety is confirmed. If poisoning is suspected, seek medical help immediately, bringing a sample of the mushroom for identification. While mushrooms offer incredible benefits, their toxins demand respect and caution.

Are Shiitake Mushrooms Poisonous? Debunking Myths and Facts

You may want to see also

Misidentification Risks: Mistaking toxic mushrooms for edible ones is a common cause of poisoning

Mushroom foraging, while rewarding, is fraught with peril due to the striking resemblance between toxic and edible species. The *Amanita phalloides*, or Death Cap, is a notorious example—its olive-green cap and white gills mimic the edible Paddy Straw mushroom (*Agaricus campestris*). A single Death Cap contains enough amatoxins to cause severe liver failure in an adult, with symptoms appearing 6–24 hours after ingestion, often too late for intervention. Misidentification here isn’t just a mistake; it’s potentially fatal.

Consider the *Galerina marginata*, a small brown mushroom often mistaken for edible *Cremini* or *Portobello* varieties. This "deadly doppelgänger" contains the same amatoxins as the Death Cap but in smaller doses, making it equally dangerous. Foragers often overlook its rusty-brown spores or slender stem, focusing instead on its size and color—a critical error. Even experienced hunters fall prey to this mimicry, underscoring the need for meticulous identification.

Children and pets are particularly vulnerable due to their curiosity and lower body mass. A child ingesting just a fragment of a toxic mushroom can suffer severe poisoning, as toxins like orellanine (found in *Cortinarius* species) accumulate rapidly in smaller bodies. Pets, attracted to mushrooms’ earthy scent, may consume them unnoticed, leading to kidney failure within days. Always inspect outdoor areas for mushrooms and teach children to "look but don’t touch."

To mitigate misidentification risks, follow these steps: 1) Use a reputable field guide or app (e.g., *Mushroom Expert*) to cross-reference findings. 2) Examine spore color by placing the cap on white paper overnight—a rusty hue signals *Galerina*. 3) Note habitat; toxic species like *Amanita* often grow near oaks, while edibles like *Chanterelles* prefer conifers. 4) When in doubt, consult a mycologist or local foraging group. Remember, no meal is worth risking your life.

The takeaway is clear: visual similarity is not a reliable indicator of edibility. Toxic mushrooms often lack immediate warning signs like foul odors or bright colors, making them deceptive. Relying on folklore (e.g., "animals avoid poisonous mushrooms") is dangerous, as wildlife tolerances differ from humans. Instead, adopt a "100% certainty or no consumption" rule. Misidentification risks are avoidable with knowledge, caution, and respect for nature’s complexity.

Spotting Deadly Fungi: A Guide to Identifying Poisonous Mushrooms Safely

You may want to see also

Symptoms of Poisoning: Nausea, vomiting, hallucinations, organ failure, and neurological effects are typical symptoms

Mushrooms, while often celebrated for their culinary and medicinal properties, can be a double-edged sword. Many species contain toxins that, when ingested, trigger a cascade of symptoms ranging from mild discomfort to life-threatening conditions. Understanding these symptoms is crucial for anyone who forages or consumes wild mushrooms, as early recognition can mean the difference between a quick recovery and severe health consequences.

Children and pets are particularly vulnerable due to their smaller body mass and tendency to ingest unfamiliar objects. For example, a child consuming a single *Galerina marginata* (Deadly Galerina) cap could experience symptoms within 6–12 hours, starting with nausea and progressing to seizures or coma. Pet owners should note that dogs are attracted to the meaty scent of mushrooms like *Clitocybe dealbata* (Ivory Funnel), which causes severe gastrointestinal upset and, in some cases, muscle tremors within 1–3 hours of ingestion.

If poisoning is suspected, immediate action is essential. Inducing vomiting can help if the ingestion occurred within the last hour, but this should not replace professional medical care. Activated charcoal, administered by a healthcare provider, can bind toxins in the digestive tract. For amatoxin poisoning, hospitalization is mandatory, as patients often require liver transplants in severe cases. Psilocybin-related incidents typically resolve within 6–8 hours but may necessitate sedation if panic or agitation occurs.

Prevention remains the best strategy. Always consult a mycologist or use a reputable field guide when foraging. Avoid consuming any mushroom unless its identity is confirmed with 100% certainty. Cooking does not neutralize most mushroom toxins, so visual identification alone is insufficient. For those who enjoy mushroom hunting, investing in a spore print kit or DNA testing can provide additional assurance. Remember, the adage "there are old mushroom hunters and bold mushroom hunters, but no old, bold mushroom hunters" holds true—caution saves lives.

Wild Mushrooms and Dogs: Poisonous Risks and Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$15.8 $17.99

Deadly Species: Amanita phalloides (Death Cap) and Galerina marginata are among the most lethal

Mushrooms, often celebrated for their culinary and medicinal benefits, harbor a darker side. Among the thousands of species, a select few are deadly, with Amanita phalloides (Death Cap) and Galerina marginata standing out as two of the most lethal. These fungi are not just poisonous; they are insidious, often resembling edible varieties and causing symptoms that delay treatment, increasing their fatality rate. Understanding their toxicity is crucial for anyone foraging or even gardening, as both species thrive in temperate regions and can appear in unexpected places, such as urban parks or backyards.

The toxicity of Amanita phalloides lies in its potent hepatotoxins, primarily alpha-amanitin. This toxin inhibits RNA polymerase II, a critical enzyme for protein synthesis, leading to liver failure. Symptoms are deceptively delayed, appearing 6–24 hours after ingestion, starting with gastrointestinal distress (vomiting, diarrhea) and progressing to jaundice, seizures, and coma within 3–6 days. A single Death Cap contains enough toxin to kill an adult, and even small amounts can be fatal, especially in children. Treatment requires immediate medical intervention, including activated charcoal, intravenous fluids, and, in severe cases, liver transplantation. Foragers must note its distinctive features: a greenish-yellow cap, white gills, and a volva (cup-like base), though these can be obscured by soil or decay.

Galerina marginata, often mistaken for edible brown mushrooms like *Psathyrella* or *Pholiota*, contains the same amatoxins as the Death Cap. Its toxicity is equally lethal, with symptoms mirroring those of *Amanita phalloides*. What makes *Galerina* particularly dangerous is its unassuming appearance—small, brown, and nondescript—and its habit of growing on wood, often in clusters. Even experienced foragers have fallen victim to its resemblance to edible wood-dwelling species. A fatal dose is as little as 10–20 grams, and misidentification is common due to its lack of striking features. Unlike the Death Cap, *Galerina* lacks a volva, but its attached gills and rusty-brown spores are key identifiers.

Comparing these two species highlights a critical lesson: toxicity is not always advertised. While some poisonous mushrooms have bright colors or distinctive odors, *Amanita phalloides* and *Galerina marginata* blend into their environments, their lethality hidden beneath innocuous exteriors. This underscores the importance of expert identification and the adage, "When in doubt, throw it out." Foraging without proper knowledge is akin to playing Russian roulette, with these species being two of the most dangerous chambers.

To protect yourself, follow these practical steps: avoid picking mushrooms unless you are 100% certain of their identity, consult a mycologist or field guide with spore prints, and never consume wild mushrooms raw. Educate children about the dangers of ingesting unknown fungi, especially in areas where these species are prevalent. If poisoning is suspected, seek emergency medical care immediately, bringing a sample of the mushroom for identification. Awareness and caution are the best defenses against these silent killers, ensuring that the beauty of mushrooms is admired, not feared.

Are Big White Mushrooms Poisonous? A Guide to Safe Identification

You may want to see also

Prevention Tips: Avoid foraging without expertise, cook thoroughly, and consult guides or experts

Mushrooms, with their diverse shapes and colors, often lure foragers into a false sense of familiarity. Yet, the forest floor is a minefield of look-alikes, where a single misidentified species can lead to severe poisoning or even death. Avoid foraging without expertise—this is the cardinal rule. Novice foragers frequently mistake deadly species like the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) for edible varieties such as the Paddy Straw mushroom (*Agaricus campestris*). The consequences of such errors are dire: gastrointestinal distress, organ failure, or fatalities within days. Investing in formal mycology training or apprenticing under an experienced forager can save lives. Until then, stick to store-bought mushrooms, where safety is guaranteed.

Cooking mushrooms thoroughly is another critical step often overlooked. While some toxins, like those in the Amanita genus, are heat-stable and require specific preparation methods, many harmful compounds break down with heat. For instance, raw mushrooms of the *Coprinus* genus contain coprine, which can cause discomfort when consumed with alcohol. Boiling or sautéing these mushrooms for at least 10 minutes neutralizes the toxin, making them safe to eat. Always err on the side of caution: cook wild mushrooms until they are visibly softened and any liquid released has evaporated. This simple practice can mitigate risks associated with mild toxins or improperly identified species.

Consulting guides or experts is not just a suggestion—it’s a necessity. Field guides, while helpful, can be misleading without proper training. For example, the Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*) closely resembles the edible Meadow Mushroom (*Agaricus campestris*), but the former is lethally toxic. Apps and online forums are no substitute for hands-on expertise. Instead, join local mycological societies or attend foraging workshops led by certified experts. These resources provide real-time identification assistance and teach nuanced characteristics, such as spore color or gill attachment, that field guides often gloss over.

Combining these prevention tips creates a robust safety net. Foraging without expertise is akin to playing Russian roulette with nature’s bounty. Cooking thoroughly addresses many, though not all, toxin concerns. Consulting guides or experts bridges the knowledge gap, turning a risky endeavor into an educational and rewarding experience. Together, these practices ensure that the allure of wild mushrooms doesn’t overshadow their potential dangers. Remember: when in doubt, throw it out—or better yet, leave it in the ground.

Are Mowers Mushrooms Poisonous to Dogs? Risks and Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Some mushrooms are poisonous because they contain toxins produced by certain fungi as a defense mechanism against predators or to gain a competitive advantage in their environment.

Poisonous mushrooms can cause a range of symptoms, from mild gastrointestinal issues like nausea and vomiting to severe reactions such as organ failure, depending on the type of toxin present.

No, it’s not always possible to identify a poisonous mushroom by its appearance alone. Some toxic mushrooms resemble edible ones, making proper identification by an expert essential.

No, not all wild mushrooms are poisonous. Many are edible and safe to consume, but it’s crucial to accurately identify them, as misidentification can be dangerous.

Poisonous mushrooms exist in nature as part of the fungi’s evolutionary strategy to deter animals and humans from consuming them, ensuring their survival and reproduction.