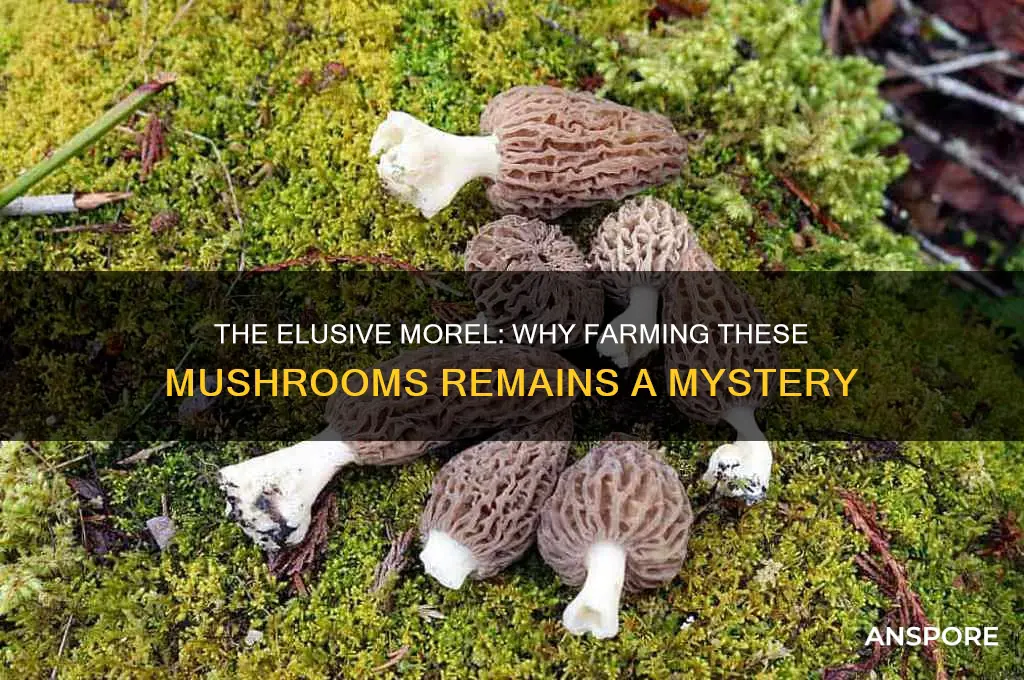

Morel mushrooms are highly prized for their unique flavor and texture, but cultivating them on a large scale remains a significant challenge for farmers. Unlike common button mushrooms, which thrive in controlled environments, morels are notoriously difficult to farm due to their complex and poorly understood life cycle. These fungi have a symbiotic relationship with specific trees and require precise environmental conditions, such as particular soil types, moisture levels, and temperature fluctuations, to grow. Additionally, morels are known to fruit unpredictably, often appearing in the wild after forest fires or other disturbances. Despite decades of research, scientists have yet to fully replicate these conditions in a controlled setting, making morel farming economically unfeasible for most growers. As a result, the majority of morels available in markets are foraged from the wild, contributing to their rarity and high cost.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Mycorrhizal Relationship | Morels form a symbiotic relationship with specific tree species (e.g., elm, ash, cottonwood), requiring their roots for nutrient exchange. This dependency makes controlled cultivation challenging. |

| Environmental Sensitivity | Morels require precise conditions: specific soil pH (6.0–7.0), moisture levels, temperature (50–70°F), and humidity. Slight deviations can prevent fruiting. |

| Sporulation Difficulty | Morel spores are slow to germinate and require specific triggers (e.g., fire, soil disturbance) to initiate growth, which are hard to replicate artificially. |

| Lack of Full Life Cycle Understanding | The complete life cycle of morels, including their saprotrophic and mycorrhizal phases, is not fully understood, hindering consistent cultivation. |

| Contamination Risk | Morel mycelium is susceptible to contamination by molds, bacteria, and competing fungi, reducing success rates in controlled environments. |

| Seasonal Variability | Morels fruit unpredictably based on seasonal weather patterns (e.g., spring rains, temperature fluctuations), making year-round cultivation difficult. |

| Genetic Diversity | Morels exhibit high genetic variability, with different strains requiring unique conditions, complicating standardized farming methods. |

| Commercial Viability | Despite some successes in small-scale cultivation, the cost and complexity of replicating natural conditions limit large-scale commercial production. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Lack of Mycorrhizal Relationship: Morels require specific tree partnerships, not replicable in controlled farming

- Spores vs. Fruiting: Spores grow mycelium, but fruiting bodies (mushrooms) are unpredictable and rare

- Environmental Sensitivity: Morels need precise soil, moisture, and temperature conditions, hard to maintain

- Seasonal Dependency: They only fruit in spring, limiting cultivation to a short window

- Commercial Viability: High demand but low supply due to inability to farm consistently or at scale

Lack of Mycorrhizal Relationship: Morels require specific tree partnerships, not replicable in controlled farming

Morels, those elusive and prized fungi, have long resisted domestication due to their intricate relationship with specific tree species. Unlike button mushrooms, which thrive in controlled environments, morels depend on a mycorrhizal partnership—a symbiotic bond where fungal networks exchange nutrients with tree roots. This relationship is so finely tuned that replicating it artificially remains beyond our current capabilities. Without the right tree host, morels simply won’t grow, making large-scale farming a biological puzzle yet to be solved.

Consider the process of establishing this partnership in nature. Morel mycelium intertwines with the roots of trees like ash, oak, or poplar, creating a network that benefits both parties. The tree provides carbohydrates, while the fungus delivers essential minerals and water. Recreating this in a controlled setting requires not only the right tree species but also the precise soil conditions, pH levels, and microbial communities that support this exchange. Even small deviations—such as incorrect soil moisture or incompatible tree varieties—can disrupt the partnership, halting morel growth.

Attempts to farm morels often overlook the complexity of this relationship, focusing instead on environmental factors like temperature and humidity. While these are important, they are secondary to the mycorrhizal bond. For instance, some growers have tried inoculating soil with morel mycelium near compatible trees, only to find inconsistent results. The issue lies in the unpredictability of the partnership: even if the mycelium colonizes the roots, the trees may not provide the necessary nutrients in the required quantities, or the timing of nutrient exchange may be off. This unpredictability underscores the challenge of replicating a process that evolved over millennia.

Practical tips for those attempting to cultivate morels include selecting the right tree species and ensuring the soil is rich in organic matter. For example, planting young poplar or ash trees in a well-drained, loamy soil with a pH between 6.0 and 7.0 can create a favorable environment. However, even with these steps, success is not guaranteed. Monitoring the health of both the trees and the mycelium is crucial, as is patience—morels may take years to establish a productive relationship with their hosts.

In conclusion, the lack of a replicable mycorrhizal relationship remains the primary barrier to farming morels. While advancements in mycology may one day unlock this mystery, for now, morels remain a wild harvest, their growth tied to the intricate dance between fungus and tree. Until we can fully mimic this partnership, morel farming will remain more art than science, a testament to the limits of human intervention in nature’s processes.

Where to Buy Shrooms: A Guide to Finding Quality Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Spores vs. Fruiting: Spores grow mycelium, but fruiting bodies (mushrooms) are unpredictable and rare

Morel mushrooms, prized for their earthy flavor and elusive nature, remain a forager’s dream rather than a farmer’s crop due to the stark contrast between spore behavior and fruiting body production. Spores, the microscopic reproductive units of fungi, readily grow into mycelium—the vegetative network that forms the mushroom’s underground infrastructure. This mycelium can thrive in controlled environments, spreading through soil or substrate with relative predictability. However, the transition from mycelium to fruiting bodies (the mushrooms themselves) is where the challenge lies. While spores guarantee mycelial growth, they offer no assurance of fruiting, which is influenced by a complex interplay of environmental factors that remain difficult to replicate artificially.

Consider the process as a two-step puzzle: the first step, growing mycelium from spores, is straightforward and reliable. Spores, when introduced to a suitable medium, germinate and develop into mycelium with minimal intervention. This stage is akin to planting seeds that sprout without fail. The second step, however, is where the unpredictability emerges. Fruiting requires specific triggers—such as temperature fluctuations, humidity levels, and soil composition—that mimic the mushroom’s natural habitat. Unlike mycelium, which grows consistently, fruiting bodies are rare and sporadic, even in ideal conditions. This disparity explains why morel spores can colonize a substrate but rarely produce the coveted mushrooms in a controlled setting.

To illustrate, imagine cultivating morels in a greenhouse. Spores are sown, and mycelium spreads through the soil, seemingly thriving. Yet, despite optimal conditions, fruiting bodies may never appear. This phenomenon is not due to a lack of effort but to the mushroom’s inherent biology. Morels are believed to form symbiotic relationships with specific trees or require soil disturbances like wildfires, conditions impossible to replicate on a commercial scale. Even successful attempts at fruiting often yield inconsistent results, with harvests varying wildly from year to year. This unpredictability makes morel farming economically unviable compared to other crops.

For the aspiring cultivator, understanding this distinction is crucial. While spores are a reliable starting point, they are not a guarantee of mushrooms. Efforts to farm morels often focus on manipulating environmental factors to induce fruiting, but these attempts remain experimental. Practical tips include using spore slurries to inoculate outdoor beds near deciduous trees, maintaining soil pH between 6.0 and 7.0, and ensuring temperatures fluctuate between 50°F and 70°F. However, even with these measures, success is not assured. The takeaway is clear: spores grow mycelium, but fruiting bodies remain a rare and unpredictable reward, keeping morels firmly in the realm of foraging rather than farming.

Can You Eat Paddy Straw Mushrooms Raw? Safety Tips Revealed

You may want to see also

Environmental Sensitivity: Morels need precise soil, moisture, and temperature conditions, hard to maintain

Morels thrive in a delicate ecological niche, demanding a trifecta of specific soil composition, moisture levels, and temperature ranges. Their mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus, requires a pH between 6.0 and 7.5, slightly acidic to neutral. This narrow range excludes most agricultural soils, which are often amended for crops with broader pH tolerances. Additionally, morels favor soil rich in organic matter, particularly from decaying hardwood trees like elm, ash, and oak. Replicating this natural substrate artificially is challenging, as it involves not just the right materials but also the precise decomposition stage of those materials.

Consider moisture, another critical factor. Morels need a Goldilocks zone of soil moisture—not too dry, not too wet, but just right. This balance is notoriously difficult to maintain, especially in controlled environments. Too much water can lead to rot, while too little stunts growth. In nature, morels often appear after spring rains, but this timing is influenced by a complex interplay of soil absorption rates, evaporation, and microbial activity. Mimicking these conditions requires sophisticated irrigation systems and constant monitoring, making it impractical for large-scale farming.

Temperature plays an equally pivotal role in morel cultivation. The fungus requires a cool period, typically below 50°F (10°C), followed by a warmer phase around 60–70°F (15–21°C) to fruit. This temperature shift mimics the natural transition from winter to spring. Achieving this in a controlled setting demands precise climate control, which is energy-intensive and costly. Even with advanced technology, maintaining these conditions consistently across a growing season is fraught with challenges, from equipment malfunctions to external weather fluctuations.

Attempts to farm morels often overlook the symbiotic relationships they form with trees and soil microorganisms. In the wild, morels engage in mycorrhizal associations with tree roots, exchanging nutrients in a mutually beneficial partnership. Recreating this dynamic artificially is nearly impossible, as it involves not just the right species but also the correct developmental stages of both fungus and tree. Without this symbiosis, morels struggle to absorb essential nutrients, leading to poor yields or failure.

For those determined to experiment with morel cultivation, start small and focus on mimicking natural conditions. Use a mix of well-decomposed hardwood chips and soil with a pH of 6.5, keep moisture levels consistent at 50–60% field capacity, and maintain temperatures within the specified ranges. However, even with meticulous care, success is not guaranteed. The environmental sensitivity of morels underscores why they remain a forager’s treasure rather than a farmer’s crop.

Mind-Altering Mushrooms: Can Fungi Influence Human Behavior and Control?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Seasonal Dependency: They only fruit in spring, limiting cultivation to a short window

Morel mushrooms, prized for their earthy flavor and elusive nature, are bound to spring’s fleeting embrace. Unlike cultivated crops that can be coaxed into year-round production, morels stubbornly adhere to a narrow fruiting window, typically lasting just 4–6 weeks between April and June in the Northern Hemisphere. This seasonal dependency isn’t merely a quirk—it’s a biological imperative tied to their symbiotic relationship with trees, soil temperature, and moisture levels. For farmers, this means no amount of greenhouse manipulation or artificial lighting can extend their harvest season, making large-scale cultivation a logistical and economic challenge.

Consider the steps required to mimic morels’ natural environment. First, you’d need to replicate the precise soil conditions of a deciduous forest floor, rich in decaying hardwood and with a pH between 6.0 and 7.5. Next, you’d have to maintain a consistent temperature range of 50–60°F (10–15°C), which is only naturally achievable during spring. Even then, humidity levels must hover around 80–90%, and the soil must retain moisture without becoming waterlogged. These conditions are not only difficult to control but also unsustainable for year-round farming. For instance, heating and humidifying a large enough space to support commercial morel production would be prohibitively expensive, with energy costs dwarfing potential profits.

The comparative rarity of morels further underscores the challenge. While shiitake or button mushrooms can be grown in controlled environments with predictable yields, morels remain a wild harvest, their fruiting bodies appearing only after specific environmental cues. This unpredictability makes it nearly impossible to guarantee a consistent supply, a critical factor for restaurants and markets. Even successful small-scale morel cultivation experiments, like those using wood chips inoculated with morel spawn, still rely on spring’s natural rhythms and produce yields far below what’s needed for commercial viability.

From a persuasive standpoint, embracing morels’ seasonal nature could be reframed as an opportunity rather than a limitation. Their springtime exclusivity adds to their allure, driving demand and commanding premium prices. Instead of fighting their natural cycle, farmers and foragers could lean into it, creating seasonal markets or pop-up events that celebrate morels’ fleeting presence. For home growers, this means planning ahead: inoculate your outdoor beds with morel spawn in fall, ensure the soil is rich in organic matter, and wait patiently for spring’s arrival. While you can’t control the season, you can position yourself to reap its rewards.

In conclusion, morels’ seasonal dependency isn’t just a hurdle—it’s a defining characteristic that shapes their value and cultivation potential. For now, their springtime fruiting remains a natural mystery, one that resists human intervention. Whether you’re a farmer, chef, or enthusiast, understanding and respecting this cycle is key to appreciating morels in their truest form. After all, their rarity is part of what makes them so extraordinary.

Boosting Feline Health: Mushrooms' Role in Strengthening Cats' Immune Systems

You may want to see also

Commercial Viability: High demand but low supply due to inability to farm consistently or at scale

Morel mushrooms, prized for their earthy flavor and meaty texture, command premium prices in gourmet markets, yet their commercial cultivation remains elusive. Unlike button mushrooms, which thrive in controlled environments, morels stubbornly resist domestication. Their mycelium—the vegetative part of the fungus—grows unpredictably, and the conditions required for fruiting are complex and poorly understood. This inconsistency makes large-scale farming a gamble, with no guaranteed yield despite significant investment. As a result, the market relies heavily on foraged morels, which are seasonal and geographically limited, driving up prices and creating a persistent gap between supply and demand.

To understand the challenge, consider the steps required to cultivate morels. First, growers must mimic the mushroom’s natural habitat, which often involves specific soil types, moisture levels, and symbiotic relationships with trees. Even with these conditions in place, success is not assured. For instance, attempts to use sterile substrates or controlled environments have yielded mixed results, with some trials producing no fruiting bodies at all. The lack of standardized methods means that each cultivation effort is essentially an experiment, making it difficult to scale operations or predict costs. This unpredictability deters commercial growers, who prioritize reliability and efficiency.

From a market perspective, the scarcity of morels only heightens their appeal. Chefs and consumers are willing to pay upwards of $50 per pound for fresh morels, and dried varieties can fetch even higher prices. However, this demand cannot be met through foraging alone, which is labor-intensive and subject to environmental fluctuations. Efforts to bridge the supply gap through cultivation have been stymied by the mushroom’s recalcitrance, leaving the industry in a state of limbo. Until reliable farming techniques are developed, morels will remain a luxury item, accessible only to those willing to pay a premium.

A comparative analysis of morel cultivation versus other specialty crops reveals the depth of the problem. Truffles, another high-value fungus, have seen limited success in cultivation through truffle orchards, but this process takes years to establish and requires specific tree species. In contrast, morels lack even this partial solution. While crops like saffron or vanilla also face cultivation challenges, they can be grown consistently, albeit with high labor costs. Morels, however, remain a wild card, with no clear path to domestication. This uniqueness underscores their allure but also their commercial limitations.

For aspiring growers, the takeaway is clear: cultivating morels is not for the faint of heart. While small-scale experiments may yield modest results, large-scale production remains a pipe dream. Instead, focusing on sustainable foraging practices or investing in research to unlock the secrets of morel mycelium may offer more viable paths forward. Until then, the high demand for morels will continue to outstrip supply, ensuring their status as a coveted but elusive delicacy.

When to Harvest Mushrooms: Timing Tips for Optimal Growth and Flavor

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Morel mushrooms cannot be easily farmed because they have a complex symbiotic relationship with specific trees and soil conditions, and their exact growth requirements are not fully understood.

A: While some attempts have been made, morel mushrooms are notoriously difficult to cultivate indoors due to their need for specific soil microbes, tree roots, and environmental conditions that are hard to replicate artificially.

A: Morel mushrooms require a unique combination of factors, including decaying wood, specific soil pH, and a symbiotic relationship with certain tree species, which are not present in standard mushroom farming environments.

A: While it is extremely challenging, some small-scale operations have had limited success in cultivating morels. However, it remains largely unfeasible for commercial farming due to the high costs and unpredictable yields.