Fungi grow mushrooms as a reproductive strategy to disperse their spores and ensure the continuation of their species. Unlike plants, fungi lack the ability to produce seeds, so they rely on mushrooms—the fruiting bodies of certain fungi—to release spores into the environment. These spores are lightweight and can travel through air or water to colonize new habitats. Mushrooms typically emerge when conditions are favorable, such as in damp, nutrient-rich environments, and their growth is triggered by factors like temperature, humidity, and available organic matter. By producing mushrooms, fungi maximize their chances of spreading genetically diverse offspring, allowing them to thrive in diverse ecosystems and play crucial roles in nutrient cycling and decomposition.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproductive Structures | Mushrooms are the fruiting bodies of fungi, produced to facilitate reproduction. |

| Spore Dispersal | Mushrooms release spores into the environment, aiding in the spread and colonization of new habitats. |

| Resource Allocation | Fungi allocate energy and nutrients to grow mushrooms when conditions (moisture, temperature, nutrients) are optimal. |

| Survival Strategy | Mushrooms help fungi survive by dispersing spores over long distances, ensuring species continuity. |

| Ecosystem Role | Mushrooms contribute to nutrient cycling by breaking down organic matter and releasing nutrients back into the ecosystem. |

| Symbiotic Relationships | Some fungi grow mushrooms as part of symbiotic relationships (e.g., mycorrhizae) to support plant growth. |

| Environmental Cues | Mushroom growth is triggered by specific environmental cues, such as changes in light, humidity, or substrate availability. |

| Genetic Programming | Fungi are genetically programmed to produce mushrooms as part of their life cycle for reproductive success. |

| Adaptability | Mushrooms allow fungi to adapt to diverse environments by dispersing spores in various ways (wind, water, animals). |

| Decomposition | Mushrooms aid in decomposing complex organic materials, recycling nutrients in ecosystems. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Nutrient dispersal mechanisms

Fungi grow mushrooms primarily as a reproductive strategy, but this process is intimately tied to their nutrient dispersal mechanisms. Mushrooms are the fruiting bodies of fungi, and their primary function is to produce and disperse spores, which are akin to fungal seeds. However, the growth of mushrooms also serves as a critical mechanism for nutrient dispersal and acquisition. Fungi are heterotrophic organisms, meaning they cannot produce their own food and must obtain nutrients from their environment. Mushrooms facilitate this by extending the reach of the fungal network, known as the mycelium, into new areas where nutrients can be absorbed and distributed.

One key nutrient dispersal mechanism involves the physical structure of the mushroom itself. As mushrooms grow above ground, they expose the fungal network to a broader environment, increasing the surface area available for nutrient absorption. The mycelium, which remains hidden beneath the surface, secretes enzymes that break down complex organic matter—such as dead plants, wood, or other organic debris—into simpler compounds that the fungus can absorb. The mushroom acts as a conduit, channeling these nutrients back into the mycelial network, where they are distributed throughout the fungal colony. This process ensures that nutrients are efficiently recycled and utilized by the fungus.

Another important mechanism is the role of mushrooms in symbiotic relationships, particularly mycorrhizal associations with plants. In these relationships, fungi form mutualistic partnerships with plant roots, where the fungus provides essential nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus to the plant in exchange for carbohydrates produced by photosynthesis. Mushrooms enhance this nutrient exchange by extending the mycelial network into the soil, increasing the fungus's ability to access and mobilize nutrients. The spores and debris from decaying mushrooms also contribute organic matter to the soil, enriching it and creating a more fertile environment for both the fungus and its plant partners.

Mushrooms further aid in nutrient dispersal through their spore dispersal mechanisms. As spores are released into the environment, they can land on new substrates rich in organic matter, allowing the fungus to colonize additional nutrient sources. This colonization expands the fungal network, enabling the fungus to tap into previously inaccessible resources. Additionally, the act of spore dispersal often involves the breakdown and redistribution of organic materials, as spores carry with them enzymes and other compounds that facilitate nutrient cycling. This process not only benefits the fungus but also contributes to ecosystem health by decomposing organic matter and releasing nutrients back into the environment.

Finally, the growth of mushrooms supports nutrient dispersal by promoting ecological interactions. Mushrooms serve as food sources for various organisms, including insects, mammals, and microorganisms. As these organisms consume mushrooms, they inadvertently transport fungal spores and mycelial fragments to new locations, further extending the fungus's reach. The decomposition of mushrooms by detritivores also releases nutrients into the soil, creating a feedback loop that enhances nutrient availability for the fungal network and surrounding biota. Thus, mushrooms are not just reproductive structures but integral components of fungal nutrient dispersal and ecosystem nutrient cycling.

Are Magic Mushroom Grow Kits Legal in Ireland? What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

Spores and reproduction strategies

Fungi grow mushrooms primarily as a reproductive strategy to disperse spores, the microscopic units of fungal reproduction. Unlike plants, fungi do not rely on seeds or flowers for reproduction. Instead, mushrooms serve as spore-producing structures, typically bearing gills, pores, or teeth where spores are generated in vast quantities. These spores are analogous to plant seeds but are far smaller and more numerous, allowing fungi to colonize new environments efficiently. The mushroom’s primary function is to elevate the spore-bearing structures above the substrate, increasing the chances of spore dispersal via air, water, or animals.

Spores are produced through both sexual and asexual reproduction, depending on the fungal species and environmental conditions. In sexual reproduction, spores (often called meiospores) are formed through the fusion of haploid cells, resulting in genetic diversity. This diversity is crucial for fungi to adapt to changing environments and resist pathogens. Asexual spores, such as conidia, are produced by mitosis and are genetically identical to the parent fungus, allowing for rapid colonization of favorable habitats. Mushrooms are typically involved in sexual spore production, as they provide a structured environment for the complex processes of mating and spore development.

The dispersal of spores is a critical aspect of fungal reproduction, and mushrooms have evolved various strategies to maximize their spread. Some mushrooms release spores passively, relying on air currents to carry them away. Others use active mechanisms, such as the forcible ejection of spores seen in certain species like puffballs. Additionally, mushrooms often have hygroscopic structures (e.g., gills that respond to moisture changes) that aid in spore release. Once dispersed, spores can remain dormant for extended periods, waiting for optimal conditions to germinate and grow into new fungal colonies.

Mushrooms also play a role in attracting spore dispersers, particularly insects and other small animals. Bright colors, distinct shapes, and sometimes even odors can lure creatures that inadvertently carry spores on their bodies to new locations. This mutualistic relationship benefits both the fungus, which gains wider dispersal, and the animals, which may feed on the mushroom tissue. Such strategies highlight the adaptability and sophistication of fungal reproductive mechanisms.

In summary, mushrooms are the reproductive organs of fungi, designed to produce and disperse spores efficiently. Through sexual and asexual reproduction, fungi ensure genetic diversity and rapid colonization. The structure and positioning of mushrooms optimize spore dispersal, whether through passive or active means, and their interactions with other organisms further enhance their reproductive success. Understanding these strategies sheds light on why fungi invest energy in growing mushrooms and how they thrive in diverse ecosystems.

Mastering Reishi Mushroom Cultivation: A Step-by-Step Growing Guide

You may want to see also

Environmental triggers for fruiting

Fungi produce mushrooms as part of their reproductive cycle, and this process, known as fruiting, is triggered by specific environmental conditions. These triggers are essential for the fungus to allocate energy toward producing fruiting bodies, which release spores to propagate the species. One of the primary environmental cues for fruiting is changes in temperature. Many fungi are sensitive to temperature fluctuations, particularly a drop in temperature, which signals the transition from vegetative growth to reproductive growth. For example, some species of mushrooms, like those in the genus *Coprinus*, are known to fruit after a period of cooler weather, often in autumn when temperatures begin to decline. This temperature shift mimics the natural seasonal changes that fungi have evolved to respond to.

Moisture is another critical environmental trigger for mushroom fruiting. Fungi require adequate water to initiate and sustain the development of fruiting bodies. Rainfall or increased humidity can stimulate fruiting, as water is essential for spore dispersal and the structural integrity of the mushroom. However, the timing and amount of moisture are crucial; too much water can lead to rot, while too little can inhibit fruiting altogether. Many fungi have adapted to fruit shortly after rain events, taking advantage of the moisture to rapidly develop mushrooms and release spores before conditions dry out again.

Light exposure also plays a role in triggering fruiting, though its effects are more subtle and species-specific. Some fungi require light to initiate fruiting, as light can signal the presence of an open environment suitable for spore dispersal. For instance, species like *Psathyrella* often fruit in response to low-light conditions, while others, such as *Stropharia*, may require more direct light. The quality and duration of light can influence the timing and success of fruiting, with some fungi responding to specific wavelengths or photoperiods.

Nutrient availability is another key factor that can trigger fruiting in fungi. When a fungus has exhausted readily available nutrients in its substrate, it may allocate energy toward reproduction as a survival strategy. This is often observed in wood-decaying fungi, which fruit after breaking down lignin and cellulose in dead wood. Additionally, changes in the chemical composition of the substrate, such as a decrease in nitrogen levels, can signal the fungus to transition to fruiting. This ensures that the fungus maximizes its chances of spreading spores before resources are completely depleted.

Finally, physical disturbances in the environment can act as triggers for fruiting. Activities like tilling soil, digging, or even animal activity can expose fungal mycelium to air and light, prompting the formation of mushrooms. This is particularly common in species that grow in symbiotic relationships with plants or in disturbed habitats. For example, *Amanita* species often fruit after the soil has been disturbed, as this creates an opportunity for spore dispersal in open areas. These disturbances mimic natural events like burrowing animals or falling trees, which fungi have evolved to respond to as cues for reproduction.

Understanding these environmental triggers is crucial for both naturalists and cultivators, as it allows for the prediction and manipulation of fruiting events. By controlling factors like temperature, moisture, light, nutrient availability, and physical disturbances, it is possible to encourage fungi to produce mushrooms in desired conditions, whether in the wild or in controlled environments like mushroom farms.

Melbourne's Mushroom Growing Guide: Optimal Timing for Bountiful Harvests

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$18.49 $29.99

Role in ecosystem decomposition

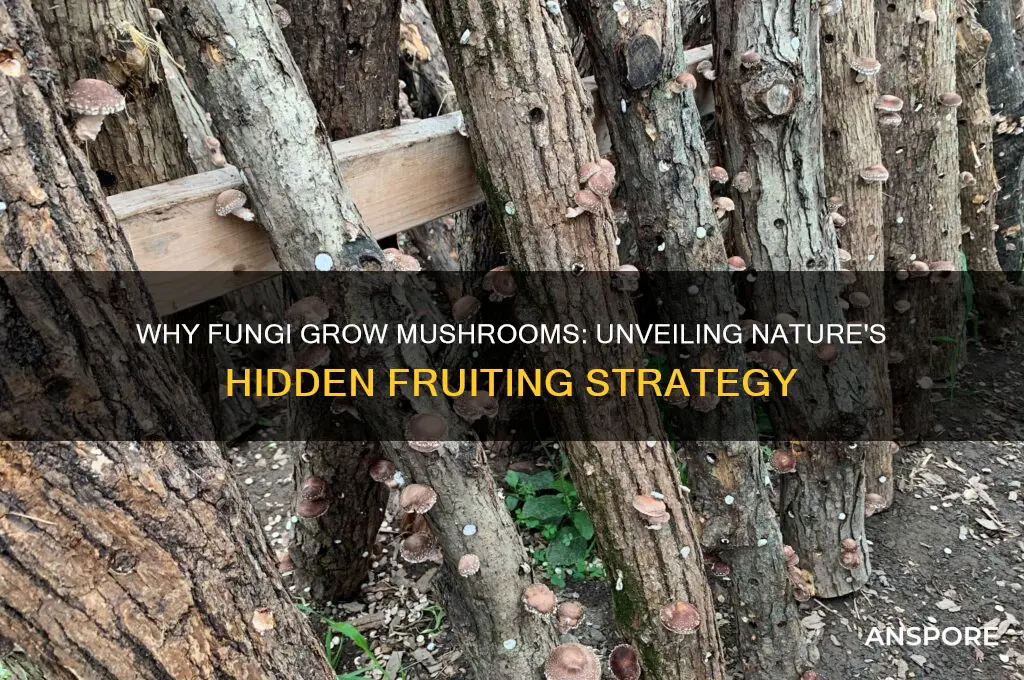

Fungi play a pivotal role in ecosystem decomposition, acting as primary decomposers that break down complex organic matter into simpler substances. Unlike plants, fungi lack chlorophyll and cannot photosynthesize, so they rely on absorbing nutrients from dead or decaying material. Mushrooms, the visible fruiting bodies of certain fungi, are essential in this process as they facilitate the dispersal of spores, ensuring the continuation of fungal colonies. When fungi grow mushrooms, they are essentially signaling their presence and expanding their reach to decompose more organic matter. This decomposition process is critical for nutrient cycling, as fungi break down lignin and cellulose—complex compounds found in plant material—that many other organisms cannot digest.

In ecosystems, fungi decompose a wide range of organic materials, including fallen leaves, dead trees, and even animal remains. By secreting enzymes that break down these materials, fungi release nutrients like carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus back into the soil. This nutrient recycling is vital for plant growth and overall ecosystem health. Mushrooms, as part of the fungal life cycle, contribute to this process by producing spores that can colonize new substrates, ensuring continuous decomposition. Without fungi, organic matter would accumulate, and essential nutrients would remain locked away, hindering ecosystem productivity.

The role of fungi in decomposition is particularly significant in forests, where they act as the primary decomposers of wood. Wood is rich in lignin, a tough polymer that most organisms cannot break down. Fungi, however, possess enzymes capable of degrading lignin, allowing them to access the cellulose and other nutrients within. Mushrooms growing on decaying logs or trees are a visible sign of this process, indicating that fungi are actively breaking down the wood and returning nutrients to the soil. This activity supports the growth of new plants and maintains the forest's nutrient balance.

Fungi also collaborate with other organisms in decomposition processes, forming symbiotic relationships that enhance their efficiency. For example, mycorrhizal fungi form partnerships with plant roots, helping plants absorb water and nutrients while receiving carbohydrates in return. This mutualism accelerates decomposition and nutrient cycling, benefiting both the fungi and their plant hosts. Mushrooms, as reproductive structures, ensure the survival and spread of these fungal networks, reinforcing their role in ecosystem decomposition.

In addition to their direct decomposing activity, fungi contribute to soil structure and health. As they grow through organic matter, their hyphae (thread-like structures) bind soil particles together, improving aeration and water retention. This enhances the soil's ability to support plant life and microbial activity. Mushrooms, by dispersing fungal spores, help maintain these beneficial soil conditions across larger areas. Thus, the growth of mushrooms is not just a reproductive strategy but also a mechanism to sustain and expand the fungal role in decomposition and ecosystem functioning.

Overall, the growth of mushrooms is intimately tied to the fungal role in ecosystem decomposition. By producing mushrooms, fungi ensure the dispersal of spores, enabling them to colonize new substrates and continue breaking down organic matter. This process is essential for nutrient cycling, soil health, and the overall productivity of ecosystems. Without fungi and their mushrooms, decomposition would be far less efficient, leading to nutrient bottlenecks and reduced ecosystem resilience. Understanding this role highlights the importance of fungi as unsung heroes of the natural world.

Discovering Morel Mushrooms: Do They Thrive in New York's Forests?

You may want to see also

Genetic factors influencing mushroom growth

Mushrooms are the fruiting bodies of fungi, and their growth is a complex process influenced by both environmental and genetic factors. At the core of mushroom development lies the genetic blueprint of the fungus, which dictates the timing, structure, and efficiency of fruiting body formation. Genetic factors play a pivotal role in determining whether a fungus will produce mushrooms, how many it will produce, and under what conditions. These factors are encoded in the fungus's DNA and govern the expression of genes involved in various stages of mushroom growth, from initiation to maturation.

One of the key genetic factors influencing mushroom growth is the presence of specific genes that regulate the transition from vegetative growth (mycelium expansion) to reproductive growth (mushroom formation). This transition is often triggered by environmental cues such as changes in light, temperature, humidity, or nutrient availability, but the fungus's genetic makeup determines its responsiveness to these cues. For example, genes involved in the circadian clock and photoreception pathways enable fungi to sense light, a critical factor for mushroom formation in many species. Mutations or variations in these genes can lead to altered fruiting patterns or even the inability to produce mushrooms.

Another genetic factor is the role of mating-type genes in mushroom-forming basidiomycetes. These fungi are often heterothallic, meaning they require two compatible individuals to mate and form mushrooms. The mating-type loci contain genes that determine compatibility, and successful mating triggers the developmental pathways leading to mushroom growth. In species like *Coprinopsis cinerea*, research has shown that specific genes in the mating-type region control the initiation of fruiting body development. Without the proper genetic interaction between compatible partners, mushroom formation is inhibited, highlighting the critical role of genetics in this process.

Genetic regulation of secondary metabolism also influences mushroom growth, as many fungi produce compounds that either promote or inhibit fruiting body development. For instance, genes involved in the biosynthesis of hormones like gibberellins or other signaling molecules can directly impact mushroom formation. In some species, mutations in these genes can lead to dwarfism or the absence of mushrooms. Additionally, genetic variations in genes controlling resource allocation can affect whether a fungus prioritizes mycelial growth or mushroom production, as energy and nutrients are diverted to support the development of fruiting bodies.

Finally, genetic diversity within fungal populations can influence mushroom growth through adaptation to specific environments. Certain genetic variants may confer advantages in particular conditions, such as resistance to pathogens or tolerance to extreme temperatures, which indirectly support mushroom formation. Studies on model fungi like *Schizophyllum commune* have revealed that genetic differences in regulatory networks can lead to variations in fruiting efficiency. Understanding these genetic factors not only sheds light on why fungi grow mushrooms but also has practical applications in agriculture, biotechnology, and conservation efforts aimed at optimizing mushroom yields and preserving fungal biodiversity.

Mastering Mushroom Cultivation: A Guide to Using Agar for Optimal Growth

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Fungi grow mushrooms as reproductive structures to produce and disperse spores, ensuring their survival and propagation.

Mushroom spores are akin to seeds in plants; they allow fungi to spread to new environments, colonize new areas, and continue their life cycle.

No, not all fungi produce mushrooms. Only certain types of fungi, like basidiomycetes and some ascomycetes, develop mushrooms as part of their reproductive strategy.

Mushrooms often appear after rain because moisture triggers the growth of fungal mycelium, which then develops into mushrooms to release spores in favorable conditions.