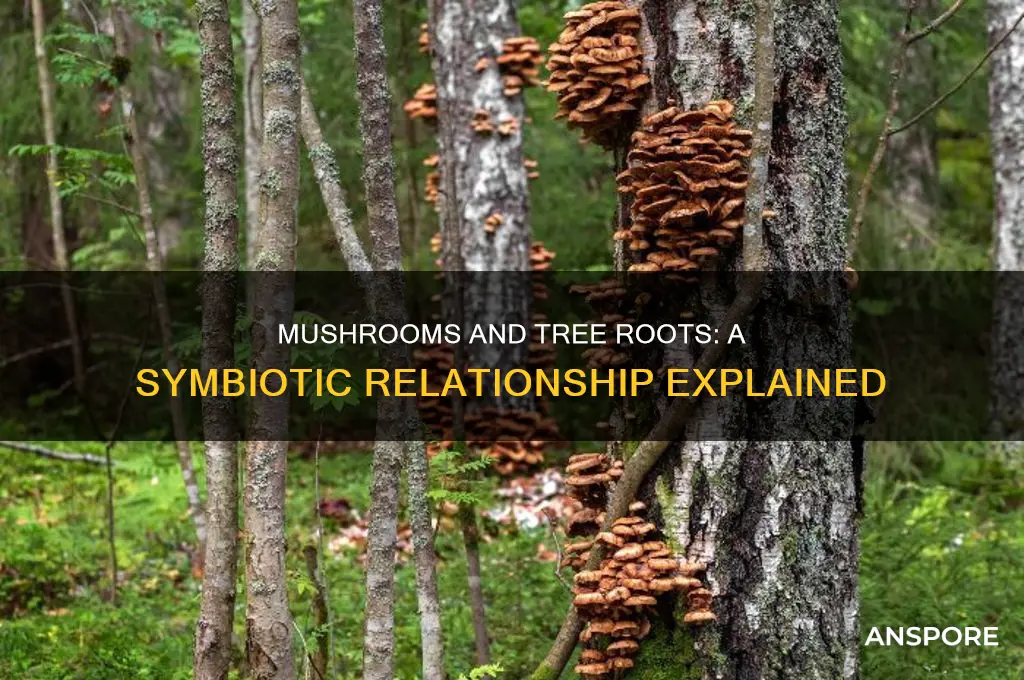

Mushrooms and tree roots share a fascinating symbiotic relationship known as mycorrhiza, where the fungi colonize the roots of trees to form a mutually beneficial partnership. This connection allows mushrooms to access essential nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorus, which are difficult for trees to absorb directly from the soil. In return, the tree roots provide mushrooms with carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis. This interdependence not only enhances the health and growth of both organisms but also plays a crucial role in forest ecosystems by improving soil structure, nutrient cycling, and overall biodiversity. Understanding this relationship sheds light on the intricate ways in which nature fosters cooperation and sustainability.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Nutrient Exchange | Mushrooms (fungi) form mutualistic relationships with tree roots, known as mycorrhizae. Fungi help trees absorb nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen from the soil, which are difficult for trees to access directly. |

| Water Uptake | Mycorrhizal fungi increase the surface area for water absorption, aiding trees in drought conditions. |

| Disease Resistance | Fungi can protect tree roots from pathogens by competing with harmful organisms and producing antimicrobial compounds. |

| Soil Structure | Fungal networks improve soil structure, enhancing aeration and water retention, which benefits both fungi and trees. |

| Carbon Exchange | Trees provide carbohydrates (sugars) to fungi through photosynthesis, which fungi use for energy in return for nutrients. |

| Seedling Survival | Mycorrhizal associations improve the survival and growth rates of tree seedlings, especially in nutrient-poor soils. |

| Ecosystem Connectivity | Fungal networks (mycelium) connect multiple trees, facilitating nutrient and signal exchange between them, known as the "Wood Wide Web." |

| Biodiversity Support | These relationships promote forest health and biodiversity by supporting interconnected ecosystems. |

| Stress Tolerance | Fungi enhance tree resilience to environmental stresses like pollution, salinity, and temperature extremes. |

| Decomposition | Fungi break down organic matter, recycling nutrients back into the soil, which indirectly benefits trees. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Nutrient Exchange: Mushrooms absorb hard-to-get nutrients via tree roots, aiding both organisms’ growth and survival

- Mycorrhizal Symbiosis: Fungi form mutualistic relationships with tree roots, enhancing water and nutrient uptake

- Root Protection: Mushrooms shield tree roots from pathogens and environmental stressors, ensuring tree health

- Carbon Transfer: Trees provide fungi with carbon, while mushrooms help trees access essential minerals

- Ecosystem Balance: This partnership stabilizes forest ecosystems, promoting biodiversity and soil fertility

Nutrient Exchange: Mushrooms absorb hard-to-get nutrients via tree roots, aiding both organisms’ growth and survival

Mushrooms and tree roots engage in a sophisticated nutrient exchange that underscores their interdependence. Mycorrhizal fungi, which form symbiotic relationships with trees, extend their delicate hyphae—filamentous structures far more absorbent than tree roots—into the soil. These hyphae act as microscopic straws, siphoning up nutrients like phosphorus, nitrogen, and micronutrients that are often locked in organic matter or bound to soil particles. Trees, with their limited root absorption capabilities, struggle to access these nutrients alone. This partnership allows mushrooms to secure essential elements while simultaneously enhancing the tree’s nutrient uptake, illustrating a mutualistic system honed by millions of years of coevolution.

Consider the practical implications of this nutrient exchange for forest ecosystems and agriculture. In forests, mycorrhizal networks can transfer up to 50% of the carbon fixed by trees to neighboring plants and fungi, fostering resilience in nutrient-poor soils. For gardeners and farmers, inoculating soil with mycorrhizal fungi can reduce fertilizer needs by 20–30%, as these fungi efficiently mobilize phosphorus—a nutrient often deficient in agricultural soils. For instance, applying *Pisolithus arhizus* (a mycorrhizal fungus) to pine plantations has been shown to increase tree growth by 30% within the first year. This strategy not only conserves resources but also promotes healthier, more sustainable ecosystems.

The nutrient exchange between mushrooms and tree roots is not a one-way transaction; it’s a dynamic dialogue. Trees provide fungi with carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis, which fungi cannot synthesize independently. In return, fungi deliver hard-to-access nutrients, creating a balanced trade. This relationship is particularly critical in stressed environments, such as drought-prone areas, where mycorrhizal networks act as underground pipelines, redistributing water and nutrients to where they’re most needed. Studies show that trees connected via mycorrhizal networks are 40% more likely to survive drought conditions than isolated trees, highlighting the survival advantage of this partnership.

To harness this natural process, landowners and gardeners can take specific steps. First, avoid tilling soil, as it disrupts fungal networks. Instead, use no-till or low-till methods to preserve hyphae. Second, incorporate organic matter like compost or leaf litter, which fungi thrive on, into the soil. Third, select plant species known to form strong mycorrhizal associations, such as oak, pine, or birch trees. For those working with young trees, applying mycorrhizal inoculants at planting time can establish robust fungal networks early, ensuring trees receive adequate nutrients during critical growth stages. By nurturing this symbiotic relationship, we can enhance both plant health and ecosystem productivity.

Mastering Mushroom Gardens: Survival Tips in Grounded's Tiny World

You may want to see also

Mycorrhizal Symbiosis: Fungi form mutualistic relationships with tree roots, enhancing water and nutrient uptake

Beneath the forest floor, a silent partnership thrives: mycorrhizal symbiosis. This ancient alliance between fungi and tree roots is a cornerstone of forest health, where fungi act as subterranean extensions of the tree’s root system. In exchange for carbohydrates produced by the tree through photosynthesis, fungi deliver hard-to-reach nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen, along with water, directly to the tree’s roots. This mutualistic relationship is not just beneficial—it’s often essential for both parties to survive and thrive in nutrient-poor soils.

Consider the practical implications of this symbiosis. For gardeners or foresters, understanding mycorrhizal networks can revolutionize plant care. Inoculating soil with mycorrhizal fungi, such as *Pisolithus arhizus* or *Rhizophagus intraradices*, can significantly enhance the growth of young trees or crops. For instance, studies show that pine seedlings treated with mycorrhizal fungi exhibit up to 30% greater biomass compared to untreated controls. To implement this, mix 1–2 teaspoons of mycorrhizal inoculant per plant hole during planting, ensuring direct contact with the root system. Avoid over-fertilization, as excessive phosphorus can inhibit fungal activity, disrupting the symbiosis.

The efficiency of mycorrhizal networks lies in their structure. Fungal hyphae—thread-like structures—can extend far beyond the reach of tree roots, increasing the soil volume accessible to the tree by up to 100-fold. This is particularly critical in arid or nutrient-depleted environments, where trees might otherwise struggle to survive. For example, in boreal forests, mycorrhizal fungi help spruce and pine trees access nutrients locked in organic matter, ensuring their resilience in harsh conditions. This adaptability highlights why mycorrhizal symbiosis is a key focus in reforestation efforts, especially in degraded landscapes.

However, this relationship is not without vulnerabilities. Climate change, soil disturbance, and fungicides can disrupt mycorrhizal networks, weakening both fungi and trees. In agricultural settings, tilling and chemical fertilizers often sever fungal hyphae, reducing their effectiveness. To preserve this symbiosis, adopt no-till practices, use organic fertilizers, and avoid broad-spectrum fungicides. For forest restoration, prioritize native tree species and fungi, as their co-evolved relationships are often more efficient than introduced pairings.

In essence, mycorrhizal symbiosis is a testament to nature’s ingenuity—a partnership that has shaped ecosystems for millions of years. By harnessing this relationship, we can foster healthier forests, more productive gardens, and resilient landscapes. Whether you’re a gardener, forester, or conservationist, understanding and nurturing this underground alliance is a powerful step toward sustainable stewardship.

Mastering Mushroom Spikes: Creative Uses and Practical Tips for Gardeners

You may want to see also

Root Protection: Mushrooms shield tree roots from pathogens and environmental stressors, ensuring tree health

Beneath the forest floor, a silent alliance thrives between mushrooms and tree roots, a partnership rooted in mutual defense. Mushrooms, through their intricate mycelial networks, act as sentinels, shielding tree roots from pathogens like *Phytophthora* and *Armillaria*, which can cause root rot and decay. These fungal networks secrete antibiotics and enzymes that inhibit harmful microbes, creating a protective barrier around the roots. For instance, mycorrhizal fungi associated with oak trees have been observed to reduce infection rates by up to 70%, ensuring the longevity and health of their host trees.

Consider this protective mechanism as a natural immunization system. Just as vaccines prime the human immune system, mycelial networks fortify tree roots against environmental stressors like drought and salinity. During dry periods, mushrooms help roots retain moisture by improving soil structure and water absorption. In saline environments, they mitigate salt toxicity by regulating ion uptake. A study on pine trees in arid regions found that mycorrhizal associations increased water uptake efficiency by 40%, demonstrating their role as environmental buffers.

To harness this protective power, forest managers and gardeners can introduce beneficial mushroom species like *Laccaria bicolor* or *Pisolithus arhizus* into soil ecosystems. These fungi form symbiotic relationships with tree roots, enhancing their resilience. For young saplings, inoculating the root zone with mycorrhizal spores during planting can establish a protective network early. For mature trees, applying mycelium-rich compost around the base annually can reinforce root health. Avoid chemical fertilizers, as they disrupt fungal communities, weakening this natural defense system.

Comparing this relationship to human infrastructure, mushrooms function like a living shield, akin to how coral reefs protect coastlines from erosion. Just as reefs absorb wave energy, mycelial networks absorb and neutralize threats to tree roots. This analogy underscores the importance of preserving fungal biodiversity, as its loss would leave trees vulnerable to pathogens and stressors, much like a coastline without its reef. By understanding and supporting this symbiotic bond, we can ensure the health of forests and, by extension, the ecosystems they sustain.

Savor the Flavor: Beer-Braised Baby Portobello Mushrooms Recipe Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$13.99 $17.99

Carbon Transfer: Trees provide fungi with carbon, while mushrooms help trees access essential minerals

Beneath the forest floor, a silent exchange occurs, one that sustains both trees and fungi in a delicate balance. Trees, through photosynthesis, produce carbon-rich sugars, a portion of which they channel into their roots. Here, fungi await, their mycelial networks intertwined with tree roots in a symbiotic partnership known as mycorrhiza. This carbon, essential for fungal growth and metabolism, is transferred from tree to fungus, fueling the latter’s expansive underground network. Without this carbon source, many fungi would struggle to survive, highlighting the tree’s role as a primary energy provider in this subterranean economy.

In return, mushrooms—the fruiting bodies of these fungi—play a critical role in enhancing the tree’s mineral uptake. Fungal mycelium, with its vast surface area, can access nutrients like phosphorus, nitrogen, and micronutrients that tree roots alone cannot efficiently absorb. For instance, phosphorus, vital for tree growth, is often locked in soil compounds inaccessible to roots. Fungi secrete enzymes that break these compounds down, releasing phosphorus in a form trees can use. Studies show that up to 80% of a tree’s phosphorus can come from this fungal partnership. This mineral exchange not only boosts tree health but also improves their resilience to stressors like drought or disease.

Consider this practical application: in reforestation efforts, introducing mycorrhizal fungi alongside saplings can significantly enhance tree survival rates. For example, inoculating pine seedlings with *Pisolithus arhizus*, a common mycorrhizal fungus, has been shown to increase phosphorus uptake by 50% and improve seedling growth by 30%. Gardeners and foresters can replicate this by sourcing mycorrhizal inoculants and applying them to root zones during planting. However, caution is advised: not all fungi form mycorrhizal relationships, and mismatching species can yield poor results. Always pair fungi native to the region and compatible with the tree species in question.

This carbon-for-minerals trade is not just a biological curiosity but a cornerstone of forest ecosystems. It underscores the interdependence of life forms, where one organism’s waste becomes another’s resource. For those looking to nurture their own green spaces, understanding this dynamic can transform how we approach planting and soil management. By fostering healthy mycorrhizal networks, we can create more resilient, self-sustaining ecosystems—whether in a backyard garden or a sprawling forest. The takeaway is clear: in the partnership between trees and fungi, both parties thrive, proving that collaboration, even in the microbial world, is key to survival.

Unlocking Flavor: Creative Ways to Use Porcini Mushroom Powder

You may want to see also

Ecosystem Balance: This partnership stabilizes forest ecosystems, promoting biodiversity and soil fertility

Beneath the forest floor, a silent alliance thrives between mushrooms and tree roots, a partnership known as mycorrhiza. This symbiotic relationship is not merely a biological curiosity; it is the linchpin of ecosystem balance. Mushrooms, through their intricate mycelial networks, act as nature’s internet, connecting trees in a shared economy of nutrients. In exchange for carbohydrates from trees, mushrooms provide essential minerals like phosphorus and nitrogen, which tree roots struggle to access alone. This exchange stabilizes forest ecosystems by ensuring that even the weakest saplings can thrive, fostering resilience against pests, diseases, and climate stress.

Consider the practical implications of this partnership for forest management. When reforesting degraded lands, introducing mycorrhizal fungi alongside saplings can increase survival rates by up to 80%. For instance, in the Pacific Northwest, Douglas firs inoculated with native *Laccaria* fungi show faster growth and higher resistance to drought. This method is not just ecologically sound but cost-effective, reducing the need for chemical fertilizers. Land managers can amplify this effect by preserving deadwood and leaf litter, which serve as fungal habitats, ensuring the mycelial network remains intact.

The role of this partnership in promoting biodiversity cannot be overstated. By enhancing tree health, mycorrhizal fungi create a habitat mosaic that supports a wide array of species. For example, a single fungal network can connect dozens of tree species, facilitating nutrient transfer between them. This interconnectedness allows for the coexistence of shade-tolerant and light-demanding species, increasing forest complexity. In turn, this diversity attracts insects, birds, and mammals, creating a thriving ecosystem. A study in the Amazon found that areas with robust mycorrhizal networks hosted 25% more bird species than areas with weaker fungal connections.

Soil fertility is another critical benefit of this alliance. Mushrooms break down organic matter, releasing nutrients that would otherwise remain locked in decaying wood or leaves. This process not only feeds trees but also enriches the soil for other plants, from wildflowers to ferns. In agricultural settings, mimicking this natural process through fungal inoculation can reduce soil erosion by 30% and improve water retention. Gardeners and farmers can replicate this by composting with mushroom-rich materials or using mycorrhizal inoculants when planting crops, fostering healthier soils without synthetic inputs.

Ultimately, the partnership between mushrooms and tree roots is a masterclass in ecological interdependence. It demonstrates how cooperation at the microbial level can sustain entire ecosystems, from the soil microbes to the canopy birds. By understanding and protecting this relationship, we can restore degraded landscapes, enhance biodiversity, and secure the fertility of our soils for future generations. This is not just a biological phenomenon—it is a blueprint for sustainable coexistence.

Unlocking Nature's Gifts: Practical Uses for Polypore Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Mushrooms often form symbiotic relationships with tree roots through mycorrhizal associations, where the fungus helps the tree absorb nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen, while the tree provides the fungus with carbohydrates.

Mushrooms benefit from tree roots by receiving sugars and other organic compounds produced by the tree through photosynthesis, which the fungus cannot produce on its own.

Tree roots benefit from mushrooms because the fungal network increases the root’s surface area, enhancing nutrient and water absorption, and improving the tree’s overall health and resilience.

Yes, some mushrooms can grow without tree roots, either as saprotrophs (breaking down dead organic matter) or parasites, but many species rely on mycorrhizal relationships with trees for survival and growth.