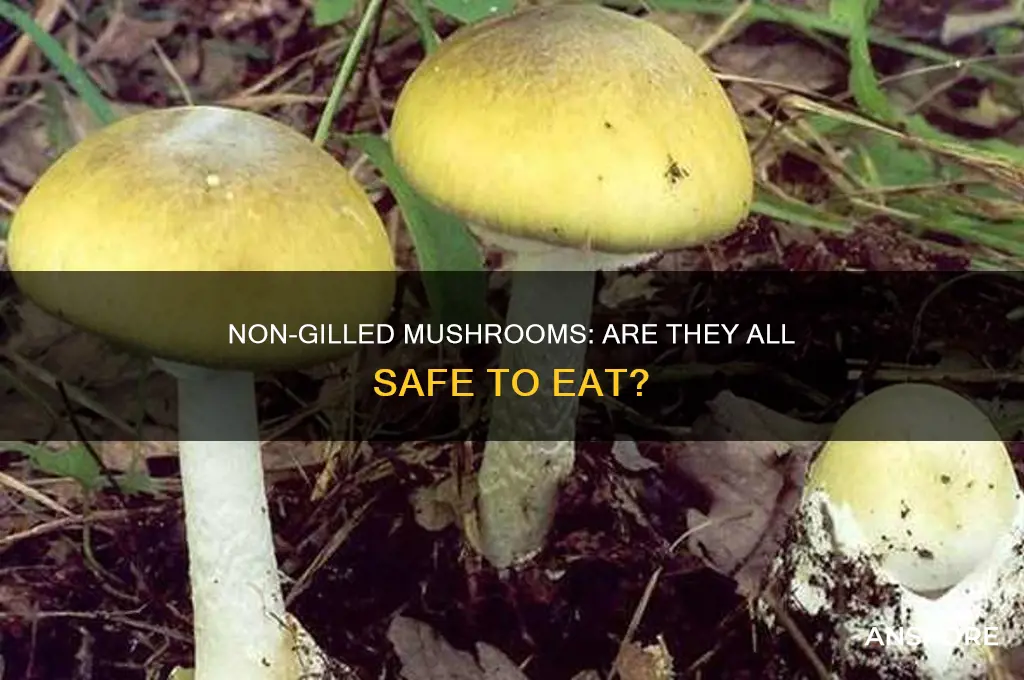

The question of whether all non-gilled mushrooms are safe to eat is a common yet complex one, as it hinges on the vast diversity of fungal species. While it’s true that many non-gilled mushrooms, such as puffballs, chanterelles, and morels, are edible and even prized in culinary traditions, this generalization can be misleading. Non-gilled mushrooms encompass a wide range of species, some of which are toxic or poisonous, such as certain Amanita species or false morels. Identifying edible mushrooms requires precise knowledge of their characteristics, habitat, and potential look-alikes, as relying solely on the absence of gills is insufficient. Therefore, caution and expert guidance are essential when foraging, as misidentification can lead to serious health risks.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| General Safety | Not all non-gilled mushrooms are safe to eat. While some are edible, others can be toxic or poisonous. |

| Common Non-Gilled Mushrooms | Examples include puffballs, chanterelles, morels, and coral mushrooms. |

| Toxic Non-Gilled Mushrooms | Examples include Amanita species (e.g., Amanita ocreata), false morels, and some species of coral mushrooms. |

| Key Identification Features | Non-gilled mushrooms may have pores, spines, folds, or other structures instead of gills. Proper identification is crucial. |

| Edible Species | Many non-gilled mushrooms, like chanterelles and true morels, are highly prized for their culinary value. |

| Poisonous Look-Alikes | Some toxic mushrooms, such as false morels, resemble edible non-gilled species, making accurate identification essential. |

| Symptoms of Poisoning | Symptoms from toxic non-gilled mushrooms can range from mild gastrointestinal distress to severe organ failure or death. |

| Expert Guidance | Always consult a mycologist or use a reliable field guide before consuming wild mushrooms. |

| Cooking Precautions | Proper cooking can reduce toxins in some edible non-gilled mushrooms, but this does not apply to all species. |

| Foraging Risks | Misidentification is a significant risk when foraging for non-gilled mushrooms, as many toxic species lack gills but still pose dangers. |

Explore related products

$7.62 $14.95

What You'll Learn

- False Morels vs. True Morels: Identifying deadly false morels from edible true morels requires careful examination of features

- Lactarius Species: Some milk-cap mushrooms are toxic, while others are edible after proper preparation

- Amanita Lookalikes: Non-gilled amanitas like the destroying angel are deadly, despite lacking gills

- Chanterelle Safety: True chanterelles are safe, but toxic lookalikes like jack-o’-lanterns must be avoided

- Boletus Edibility: Most boletes are edible, but some cause gastrointestinal distress or are poisonous raw

False Morels vs. True Morels: Identifying deadly false morels from edible true morels requires careful examination of features

When exploring the question of whether all non-gilled mushrooms are safe to eat, it becomes crucial to distinguish between false morels and true morels, as this differentiation can mean the difference between a delicious meal and a potentially deadly encounter. False morels, belonging to the genus *Gyromitra*, contain a toxin called gyromitrin, which can cause severe gastrointestinal distress, neurological symptoms, and even organ failure if consumed in significant quantities. True morels, on the other hand, are highly prized edible fungi in the genus *Morchella*, known for their honeycomb-like caps and earthy flavor. Identifying these two types of mushrooms requires careful examination of their physical features.

One of the most noticeable differences between false and true morels is their cap structure. True morels have a distinctly honeycomb or sponge-like appearance, with pits and ridges that create a clearly defined, hollow interior. Their caps are typically attached to the stem at the base, giving them a more uniform, conical, or oval shape. False morels, in contrast, often have a more brain-like, wrinkled, or folded appearance, with a less organized structure. Their caps may appear more rounded or irregular and are often loosely attached to the stem, sometimes even hanging freely. This difference in cap morphology is a key initial indicator when distinguishing between the two.

The stem structure also provides important clues. True morels have a hollow stem that is typically lighter in color and smoothly integrates with the cap. False morels often have a more substantial, fleshy stem that may be partially or fully filled, and it can be darker or more reddish in color. Additionally, false morels sometimes exhibit a brittle texture when broken, whereas true morels tend to have a more elastic or flexible stem. Examining the stem in conjunction with the cap can help confirm the identification.

Color is another distinguishing feature, though it should be used cautiously as it can vary depending on species and environmental factors. True morels are generally tan, brown, gray, or yellow, with a relatively consistent color throughout. False morels may display darker, reddish-brown, or even blackish hues, particularly on the stem or cap folds. However, color alone is not a definitive identifier, as some true morels can also appear darker. Therefore, it should be considered alongside other characteristics.

Finally, habitat and seasonality can provide additional context. True morels typically fruit in spring and are often found in wooded areas, particularly near deciduous trees like ash, elm, and oak. False morels may also appear in spring but can sometimes be found earlier or later in the season, depending on the region. They are often associated with coniferous forests. While habitat and timing can offer clues, they should not replace a thorough physical examination of the mushroom.

In conclusion, identifying deadly false morels from edible true morels requires a meticulous approach, focusing on cap structure, stem characteristics, color, and habitat. While true morels are a safe and delicious delicacy, false morels pose a significant risk due to their toxic compounds. Foraging for morels should always be accompanied by proper education and, when in doubt, consultation with an expert. Not all non-gilled mushrooms are safe to eat, and the distinction between these two types underscores the importance of accurate identification in mushroom foraging.

Pregnancy and Mushrooms: Safe to Eat or Best Avoided?

You may want to see also

Lactarius Species: Some milk-cap mushrooms are toxic, while others are edible after proper preparation

The Lactarius species, commonly known as milk-cap mushrooms, present a fascinating yet complex group within the fungal kingdom when considering edibility. These mushrooms are characterized by their unique feature of exuding a milky latex when injured, a trait that gives them their name. However, this distinctive characteristic does not provide a straightforward answer to their safety for consumption. Among the Lactarius species, there is a significant variation in toxicity, making it crucial for foragers to approach them with caution and knowledge.

While some milk-cap mushrooms are indeed toxic and should be avoided, others can be safely consumed after proper preparation. The key lies in accurate identification, as the Lactarius genus comprises hundreds of species, each with its own set of characteristics. For instance, *Lactarius deliciosus*, commonly known as the saffron milk cap, is a highly prized edible species in many parts of the world. It is known for its vibrant orange color and distinctive flavor, making it a sought-after ingredient in culinary traditions, especially in Europe and North America. However, even with this species, proper preparation is essential, as consuming it raw or undercooked can lead to gastrointestinal discomfort.

On the other hand, some Lactarius species are toxic and can cause various adverse reactions. *Lactarius torminosus*, for example, contains toxins that can lead to severe gastrointestinal symptoms if consumed. This species is often referred to as the "wolftail milk cap" and is known for its distinctive woolly stem and orange-brown cap. Foragers must be able to distinguish between similar-looking species to avoid accidental poisoning. The toxicity of Lactarius mushrooms is often associated with their latex, which can be irritating or even harmful when ingested.

Proper preparation methods are vital when dealing with edible Lactarius species. These mushrooms typically require thorough cooking to neutralize any potential toxins and to enhance their flavor. Common preparation techniques include sautéing, boiling, or drying. Boiling is particularly effective in removing the milky latex, which can have a bitter taste and may cause digestive issues. After boiling, the mushrooms can be used in various dishes, adding a unique, rich flavor. It is worth noting that some people may still experience mild reactions even with properly prepared milk-cap mushrooms, so moderation is advised.

In the context of non-gilled mushrooms, the Lactarius species highlight the importance of detailed knowledge and caution. While some non-gilled mushrooms are safe and delicious, the milk-caps demonstrate that edibility is not a simple matter of morphology. Foragers and mushroom enthusiasts should invest time in learning the specific characteristics, habitats, and preparation methods for each species they intend to consume. This approach ensures a safe and enjoyable experience when exploring the diverse world of mushrooms beyond the typical gilled varieties.

Delicious Pairings: Perfect Sides to Serve with Stuffed Portobello Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Amanita Lookalikes: Non-gilled amanitas like the destroying angel are deadly, despite lacking gills

When exploring the question of whether all non-gilled mushrooms are safe to eat, it’s crucial to address the dangers posed by certain Amanita species, particularly those that lack gills but are still highly toxic. Among these, the *Destroying Angel* (species like *Amanita bisporigera* and *Amanita ocreata*) stands out as a prime example of a non-gilled mushroom that is deadly if ingested. Despite their lack of gills, these mushrooms share the same lethal amatoxins found in their gilled relatives, such as the infamous *Amanita phalloides* (Death Cap). This fact underscores the importance of not assuming safety based solely on the absence of gills.

Amanita lookalikes, including the Destroying Angel, often resemble benign species like the puffball or other non-gilled mushrooms, which can mislead foragers. The Destroying Angel, for instance, has a smooth, white cap and a bulbous base, features that might appear innocuous to the untrained eye. However, its clean, non-gilled appearance does not diminish its toxicity. Ingesting even a small amount can lead to severe liver and kidney damage, often resulting in death if not treated promptly. This highlights the need for precise identification beyond superficial characteristics like gills.

Another critical point is that non-gilled Amanitas often grow in similar habitats to edible mushrooms, such as forests and grassy areas, increasing the risk of accidental collection. Foragers must be aware that the absence of gills does not automatically classify a mushroom as safe. Instead, they should focus on identifying key features like the volva (a cup-like structure at the base) and the presence of white spores, both of which are hallmark traits of many toxic Amanitas. These characteristics are more reliable indicators of danger than the presence or absence of gills.

To avoid confusion with Amanita lookalikes, it’s essential to educate oneself on the specific traits of toxic species. For example, the Destroying Angel’s all-white appearance and lack of gills might tempt foragers, but its volva and spore print are telltale signs of its toxicity. Additionally, relying on field guides, expert advice, and spore-printing techniques can help distinguish dangerous Amanitas from safe non-gilled mushrooms. The mantra “when in doubt, throw it out” should always be followed, as misidentification can have fatal consequences.

In conclusion, the belief that non-gilled mushrooms are universally safe is a dangerous misconception, particularly when it comes to Amanita lookalikes like the Destroying Angel. These mushrooms defy the gill-based safety assumption by harboring deadly toxins despite their smooth, gill-less structure. Foragers must prioritize detailed identification, focusing on features like the volva, spore color, and habitat, rather than relying on the presence or absence of gills. Awareness and caution are paramount when dealing with mushrooms, as even seemingly harmless non-gilled species can pose a significant threat.

Do Vegans Eat Mushrooms? Exploring Plant-Based Dietary Choices

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Chanterelle Safety: True chanterelles are safe, but toxic lookalikes like jack-o’-lanterns must be avoided

When it comes to mushroom foraging, the question of safety is paramount, especially for non-gilled varieties like chanterelles. True chanterelles (Cantharellus cibarius and related species) are indeed safe to eat and highly prized for their fruity aroma and delicate flavor. These mushrooms are characterized by their forked, wrinkled gills (technically ridges) that run down their stem, a golden-yellow color, and a chewy yet tender texture. However, their safety hinges on accurate identification, as several toxic lookalikes can easily deceive even experienced foragers.

One of the most notorious toxic doppelgängers is the jack-o’lantern mushroom (Omphalotus olearius or Omphalotus illudens), which grows in clusters on wood and has a similar bright orange-yellow hue. Unlike chanterelles, jack-o’lanterns have true gills that are sharply defined and not forked. Ingesting these mushrooms can cause severe gastrointestinal distress, including vomiting, diarrhea, and dehydration. Another dangerous lookalike is the false chanterelle (Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca), which has thinner, more widely spaced gills and lacks the apricot scent of true chanterelles. While not as toxic as jack-o’lanterns, false chanterelles can still cause discomfort.

To ensure chanterelle safety, foragers must focus on key identification features. True chanterelles have a forked gill structure, a smooth cap with wavy edges, and a faint fruity or apricot-like scent. They typically grow in woodland areas, often near coniferous trees. In contrast, toxic lookalikes like jack-o’lanterns grow in clusters on wood and lack the forked gills and fruity aroma. Always examine the mushroom’s habitat, gill structure, and scent before harvesting.

It’s crucial to remember that not all non-gilled mushrooms are safe to eat, and chanterelles are no exception when it comes to lookalikes. While true chanterelles are a culinary delight, misidentification can lead to serious health risks. If you’re unsure, consult a field guide, join a local mycological society, or seek advice from an expert. When in doubt, throw it out—never consume a mushroom unless you’re 100% certain of its identity.

Finally, chanterelle safety also involves proper preparation. Even true chanterelles should be thoroughly cleaned to remove dirt and debris, and they should always be cooked before consumption, as raw mushrooms can be difficult to digest. By combining careful identification with safe handling practices, foragers can enjoy the unique flavor of chanterelles without risking their health. Always prioritize caution and knowledge when foraging for wild mushrooms.

Do Whitetail Deer Eat Morel Mushrooms? Uncovering the Truth

You may want to see also

Boletus Edibility: Most boletes are edible, but some cause gastrointestinal distress or are poisonous raw

The Boletus genus, commonly known as boletes, is a diverse group of mushrooms that has long fascinated foragers and mycologists alike. Boletus edibility is a topic of significant interest, as these fungi are generally considered more approachable than gilled mushrooms due to their distinctive porous undersides. While it’s true that most boletes are edible, this generalization comes with important caveats. Not all boletes are safe to consume, and some can cause gastrointestinal distress or are poisonous when eaten raw. This highlights the critical need for accurate identification and preparation before consuming any wild mushroom, even within this seemingly safer genus.

One of the key challenges in assessing Boletus edibility is the existence of species that resemble their edible counterparts but are toxic. For instance, the *Boletus satanas* (Devil’s Bolete) is a well-known example of a bolete that can cause severe gastrointestinal symptoms if consumed. Its striking appearance, with a pale cap and bulky stature, might deceive inexperienced foragers. Similarly, some boletes, like *Boletus luridus* (Reddish Bolete), are edible when cooked but can be toxic when raw or consumed with alcohol. These exceptions underscore the importance of thorough cooking and proper identification, as raw consumption or misidentification can lead to unpleasant or even dangerous outcomes.

Another factor to consider is the variability in individual tolerance to certain boletes. While some species are widely regarded as edible, such as *Boletus edulis* (Porcini), others may cause mild to moderate gastrointestinal distress in sensitive individuals. For example, *Boletus reticulatus* (Early Bolete) is generally considered edible but has been reported to cause digestive issues in some people. This variability emphasizes the need for caution, especially when trying a bolete species for the first time. Starting with a small portion and observing for adverse reactions is a prudent approach.

Geographic location also plays a role in Boletus edibility. Some boletes that are safe in one region may have toxic look-alikes in another. For instance, in North America, *Boletus frostii* (Frost’s Bolete) is edible, but it closely resembles *Boletus pulcherrimus*, which can cause gastrointestinal distress. In Europe, *Boletus rhodoxanthus* is edible, but it can be confused with *Boletus luridus*, which is toxic when raw. This regional variability further complicates identification and reinforces the need for local knowledge and expert guidance.

In conclusion, while most boletes are edible, the statement that all non-gilled mushrooms are safe to eat is a dangerous oversimplification. The Boletus genus contains exceptions that can cause harm, either through toxicity or individual sensitivity. Proper identification, thorough cooking, and awareness of regional variations are essential for safely enjoying boletes. When in doubt, consulting a field guide, mycologist, or experienced forager is always the best course of action. The allure of boletes lies in their diversity and culinary potential, but their safe consumption requires respect for their complexity and the willingness to learn and exercise caution.

Can Rabbits Safely Eat Mushrooms? A Complete Guide for Owners

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all non-gilled mushrooms are safe to eat. While some, like chanterelles and morels, are edible and prized, others, such as certain species of Amanita or false morels, are toxic and can cause severe illness or death.

Identifying safe non-gilled mushrooms requires knowledge of specific characteristics, such as spore color, stem features, and habitat. Always consult a reliable field guide or expert, and never eat a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity.

Most young, white-interior puffballs (like *Calvatia* species) are edible, but older specimens or those with colored interiors can be toxic. Additionally, some poisonous mushrooms, like young Amanitas, can resemble puffballs, so proper identification is crucial.

It is generally not recommended to eat any wild mushrooms raw, including non-gilled varieties, as they may contain toxins or hard-to-digest compounds. Cooking mushrooms properly helps break down these substances and makes them safer to consume.

Store-bought mushrooms, such as shiitake or oyster mushrooms, are cultivated and safe to eat. However, wild-harvested non-gilled mushrooms sold in markets may not always be properly identified, so caution is advised unless sourced from a trusted supplier.