The question of whether all spore-forming bacteria are gram-positive is a common one in microbiology, often arising from the well-known examples of spore-forming pathogens like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, which are indeed gram-positive. However, this assumption overlooks the diversity of spore-forming bacteria across different taxonomic groups. While the majority of spore-forming bacteria, including those in the Firmicutes phylum, are gram-positive, there are notable exceptions. For instance, some gram-negative bacteria, such as those in the genus *Desulfotomaculum* (from the phylum Firmicutes) and certain members of the *Myxobacteria*, can also form spores. Additionally, the discovery of spore-forming capabilities in some gram-negative bacteria challenges the traditional association of spore formation exclusively with gram-positive organisms. Thus, while gram-positive bacteria dominate the spore-forming category, it is not accurate to generalize that all spore-forming bacteria are gram-positive.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Are all spore-forming bacteria Gram-positive? | No, not all spore-forming bacteria are Gram-positive. |

| Examples of Gram-positive spore-formers | Bacillus spp., Clostridium spp., Staphylococcus spp. (some strains). |

| Examples of Gram-negative spore-formers | Sporomusa spp., Desulfotomaculum spp., Seliberia spp. |

| Gram staining result | Gram-positive: Retain crystal violet stain; Gram-negative: Do not retain crystal violet stain. |

| Cell wall structure | Gram-positive: Thick peptidoglycan layer; Gram-negative: Thin peptidoglycan layer with outer membrane. |

| Spore formation location | Endospores formed within the bacterial cell. |

| Spore resistance | Highly resistant to heat, radiation, desiccation, and chemicals. |

| Ecological niches | Diverse habitats, including soil, water, and extreme environments. |

| Medical relevance | Some are pathogens (e.g., Clostridium botulinum), while others are beneficial (e.g., Bacillus subtilis). |

| Taxonomic diversity | Spore formation is found in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative phyla, though less common in Gram-negatives. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Gram-Positive vs. Gram-Negative Spore Formers

Spore-forming bacteria are a unique group of microorganisms capable of producing highly resistant endospores, allowing them to survive extreme conditions. While it’s commonly assumed that all spore-forming bacteria are Gram-positive, this is a misconception. Gram-negative spore formers, though less common, do exist, challenging the notion that spore formation is exclusive to Gram-positive species. This distinction is crucial for understanding bacterial classification, pathogenicity, and treatment strategies.

Analyzing the Gram Stain Divide

The Gram stain, a fundamental microbiological technique, differentiates bacteria based on cell wall structure. Gram-positive bacteria retain crystal violet dye due to their thick peptidoglycan layer, while Gram-negative bacteria lose it because of their thinner peptidoglycan and additional outer membrane. Most spore-forming bacteria, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, are Gram-positive. However, exceptions like *Xenorhabdus* and *Photorhabdus*, both Gram-negative, demonstrate that spore formation is not limited to Gram-positive species. This highlights the complexity of bacterial adaptations and the need to avoid oversimplification in classification.

Practical Implications for Identification and Treatment

Distinguishing between Gram-positive and Gram-negative spore formers is essential for clinical and industrial applications. Gram-positive spores, such as those of *Bacillus anthracis* (causative agent of anthrax), are typically susceptible to antibiotics targeting cell wall synthesis, like penicillin. In contrast, Gram-negative spore formers may require broader-spectrum antibiotics due to their outer membrane, which confers additional resistance. For example, *Xenorhabdus* species, often associated with nematodes, may necessitate treatment with antibiotics like tetracyclines or aminoglycosides. Understanding this difference ensures effective therapeutic interventions.

Comparative Resilience of Spores

Both Gram-positive and Gram-negative spore formers produce spores with remarkable resilience, but their mechanisms of survival can differ. Gram-positive spores, such as those of *Clostridium botulinum*, are known for their ability to withstand high temperatures, radiation, and desiccation. Gram-negative spores, while less studied, exhibit similar durability but may have unique protective mechanisms tied to their outer membrane. For instance, *Photorhabdus* spores are often found in symbiotic relationships with insects, suggesting specialized adaptations for survival in specific environments. This comparative resilience underscores the evolutionary advantages of spore formation across Gram categories.

Takeaway for Researchers and Practitioners

While Gram-positive bacteria dominate the spore-forming landscape, the existence of Gram-negative spore formers expands our understanding of bacterial diversity. Researchers must remain vigilant in identifying and characterizing these exceptions to avoid misclassification. Clinicians should consider the Gram status of spore-forming pathogens when selecting antibiotics, as it directly impacts treatment efficacy. For industries like food safety and biotechnology, recognizing the full spectrum of spore formers ensures better contamination control and process optimization. In essence, the Gram-positive vs. Gram-negative spore former debate is not just academic—it has tangible implications for science and practice.

Unveiling the Spore-Producing Structures: A Comprehensive Guide to Identification

You may want to see also

Bacillus and Clostridium: Key Examples

Spore-forming bacteria are a fascinating subset of microorganisms, capable of surviving extreme conditions by forming highly resistant spores. Among these, Bacillus and Clostridium stand out as two of the most well-known genera. Both are gram-positive, rod-shaped bacteria, but their characteristics, habitats, and impacts on human health differ significantly. Understanding these differences is crucial for fields like medicine, food safety, and biotechnology.

Bacillus species are ubiquitous in soil and water, thriving in diverse environments. One of the most notable examples is *Bacillus anthracis*, the causative agent of anthrax. This bacterium forms spores that can remain dormant in soil for decades, posing a risk to livestock and humans. Another important species is *Bacillus subtilis*, widely used in biotechnology for enzyme production and as a probiotic in animal feed. Unlike *B. anthracis*, *B. subtilis* is considered non-pathogenic and safe for industrial applications. The ability of *Bacillus* spores to withstand heat and desiccation makes them a challenge in food preservation, necessitating sterilization techniques like autoclaving at 121°C for 15–20 minutes to ensure complete inactivation.

In contrast, Clostridium species are primarily anaerobic and often associated with clinical infections. *Clostridium botulinum*, for instance, produces botulinum toxin, one of the deadliest substances known, which causes botulism. Even small amounts of this toxin (as little as 1 nanogram per kilogram of body weight) can be fatal. Another notorious species is *Clostridium difficile*, a leading cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and colitis, particularly in hospitalized patients over 65 years old. Unlike *Bacillus*, *Clostridium* spores are commonly found in the gastrointestinal tract and soil, and their anaerobic nature requires specific conditions for growth and toxin production.

Comparing these two genera highlights their distinct ecological niches and pathogenic potentials. While *Bacillus* species are primarily environmental and often beneficial in industrial settings, *Clostridium* species are more clinically significant, causing severe and sometimes life-threatening infections. Both, however, share the gram-positive trait and the ability to form spores, underscoring the importance of spore-forming bacteria in both beneficial and harmful contexts.

Practical tips for managing these bacteria include proper hygiene, especially in healthcare settings, to prevent *C. difficile* infections. For food safety, thorough cooking (ensuring internal temperatures of 75°C or higher) can destroy *C. botulinum* spores and toxins. In industrial applications, selecting non-pathogenic *Bacillus* strains like *B. subtilis* can maximize benefits while minimizing risks. By understanding the unique characteristics of *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, we can better navigate their roles in health, industry, and the environment.

Is Milky Spore Safe for Dogs? A Pet Owner's Guide

You may want to see also

Exceptions: Gram-Negative Spore-Forming Bacteria

While the majority of spore-forming bacteria are indeed Gram-positive, a small but significant group defies this generalization: Gram-negative spore-formers. These exceptions challenge our understanding of bacterial classification and highlight the remarkable diversity within the microbial world.

The Outliers: Meet the Gram-Negative Spore-Formers

The genus *Bacillus* and its close relatives, traditionally associated with Gram-positive spore formation, have long dominated our understanding. However, a handful of Gram-negative bacteria have evolved the ability to produce spores, albeit with distinct characteristics. *Halothermothrix orenii*, a thermophilic bacterium thriving in salty environments, stands out as a prime example. This organism, classified within the phylum *Firmicutes*, forms spores encased in a unique, multi-layered structure, showcasing the ingenuity of bacterial adaptation.

Seliberia species, found in diverse habitats including soil and aquatic environments, further expand the spectrum of Gram-negative spore-formers. Their spores, while less studied than those of H. orenii, contribute to the growing recognition of this exceptional group.

Implications and Significance:

The existence of Gram-negative spore-formers has profound implications. Firstly, it challenges the traditional Gram stain as a definitive classifier, emphasizing the need for a more nuanced approach to bacterial identification. Secondly, understanding these exceptions expands our knowledge of spore formation mechanisms, potentially leading to novel biotechnological applications. For instance, the unique spore structure of *H. orenii* could inspire the development of more resilient spore-based delivery systems for probiotics or enzymes.

Practical Considerations:

Identifying Gram-negative spore-formers requires careful laboratory techniques. While the Gram stain remains a valuable initial tool, additional tests, such as spore staining and molecular methods like PCR, are crucial for accurate identification. Researchers and clinicians should be aware of these exceptions to avoid misdiagnosis and ensure appropriate treatment strategies.

In conclusion, the discovery of Gram-negative spore-forming bacteria expands our understanding of microbial diversity and challenges established classifications. These exceptions, though rare, highlight the remarkable adaptability of bacteria and open up exciting avenues for further research and potential applications.

How Do Ferns Reproduce? Unveiling the Mystery of Fern Spores

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spore Formation Mechanisms in Bacteria

Spore formation, or sporulation, is a survival mechanism employed by certain bacteria to endure harsh environmental conditions. This process involves a complex series of morphological and biochemical changes, culminating in the production of a highly resistant spore. Contrary to the assumption that all spore-forming bacteria are Gram-positive, the reality is more nuanced. While the majority of known spore-forming bacteria, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, are indeed Gram-positive, recent discoveries have identified spore-forming species within the Gram-negative phylum *Myxococcota*, challenging traditional classifications.

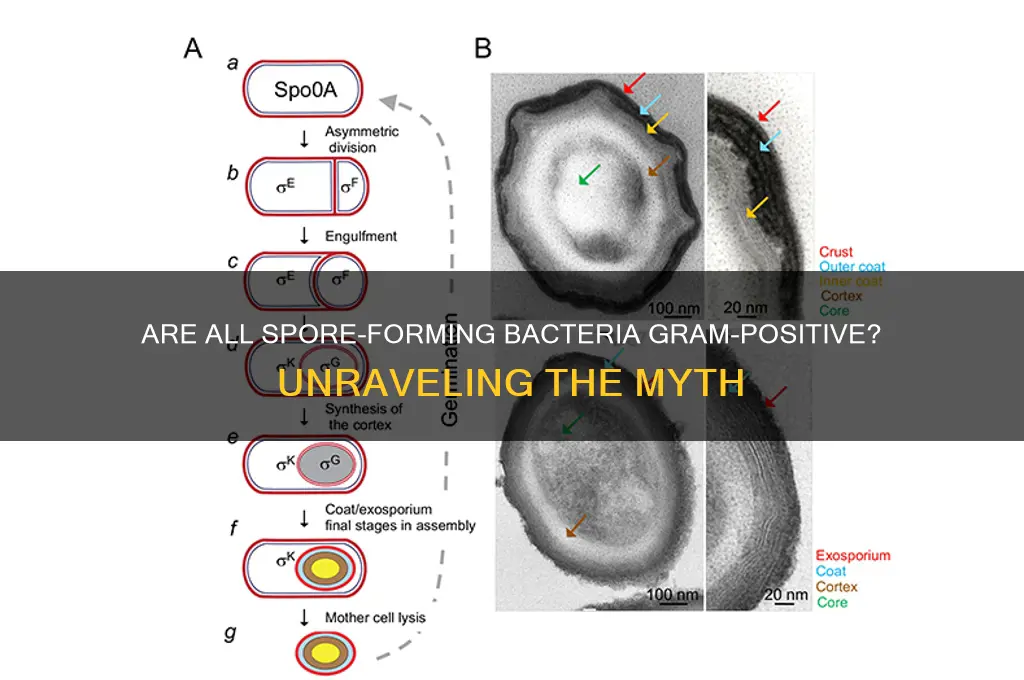

The mechanism of spore formation begins with the activation of a genetic program triggered by nutrient depletion or other stress signals. In *Bacillus subtilis*, a model organism for sporulation studies, this process is regulated by a cascade of sigma factors that control gene expression at different stages. The first morphological change is the formation of an asymmetrically positioned septum, dividing the cell into a larger mother cell and a smaller forespore. The mother cell then engulfs the forespore, creating a double-membrane structure. This engulfment is a critical step, requiring precise coordination of cytoskeletal elements and membrane dynamics.

As sporulation progresses, the forespore undergoes a series of protective modifications. A thick layer of peptidoglycan, known as the cortex, is deposited between the inner and outer spore membranes. Concurrently, the spore coat, composed of multiple layers of proteins, is assembled outside the cortex. This coat acts as a barrier against environmental stressors, including heat, desiccation, and chemicals. In some species, an additional layer called the exosporium is formed, providing further protection and surface properties that aid in spore dispersal.

One of the most remarkable aspects of spore formation is the synthesis of dipicolinic acid (DPA), a calcium-chelating molecule that accumulates in the spore core. DPA plays a crucial role in spore resistance by stabilizing the DNA and proteins in a dehydrated state. The exact mechanism of DPA incorporation remains under investigation, but its presence is a hallmark of mature spores. Interestingly, the level of DPA in spores can vary depending on the species and environmental conditions, with *Bacillus* spores typically containing 10–20% of their dry weight as DPA.

Understanding spore formation mechanisms has practical implications, particularly in food safety, healthcare, and biotechnology. For instance, spores of *Clostridium botulinum* can survive industrial canning processes, necessitating specific thermal treatments (e.g., 121°C for 3 minutes) to ensure food safety. Similarly, spores of *Bacillus anthracis* pose a bioterrorism threat due to their resilience. Conversely, spores of *Bacillus thuringiensis* are harnessed as biopesticides, highlighting the dual nature of this survival strategy. By dissecting the intricacies of sporulation, researchers can develop targeted interventions to control harmful spores while leveraging beneficial ones.

Seeds vs. Spores: Unveiling the Unique Differences in Plant Reproduction

You may want to see also

Clinical Significance of Spore-Forming Bacteria

Spore-forming bacteria, a subset of the microbial world, possess a unique survival mechanism that sets them apart from their non-spore-forming counterparts. Contrary to a common misconception, not all spore-forming bacteria are Gram-positive. While many well-known spore-formers like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* are indeed Gram-positive, there are exceptions. For instance, *Thermotoga* species, which are thermophilic and spore-forming, are Gram-negative. This diversity highlights the complexity of bacterial classification and the need for precise identification in clinical settings.

Clinically, spore-forming bacteria are significant due to their resilience and ability to cause infections under specific conditions. Spores can survive extreme temperatures, desiccation, and exposure to disinfectants, making them challenging to eradicate in healthcare environments. For example, *Clostridioides difficile* (formerly *Clostridium difficile*) is a leading cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and pseudomembranous colitis, particularly in hospitalized patients over 65 years old. The spores of *C. difficile* can persist on surfaces for months, and infection often occurs after disruption of the gut microbiota by broad-spectrum antibiotics like clindamycin or fluoroquinolones. Treatment typically involves discontinuing the offending antibiotic and administering specific antibiotics such as vancomycin (125 mg orally every 6 hours for 10–14 days) or fidaxomicin (200 mg orally every 12 hours for 10 days).

Another clinically significant spore-former is *Bacillus anthracis*, the causative agent of anthrax. While rare, inhalation anthrax is highly lethal, with a mortality rate of up to 75% if untreated. Spores can remain viable in soil for decades, posing a risk in agricultural settings or as a bioterrorism agent. Treatment involves high-dose antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin (500 mg orally every 12 hours) or doxycycline (100 mg orally every 12 hours) for 60 days, often combined with antitoxin therapy. Prophylaxis with these antibiotics is also recommended for exposed individuals.

Understanding the clinical significance of spore-forming bacteria requires a targeted approach to prevention and treatment. In healthcare facilities, stringent infection control measures, including proper hand hygiene and environmental disinfection with sporicidal agents like chlorine bleach (5,000–10,000 ppm), are essential to prevent outbreaks. For patients, early recognition of spore-related infections, such as *C. difficile* colitis or anthrax, is critical. Diagnostic tools like toxin detection assays for *C. difficile* and PCR for *B. anthracis* can expedite treatment. Additionally, judicious use of antibiotics and consideration of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) for recurrent *C. difficile* infections are evidence-based strategies to mitigate the impact of these resilient organisms.

In summary, while not all spore-forming bacteria are Gram-positive, their clinical significance lies in their ability to cause severe, often antibiotic-associated infections. Effective management requires a combination of preventive measures, accurate diagnosis, and tailored treatment regimens. By addressing the unique challenges posed by these bacteria, healthcare providers can reduce morbidity and mortality associated with spore-forming pathogens.

Spore Game Pricing: Cost Details and Purchase Options Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all spore-forming bacteria are gram-positive. While many spore-forming bacteria, such as those in the genus *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, are gram-positive, there are also gram-negative spore-forming bacteria, such as those in the genus *Sporomusa*.

Examples of gram-positive spore-forming bacteria include *Bacillus anthracis* (causes anthrax), *Clostridium botulinum* (produces botulinum toxin), and *Bacillus cereus* (causes food poisoning).

Gram-negative bacteria are less commonly known to form spores compared to gram-positive bacteria. However, a few exceptions exist, such as *Sporomusa* and *Desulfotomaculum*, which are gram-negative and capable of spore formation.

Most spore-forming bacteria are gram-positive because the thick peptidoglycan layer in their cell walls is structurally compatible with the spore formation process. Gram-negative bacteria, with their thinner peptidoglycan layer and additional outer membrane, are less likely to develop spores.