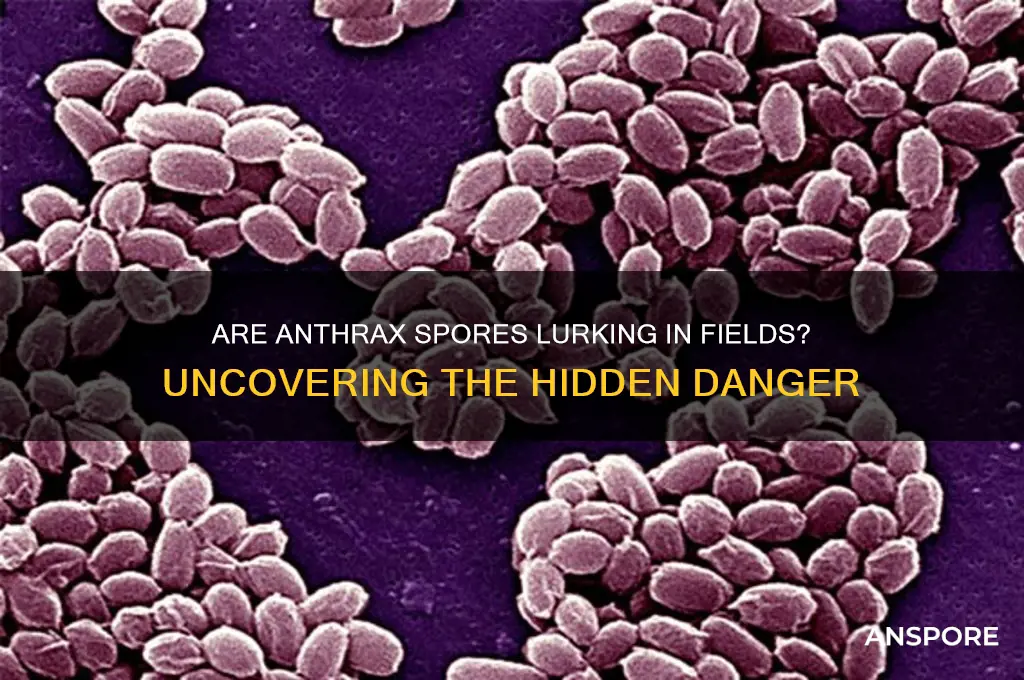

Anthrax spores, primarily caused by the bacterium *Bacillus anthracis*, are known to persist in soil for decades under favorable conditions, particularly in areas where infected animals have died. These spores can contaminate fields, especially in regions with a history of anthrax outbreaks in livestock. While not commonly found in all fields, they pose a risk in endemic areas, particularly for grazing animals and humans who come into contact with contaminated soil. Understanding the presence of anthrax spores in fields is crucial for implementing preventive measures, such as vaccination of livestock and proper disposal of infected carcasses, to mitigate the risk of transmission to both animals and humans.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Presence in Fields | Anthrax spores can be found in soil, particularly in areas where infected animals have died. They are more commonly associated with agricultural regions and can persist in the environment for decades. |

| Geographic Distribution | Spores are more frequently reported in certain regions, such as parts of Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and Southern Europe, where anthrax is endemic in livestock. |

| Survival in Soil | Anthrax spores are highly resilient and can survive in soil for many years, even decades, under favorable conditions (e.g., alkaline soil, high calcium content). |

| Transmission to Humans | Humans can contract anthrax through contact with contaminated soil, especially when spores enter the body through cuts or abrasions, or by inhaling them in dusty environments. |

| Risk Factors | Occupations involving agriculture, animal handling, or working in endemic areas increase the risk of exposure to anthrax spores in fields. |

| Detection Methods | Spores can be detected through soil sampling and laboratory testing, including PCR (polymerase chain reaction) and culture methods. |

| Prevention Measures | Avoiding contact with potentially contaminated soil, wearing protective clothing, and vaccinating livestock in endemic areas can reduce the risk of exposure. |

| Environmental Factors | Spores thrive in alkaline, nutrient-rich soils with high calcium content, which are common in agricultural fields. |

| Public Health Concern | While rare, anthrax outbreaks in fields pose a significant public health risk, particularly in regions with poor healthcare infrastructure. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Common habitats for anthrax spores

Anthrax spores, the dormant form of the bacterium *Bacillus anthracis*, are remarkably resilient and can persist in soil for decades. This longevity makes certain environments, particularly fields, ideal reservoirs for these spores. Agricultural areas where livestock have been infected are prime examples. When animals succumb to anthrax, their carcasses can contaminate the surrounding soil, leaving behind spores that remain viable under favorable conditions. This is why fields with a history of livestock grazing or burial sites of infected animals are often considered high-risk zones.

Understanding the factors that contribute to spore survival is crucial for identifying common habitats. Anthrax spores thrive in alkaline, nutrient-rich soils with a pH between 6.5 and 9.0. They are also more likely to persist in areas with good drainage, as waterlogged conditions can hinder their survival. Fields with these characteristics, especially those located in temperate or tropical regions, are particularly susceptible to spore contamination. For instance, the infamous "anthrax triangle" in Zimbabwe, known for its alkaline soils and history of outbreaks, highlights how environmental factors play a pivotal role in spore distribution.

While fields are a well-documented habitat for anthrax spores, it’s important to distinguish between natural occurrence and human-induced contamination. Agricultural practices such as overgrazing or improper disposal of infected animal remains can inadvertently spread spores across larger areas. In contrast, spores in undisturbed fields may remain localized, posing a risk primarily to wildlife and livestock. Farmers and landowners should be vigilant in areas where anthrax has been historically reported, implementing measures like soil testing and vaccination of animals to mitigate risks.

Comparatively, urban environments are less likely to harbor anthrax spores naturally, but they are not immune to contamination. Spores can be introduced through contaminated soil, animal products, or intentional release, as seen in bioterrorism incidents. However, the focus on fields remains critical due to their direct link to livestock and human exposure. For example, farmers tilling soil in endemic areas may inadvertently aerosolize spores, increasing the risk of inhalation anthrax. This underscores the need for awareness and preventive measures in agricultural settings.

In practical terms, anyone working in or near fields in endemic regions should take precautions. Wearing protective gear, such as masks and gloves, can reduce the risk of spore inhalation or skin contact. Regularly monitoring livestock for signs of anthrax and promptly reporting suspected cases to authorities is essential. Additionally, avoiding the burial of infected animals in fields and instead opting for controlled incineration can prevent long-term soil contamination. By understanding and addressing the specific conditions that favor spore survival, we can minimize the risks associated with anthrax in field environments.

Unlocking Gut Health: Understanding Spore-Based Probiotics and Their Benefits

You may want to see also

Risk factors in agricultural fields

Anthrax spores can persist in soil for decades, making agricultural fields in endemic regions a potential reservoir for infection. This longevity is due to the spore’s resilient structure, which allows it to withstand harsh environmental conditions. Fields with a history of anthrax outbreaks, particularly in areas where livestock have been affected, pose a higher risk. Soil pH, moisture levels, and organic matter content further influence spore survival, with neutral to slightly alkaline soils and moderate moisture favoring persistence. Farmers and workers in these regions must remain vigilant, as disturbance of contaminated soil during plowing or grazing can release spores into the air, increasing exposure risk.

Identifying risk factors in agricultural fields requires a systematic approach. First, assess the field’s history for documented anthrax cases in animals or humans. Second, consider the presence of wild or domestic herbivores, as they are primary vectors for spore transmission. Third, evaluate soil conditions, as spores thrive in well-drained, nutrient-rich soils. Practical steps include testing soil samples for spore presence, especially before tilling or planting. For high-risk areas, avoid grazing livestock until spore levels are confirmed safe. Protective measures, such as wearing masks and gloves during fieldwork, can mitigate inhalation and cutaneous exposure risks.

Comparatively, fields in regions with no history of anthrax pose a lower risk but are not immune. Spores can be introduced through contaminated animal products, such as bones or hides, buried in soil. Additionally, migratory animals or birds may carry spores from endemic areas, depositing them in previously unaffected fields. This highlights the importance of biosecurity measures, such as proper disposal of animal remains and monitoring livestock health. While the risk is lower, complacency can lead to unexpected outbreaks, as seen in sporadic cases in non-endemic regions.

Persuasively, the economic and health implications of anthrax in agricultural fields demand proactive management. An outbreak can lead to livestock deaths, trade restrictions, and human infections, with inhalation anthrax having a fatality rate of up to 75% if untreated. Early detection through soil testing and animal surveillance is cost-effective compared to the financial and emotional toll of an outbreak. Governments and farmers must collaborate to implement risk-based strategies, such as vaccinating livestock in high-risk areas and educating workers on spore exposure risks. By prioritizing prevention, the agricultural sector can safeguard both productivity and public health.

Natural Ways to Eliminate Airborne Mold Spores in Your Home

You may want to see also

Detection methods for spores

Anthrax spores, particularly those of *Bacillus anthracis*, can persist in soil for decades, making their detection in fields a critical concern for public health and agriculture. Identifying these spores requires precise methods that distinguish them from benign bacteria and environmental contaminants. Below are key detection strategies, each with unique advantages and limitations.

Culture-Based Methods: The Traditional Approach

Culturing remains a cornerstone for detecting anthrax spores. Samples from fields are incubated in nutrient-rich media, such as blood agar, under controlled conditions (37°C for 18–24 hours). Colonies of *B. anthracis* appear as large, gray-white, non-hemolytic colonies. Confirmatory tests, including motility checks (anthrax is non-motile) and gamma phage lysis, are essential to rule out false positives. While reliable, this method is time-consuming, taking up to 72 hours, and requires biosafety level 2 (BSL-2) facilities to handle potentially hazardous samples.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): Rapid and Specific

PCR amplifies DNA sequences unique to *B. anthracis*, such as the *pag* gene, enabling detection within hours. Soil samples are pre-treated with agents like lysozyme to break spore coats, followed by DNA extraction and amplification. Real-time PCR variants, such as quantitative PCR (qPCR), quantify spore concentration, aiding risk assessment. However, PCR is sensitive to inhibitors in soil (e.g., humic acids), requiring meticulous sample preparation. False positives can occur if closely related *Bacillus* species are present, emphasizing the need for primer specificity.

Immunological Assays: Speed and Portability

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) and lateral flow devices (LFDs) use antibodies to detect anthrax spore antigens, such as protective antigen (PA). These methods are rapid (<30 minutes) and deployable in the field, making them ideal for initial screening. For instance, the Anthrax Quick Test (AQT) detects PA with 95% sensitivity. However, cross-reactivity with non-pathogenic *Bacillus* species limits specificity, and environmental debris can interfere with antibody binding, necessitating sample filtration.

Spectroscopic Techniques: Non-Invasive Detection

Raman spectroscopy and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) identify spores based on their unique biochemical signatures. These methods are non-destructive and provide results in minutes, making them suitable for large-scale field surveys. For example, Raman spectroscopy detects the calcium dipicolinate marker in anthrax spores with high accuracy. However, these techniques require expensive equipment and trained operators, and their effectiveness diminishes in complex soil matrices.

Biosensors: The Future of Detection

Emerging biosensors integrate biological elements (e.g., antibodies, aptamers) with transducers to detect spores in real-time. For instance, a cantilever-based sensor coated with anti-PA antibodies detects spore binding via nanomechanical changes. These devices offer portability and rapidity but are still in developmental stages, with challenges in sensitivity and environmental robustness. Field validation is critical to ensure reliability in diverse soil conditions.

In conclusion, selecting a detection method depends on context: culture-based methods for definitive identification, PCR for rapid quantification, immunological assays for field screening, spectroscopic techniques for non-invasive analysis, and biosensors for future applications. Each method complements the others, forming a multi-tiered approach to ensure accurate and timely detection of anthrax spores in fields.

Ultimate Sterilization: Processes That Annihilate All Microbial Life, Including Spores

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Prevention strategies for farmers

Anthrax spores can persist in soil for decades, posing a latent threat to livestock and humans in agricultural settings. For farmers, understanding and implementing prevention strategies is crucial to mitigate the risk of anthrax outbreaks. One of the most effective measures is routine soil testing in areas with a history of anthrax cases. While anthrax spores are not commonly found in all fields, regions with alkaline soils and high organic matter content are particularly conducive to spore survival. Testing can identify high-risk zones, allowing farmers to take targeted precautions.

Vaccination of livestock is another cornerstone of prevention. Anthrax vaccines for animals, such as the Sterne strain vaccine, are highly effective and should be administered annually in endemic areas. For cattle, sheep, and goats, a single dose of 1–2 ml subcutaneously provides immunity for at least a year. Farmers should consult veterinarians to develop a vaccination schedule tailored to their herd size and local risk factors. Additionally, isolating and monitoring new or sick animals can prevent the spread of spores within the herd.

Proper disposal of carcasses is critical, as anthrax spores are released during decomposition. Farmers should avoid burying animals in areas prone to flooding, as water can carry spores to new locations. Instead, incineration or deep burial (at least 6 feet) in well-drained soil is recommended. Wearing protective gear, such as gloves and masks, during handling reduces human exposure. Local authorities should be notified immediately to guide disposal and decontamination procedures.

Educating farm workers about anthrax symptoms in both animals and humans is essential for early detection. Livestock may exhibit sudden death, bloody discharges, or swelling, while humans can develop skin ulcers, respiratory distress, or gastrointestinal symptoms. Workers should avoid contact with suspicious carcasses and report findings promptly. Regular training sessions and accessible informational materials can empower workers to act swiftly and safely.

Finally, land management practices can reduce spore proliferation. Avoiding overgrazing and maintaining soil pH below 6.0 can create less favorable conditions for spore survival. Rotating grazing areas and incorporating lime sparingly in alkaline soils can also help. While anthrax spores in fields are not inevitable, proactive measures ensure farmers can protect their livelihoods and public health.

Unveiling the Unique Appearance of Morel Spores: A Visual Guide

You may want to see also

Historical outbreaks linked to fields

Anthrax spores have long persisted in soil, silently lurking in fields and pastures, ready to resurface under the right conditions. Historical outbreaks linked to these environments highlight the bacterium’s resilience and the recurring risks it poses to both animals and humans. One of the most notable examples is the 1979 anthrax outbreak in the Sverdlovsk region of the Soviet Union, where spores released from a military facility contaminated nearby fields. Livestock grazing in these areas became infected, and the disease eventually spread to humans, resulting in 68 confirmed cases and 64 deaths. This incident underscores how anthrax spores, once introduced into soil, can remain viable for decades, posing a latent threat to agricultural communities.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, anthrax outbreaks in European fields were so common that the disease earned the name "woolsorters' disease." Workers handling contaminated animal hides or wool from infected livestock contracted the disease through cuts or inhalation. These outbreaks were not limited to humans; entire herds of cattle, sheep, and goats perished in fields across France, Germany, and England. The spores entered the soil through the remains of these animals, creating reservoirs of infection that persisted for years. Farmers often reported recurring outbreaks in the same fields, unaware that the soil itself was the source of the problem. This historical pattern emphasizes the importance of proper disposal of infected animal carcasses to prevent soil contamination.

A more recent example is the 2000–2001 anthrax outbreak in Scotland, where spores in the soil of a former military testing site caused infections in livestock. The site, used for anthrax experiments in the 1940s, had been converted to farmland, but the spores remained dormant until disturbed by agricultural activities. Cattle grazing in the area became infected, and one farmer contracted cutaneous anthrax after handling an infected animal. This case illustrates how historical land use can leave a dangerous legacy, requiring thorough soil testing and remediation before repurposing such areas for agriculture.

Preventing anthrax outbreaks linked to fields requires a multi-pronged approach. First, identify high-risk areas by researching historical land use and conducting soil tests for spore presence. Second, implement biosecurity measures, such as fencing off contaminated fields and avoiding grazing in known hotspots. Third, vaccinate livestock in endemic regions, as vaccines have proven effective in reducing animal infections. For humans, protective gear and hygiene practices are essential when handling animals or working in potentially contaminated fields. Finally, educate farmers and communities about the risks and symptoms of anthrax to ensure early detection and treatment. By learning from historical outbreaks, we can mitigate the threat of anthrax spores in fields and protect both agricultural livelihoods and public health.

Optimal Timing for Planting Morel Spores: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Anthrax spores can be found in fields, particularly in areas where herbivorous animals have been infected. The spores can persist in soil for decades, posing a risk to livestock and, in rare cases, humans.

Anthrax spores are released into the environment when infected animals die, and their carcasses decompose. The spores contaminate the surrounding soil, where they can remain dormant until ingested by susceptible animals or disturbed by human activity.

While rare, humans can contract anthrax from fields with contaminated soil, especially if they come into contact with infected animal products or inhale spores during activities like farming or digging. Proper precautions, such as wearing protective gear, can reduce risk.

Anthrax spores in fields can be detected through soil testing and monitoring livestock health. Management strategies include vaccinating animals, proper disposal of infected carcasses, and avoiding activities that disturb contaminated soil.