Spores are reproductive structures produced by various organisms, including plants, fungi, and some bacteria, and their ploidy level can vary depending on the species and life cycle stage. While many spores, such as those in ferns and mosses, are indeed haploid, formed through meiosis and containing a single set of chromosomes, others, like the zygospores in certain fungi, are diploid, resulting from the fusion of two haploid gametes. This diversity in spore ploidy highlights the complexity of reproductive strategies across different organisms, making the question Are all spores diploid? a nuanced one that requires consideration of the specific organism and its life cycle.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Are all spores diploid? | No, not all spores are diploid. |

| Types of Spores | 1. Diploid Spores: Found in some fungi and plants (e.g., zygospores in fungi, spores in certain algae). 2. Haploid Spores: Common in plants (e.g., pollen grains, spores in ferns, mosses) and some fungi (e.g., ascospores, basidiospores). |

| Ploidy Definition | Diploid (2n): Contains two sets of chromosomes. Haploid (n): Contains one set of chromosomes. |

| Life Cycle Context | In alternation of generations (e.g., plants, some algae, fungi), spores are often haploid, produced by meiosis and developing into gametophytes. Diploid spores are less common and typically result from specific reproductive processes. |

| Examples of Diploid Spores | Zygospores in fungi, certain algal spores. |

| Examples of Haploid Spores | Fern spores, moss spores, pollen grains, ascospores, basidiospores. |

| Significance | Ploidy of spores depends on the organism's life cycle and reproductive strategy. Haploid spores are more widespread in nature. |

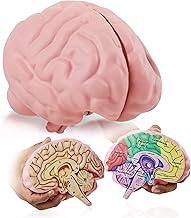

Explore related products

$9.99 $10.99

What You'll Learn

- Spores in Fungi: Most fungal spores are haploid, produced via meiosis for genetic diversity

- Plant Spores: Alternation of generations; spores in plants are typically haploid

- Bacterial Spores: Endospores are dormant, not reproductive, and retain diploid status

- Zygospores in Fungi: Formed by fusion of gametangia, zygospores are diploid

- Spores vs. Gametes: Spores can be diploid or haploid; gametes are always haploid

Spores in Fungi: Most fungal spores are haploid, produced via meiosis for genetic diversity

Fungal spores are predominantly haploid, a fact that distinguishes them from many other reproductive structures in the biological world. This haploid nature is a direct result of their production through meiosis, a process that reduces the chromosome number by half, ensuring genetic diversity. Unlike diploid spores, which carry two sets of chromosomes, haploid spores contain only one set, making them lighter, more resilient, and better suited for dispersal. This adaptation is crucial for fungi, which often rely on wind, water, or animals to spread their spores across diverse environments.

Consider the life cycle of *Aspergillus*, a common mold genus. After the fungus matures, it undergoes meiosis to produce haploid spores called conidia. These spores are not only lightweight but also highly resistant to harsh conditions, such as extreme temperatures and desiccation. This resilience allows them to survive until they land in a suitable environment, where they germinate and grow into new fungal colonies. The haploid nature of these spores ensures that each one carries a unique genetic makeup, increasing the species’ adaptability to changing environments.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the haploid nature of fungal spores is essential for fields like agriculture and medicine. For instance, farmers combating fungal pathogens like *Botrytis cinerea* (gray mold) must recognize that these haploid spores can rapidly evolve resistance to fungicides. Rotating fungicides with different modes of action and integrating cultural practices, such as reducing humidity and improving air circulation, can mitigate this risk. Similarly, in medical mycology, knowing that fungal spores are haploid helps explain why infections like aspergillosis can be so challenging to treat, as the spores’ genetic diversity allows them to evade host immune responses and antifungal drugs.

Comparatively, diploid spores, such as those found in some algae and plants, serve different ecological roles. While diploid spores are often larger and more nutrient-rich, they are less suited for long-distance dispersal and harsh conditions. Fungi, however, prioritize quantity and resilience over size, producing vast numbers of haploid spores to maximize their chances of survival and colonization. This strategy reflects their evolutionary success, as fungi are among the most widespread and diverse organisms on Earth.

In conclusion, the haploid nature of most fungal spores is a key to their survival and proliferation. Produced via meiosis, these spores embody genetic diversity, enabling fungi to adapt to diverse and often hostile environments. Whether in the lab, the field, or the clinic, recognizing this fundamental characteristic of fungal spores provides valuable insights into their biology and informs strategies for managing fungal growth and disease.

Spore Syringe Shelf Life: Fridge Storage Duration Explained

You may want to see also

Plant Spores: Alternation of generations; spores in plants are typically haploid

Spores in the plant kingdom defy the assumption that all spores are diploid. Unlike fungal spores, which are often diploid, plant spores are predominantly haploid, a critical feature of their life cycle known as alternation of generations. This process involves a fascinating switch between two distinct phases: a haploid gametophyte and a diploid sporophyte. Understanding this alternation is key to grasping the unique reproductive strategy of plants.

For example, consider the life cycle of a fern. The familiar fern fronds we see are the sporophyte generation, which produce haploid spores via meiosis. These spores germinate into tiny, heart-shaped gametophytes (prothalli) that are often overlooked but crucial. The prothalli produce gametes (sperm and eggs), which, upon fertilization, develop into a new sporophyte, completing the cycle. This alternation ensures genetic diversity and adaptability, hallmarks of plant survival strategies.

The haploid nature of plant spores is not merely a biological curiosity but a strategic evolutionary adaptation. Haploid organisms have a single set of chromosomes, making them more susceptible to genetic mutations. While this might seem like a disadvantage, it actually fosters rapid evolution. Mutations in haploid spores can quickly become apparent in the next generation, allowing plants to adapt swiftly to changing environments. This is particularly advantageous in diverse ecosystems where conditions can fluctuate dramatically.

To illustrate, let’s examine mosses, another group of plants with a prominent haploid phase. The moss gametophyte is the dominant, long-lived phase, while the sporophyte is dependent on it. This contrasts with ferns and seed plants, where the sporophyte dominates. Such variations in the alternation of generations highlight the flexibility of this reproductive strategy across plant lineages. For gardeners or botanists, recognizing these phases can aid in propagation techniques, such as cultivating mosses from spores or encouraging fern growth through optimal gametophyte conditions.

In practical terms, understanding the haploid nature of plant spores can inform conservation efforts and agricultural practices. For instance, in reforestation projects, knowing the spore dispersal mechanisms of ferns or lycophytes can enhance success rates. Similarly, in horticulture, manipulating environmental conditions to favor gametophyte growth can improve the cultivation of certain plant species. By appreciating the alternation of generations, we gain insights into the resilience and diversity of plant life, underscoring the importance of preserving these intricate life cycles.

Understanding Spore Prints: A Beginner's Guide to Mushroom Identification

You may want to see also

Bacterial Spores: Endospores are dormant, not reproductive, and retain diploid status

Bacterial endospores defy the reproductive role typically associated with spores in fungi and plants. Unlike their eukaryotic counterparts, which often serve as agents of dispersal and reproduction, endospores are survival structures. Formed by certain bacteria like *Clostridium* and *Bacillus*, they are a last-ditch effort to endure harsh conditions such as extreme heat, desiccation, or chemical exposure. This distinction is crucial: endospores are not reproductive units but rather dormant forms that retain the genetic material of the parent cell, typically in a diploid state, until conditions improve.

The diploid status of bacterial endospores is a direct result of their formation process. During sporulation, the bacterial cell replicates its chromosome but does not divide immediately. Instead, one copy of the DNA is enclosed within a protective spore structure, while the other remains in the vegetative cell, which eventually lyses. This ensures the endospore retains the full genetic complement of the parent, maintaining its diploid nature. Unlike haploid fungal spores, which are produced through meiosis and are genetically distinct, endospores are clones of the original cell, preserving its genetic integrity.

One practical implication of this diploid retention is the endospore’s ability to revive and resume growth rapidly once conditions become favorable. For instance, in food preservation, endospores of *Clostridium botulinum* can survive boiling temperatures (100°C) for hours, only to germinate and cause botulism if not properly sterilized. To neutralize such risks, industries employ autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes, ensuring complete destruction of endospores. This highlights the importance of understanding their dormant, resilient nature, which is underpinned by their diploid genetic stability.

Comparatively, while fungal spores like those of *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium* are haploid and reproductive, bacterial endospores are a testament to survival rather than propagation. Their diploid status is not a prelude to genetic diversity but a safeguard for genetic continuity. This distinction is vital in fields like microbiology and biotechnology, where controlling spore germination is critical. For example, in soil remediation, endospores of *Bacillus subtilis* can remain dormant for decades, only to revive and degrade pollutants when conditions permit, showcasing their unique ecological role.

In conclusion, bacterial endospores challenge the assumption that all spores are reproductive or haploid. Their diploid status, coupled with their dormant nature, underscores their role as survival mechanisms rather than agents of dispersal. Understanding this unique characteristic is essential for applications ranging from food safety to environmental biotechnology, where the resilience of endospores demands specific strategies to either harness or neutralize their capabilities.

Understanding Spore-Forming Bacteria: Survival Mechanisms and Health Implications

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Zygospores in Fungi: Formed by fusion of gametangia, zygospores are diploid

Zygospores, a distinctive feature of certain fungi, are the product of a fascinating reproductive process. Unlike many other spores, zygospores are formed through the fusion of two gametangia, specialized structures that house haploid gametes. This union results in a diploid zygospore, a critical stage in the fungal life cycle. The diploid nature of zygospores is a key point of interest when considering the broader question of whether all spores are diploid. In the case of zygospores, the answer is unequivocally yes, but this is not a universal rule for all fungal spores.

To understand the significance of zygospores, consider the steps involved in their formation. First, compatible fungal hyphae grow toward each other, often in response to chemical signals. Next, the tips of these hyphae differentiate into gametangia, which then fuse to form a zygote. This zygote develops into a thick-walled zygospore, capable of withstanding harsh environmental conditions. The diploid state of the zygospore is essential for genetic recombination, allowing fungi to adapt and evolve. For example, in the phylum Zygomycota, this process is crucial for species survival, particularly in unpredictable environments where genetic diversity can provide a competitive edge.

From a practical standpoint, understanding zygospores can aid in fungal identification and control. For instance, in agricultural settings, recognizing the presence of zygospores in soil samples can indicate the type of fungi present and their potential impact on crops. Laboratory techniques, such as microscopy and DNA analysis, can be employed to identify zygospores and assess their diploid nature. This knowledge is invaluable for developing targeted fungicides or management strategies. For hobbyists or students, observing zygospore formation under a microscope can be a rewarding educational experience, requiring minimal equipment—a basic light microscope, fungal cultures, and proper staining techniques.

Comparatively, zygospores stand apart from other fungal spores like conidia or basidiospores, which are typically haploid. This distinction highlights the diversity of fungal reproductive strategies. While conidia are asexual spores produced by mitosis, zygospores result from sexual reproduction, ensuring genetic variation. This difference is not just academic; it has practical implications for industries like biotechnology, where understanding spore types can influence the selection of fungi for processes like fermentation or enzyme production. For example, diploid zygospores might be favored in genetic engineering projects aimed at creating stable, hybrid fungal strains.

In conclusion, zygospores in fungi exemplify a unique reproductive mechanism where the fusion of gametangia results in a diploid spore. This process is not only a biological curiosity but also a practical consideration in fields ranging from agriculture to biotechnology. By focusing on the specifics of zygospore formation and function, we gain insights into fungal biology that can be applied in real-world scenarios. Whether for scientific research, educational purposes, or industrial applications, the study of zygospores offers a window into the complex and adaptable world of fungi.

Is Spore Available on Xbox? Exploring Compatibility and Gaming Options

You may want to see also

Spores vs. Gametes: Spores can be diploid or haploid; gametes are always haploid

Spores and gametes are both reproductive structures, yet they differ fundamentally in their ploidy and function. While gametes are universally haploid—containing a single set of chromosomes and serving as the basis for sexual reproduction—spores exhibit greater variability. Depending on the organism and its life cycle, spores can be either diploid (carrying two sets of chromosomes) or haploid. This distinction is crucial for understanding the reproductive strategies of plants, fungi, and certain protists.

Consider the life cycle of ferns, a classic example of alternation of generations. Here, the sporophyte (diploid) phase produces haploid spores via meiosis. These spores germinate into gametophytes, which are haploid and produce gametes. In contrast, fungi like mushrooms often release diploid spores, which directly grow into new individuals without a haploid phase. This diversity in spore ploidy highlights the adaptability of spores as survival and dispersal units, whereas gametes remain strictly haploid to ensure genetic recombination during fertilization.

To illustrate further, examine the role of spores in plant reproduction. In mosses, the dominant gametophyte phase produces haploid spores, while in seed plants like angiosperms, the sporophyte phase dominates, and pollen grains (male gametophytes) are reduced to just a few haploid cells. Conversely, gametes—whether sperm or egg—are always haploid, ensuring that fertilization restores the diploid state. This consistency in gamete ploidy is essential for maintaining genetic stability across generations.

Practical implications of these differences arise in agriculture and conservation. For instance, understanding spore ploidy helps in breeding programs for crops like potatoes, where diploid spores can simplify genetic manipulation. In contrast, the haploid nature of gametes is leveraged in techniques like in vitro fertilization, where precise control over ploidy is critical. Recognizing these distinctions allows scientists and practitioners to optimize reproductive strategies for specific goals.

In summary, while gametes are uniformly haploid to facilitate sexual reproduction, spores exhibit flexibility in ploidy, reflecting their diverse roles in survival and dispersal. This contrast underscores the complexity of reproductive biology and its practical applications. Whether in a laboratory or a forest, grasping these nuances empowers us to harness the potential of both spores and gametes effectively.

Optimal Timing for Planting Morel Spores: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all spores are diploid. Spores can be either haploid or diploid, depending on the organism and its life cycle.

The ploidy of a spore is determined by the life cycle stage of the organism. In organisms with alternation of generations, spores produced by the diploid sporophyte are typically haploid, while spores produced by the haploid gametophyte are diploid in some cases.

No, fungal spores are usually haploid. They are produced by the diploid stage (sporophyte) through meiosis, resulting in haploid spores that develop into the gametophyte stage.

No, in plants with alternation of generations, spores are typically haploid. They are produced by the diploid sporophyte and develop into the haploid gametophyte, which then produces gametes for sexual reproduction.