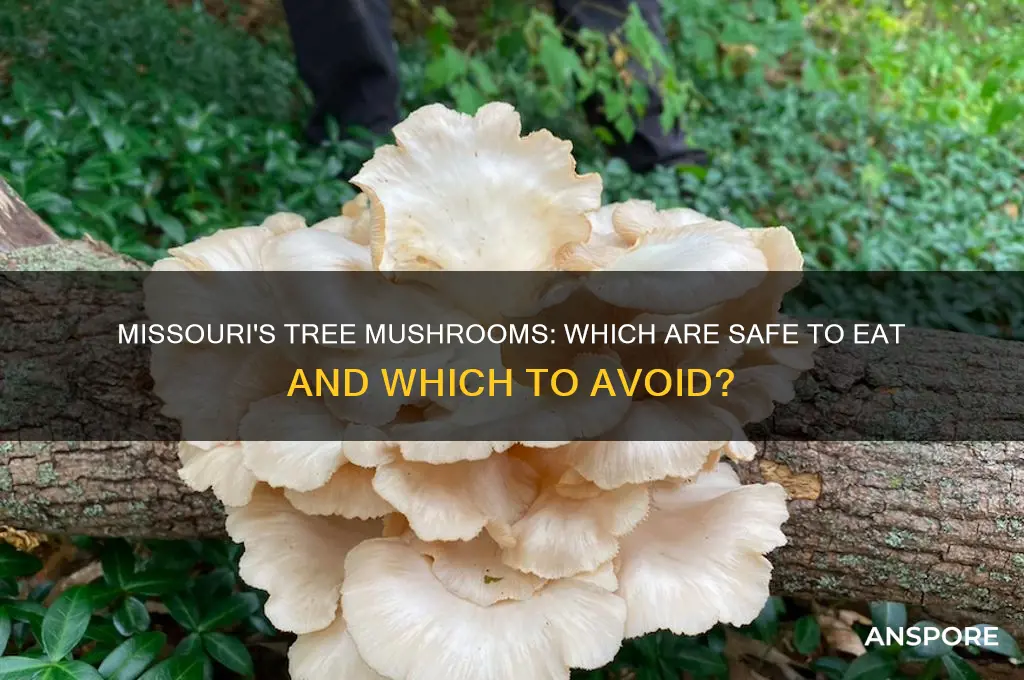

Missouri is home to a diverse array of tree mushrooms, which can be both fascinating and potentially dangerous for foragers. While some tree mushrooms, like certain species of oyster mushrooms, are edible and highly prized, others can be toxic or even deadly if consumed. Identifying these fungi accurately is crucial, as many species resemble one another, and misidentification can lead to serious health risks. Factors such as the tree species the mushroom grows on, its physical characteristics, and the time of year can all influence edibility. Therefore, it is essential for anyone interested in foraging tree mushrooms in Missouri to educate themselves thoroughly or consult with experienced mycologists to ensure safe and informed harvesting practices.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| All Tree Mushrooms Edible in Missouri | Not all tree mushrooms in Missouri are edible. Some are toxic and can cause severe illness or death. |

| Common Edible Tree Mushrooms | Chicken of the Woods (Laetiporus sulphureus), Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus), Lion's Mane (Hericium erinaceus) |

| Common Toxic Tree Mushrooms | Jack-O-Lantern (Omphalotus olearius), False Chanterelle (Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca), Deadly Galerina (Galerina marginata) |

| Identification Importance | Proper identification is crucial before consuming any wild mushroom. Consult expert guides, field manuals, or mycologists. |

| Habitat | Tree mushrooms grow on living or dead trees, stumps, and woody debris. |

| Season | Most tree mushrooms in Missouri fruit in late summer to fall, but some species may appear earlier or later. |

| Legal Considerations | Foraging on private land requires permission, and some public lands may have restrictions on mushroom harvesting. |

| Safety Tips | Never eat a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identification. Cook all wild mushrooms thoroughly before consumption. |

| Resources | Missouri Department of Conservation, local mycological societies, and reputable field guides. |

Explore related products

$7.62 $14.95

What You'll Learn

Common edible tree mushrooms in Missouri

Not all tree mushrooms in Missouri are edible, and misidentification can lead to severe illness or even death. However, several species are not only safe but also prized for their culinary value. Among these, the Chicken of the Woods (*Laetiporus sulphureus*) stands out with its vibrant orange-yellow fan-like clusters that grow on hardwood trees like oak. Its texture and flavor resemble cooked chicken, making it a favorite in stir-fries and soups. Harvest young, tender specimens, and always cook thoroughly to avoid digestive discomfort.

Another notable edible is the Lion’s Mane (*Hericium erinaceus*), a shaggy, white mushroom that grows on deciduous trees, particularly beech and maple. Its unique appearance and crab-like flavor make it a gourmet choice. Rich in neuroprotective compounds, it’s often consumed in teas or supplements, but its culinary versatility shines in dishes like crab cakes or sautéed with butter and garlic. Foraging tip: look for it in late summer to early fall, and ensure it’s free of insects before cooking.

For those seeking a more earthy flavor, the Oyster Mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) is a common find on dead or dying hardwoods. Its delicate, fan-shaped caps are best when young and can be used in almost any recipe requiring mushrooms. A practical tip: these mushrooms are excellent for beginners due to their distinct appearance and lack of dangerous look-alikes. However, always avoid specimens growing on conifers, as they may be a toxic species.

While these mushrooms are edible, proper identification is critical. For instance, the Sulphur Shelf (another name for Chicken of the Woods) can be confused with the toxic *Stereum* species, which lacks gills and has a tougher texture. Always cross-reference with multiple field guides or consult an expert. Additionally, avoid harvesting near roadsides or industrial areas due to potential contamination. With caution and knowledge, Missouri’s tree mushrooms can be a rewarding addition to your foraging repertoire.

Are Chicken of the Woods Mushrooms Edible? A Tasty Guide

You may want to see also

Toxic tree mushrooms to avoid in Missouri

Not all tree mushrooms in Missouri are safe to eat. While some, like the lion's mane and chicken of the woods, are prized by foragers, others can cause severe illness or even be fatal. Identifying toxic species requires careful observation and knowledge of key characteristics.

One of the most dangerous tree mushrooms in Missouri is the deadly galerina (Galerina marginata). Often found on decaying wood, this small brown mushroom resembles edible species like the honey mushroom. However, it contains amatoxins, the same toxins found in the infamous death cap mushroom. Ingesting just one can cause severe liver and kidney damage, and symptoms may not appear for 6-24 hours, making it especially treacherous.

Another toxic tree-dwelling fungus to avoid is the sulfur shelf or "chicken of the woods" imposter, Laetiporus conifericola. While the true chicken of the woods (Laetiporus sulphureus) is edible and grows on hardwoods, its conifer-loving cousin can cause gastrointestinal distress in some individuals. This highlights the importance of not only identifying the mushroom but also noting the type of tree it's growing on.

Foraging for mushrooms should always be approached with caution. Never consume a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identification. Carry a reliable field guide specific to Missouri fungi, and consider joining a local mycological society for guidance. Remember, when in doubt, throw it out. The consequences of misidentification can be severe.

Are Lobster Mushrooms Edible? A Guide to Safe Foraging and Cooking

You may want to see also

Identifying safe vs. poisonous tree mushrooms

Not all tree mushrooms in Missouri are safe to eat, and misidentification can lead to severe illness or even death. The key to distinguishing edible species from their toxic counterparts lies in meticulous observation and knowledge of specific characteristics. For instance, the Lion’s Mane mushroom (*Hericium erinaceus*) is a prized edible variety found on hardwood trees, recognizable by its cascading, icicle-like spines. In contrast, the poisonous False Morel (*Gyromitra esculenta*) often grows at the base of trees and resembles a wrinkled brain, containing a toxin called gyromitrin that can cause gastrointestinal distress and, in severe cases, organ failure. Always cross-reference multiple field guides or consult an expert before consuming any wild mushroom.

Color and texture are deceptive identifiers, as both edible and poisonous mushrooms can share similar hues or surfaces. For example, the edible Oyster Mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) has a smooth, fan-like cap and grows in clusters on decaying wood, while the toxic Jack-O-Lantern (*Omphalotus olearius*) mimics its appearance but emits a faint glow in the dark and causes severe cramps. A more reliable method is to examine the spore print—a technique where the mushroom’s cap is placed gills-down on paper overnight to reveal spore color. Edible species like the Chicken of the Woods (*Laetiporus sulphureus*) produce white spores, whereas the toxic Sulphur Tuft (*Hypholoma fasciculare*) releases green-brown spores. This simple test can eliminate many dangerous look-alikes.

Habitat and tree association provide additional clues but should not be the sole basis for identification. Edible mushrooms like the Chaga (*Inonotus obliquus*), a black, charcoal-like growth found on birch trees, have no poisonous doppelgängers, but their unique appearance limits confusion. Conversely, the toxic Velvet Foot (*Flammulina velutipes*) grows on hardwood stumps and resembles the edible Winter Mushroom (*Flammulina populicola*), differing only in spore size and gill attachment. Always note the type of tree and decay stage of the wood, as certain mushrooms are exclusive to specific hosts. For instance, the edible Honey Mushroom (*Armillaria mellea*) prefers oaks and beeches, while its toxic cousin, the Deadly Galerina (*Galerina marginata*), often grows on conifers.

When in doubt, apply the "if you’re not sure, don’t eat it" rule. Even experienced foragers carry field guides or use apps like iNaturalist for real-time identification. Avoid folklore tests like the "silver spoon test" or "animal consumption test," as they are unreliable. Instead, focus on scientific methods: spore prints, gill attachment, bruising reactions, and microscopic spore examination. For beginners, start with easily identifiable species like the Lion’s Mane or Oyster Mushroom, and always cook wild mushrooms thoroughly to break down potential toxins. Remember, no single trait guarantees edibility—only a combination of characteristics can confirm safety.

Can You Eat All Gills-Free Mushrooms? Edibility Myths Debunked

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Seasonal availability of edible tree mushrooms

In Missouri, the seasonal availability of edible tree mushrooms is a fascinating interplay of climate, ecology, and timing. Spring and fall emerge as the prime foraging seasons, with temperature and moisture levels dictating the fruiting cycles of species like chicken of the woods (*Laetiporus sulphureus*) and oyster mushrooms (*Pleurotus ostreatus*). These mushrooms thrive on decaying hardwoods, with spring flushes often appearing after the first warm rains and fall harvests coinciding with cooler, damp conditions. Understanding these patterns is crucial for foragers, as it maximizes yield and ensures the mushrooms are at their most flavorful and nutritious.

Foraging in spring offers a unique advantage: the mushrooms are younger, firmer, and less likely to be infested with insects. Chicken of the woods, for instance, is best harvested when its brackets are bright orange and pliable, typically in late April to early June. Fall, on the other hand, brings a second wave of growth, particularly for oyster mushrooms, which flourish on fallen trees and stumps from September through November. However, foragers must act swiftly, as frost can quickly degrade their quality. A practical tip: carry a field guide or use a mushroom identification app to confirm species, as look-alikes like the toxic *Ganoderma* species can be misleading.

The seasonal availability also influences culinary applications. Spring-harvested mushrooms tend to have a milder, more delicate flavor, making them ideal for sautéing or grilling. Fall mushrooms, richer and earthier, are perfect for hearty soups, stews, or drying for winter use. Preservation methods like dehydration or freezing can extend their shelf life, but always ensure mushrooms are properly identified and cleaned before storage. A cautionary note: never consume mushrooms raw, as many edible species contain compounds that require cooking to neutralize.

Comparing Missouri’s mushroom seasons to those in neighboring states highlights regional variations. While Illinois and Arkansas share similar species, their slightly warmer climates may shift peak foraging times by a week or two. Missouri’s unique mix of hardwood forests and temperate climate creates a distinct window for certain species, such as the lion’s mane (*Hericium erinaceus*), which prefers cooler fall temperatures. Foraging ethically is equally important—always leave some mushrooms behind to ensure spore dispersal and future growth.

In conclusion, mastering the seasonal availability of edible tree mushrooms in Missouri requires a blend of knowledge, timing, and respect for nature. Spring and fall are the golden seasons, each offering distinct opportunities for harvest and culinary exploration. By aligning foraging efforts with ecological rhythms and employing proper identification and preservation techniques, enthusiasts can safely enjoy the bounty of Missouri’s forests year after year.

Are Angel Wings Mushrooms Edible? A Comprehensive Guide to Safety

You may want to see also

Legal foraging guidelines for tree mushrooms in Missouri

In Missouri, foraging for tree mushrooms is subject to specific legal guidelines that ensure sustainability and compliance with state regulations. Unlike some states with strict harvesting laws, Missouri does not require permits for personal mushroom foraging on public lands, but there are important rules to follow. For instance, foragers must avoid damaging trees or the ecosystem while collecting mushrooms, as this can lead to fines or penalties. Understanding these guidelines is crucial for anyone interested in safely and legally harvesting tree mushrooms in the state.

One key aspect of legal foraging in Missouri is the distinction between public and private lands. On public lands, such as state parks or forests, foragers are generally allowed to collect mushrooms for personal use, but commercial harvesting is often prohibited. Private lands, however, require explicit permission from the landowner before any foraging can take place. Trespassing to collect mushrooms can result in legal consequences, so always verify land ownership and obtain written consent when necessary. This simple step ensures your foraging activities remain within the bounds of the law.

Another critical guideline is the quantity limit for mushroom harvesting. While Missouri does not impose strict weight limits for personal use, foragers are expected to practice moderation. Overharvesting can deplete mushroom populations and disrupt local ecosystems. A practical tip is to collect only what you need and leave behind immature mushrooms to allow them to spore and regenerate. This sustainable approach aligns with ethical foraging practices and helps preserve Missouri’s natural resources for future generations.

Foraging for tree mushrooms in Missouri also requires awareness of protected species. Some mushrooms, such as certain morel varieties, are not legally protected but are highly valued and should be harvested responsibly. However, it’s essential to avoid endangered or rare species, as collecting them can result in fines or other penalties. Familiarize yourself with local mushroom guides or consult with mycological experts to identify species that should be left undisturbed. This knowledge ensures your foraging activities are both legal and environmentally conscious.

Lastly, foragers should be mindful of seasonal restrictions and habitat preservation. In Missouri, mushroom season typically peaks in spring and fall, but specific areas may have temporary closures to protect sensitive ecosystems. Always check with local authorities or park rangers for any current restrictions before heading out. Additionally, avoid using tools that damage trees or the forest floor, such as knives or shovels, when harvesting tree mushrooms. Instead, gently twist or cut mushrooms at the base to minimize impact. By adhering to these guidelines, you can enjoy the rewards of foraging while respecting Missouri’s natural environment.

Can You Eat Puffball Mushrooms? A Guide to Safe Consumption

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all tree mushrooms in Missouri are edible. Some are toxic or poisonous, and consuming them can cause severe illness or even be fatal. Always identify mushrooms accurately before consuming them.

Identifying edible tree mushrooms requires knowledge of specific characteristics like color, shape, gills, and spore print. It’s best to consult a field guide, join a mycological society, or seek expert advice, as some toxic mushrooms closely resemble edible ones.

Common edible tree mushrooms in Missouri include the Oyster Mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), Lion’s Mane (*Hericium erinaceus*), and Chicken of the Woods (*Laetiporus sulphureus*). However, proper identification is crucial to avoid confusion with toxic look-alikes.

If you’re unsure, do not eat the mushroom. Take detailed photos, note its characteristics, and consult a local mycologist or mushroom expert. Never rely on folklore or unverified methods to determine edibility.