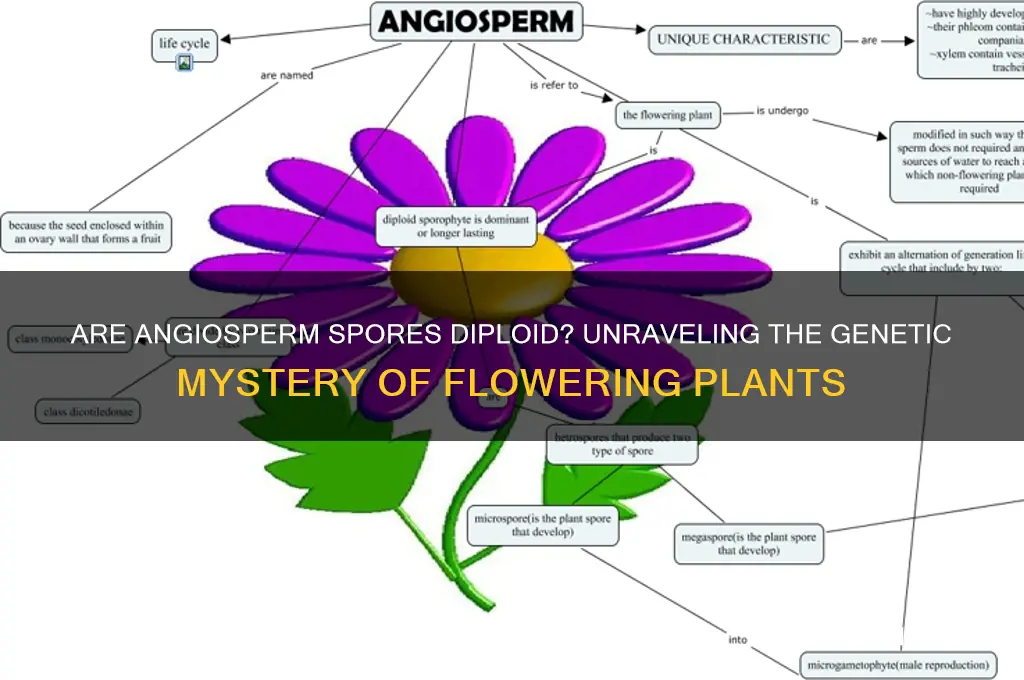

Angiosperms, commonly known as flowering plants, are a diverse group of plants characterized by their production of flowers and seeds enclosed in fruits. Unlike ferns and fungi, which reproduce via spores, angiosperms primarily reproduce through seeds. The life cycle of angiosperms involves alternation of generations, with a dominant sporophyte phase (the plant we see) and a reduced gametophyte phase. In this cycle, spores are produced during the sporophyte phase through meiosis, resulting in haploid spores. However, the question of whether angiosperm spores are diploid arises from a misunderstanding, as spores in angiosperms are indeed haploid. These haploid spores develop into gametophytes, which then produce gametes for sexual reproduction. Thus, while angiosperms do produce spores, they are not diploid; instead, they are haploid, aligning with the fundamental principles of their reproductive biology.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Ploidy of Spores in Angiosperms | Haploid (n) |

| Life Cycle Stage | Spores are produced during the alternation of generations in the plant life cycle. |

| Type of Spores | Microspores (male) and megaspores (female) |

| Development | Microspores develop into pollen grains; megaspores develop into the female gametophyte (embryo sac). |

| Fertilization | After fertilization, the zygote (diploid, 2n) develops into the embryo of the seed. |

| Diploid Stage | The sporophyte generation (e.g., the flowering plant) is diploid (2n). |

| Haploid Stage | The gametophyte generation (e.g., pollen and embryo sac) is haploid (n). |

| Significance | Angiosperms follow a haploid-dominant gametophyte phase, but the sporophyte (diploid) is the dominant and visible stage. |

Explore related products

$21.13 $28

What You'll Learn

- Spore Formation in Angiosperms: Angiosperms produce spores through meiosis, resulting in haploid spores, not diploid

- Life Cycle Stages: Alternation of generations includes diploid sporophyte and haploid gametophyte phases

- Pollen and Embryo Sac: Pollen grains and embryo sacs are haploid, developing from spores

- Double Fertilization: Unique process in angiosperms, involving diploid endosperm and embryo formation

- Sporophyte Dominance: Diploid sporophyte phase is dominant in angiosperms, unlike ferns or mosses

Spore Formation in Angiosperms: Angiosperms produce spores through meiosis, resulting in haploid spores, not diploid

Angiosperms, commonly known as flowering plants, are the most diverse group of land plants, yet their spore formation process is often misunderstood. Unlike ferns or mosses, which produce diploid spores, angiosperms generate haploid spores through meiosis. This fundamental difference is rooted in their life cycle, which alternates between a diploid sporophyte and a haploid gametophyte phase. Meiosis, a type of cell division, reduces the chromosome number by half, ensuring the spores are haploid. These spores then develop into male (pollen) and female (embryo sac) gametophytes, which ultimately produce gametes for sexual reproduction.

To understand this process, consider the steps involved in spore formation. First, within the flower’s anthers and ovules, specialized cells called sporocytes undergo meiosis. This division results in four haploid spores per sporocyte. In the male reproductive system, these spores develop into pollen grains, each containing a generative cell and a tube cell. In the female system, one of the spores enlarges to form the embryo sac, housing the egg cell and other accessory cells. This precise mechanism ensures genetic diversity while maintaining the haploid-diploid alternation characteristic of angiosperms.

A common misconception is that angiosperm spores are diploid, akin to those of non-seed plants. However, this confusion arises from overlooking the distinct life cycles of different plant groups. Angiosperms, as seed-producing plants, have evolved a more complex reproductive strategy. Their haploid spores are not free-living, unlike those of ferns or mosses, but are instead nurtured within the parent plant’s tissues. This adaptation allows angiosperms to thrive in diverse environments, from arid deserts to tropical rainforests, by ensuring successful fertilization and seed development.

Practical implications of this process are evident in agriculture and horticulture. For instance, understanding pollen viability (the health of male spores) is crucial for crop breeding and hybridization. Techniques like pollen staining or germination tests can assess haploid spore quality, directly impacting seed production. Similarly, in seedless fruit cultivation, such as bananas or certain citrus varieties, manipulating the female gametophyte (derived from haploid spores) is essential. This knowledge bridges the gap between theoretical botany and applied plant science, highlighting the importance of spore formation in angiosperm success.

In conclusion, angiosperms produce haploid spores through meiosis, a critical step in their life cycle that distinguishes them from other plant groups. This process is not only a biological marvel but also a practical cornerstone in plant breeding and agriculture. By clarifying the misconception about diploid spores, we gain a deeper appreciation for the evolutionary sophistication of flowering plants and their dominance in terrestrial ecosystems. Whether in a classroom, a laboratory, or a field, understanding spore formation in angiosperms is indispensable for anyone studying or working with plants.

Do HEPA Filters Effectively Remove Mold Spores from Indoor Air?

You may want to see also

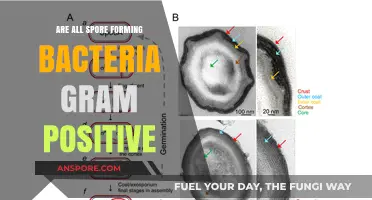

Life Cycle Stages: Alternation of generations includes diploid sporophyte and haploid gametophyte phases

Angiosperms, or flowering plants, exhibit a fascinating life cycle known as alternation of generations, which involves both diploid and haploid phases. This cycle is a cornerstone of their reproductive strategy, ensuring genetic diversity and adaptability. The diploid sporophyte phase, which is the dominant and visible part of the plant (think of the stems, leaves, and flowers), produces spores through meiosis. These spores are not diploid but haploid, marking the transition to the gametophyte phase. This alternation is a delicate balance, crucial for the plant’s survival and evolution.

The haploid gametophyte phase in angiosperms is significantly reduced compared to other plant groups, such as ferns or mosses. In angiosperms, the male gametophyte is the pollen grain, consisting of just a few cells, while the female gametophyte is the embryo sac within the ovule. Despite their simplicity, these structures play a pivotal role in sexual reproduction. Pollination brings the male gametophyte to the female, where fertilization occurs, restoring the diploid state and initiating the next sporophyte generation. This reduction in the gametophyte phase is an evolutionary adaptation that allows angiosperms to allocate more resources to growth and seed production.

Understanding the alternation of generations in angiosperms has practical implications for horticulture and agriculture. For instance, knowing that the sporophyte phase is diploid helps breeders predict how traits will be inherited. Techniques like grafting or hybridization rely on manipulating the sporophyte’s genetic material. Conversely, the haploid nature of the gametophyte phase is exploited in techniques like haploid induction, where plants are bred from pollen grains to accelerate the development of homozygous lines. This knowledge is invaluable for improving crop yields and creating disease-resistant varieties.

A comparative analysis reveals that while angiosperms share the alternation of generations with other plants, their unique reduction of the gametophyte phase sets them apart. This adaptation has contributed to their dominance in terrestrial ecosystems. For example, ferns have free-living gametophytes that require moisture for survival, limiting their distribution. In contrast, angiosperms’ compact gametophytes enable them to thrive in diverse environments, from arid deserts to lush rainforests. This evolutionary innovation underscores the efficiency and resilience of angiosperms.

In conclusion, the alternation of generations in angiosperms is a dynamic process that seamlessly integrates diploid sporophyte and haploid gametophyte phases. This cycle not only ensures genetic diversity but also supports the plant’s adaptability and reproductive success. By studying these phases, scientists and practitioners can harness their potential for agricultural advancements and ecological conservation. Whether you’re a botanist, farmer, or gardening enthusiast, appreciating this life cycle deepens your understanding of the natural world and its intricate mechanisms.

Understanding the Meaning and Usage of 'Spor' in Language and Culture

You may want to see also

Pollen and Embryo Sac: Pollen grains and embryo sacs are haploid, developing from spores

In angiosperms, the life cycle alternates between diploid (2n) and haploid (n) phases, a process known as alternation of generations. Pollen grains and embryo sacs, both critical to angiosperm reproduction, are haploid structures that develop from spores. This haploid state is essential for genetic diversity and the success of double fertilization, a unique feature of angiosperms. Understanding this distinction clarifies why angiosperm spores themselves are not diploid but give rise to haploid structures.

Pollen grains, produced in the anthers of flowers, are male gametophytes that develop from microspores via meiosis. Each microspore undergoes mitosis to form a mature pollen grain containing two haploid cells: a tube cell and a generative cell. This haploid nature ensures that upon fertilization, the resulting zygote is diploid, maintaining the species' chromosomal balance. Similarly, the embryo sac, or female gametophyte, develops from a megaspore within the ovule. Through meiosis and subsequent mitotic divisions, the megaspore forms a seven-celled, eight-nucleate structure, including one egg cell and two central cell nuclei, all haploid.

The haploid state of pollen grains and embryo sacs is a strategic adaptation in angiosperms. It allows for genetic recombination during meiosis, increasing diversity, while the fusion of haploid gametes during fertilization restores the diploid condition. This system contrasts with diploid spores in some non-vascular plants, where spores directly develop into gametophytes without reducing chromosome number. In angiosperms, the reduction to haploid occurs earlier, ensuring that only gametes, not spores, are diploid.

Practical implications of this haploid development are seen in plant breeding and agriculture. For instance, hybrid seed production relies on the haploid nature of pollen grains, enabling cross-pollination between distinct varieties. Breeders can manipulate pollen transfer to create hybrids with desirable traits, such as disease resistance or higher yield. Similarly, understanding the haploid embryo sac aids in embryo rescue techniques, where immature embryos are excised and grown in vitro, bypassing seed development barriers.

In summary, pollen grains and embryo sacs in angiosperms are haploid structures derived from spores, not diploid spores themselves. This distinction is fundamental to their reproductive strategy, ensuring genetic diversity and successful fertilization. By focusing on these haploid stages, researchers and breeders can harness angiosperm biology for advancements in agriculture and plant science.

Are Shroom Spores Illegal? Exploring the Legal Gray Area

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$12.32 $24.99

$17.99

$14.99 $19.99

Double Fertilization: Unique process in angiosperms, involving diploid endosperm and embryo formation

Angiosperms, or flowering plants, stand out in the plant kingdom due to their unique reproductive process known as double fertilization. This mechanism ensures the formation of both a diploid embryo and a triploid endosperm, setting the stage for successful seed development. Unlike other plants, where a single fertilization event suffices, angiosperms employ a dual approach, maximizing efficiency and resource allocation for the next generation.

To understand double fertilization, consider the journey of pollen grains from the anther to the stigma. Upon germination, a pollen tube grows, delivering two sperm cells to the ovule. The first sperm fertilizes the egg cell, resulting in a diploid zygote—the future embryo. Simultaneously, the second sperm fuses with the central cell, a diploid structure within the ovule, forming a triploid nucleus that develops into the endosperm. This nutrient-rich tissue serves as the embryo’s food source during seedling growth, a critical adaptation for angiosperms’ success in diverse environments.

From a practical standpoint, double fertilization highlights the precision of angiosperm reproduction. For gardeners or botanists, understanding this process can inform seed-saving techniques or hybridization efforts. For instance, knowing that endosperm viability is crucial for seed germination, one might focus on optimizing conditions for pollen transfer and ovule health. Additionally, the triploid nature of the endosperm explains why certain angiosperm hybrids fail to produce viable seeds—a phenomenon known as hybrid breakdown—due to chromosomal imbalances.

Comparatively, this process contrasts sharply with spore-producing plants like ferns or mosses, where spores are haploid and develop into gametophytes. Angiosperms bypass this intermediate stage, directly forming diploid embryos and triploid endosperm, streamlining their life cycle. This efficiency likely contributed to their dominance in terrestrial ecosystems, as it allows for rapid reproduction and adaptation to changing conditions.

In conclusion, double fertilization is not merely a biological curiosity but a cornerstone of angiosperm evolution. Its ability to produce both a diploid embryo and a triploid endosperm in a single reproductive event underscores the sophistication of flowering plants. Whether you’re a botanist, gardener, or simply curious about plant biology, appreciating this process offers deeper insights into the natural world and practical applications for plant cultivation and conservation.

Unveiling the Truth: Are Spore Storms Real or Myth?

You may want to see also

Sporophyte Dominance: Diploid sporophyte phase is dominant in angiosperms, unlike ferns or mosses

Angiosperms, or flowering plants, exhibit a striking feature in their life cycle: the diploid sporophyte phase is the dominant and long-lasting stage. This contrasts sharply with ferns and mosses, where the gametophyte phase holds greater prominence. In angiosperms, the sporophyte—the plant we typically see, complete with roots, stems, leaves, and flowers—is the primary phase, persisting for years or even centuries. The gametophyte, on the other hand, is reduced to a microscopic, short-lived structure within the flower’s reproductive organs. This dominance of the diploid sporophyte is a key evolutionary adaptation, allowing angiosperms to invest heavily in growth, resource acquisition, and reproduction, which contributes to their success in diverse ecosystems.

To understand this dominance, consider the life cycle stages. In angiosperms, spores produced by meiosis are diploid and develop directly into the sporophyte. This phase is not only longer but also more complex, featuring specialized tissues for water and nutrient transport, photosynthesis, and reproduction. In contrast, ferns and mosses have a haploid gametophyte phase that is free-living and photosynthetic, often lasting longer than their sporophyte counterparts. For example, a fern’s gametophyte is a small, heart-shaped structure that lives independently, while its sporophyte (the fern we recognize) depends on it for initial growth. Angiosperms reverse this dynamic, with the sporophyte nurturing the gametophyte, ensuring its survival and reproductive success.

This sporophyte dominance has practical implications for horticulture and agriculture. Gardeners and farmers focus on the diploid sporophyte phase, manipulating its growth through pruning, grafting, and fertilization to enhance yield and aesthetics. For instance, apple trees (angiosperms) are pruned to direct energy into fruit production rather than unnecessary foliage. In contrast, cultivating mosses or ferns often involves nurturing the gametophyte, which requires specific moisture and light conditions. Understanding this difference allows for tailored care strategies, ensuring the health and productivity of each plant type.

From an evolutionary perspective, sporophyte dominance in angiosperms reflects a shift toward greater efficiency in resource allocation. By prioritizing the diploid phase, angiosperms can develop robust vascular systems, enabling them to colonize a wide range of habitats, from arid deserts to dense forests. This adaptability is further enhanced by their flowering mechanism, which facilitates cross-pollination and genetic diversity. Ferns and mosses, with their gametophyte-centric life cycles, are more constrained in their growth and reproduction, limiting their ecological niches. Thus, sporophyte dominance is not just a structural feature but a strategic advantage that underpins angiosperms’ global prevalence.

In summary, the diploid sporophyte phase’s dominance in angiosperms is a defining trait that sets them apart from ferns and mosses. This dominance enables angiosperms to thrive through efficient resource use, complex growth patterns, and reproductive versatility. Whether in a garden, a farm, or the wild, this characteristic shapes how we interact with and care for these plants. By recognizing and leveraging sporophyte dominance, we can better appreciate the unique biology of angiosperms and optimize their cultivation for various purposes.

The Last of Us: Unveiling the Truth About Spores in the Show

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, angiosperm spores are typically haploid, produced by meiosis from a diploid sporophyte generation.

Angiosperms do not produce diploid spores; instead, they produce haploid spores that develop into gametophytes.

The spores in angiosperms are haploid (n), as they are formed by the reduction division (meiosis) of diploid cells.

Like other vascular plants, angiosperms produce haploid spores, not diploid spores, as part of their alternation of generations life cycle.