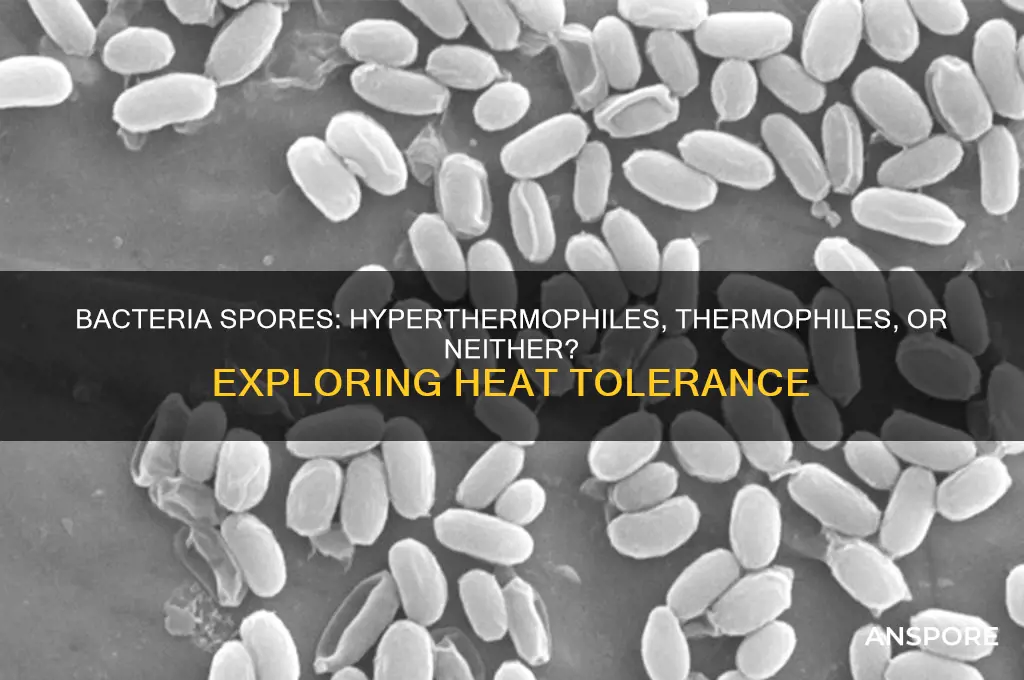

Bacteria spores, particularly those from species like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, are renowned for their remarkable resistance to extreme environmental conditions, including heat. However, when discussing whether these spores are hyperthermophiles or thermophiles, it’s essential to clarify the distinctions. Thermophiles are organisms that thrive at temperatures between 45°C and 80°C, while hyperthermophiles can survive and grow at temperatures above 80°C, often up to 110°C. Bacteria spores themselves are not inherently thermophiles or hyperthermophiles; rather, they are dormant, highly resistant structures that can withstand extreme temperatures, including those associated with thermophilic and hyperthermophilic environments. The classification of the bacteria producing these spores determines whether they are considered thermophiles or hyperthermophiles. For instance, spores from thermophilic bacteria like *Thermus aquaticus* can survive high temperatures, but the spores themselves are not active organisms; they are survival mechanisms. Thus, the focus should be on the bacterial species producing the spores rather than the spores themselves when categorizing them in relation to temperature preferences.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Optimal Growth Temperature | Thermophiles: 50-80°C Hyperthermophiles: 80-110°C |

| Survival Temperature Range | Thermophiles: Up to 80°C Hyperthermophiles: Up to 110°C or higher |

| Sporulation | Some thermophiles and hyperthermophiles form spores as a survival mechanism in extreme conditions. Spores are not exclusive to either group. |

| Examples | Thermophiles: Thermus aquaticus, Bacillus stearothermophilus Hyperthermophiles: Pyrolobus fumarii, Methanopyrus kandleri |

| Habitat | Thermophiles: Hot springs, hydrothermal vents, compost piles Hyperthermophiles: Deep-sea hydrothermal vents, geothermal areas |

| Cellular Adaptations | Both have heat-stable proteins, modified membranes, and DNA repair mechanisms. Hyperthermophiles often have more extreme adaptations due to higher temperatures. |

| Metabolism | Thermophiles: Diverse metabolic pathways Hyperthermophiles: Often rely on chemolithotrophic or anaerobic metabolism |

| Spore Resistance | Spores of both groups are highly resistant to heat, desiccation, and chemicals, but hyperthermophilic spores may withstand even more extreme conditions. |

| Classification | Thermophiles and hyperthermophiles are classified based on their optimal growth temperatures, not their ability to form spores. |

| Relevance to Industry | Thermophiles: Used in PCR (e.g., Taq polymerase) Hyperthermophiles: Studied for extremophile biology and potential biotechnological applications |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Bacterial spore heat resistance mechanisms

Bacterial spores are renowned for their extraordinary heat resistance, a trait that sets them apart from vegetative cells. This resilience is not merely a passive feature but an active, multi-layered defense mechanism honed through evolution. At the core of this resistance lies the spore’s unique structure, which includes a thick, multi-layered coat composed of proteins and peptidoglycan. These layers act as a physical barrier, reducing the penetration of heat and other stressors. Additionally, the spore’s low water content and the presence of dipicolinic acid (DPA) in the core play critical roles. DPA, a calcium-chelating molecule, stabilizes the spore’s DNA and proteins, preventing denaturation at high temperatures. This combination of structural and chemical adaptations allows spores to withstand temperatures that would destroy most other life forms.

One of the most fascinating aspects of spore heat resistance is the role of small acid-soluble proteins (SASPs). These proteins bind to DNA, forming a protective alpha-helical structure that shields the genetic material from thermal damage. SASPs also help maintain DNA in a condensed, stable state, further enhancing resistance. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* spores contain high levels of SASPs, contributing to their ability to survive pasteurization temperatures (60–70°C). In contrast, spores lacking SASPs or with reduced DPA levels exhibit significantly lower heat tolerance, underscoring the importance of these molecules in the resistance mechanism.

Practical applications of spore heat resistance are evident in food preservation and sterilization processes. Autoclaves, which operate at 121°C for 15–20 minutes, are designed to kill spores by overcoming their defenses. However, some spores, like those of *Geobacillus stearothermophilus*, can survive even these extreme conditions, necessitating the use of biological indicators to ensure sterilization efficacy. In the food industry, thermal processing parameters (e.g., 100°C for 3 minutes for canned foods) are carefully calibrated to target spore inactivation, as spores of *Clostridium botulinum* pose a significant risk if they survive. Understanding these mechanisms allows for the development of more effective heat treatments tailored to specific spore types.

A comparative analysis reveals that while bacterial spores are not hyperthermophiles (organisms thriving at temperatures above 80°C), they exhibit thermophile-like resistance in their dormant state. Hyperthermophiles, such as *Thermococcus* species, actively grow at high temperatures due to thermostable enzymes, whereas spores remain metabolically inactive until conditions become favorable. This distinction highlights that spore heat resistance is a survival strategy rather than an adaptation for growth in extreme environments. By studying these mechanisms, scientists can engineer more heat-resistant enzymes or develop targeted antimicrobial strategies, bridging the gap between fundamental biology and applied biotechnology.

In summary, bacterial spore heat resistance is a complex, multi-faceted phenomenon rooted in structural, chemical, and molecular adaptations. From the protective coat to the stabilizing role of DPA and SASPs, each component contributes to the spore’s ability to endure extreme temperatures. Practical implications span industries, from ensuring food safety to validating sterilization processes. While spores are not hyperthermophiles, their thermophile-like resistance in dormancy offers valuable insights into biological survival strategies. This knowledge not only deepens our understanding of microbial life but also inspires innovative solutions to real-world challenges.

Mastering Mushroom Cultivation: A Guide to Growing Shroom Spores

You may want to see also

Hyperthermophile vs. thermophile classification criteria

Bacteria and archaea that thrive in extreme temperatures are classified as either thermophiles or hyperthermophiles, but the distinction isn't always clear-cut. The primary criterion lies in their optimal growth temperatures: thermophiles flourish between 50°C and 80°C, while hyperthermophiles require temperatures above 80°C, often peaking around 100°C. For instance, *Thermus aquaticus*, a well-known thermophile, grows optimally at 70°C, whereas *Pyrolobus fumarii*, a hyperthermophile, thrives at 106°C. This temperature threshold is critical for classification, as it reflects the organism’s evolutionary adaptations to stabilize proteins and membranes under extreme heat.

Beyond optimal growth temperatures, the classification also hinges on the organism’s ability to survive and reproduce at temperature extremes. Thermophiles typically cannot grow above 80°C, whereas hyperthermophiles not only survive but also reproduce at temperatures exceeding this limit. For example, spores of *Bacillus* species, which are thermophiles, can withstand high temperatures but do not qualify as hyperthermophiles because their optimal growth occurs below 80°C. In contrast, hyperthermophilic archaea like *Methanopyrus kandleri* can grow at 122°C, showcasing a remarkable tolerance that redefines the boundaries of life.

Practical classification often involves laboratory tests to determine temperature ranges for growth and survival. Scientists use gradient cultures or thermal tolerance assays to pinpoint the upper and lower limits of an organism’s viability. For instance, a hyperthermophile might exhibit no growth below 80°C but robust growth at 95°C, whereas a thermophile would show peak activity at 65°C and no growth above 80°C. These experiments are crucial for distinguishing between the two groups, especially in mixed microbial communities from hydrothermal vents or hot springs.

The molecular basis for classification lies in the structural and functional adaptations of biomolecules. Hyperthermophiles possess proteins and membranes stabilized by increased ionic bonding, shorter peptide chains, and unique lipids resistant to thermal denaturation. Thermophiles, while also adapted to heat, lack these extreme modifications. For example, the DNA polymerase from *Thermus aquaticus* (Taq polymerase) is heat-stable but not to the extent of enzymes from hyperthermophiles, which can function at temperatures exceeding 100°C. These molecular differences underscore the evolutionary divergence between the two groups.

In summary, the classification of thermophiles and hyperthermophiles is rooted in precise temperature thresholds, survival capabilities, and molecular adaptations. While thermophiles thrive below 80°C, hyperthermophiles push the limits of life above this boundary. Understanding these criteria not only clarifies taxonomic distinctions but also highlights the remarkable diversity of life in Earth’s most extreme environments. Whether studying spores or entire organisms, these classifications provide a framework for exploring the boundaries of thermal tolerance in the microbial world.

Exploring Legal Ways to Obtain Psychedelic Mushroom Spores Safely

You may want to see also

Temperature ranges for spore survival

Bacterial spores exhibit remarkable resilience, particularly in their ability to withstand extreme temperatures. While some spores thrive in high-heat environments, others survive prolonged exposure to cold. Understanding these temperature ranges is crucial for industries like food preservation, sterilization, and astrobiology.

Analyzing Survival Thresholds:

Bacterial spores can endure temperatures as low as -20°C (-4°F) for extended periods, making them a challenge in frozen food storage. At the upper end, spores of thermophiles like *Geobacillus stearothermophilus* survive brief exposure to 100°C (212°F), while hyperthermophilic spores, such as those from *Thermococcus* species, can persist at temperatures exceeding 121°C (250°F), the standard autoclave sterilization temperature. However, prolonged exposure to these extremes reduces viability, with survival rates dropping exponentially beyond 15 minutes at 121°C.

Practical Applications and Cautions:

In food processing, knowing spore survival ranges is vital. For instance, *Clostridium botulinum* spores require temperatures above 121°C for 3 minutes to ensure destruction. In contrast, mesophilic spore-formers like *Bacillus cereus* are inactivated at 72°C (162°F) for 15 seconds. Caution is advised when relying on refrigeration alone, as spores remain dormant but viable at 4°C (39°F), posing risks during food thawing or improper cooking.

Comparative Resilience:

Hyperthermophilic spores outcompete thermophiles in extreme heat tolerance, but both surpass mesophiles in survival versatility. For example, *Deinococcus radiodurans* spores withstand not only high temperatures but also radiation, showcasing overlapping extremophile traits. This comparison highlights the evolutionary adaptations of spores to diverse environments, from deep-sea hydrothermal vents to arid deserts.

Takeaway for Sterilization and Preservation:

To ensure spore inactivation, precise temperature-time combinations are essential. Autoclaving at 134°C (273°F) for 3–5 minutes targets hyperthermophilic spores, while pasteurization at 72°C for 15 seconds suffices for most mesophilic contaminants. For cold storage, combining low temperatures with controlled humidity reduces spore longevity, though complete eradication remains challenging without heat treatment.

This knowledge empowers industries to tailor sterilization protocols, ensuring safety while minimizing energy use and resource waste.

Can Bacteria Form Spores? Unveiling Microbial Survival Strategies

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spore-forming bacteria in extreme environments

Bacterial spores are renowned for their resilience, capable of withstanding extreme conditions that would annihilate most life forms. Among these conditions, temperature extremes—both scorching heat and freezing cold—pose significant challenges. Spore-forming bacteria, such as those in the genus *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, have evolved to survive in environments where temperatures can fluctuate dramatically. But are these spores hyperthermophiles, thriving in temperatures above 80°C, or thermophiles, which prefer temperatures between 50°C and 80°C? The answer lies in understanding the spore’s dormant state and its metabolic inactivity, which distinguishes it from actively growing cells that define thermophilic or hyperthermophilic behavior.

Consider the example of *Bacillus subtilis*, a spore-forming bacterium commonly found in soil. Its spores can endure temperatures up to 121°C for 20 minutes, a feat achieved through a combination of structural robustness and biochemical adaptations. The spore’s outer coat, composed of keratin-like proteins, acts as a thermal barrier, while the core’s low water content minimizes heat-induced damage. However, this survival mechanism does not classify the spore itself as a hyperthermophile or thermophile, as these terms apply to actively metabolizing organisms. Instead, the spore’s ability to persist in extreme heat is a passive survival strategy, not an active preference for high temperatures.

To understand the distinction, compare spore-forming bacteria with true thermophiles like *Thermus aquaticus* or hyperthermophiles like *Pyrococcus furiosus*. These organisms maintain metabolic activity at high temperatures, synthesizing enzymes optimized for stability under heat. In contrast, bacterial spores remain metabolically dormant until conditions become favorable for germination. This dormancy allows them to inhabit environments ranging from geothermal springs to polar ice caps, where temperatures can swing from near-boiling to sub-zero. For instance, spores of *Bacillus* species have been isolated from hot springs in Yellowstone National Park and from permafrost in the Arctic, showcasing their adaptability to both thermophilic and psychrophilic (cold-loving) niches.

Practical applications of spore resilience are vast. In the food industry, spores of *Clostridium botulinum* pose a significant challenge, as they can survive pasteurization temperatures (typically 72°C for 15 seconds) and germinate under favorable conditions, producing deadly toxins. To combat this, food manufacturers employ sterilization techniques like autoclaving (121°C for 15–20 minutes) to ensure spore inactivation. Conversely, in biotechnology, spores’ heat resistance is harnessed for enzyme production, such as the use of *Bacillus* amylases in starch processing, which remain stable at elevated temperatures.

In conclusion, while spore-forming bacteria can survive in environments frequented by thermophiles and hyperthermophiles, their spores are not classified as such. Their resilience is a testament to evolutionary ingenuity, enabling them to persist in extreme conditions without active metabolic engagement. This distinction is crucial for both scientific understanding and practical applications, from food safety to industrial processes. By studying these spores, we gain insights into life’s limits and the strategies organisms employ to transcend them.

Exploring Nature's Strategies: How Spores Travel and Disperse Effectively

You may want to see also

Role of spores in thermal adaptation

Bacterial spores are renowned for their resilience, capable of withstanding extreme conditions that would annihilate their vegetative counterparts. Among these conditions, temperature extremes—both high and low—pose significant challenges. The role of spores in thermal adaptation hinges on their ability to enter a dormant state, effectively pausing metabolic activity until conditions become favorable. This mechanism is particularly crucial for thermophiles and hyperthermophiles, organisms that thrive in high-temperature environments. While spores themselves are not classified as thermophiles or hyperthermophiles, they serve as a survival strategy for bacteria that inhabit these extreme niches.

Consider the example of *Geobacillus stearothermophilus*, a thermophilic bacterium whose spores can survive temperatures up to 120°C for extended periods. These spores are often used as biological indicators in sterilization processes, such as autoclaving, to ensure equipment reaches lethal temperatures. The spore’s heat resistance is attributed to its robust outer layers, including a thick protein coat and a cortex rich in dipicolinic acid (DPA), which stabilizes the spore’s structure under heat stress. This adaptation allows the bacterium to persist in hot environments, such as geothermal springs or industrial processes, where temperatures routinely exceed 50°C.

From a practical standpoint, understanding spore thermal adaptation is critical for industries like food preservation and medical sterilization. For instance, canned food manufacturers must apply specific time-temperature combinations (e.g., 121°C for 3 minutes) to ensure spore destruction, particularly from mesophilic bacteria like *Clostridium botulinum*. In contrast, hyperthermophilic spores, though less common, pose challenges in extreme environments like deep-sea hydrothermal vents, where temperatures can exceed 100°C. Here, spores act as a reservoir, enabling bacterial populations to rebound once temperatures fluctuate.

A comparative analysis reveals that while thermophiles and hyperthermophiles actively metabolize at high temperatures, their spores are passive survival structures. The distinction lies in the spore’s ability to endure temperatures beyond the organism’s growth range, serving as a bridge between hostile and habitable conditions. For example, *Thermococcus gammatolerans*, a hyperthermophile thriving at 85°C, relies on spores to survive temperature spikes that would otherwise be lethal. This highlights the spore’s role as a thermal buffer, decoupling survival from active metabolism.

In conclusion, spores are not thermophiles or hyperthermophiles themselves but are indispensable tools for thermal adaptation in these bacteria. Their ability to withstand extreme temperatures ensures the persistence of bacterial populations in fluctuating environments. For researchers and practitioners, this knowledge underscores the importance of targeting spores in sterilization protocols and informs strategies for studying extremophiles. By focusing on spore biology, we gain insights into the limits of life and the mechanisms that enable survival in Earth’s most inhospitable habitats.

Understanding Spore Ploidy: Haploid or Diploid in Fungi and Plants

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Bacteria spores themselves are not classified as hyperthermophiles or thermophiles. These terms describe the temperature ranges at which certain bacteria or archaea can grow and thrive. Spores are dormant, resilient forms that some bacteria produce to survive harsh conditions, but they do not actively metabolize or grow until they germinate.

Yes, some bacteria that form spores, such as certain species in the genus *Bacillus* or *Thermus*, can be thermophiles or hyperthermophiles. These bacteria can survive and grow at high temperatures, and their spores are adapted to withstand extreme conditions.

Some hyperthermophiles and thermophiles, particularly among bacteria, can produce spores. For example, *Thermus* species are thermophiles known to form spores. However, many archaeal hyperthermophiles do not produce spores, as they rely on other mechanisms to survive extreme environments.